Download NATO’s broadcast-quality video content free of charge

Log in

NATO MULTIMEDIA ACCOUNT

Access NATO’s broadcast-quality video content free of charge

Check your inbox and enter verification code

You have successfully created your account

From now on you can download videos from our website

Subscribe to our newsletter

If you would also like to subscribe to the newsletter and receive our latest updates, click on the button below.

Enter the email address you registered with and we will send you a code to reset your password.

Didn't receive a code? Send new Code

The password must be at least 12 characters long, no spaces, include upper/lowercase letters, numbers and symbols.

Your password has been updated

Click the button to return to the page you were on and log in with your new password.

Collective defence and Article 5

Updated: 12 November 2025

Collective defence is NATO’s most fundamental principle. Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty states that an armed attack against one NATO member shall be considered an attack against them all. Since 1949, this unwavering pledge has bound together a group of like-minded countries from Europe and North America, which have committed themselves to protecting each other in a spirit of solidarity.

- Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty states that an armed attack against one NATO member shall be considered an attack against all members, and triggers an obligation for each member to come to its assistance.

- This assistance may or may not involve the use of armed force, and can include any action that Allies deem necessary to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.

- NATO’s Article 5 is consistent with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, which recognises that a state that is the victim of an armed attack has the inherent right to individual or collective self-defence, and may request others to come to its assistance. Within the NATO context, Article 5 translates this right of self-defence into a mutual assistance obligation.

- NATO invoked Article 5 for the first and only time in its history after the 9/11 terrorist attacks against the United States in 2001.

- While Article 5 itself has been applied only once, it underpins all of NATO’s broader activities in the field of deterrence and defence, including the regular conduct of military exercises and the deployment of NATO’s standing military forces.

- NATO takes a 360-degree approach to collective defence, protecting against all threats from all directions.

The origins of Article 5

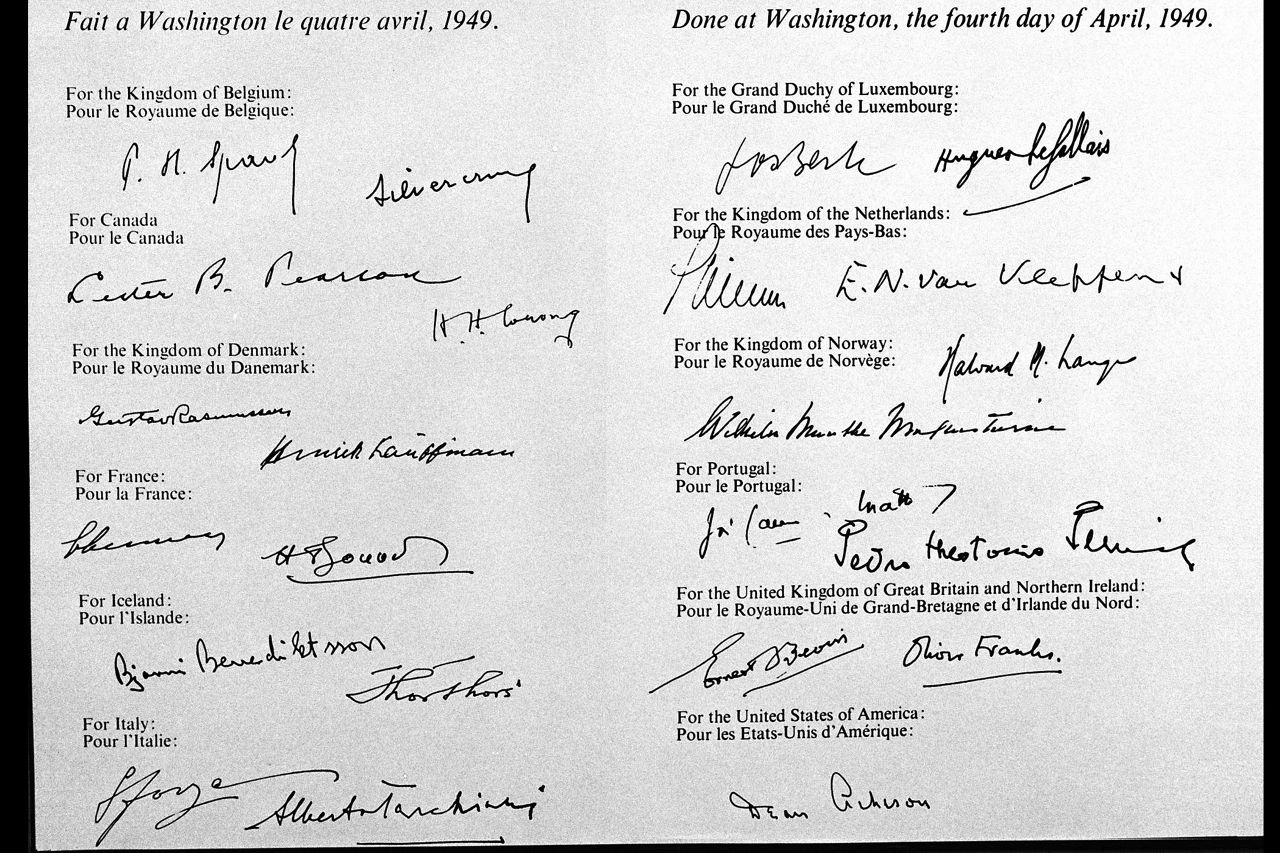

On 4 April 1949, 12 countries from Europe and North America came together in Washington, D.C. to sign the North Atlantic Treaty. NATO’s founding treaty is not long – only 14 articles, just over 1,000 words – and its core purpose is clear and simple: a joint pledge by each country to assist the others if they come under attack.

This was particularly urgent in the early days of the Cold War. The Soviet Union had drawn the Iron Curtain across Europe, dominating its neighbours in Central and Eastern Europe and threatening to extend its control further west – unless it met with concerted resistance.

The 12 founding NATO Allies, many of them still rebuilding their economies and militaries after the devastation of the Second World War, agreed that uniting their strength and committing to protect each other was key to deterring the Soviet threat. Article 5 of the Washington Treaty was the clearest articulation of that promise, and it has remained the bedrock of the transatlantic bond at the heart of NATO ever since.

The North Atlantic Treaty was drafted four years after the adoption of the United Nations Charter in 1945. The Treaty makes explicit reference to the Charter no less than five times throughout its short text, including in its first sentence. Article 5 specifically notes that NATO Allies can take collective defence actions consistent with their rights under Article 51 of the UN Charter, which recognises that a state that sustains an armed attack has the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence, and may request others to come to its assistance. This right serves as a legal basis for taking internationally lawful military action in defence of the attacked.

This right to collective self-defence also permits states to conclude mutual defence arrangements on a bilateral or multilateral basis, in which they agree to come to each other’s assistance in case of a future armed attack. Such arrangements can exert an important deterrent effect against potential aggressors, as the example of NATO has illustrated for more than 75 years. While numerous mutual assistance obligations exist (for instance, the European Union and the Organization of American States also have collective defence treaty clauses), the degree of military coordination within NATO, and the Alliance’s collective military strength, render NATO’s Article 5 a uniquely powerful tool.

Article 5 states that if a NATO Ally sustains an armed attack, every other member of the Alliance will consider this as an armed attack against all members, and will take the actions it deems necessary to assist the attacked Ally.

Article 5

“The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.

Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall immediately be reported to the Security Council. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security.”

What counts as an ‘armed attack’ under Article 5?

Article 5 applies only in case of an ‘armed attack’. An obvious example would involve an invasion by one state of the territory of another state. This type of threat continues to be a serious concern, and constitutes a major focus of NATO’s efforts to maintain and develop its capacity to defend all Allies. However, what amounts to an ‘armed attack’ in the context of Article 5 must be assessed on a case-by-case basis and is not limited to traditional notions of overt military strikes by a state actor. For example, NATO invoked Article 5 in response to Al Qaeda’s terrorist attacks against the United States on 11 September 2001 (see more details below). Events that lack an international element, such as purely domestic acts of terrorism, do not trigger Article 5 (though NATO Allies can and often do offer assistance in such cases). At recent NATO summits, Allied Leaders have clarified that Article 5 may apply to attacks to, from or within space, and that significant cyber attacks and other hybrid attacks may be considered as amounting to an ‘armed attack’.

Article 6 of the North Atlantic Treaty imposes geographic limitations on the scope of NATO’s mutual assistance obligation, primarily limiting it to the North Atlantic area north of the Tropic of Cancer.

How is Article 5 triggered?

The North Atlantic Treaty does not prescribe a specific procedure to trigger Allies’ mutual assistance obligation under Article 5.

The obligation to assist an Ally “forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties” arises when two conditions are met:

- an Ally has sustained an ‘armed attack’ as described above (the assessment of which is to be conducted in good faith by all Allies, whether individually or collectively), and

- the attacked Ally requests or consents to collective action under Article 5. An attacked Ally may choose not to seek assistance under Article 5, and instead address the situation through other avenues.

NATO Allies meet regularly in the North Atlantic Council, NATO’s principal political decision-making body, to discuss security issues of concern to the Alliance. If a NATO Ally experiences an armed attack, a meeting of the Council will be convened immediately to discuss whether this attack is regarded as an action covered by Article 5. If it is determined that the two conditions above have been met, NATO Allies may issue a political statement invoking or declaring that they are taking collective defence actions under Article 5.

It is also the case that any Ally can communicate a request for assistance to its fellow NATO Allies pursuant to Article 4 of the North Atlantic Treaty. Article 4 provides for consultations between Allies whenever, in the opinion of any of them, an Ally’s territorial integrity, political independence or security is threatened. It’s important to note, however, that Article 4 consultations are not a necessary precondition for action under Article 5. Nor do consultations under Article 4 imply the consideration of Article 5.

What happens when Article 5 is triggered?

When Article 5 is triggered, each Ally is obliged to assist the attacked Ally or Allies by taking “such action as it deems necessary” to respond to the situation. This is an individual obligation placed on each Ally, to be taken forward in consultation and coordination with other Allies.

In an Article 5 situation, NATO plays a vital role in this consultation and coordination process, providing a unified response in support of the attacked Ally. Through NATO, the attacked Ally can identify their security needs and receive offers of assistance, ensuring that actions taken by NATO and Allies are synchronised. For example, following the 9/11 attacks, NATO Allies agreed eight measures to support the United States (see the next section). Coordination through NATO does not limit Allies from taking unilateral or bilateral actions as well.

It is up to individual Allies to determine how they will implement the mutual assistance obligation, so long as their efforts can be regarded as consistent with what is necessary “to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.” Action pursuant to Article 5 may or may not involve the use of armed force.

Importantly, Article 11 of the Treaty acknowledges and accepts that there may be constitutional limitations that impact how individual Allies fulfil their obligation under Article 5 (the deployment of armed forces abroad may, for instance, be subject to prior parliamentary approval or consultation in some countries).

During the drafting of Article 5 in the late 1940s, there was consensus on the principle of mutual assistance, but differing views on how this commitment would be implemented in practice. The European participants wanted to ensure that the United States would automatically deploy its armed forces to defend their territory should one of the signatories come under attack; the United States did not want to make such a specific pledge, and this is reflected in the more flexible wording of Article 5, which obliges Allies to provide assistance but does not specify the type or degree of assistance that they choose to provide.

Actions under Article 5 following the 9/11 attacks

On 11 September 2001, the United States was struck by brutal terrorist attacks that killed and injured thousands of people. The Alliance’s response to 9/11 saw NATO engage actively in the fight against terrorism, launch its first operations outside the Euro-Atlantic area and begin a far-reaching transformation of its capabilities. Moreover, it led NATO to take action under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty for the first and (so far) only time in its history.

Showing solidarity

On 11 September 2001, the North Atlantic Council issued a statement condemning the attacks and expressing solidarity with the United States. On the evening of 12 September 2001, less than 24 hours after the attacks, Allies met in the North Atlantic Council. The Council agreed “that if it is determined that this attack was directed from abroad against the United States, it shall be regarded as an action covered by Article 5 of the Washington Treaty”. NATO Secretary General Lord Robertson subsequently informed the Secretary-General of the United Nations of the Alliance’s decision.

On 2 October 2001, once the Council had been briefed on the results of investigations into the 9/11 attacks, it determined that they were effectively regarded as an action covered by Article 5.

Taking action

In the following weeks, consultations among the Allies were held and collective action was decided by the Council. This was without prejudice to the United States’ right to carry out independent actions, consistent with the United Nations Charter.

On 4 October 2001, NATO agreed on a package of eight measures to support the United States:

- to enhance intelligence-sharing and cooperation, both bilaterally and in appropriate NATO bodies, relating to the threats posed by terrorism and the actions to be taken against it;

- to provide, individually or collectively, as appropriate and according to their capabilities, assistance to Allies and other countries which are or may be subject to increased terrorist threats as a result of their support for the campaign against terrorism;

- to take necessary measures to provide increased security for facilities of the United States and other Allies on their territory;

- to backfill selected Allied assets in NATO’s area of responsibility that are required to directly support operations against terrorism;

- to provide blanket overflight clearances for the United States and other Allies’ aircraft, in accordance with the necessary air traffic arrangements and national procedures, for military flights related to operations against terrorism;

- to provide access for the United States and other Allies to ports and airfields on the territory of NATO member countries for operations against terrorism, including for refuelling, in accordance with national procedures;

- that the Alliance is ready to deploy elements of its Standing Naval Forces to the Eastern Mediterranean in order to provide a NATO presence and demonstrate resolve;

- that the Alliance is similarly ready to deploy elements of its NATO Airborne Early Warning Force to support operations against terrorism.

On the request of the United States, the Alliance launched its first-ever anti-terror operation – Operation Eagle Assist – from 9 October 2001 to mid-May 2002. This operation consisted of seven NATO AWACS radar aircraft that helped patrol the skies over the United States; in total, 830 crew members from 13 NATO countries flew over 360 sorties. This was the first time that NATO military assets were deployed in support of an Article 5 operation.

On 26 October 2001, the Alliance launched its second counter-terrorism operation in response to the attacks on the United States, Operation Active Endeavour, which involved elements of NATO's Standing Naval Forces patrolling the Mediterranean Sea to detect and deter terrorist activity, including illegal trafficking. Initially an Article 5 operation, Active Endeavour benefitted from support from non-NATO countries from 2004 onwards. The operation ended in 2016.

Resilience and deterrence: the first line of collective defence

Collective defence is only effective if it is backed by strong, credible defence capabilities. As such, the mutual assistance obligation under Article 5 must be read together with Allies’ commitment to “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack”, as expressed in Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty. Cooperation between Allies under Article 3 creates the conditions for effective collective action under Article 5, should the need arise.

Furthermore, the two articles not only lay the groundwork for the effective implementation of the mutual assistance obligation, if an armed attack against an Ally were to take place. They also provide a powerful deterrent against potential aggressors, by helping to prevent an attack from occurring in the first place. By developing the resilience of their societies against armed attacks or other major shocks or disruptions (Article 3) and by pledging their mutual assistance in the event of an armed attack (Article 5), NATO Allies deter aggression and ensure they are prepared.

Although NATO Allies have only taken action under Article 5 once, they have coordinated deterrence measures throughout the Alliance’s history, preventing conflict by preparing for collective defence. Throughout the Cold War, Allies stationed troops across Europe and conducted large-scale military exercises to demonstrate their capabilities. More recently, since Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, and especially since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, NATO has increased the size and responsiveness of its high-readiness forces and bolstered its military presence along the Alliance’s eastern flank. This has included the deployment of multinational forward land forces to Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia; increased air policing by Allied fighter jets; and strengthened air and missile defence, among many other activities. The Alliance has also taken steps to address security challenges from the south, including from terrorism in all its forms and manifestations.

Learn more about specific measures that the Alliance has taken to deter aggression and ensure the ability to defend: Deterrence and defence, Strengthening NATO’s eastern flank