The Cold War

Science and innovation

Military inventions that we use every day

When you hear the words 'military inventions', you probably think of battle tanks, gigantic warships, supersonic fighter jets and explosives that shake the earth. But some of the most significant military inventions are much less flashy but just as important – things that we use every day in the civilian world.

Our militaries have one paramount duty: to keep us safe from any threat. Over the years, countless inventors from NATO countries have created new technologies, big and small, that contribute to that ultimate goal. The spill-over effects of this innovation are all around us, and have laid the foundations of our modern world.

NATO has supported science and innovation for more than 70 years. The Alliance not only provides direct funding to researchers, but also maintains networks that bring together thousands of scientists from around the world to collaborate and build on each other's work.

Military innovation in science and technology has helped to create some of the most iconic and essential items in our streets, offices and homes. Here are seven of the most interesting inventions pioneered and popularised by NATO militaries that are now common in everyday life…

1 - The internet

The Internet became a truly global network in the 1970s. Photo: Yuichiro Chino via Getty Images

The number one military invention that we use every day is how you're reading this right now: the Internet.

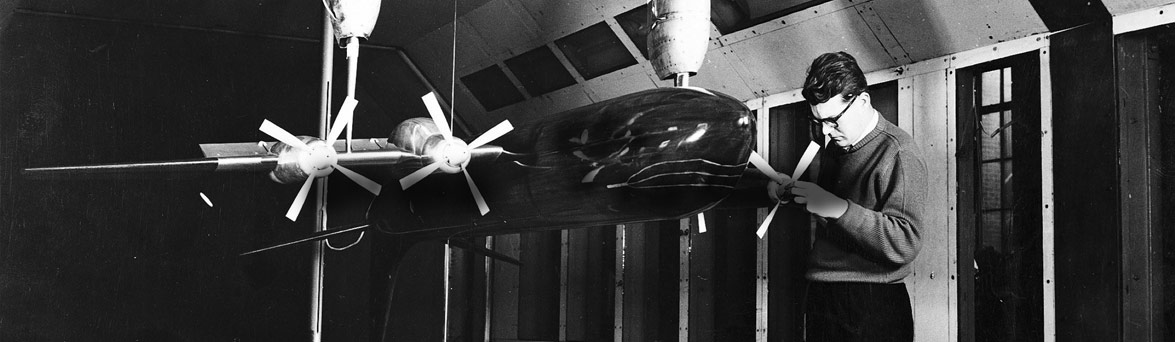

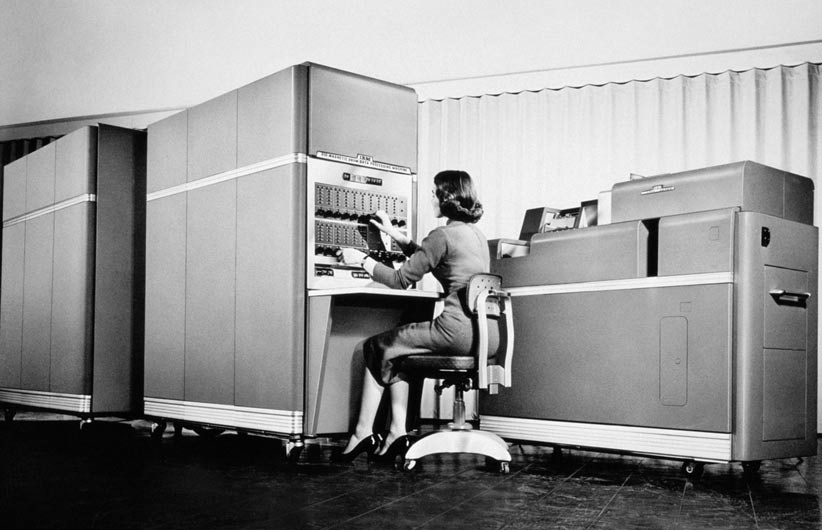

The Internet as we know it today started its life in 1969 as the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network, or ARPANET. Created by scientists working for the US Department of Defense, its initial purpose was to link universities, government agencies and defence contractors throughout the United States, enabling exchanges of information and shared computing power. Computers at that time were gigantic machines with strict limitations to the operations that they could perform. Connecting them together enabled them to perform increasingly complex calculations at a faster speed.

One of the key features of ARPANET was its wide horizontal dispersal into a 'distributed network' of multiple nodes. In the Cold War context, it was important to build an information-sharing and computational system without a central command hub that could become a juicy target for adversaries. The very name 'Internet' comes from this spread-out structure: groups of interlinked computers (networks) were connected together to form larger clusters (internetworks).

The first message communicated through ARPANET was sent from a computer at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) to Stanford University outside of San Francisco in 1969. A computer engineer at UCLA attempted to access the Stanford network by typing 'LOGIN' – although the system crashed and only transmitted 'LO' to the Stanford end. Later, the two networks were successfully bridged, and other US networks were eventually added to the mix.

Early computers were big enough to fill a room. Photo: Archive Holdings Inc. via Getty Images

In 1973, ARPANET was connected to the Royal Radar Establishment in Norway and University College London in the United Kingdom, creating a transatlantic link between NATO Allies. This was also when the term 'Internet' was born.

The following year, computer scientists Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf (sometimes called the Fathers of the Internet) created a new way of exchanging data between networks, called Transmission-Control Protocol, and later Internet Protocol (TCP/IP). This allowed computers in different networks to speak the same language, and led to ARPANET spreading even more quickly around the world throughout the 1970s and 1980s, laying the foundations for the modern Internet.

In 1991, Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web while working at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Switzerland. Although we use the words 'Internet' and 'World Wide Web' interchangeably, they are in fact different. The Internet is the infrastructure of interlinked computer networks; the World Wide Web is the collection of documents and files (web pages, images, videos, etc.) that we access through the Internet.

The creation of the World Wide Web as a user-friendly interface that can be easily navigated by anyone led to the mass popularisation of the Internet for the general public. No longer were these networks limited to universities, tech companies and militaries. The 1990s and 2000s saw the development of more and more websites, the beginning of e-commerce and web-based companies, and the rise of social media. By the 2020s, more than half of the global population (over 4.5 billion people) was connected to the Internet.

The Internet has reshaped our world more than any other invention on this list. It was truly a global venture, with scientists from NATO Allies on either side of the Atlantic contributing to its development. With every innovation, it has become more and more central to our lives, changing the ways we travel, work, entertain ourselves and keep ourselves safe. It started its life as a military invention, but now it's safe to say that it includes the entire scope of the human experience – from declassified military documents to cat memes.

2 - GPS satellite navigation

Be honest – when was the last time you took a trip, or even went around your hometown, without using an app to find your way? Global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) help us get from point A to point B using a constellation of satellites that was first set up by the US Department of Defense in the 1970s thanks to GPS (Global Positioning System) technology.

Photo: Oscar Wong via Getty Images

In 1978, the Department launched the first satellite in its Navigation System with Timing and Ranging (NAVSTAR). The system became fully operational in 1993, with 24 satellites orbiting the Earth at approximately 19,300 km up.

The NAVSTAR system was originally limited to the US military and selected allies. However, the US government decided to make GPS freely available to the whole world in 1983, after a tragic air incident. A Korean commercial airliner flying from New York to Seoul accidentally drifted from its intended route into prohibited Soviet airspace, where it was shot down by a Soviet fighter jet, killing everyone on board. This incident could have been avoided with more accurate navigation tools, and so GPS was released to the public and adopted in civilian aviation and many other fields.

An artist's illustration of a NAVSTAR satellite above Earth. Image: US Air Force/public domain

In the 21st century, GPS has become so universal that it's easy to forget that it's a free service provided and maintained by the US military. Other countries have also launched satellites and developed their own systems, including Russia's GLOSNASS, China's BeiDou and the European Union's Galileo, all of which share free navigational data with the public to some degree.

With more and more satellites and space junk in Earth's orbit, the potential for disruption to the various GNSS networks becomes greater every year. Nonetheless, GSP will continue to be crucial to our movements, economies and lives for the foreseeable future – whether we're tracking the course of a missile or watching the path of our pizza delivery.

This animation shows how signals between multiple GPS satellites determine the precise coordinates of a single point on the Earth's surface. Image: Wikimedia Commons/User: Paulsava

3 - MICROWAVE OVENS

Microwave cooking was accidentally discovered during the course of a totally unrelated project for a military contractor just after the Second World War.

A typical microwave oven. Photo: Bianca Dantas / EyeEm via Getty Images

Radar technology had grown by leaps and bounds throughout the war, and it continued to be crucial in the emerging Cold War, when NATO radar installations constantly scanned the skies for planes or missile threats from the Soviet Union. In 1946, a scientist named Percy Spencer was working on a magnetron (a device that produces the vibrating electromagnetic waves that make radar possible) to increase the power levels that could be used in radar sets. One day, midway through his experiments, he put his hand into his pocket and discovered that the peanut cluster candy bar he had been saving for lunch had melted.

Curious to experiment more, Spencer concentrated the magnetron's electromagnetic waves on a raw egg – and it exploded in his face, covering him with goo. Undeterred, Spencer brought in some kernels of corn and made the first-ever microwave popcorn, which he shared with his office mates.

It didn't take long for Spencer and his company to develop a commercial microwave oven. The first model, called a 'Randarange', was released on the market in 1947, only a year after Spencer's initial discovery. But the machine was gigantic, heavy and too expensive for the average family to buy: almost two metres tall, over 340 kg and USD 5,000 (in 1947!). It would take another 20 years for the technology to be miniaturised and made affordable enough for the average family. By the end of the 1960s, over a million microwave ovens were sold every year, becoming the household fixture that we know and love today.

4 - DUCT TAPE

What's stronger, more durable and more versatile than duct tape? A mother's determination.

Vesta Stoudt worked in a munitions factory during the Second World War while her sons served in the United States Navy. At the time, the standard practice for packing artillery shells was to seal a box with paper tape, with a little bit of tape left as a tab at the end that troops could pull to open the box, and then dip the whole thing in wax to make it waterproof.

But the paper tabs were so flimsy that they would often rip off without breaking through the wax or pulling off the rest of the tape. This posed a great danger to troops. If the tabs didn't work, it would waste precious time in the midst of combat, possibly meaning the difference between life and death.

Stoudt won the Chicago Tribune's War Worker Award for her idea in 1943. Photo from Octane Creative (reproduced from the Chicago Tribune).

Stoudt proposed that they replace the wax and paper tape with a new type of water-resistant, cloth-based tape instead. She raised the issue with her supervisors and with government inspectors when they visited the factory. They told her that it was a good idea, but they never actually followed through with implementing the change. So she did what any determined mother would do and wrote a letter to the President.

"I have two sons out there some where, one in the Pacific Island the other one with the Atlantic Fleet. You have sons in the service also. We can't let them down by giving them a box of cartridges that takes a minute or more to open, the enemy taking their lives, that could have been saved had the box been taped with a strong cloth tape that can be opened in a split second... Please, Mr. President, do something about this at once; not tomorrow or soon, but now."

- from Vesta Stoudt's letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 10 February 1943

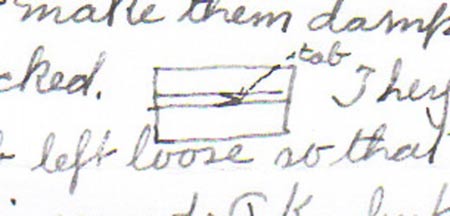

In her letter, Stoudt not only gave an impassioned plea and a detailed outline of her idea, but also provided drawings to illustrate her point.

Illustration from Vesta Stoudt's letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 10 February 1943. Photo from Kilmer House, courtesy of Kari Santo, Stoudt's great-granddaughter.

President Roosevelt passed her letter along to the War Production Board, who wrote back to Stoudt a few weeks later: "The Ordnance Department has not only pressed the matter, but has now informed us that the change you have recommended has been approved with the comment that the idea is of exceptional merit."

Shortly thereafter, the new tape was developed and rolled out – and not just for ammunition crates. Soldiers found that they could use it to repair practically everything, from weapons to vehicles to holes in their boots. They took to calling it '100-mile-per-hour tape' because it would hold even when affixed to fast-moving vehicles or when exposed to extreme winds. It was also called 'duck tape' – yes, you read that right – because it was made from cotton duck cloth (a type of canvas fabric) and because of its water-resistant properties.

Believe it or not, duct tape was originally called 'duck tape' because of the cloth material used in its development and because any moisture slid off it like water off a duck's back. Photo: drflet via Getty Images.

Duck tape eventually became 'duct tape' when it was introduced into the civilian market and used to patch up heating ducts during the post-war construction boom. It was also changed from its original army green colour to the distinctive silvery grey that we know today.

Vesta Stoudt did not invent duct tape (versions of which had existed since at least the beginning of the 20th century). But her idea and her persistence led to the development of the modern-day version and its wide-scale adoption during and after the war. It has since been used not only for military equipment and home repairs, but also to make countless wallets and prom dresses, to seal wounds and staunch bleeding, and even to help astronauts explore the Moon!

Duct tape was used on the Moon to attach pieces to the lunar rover. Photo: NASA/public domain

5 - CARGO PANTS

The original cargo pants (or cargo trousers) were introduced as part of the British Battle Dress Uniform in 1938. They featured one pocket on the side thigh and one on the front hip, providing storage and quick access to essential gear, from medical kits to ammunition.

During the Second World War, the cargo-pant concept migrated across the Atlantic, when Allied forces in the United States caught on and further innovated upon the idea. Cargo pants became a staple of US paratroopers in particular, who had to carry all of their gear with them as they jumped out of airplanes. The US version, sometimes called 'paratrooper pants', widened the pockets so that soldiers could carry maps, ration packs, radios – everything required for a long mission behind enemy lines. In his war diary, a German officer, rattled by the sudden appearance of paratroopers around his outpost in the night, described them as "devils in baggy pants".

Cargo pants, from soldier to runway. Photo (left) from QM Fashion. Photo (right) from Yahoo Life, Victor VIRGILE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Cargo pants entered the civilian world as demobilised troops went home after the war. They became popular with labourers, who stored their tools in easy-to-reach pockets, then with outdoor sport enthusiasts, like hunters and fishers. In the 1990s, they took off as a fashion trend, trickling up from hip-hop performers to high-fashion runways.

Cargo pants and shorts have become a curiously cross-demographic piece of apparel, existing at the peculiar nexus of dorky dads, ironically clad Gen Z youth, long-distance hikers, grease-stained mechanics and haute-couture fashionistas. To this day, they remain the indisputable king of pockets, whether they're carrying barbecue tongs, cell phones, granola bars, monkey wrenches or lipstick.

6 - SUPER GLUE

In 1942, during the Second World War, a young scientist named Harry Coover got a job as a research chemist for a defence contractor. His first assignment was to develop a material that could be used to make high-precision targeting sights for weapons. While experimenting with a variety of compounds, Coover created a substance that wouldn't work at all for the project – "the problem was, everything was sticking to everything!"

Technically called a synthesised cyanoacrylate, the super sticky substance was shelved away and duly forgotten. The government cancelled the defence contract.

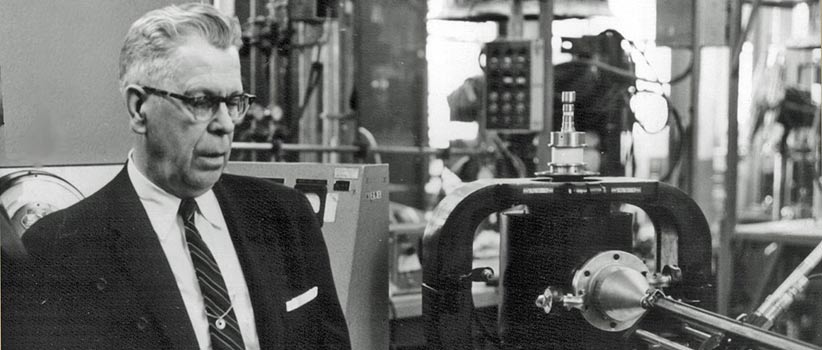

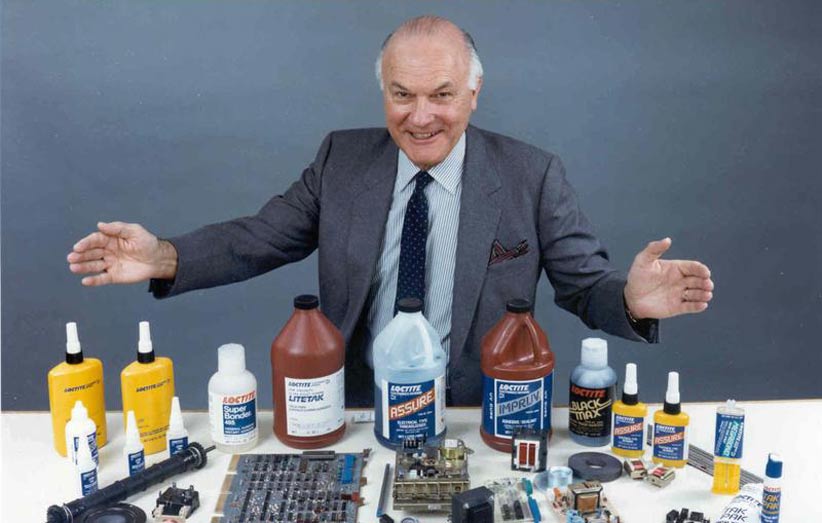

Dr Coover shows off products derived from his invention. Photo: National Science & Technology Medals Foundation.

Nearly a decade later, in 1951, Coover was leading a team on another research project, this time to develop temperature-resistant chemical coatings for fighter jet canopies. One of his research assistants, Fred Joyner, was going through a long list of potential compounds when he happened to test the previously shelved substance in his refractometer – accidentally gluing together its two lenses and ruining the USD 3,000 machine.

Joyner was mortified by his expensive mistake, but Coover immediately saw the commercial opportunity that he had previously overlooked. "Serendipity gave me a second chance," he later said in an interview after receiving the United States' National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

In 1956, Coover officially received a patent for "Alcohol-Catalyzed Cyanoacrylate Adhesive Compositions/Superglue". He went on to introduce his invention to the world on the TV gameshow "I've Got a Secret" in January 1959. Coover used a single drop of Super Glue to connect two pieces of metal together and lift the host – and himself – off the ground, to the cheers of the studio audience.

Coover and Garry Moore, host of "I've Got a Secret", demonstrate the remarkable strength of Super Glue. Footage: National Science & Technology Medals Foundation.

According to his daughter, Coover liked being known as 'Mr. Super Glue' and one of his proudest accomplishments was knowing that his invention was helping to save lives – medics started carrying bottles of Super Glue in spray form to treat wounded troops on the battlefield. The adhesive reacted with blood and skin, allowing medics to literally glue wounds closed, keeping soldiers from dying of blood loss before they could get to a hospital. A variation on the compound that was less irritating to the skin was eventually developed, and is now used by civilian paramedics around the world.

From sealing wounds and saving lives to reassembling broken knick-knacks, the only limit to Super Glue's applications seems to be the human imagination. As Dr Coover put it when receiving his medal, "It probably is the single material that has more uses than any other material that we have."

7 - AVIATOR SUNGLASSES

Photo: Alan Powdrill via Getty Images

Aviator sunglasses were developed in the 1930s as a lighter, less cumbersome alternative to the fur-lined goggles worn by pilots in the early years of aviation (think of Snoopy's goggles from Charlie Brown comics). Those types of goggles were heavy and uncomfortable to wear, and could also fog up mid-flight, making it hard for pilots to see (which is a pretty fundamental part of flying a plane).

Once cockpits were completely encased with glass, it became less important to have bulky eyewear that could protect against the cold. But it was still necessary to shield pilots' eyes from the blinding sunlight in the upper atmosphere, which could decrease visibility and cause headaches during long flights.

So Colonel John Macready of the US Army Air Corps worked with a company to develop the first set of aviator sunglasses, called Ray-Bans because that's what they were for: banning the sun's rays from a pilot's eyes. Initially, they were much more expensive than regular sunglasses, and were only marketed to civilians as sporting equipment for fishers and golfers.

The original aviator lenses were green, to cancel out the intense blue and white tones of the sky. Photo: Murray and Haggerty Optometrists.

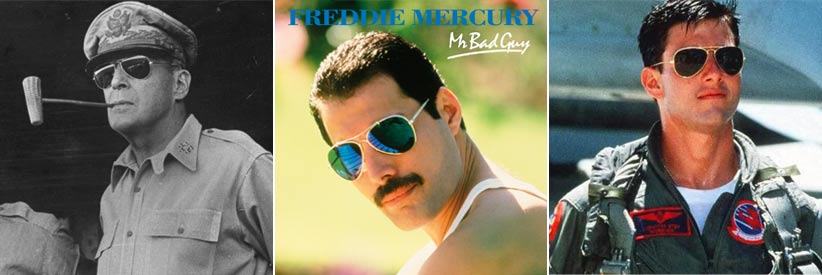

But the Second World War changed everything. Throughout the war, civilians back home saw thousands of pictures of pilots wearing the distinctive sunglasses. Even General Douglas MacArthur, one of the key commanders of US forces in the Pacific theatre, was shown wearing them while landing on a beach in the Philippines in 1944, a famous image of the war.

Aviators on famous faces: General Douglas MacArthur (left, photo from Murray and Haggerty Optometrists), Freddie Mercury (centre, photo from FreddieMercury.com) and Tom Cruise (right, photo from Gentleman's Gazette).

After the war, military styles continued to influence fashion trends. Aviators became hugely popular with Hollywood stars like Marlon Brando, and then with the wider civilian market. In the following decades, celebrities like Elvis Presley and Freddie Mercury maintained the status of aviators as iconic symbols of cool, and Tom Cruise popularised them in the 1986 hit movie Top Gun.

Aviators are still used by pilots around the world to this day. You have probably worn a pair yourself. After more than eight decades, the famous sunglasses have remained a fashion staple – classic, nostalgic and timeless all at once.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS:

We couldn't include everything on this list, so we'd like to shout-out a few honourable mentions that didn't quite make the cut. The list of everyday items that were invented or popularised by militaries is long, and includes:

- canned food,

- freeze drying,

- frozen juice concentrate,

- drones,

- jet packs,

- jet engines,

- EpiPens,

- blood transfusion,

- blood banks,

- weather radar,

- stainless steel,

- vegetarian sausages,

- tea bags,

- digital cameras,

- night vision,

- ambulances,

- aerosol bug spray,

- virtual reality,

- synthetic rubber,

- nylon and other synthetic fabrics,

- jeeps,

- penicillin,

- walkie-talkies,

- Silly Putty,

- the Slinky,

- T-shirts,

- safety razors,

- sanitary pads,

- wristwatches and

- computers.

Nobody knows what the next big innovation will be. But our armed forces will continue to experiment and invent, coming up with new ideas and new technologies that help maintain the basic security and stability of our societies – and, in some cases, when the stars align, become central pillars of our everyday lives.