Origins

My country and NATO

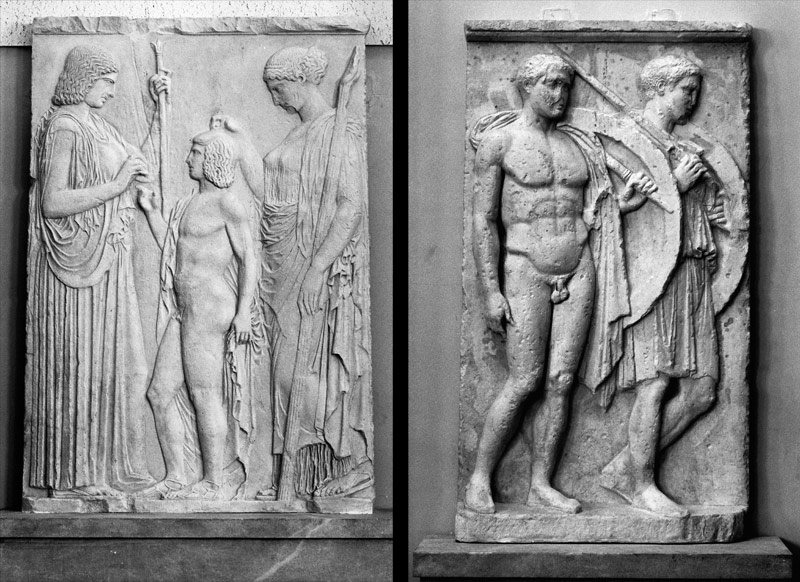

Greece and its NATO Allies in 1952

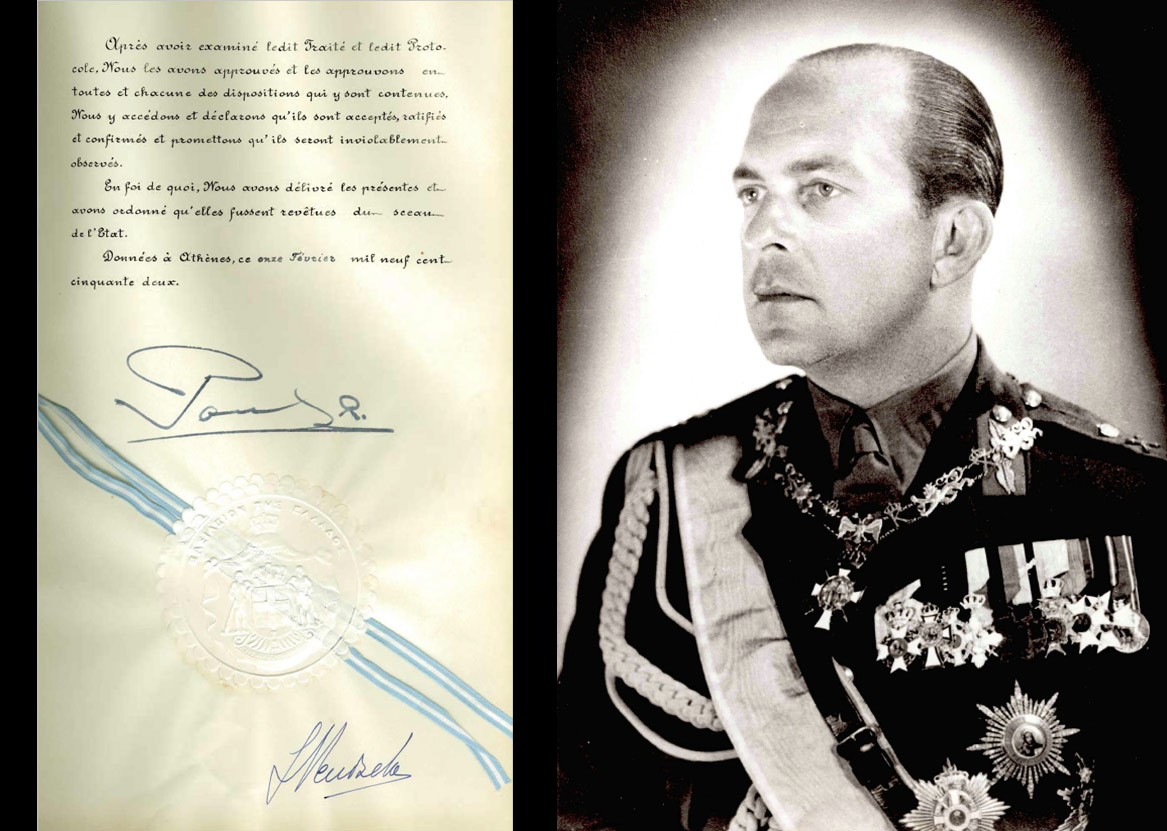

His Majesty King Paul I, king of the Hellenes, signs the Instrument of accession for Greece in Athens on 11 February 1952.

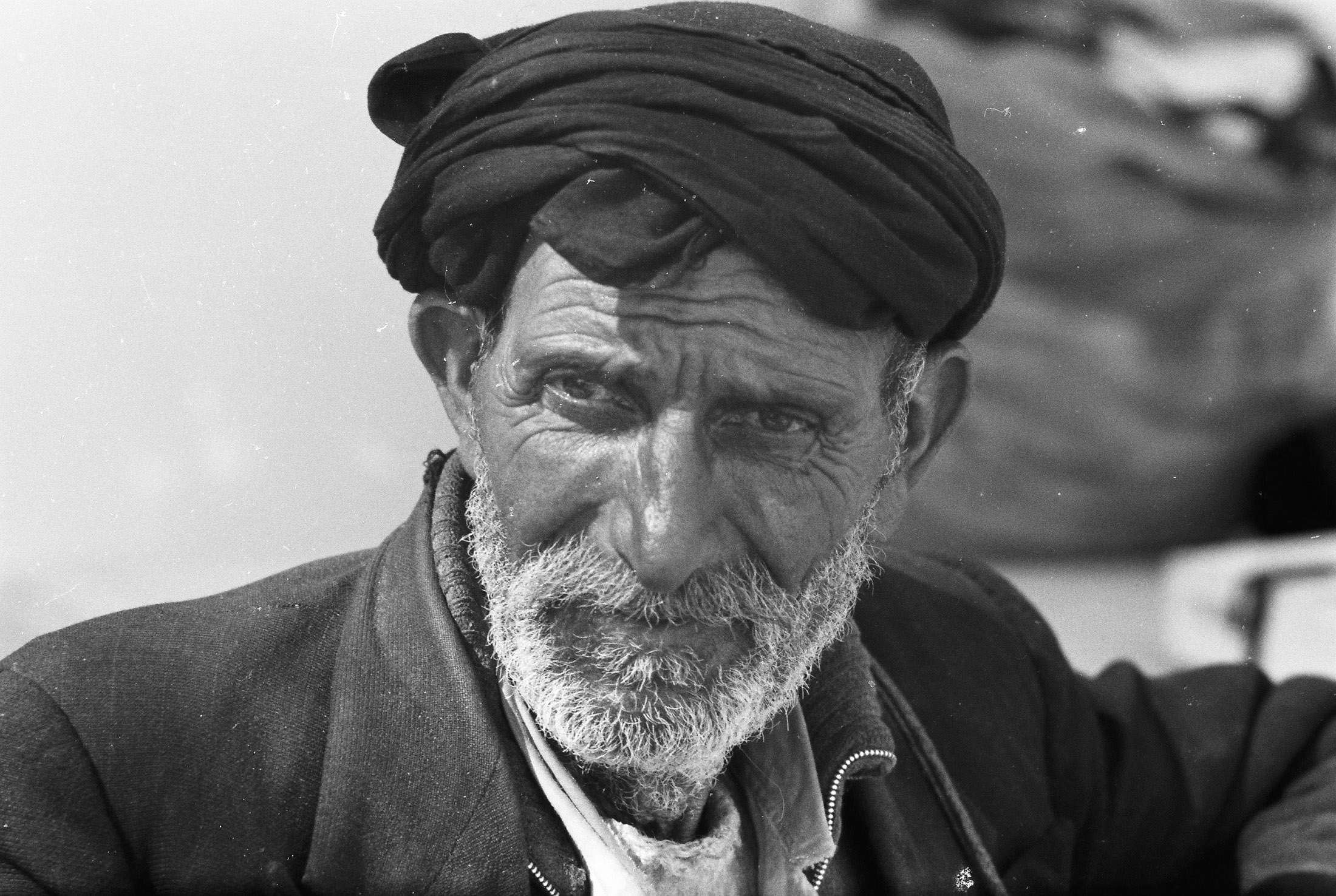

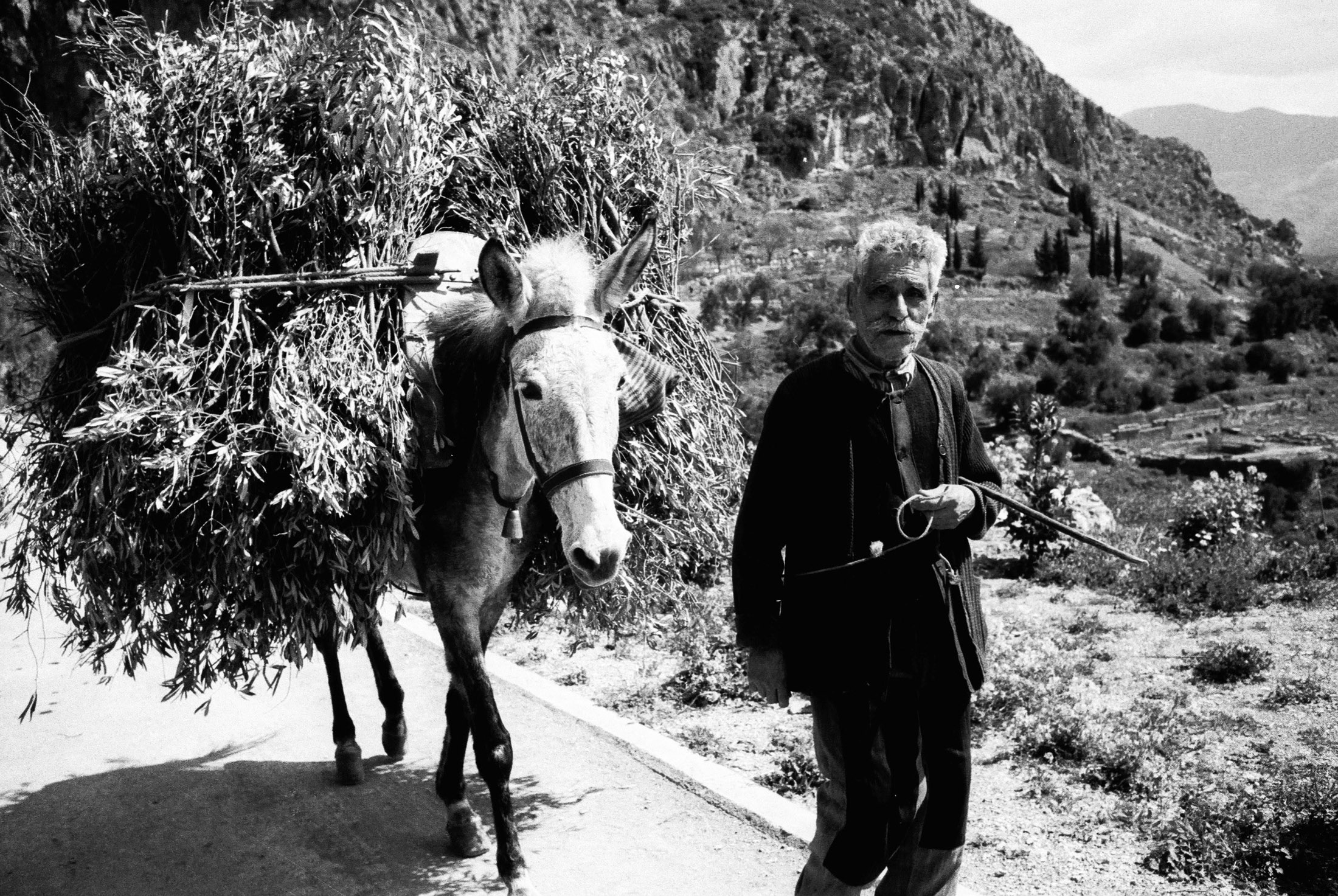

The Hellenic Army could only defend parts of this extensive border. The soldiers of the 604th Infantry Battalion in Evzoni uniforms on the steps of the famed border station with Yugoslavia (left) could only receive supplies from fellow troops by mule in the earlier days (right). It was at this very border station in 1913 that Bulgarian troops surprised nine Evzoni. They executed the Evzoni in the nearby village of Machikovo; the village was renamed Evzoni in honour of those who died.

NATO organised military exercises in the southeastern region of the Alliance throughout the Cold War.

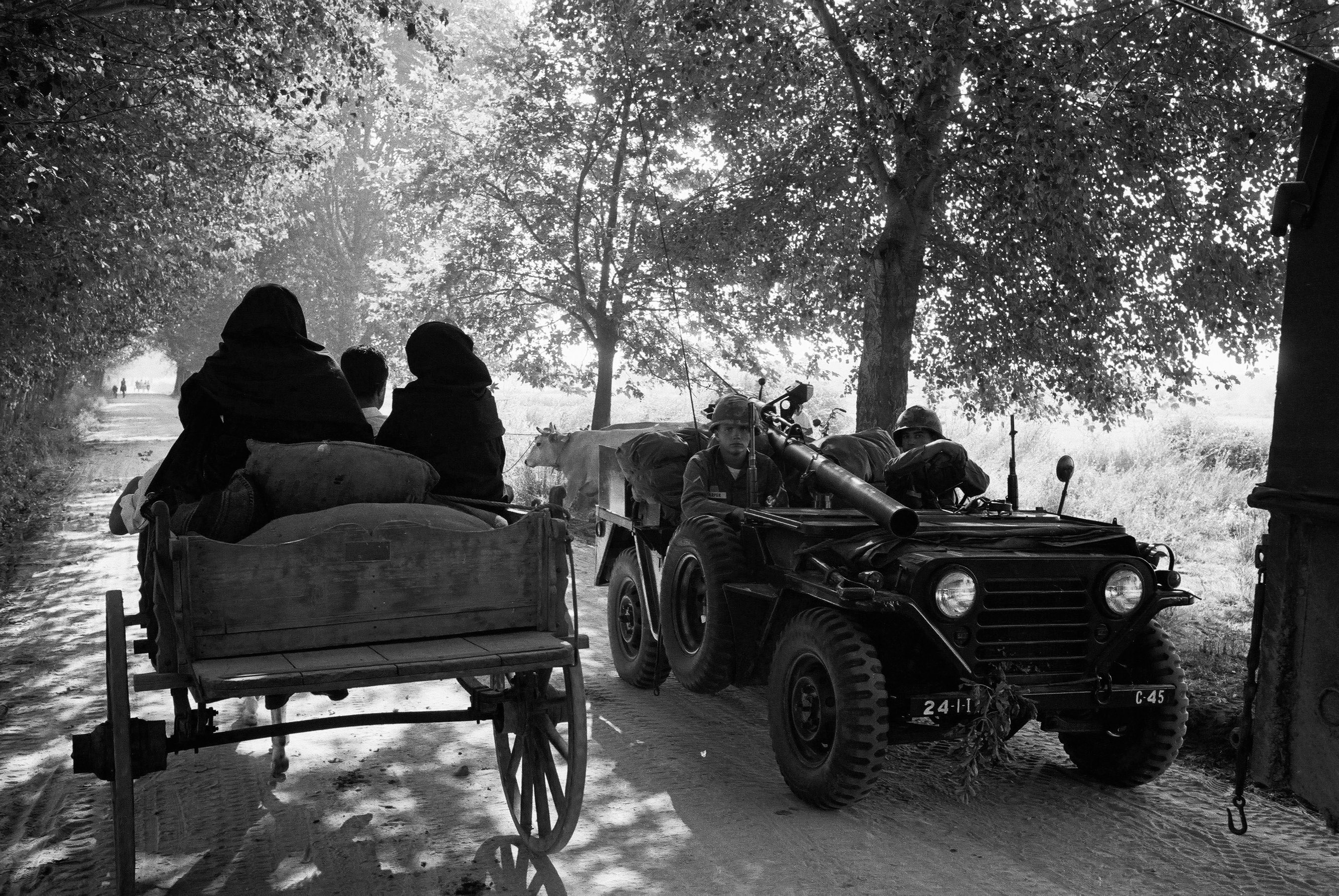

Despite political tensions, exercises were sometimes organised simultaneously in Greece and Turkey, as was the case in 1966. Here, multinational forces drive through border control between Greece and Turkey.

The forces moved from Exercise Summer Marmara, which took place in Greece from 31 August to 12 September 1966, to northwestern Turkey for Marmara Express (15-27 September).

These large scale field training exercises sought to test procedures and train troops from NATO’s ACE Mobile Force to operate in the region and become accustomed to the terrain, flying conditions and the climate.

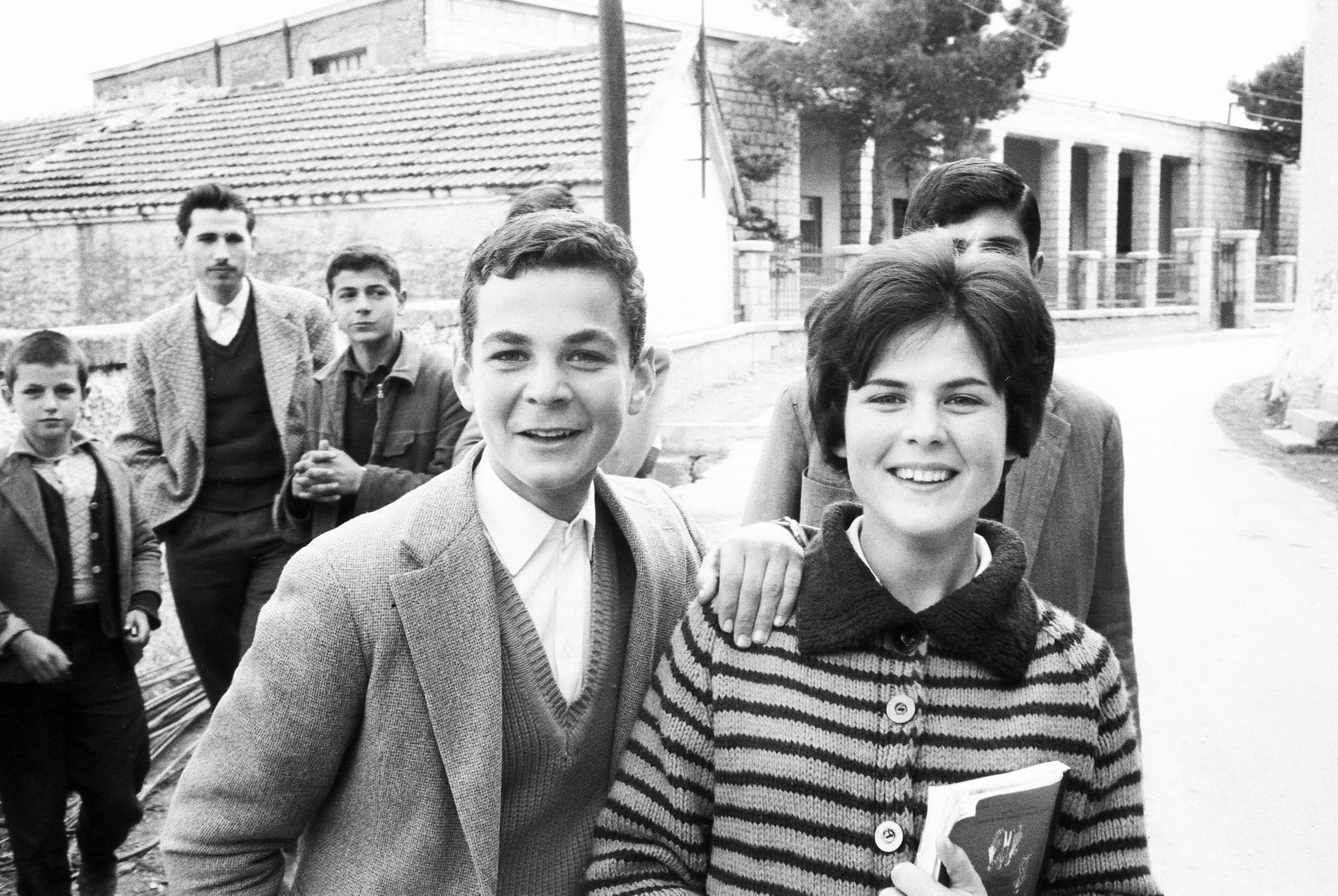

Wherever NATO exercised, troop manoeuvres attracted the curiosity of the local population. Here, during Exercise Summer Marmara, crowds rush to see military convoys pass by.

Local children are intrigued by one of the jeeps driving through the village.

Convoys ensure that locals can still go about their daily business.

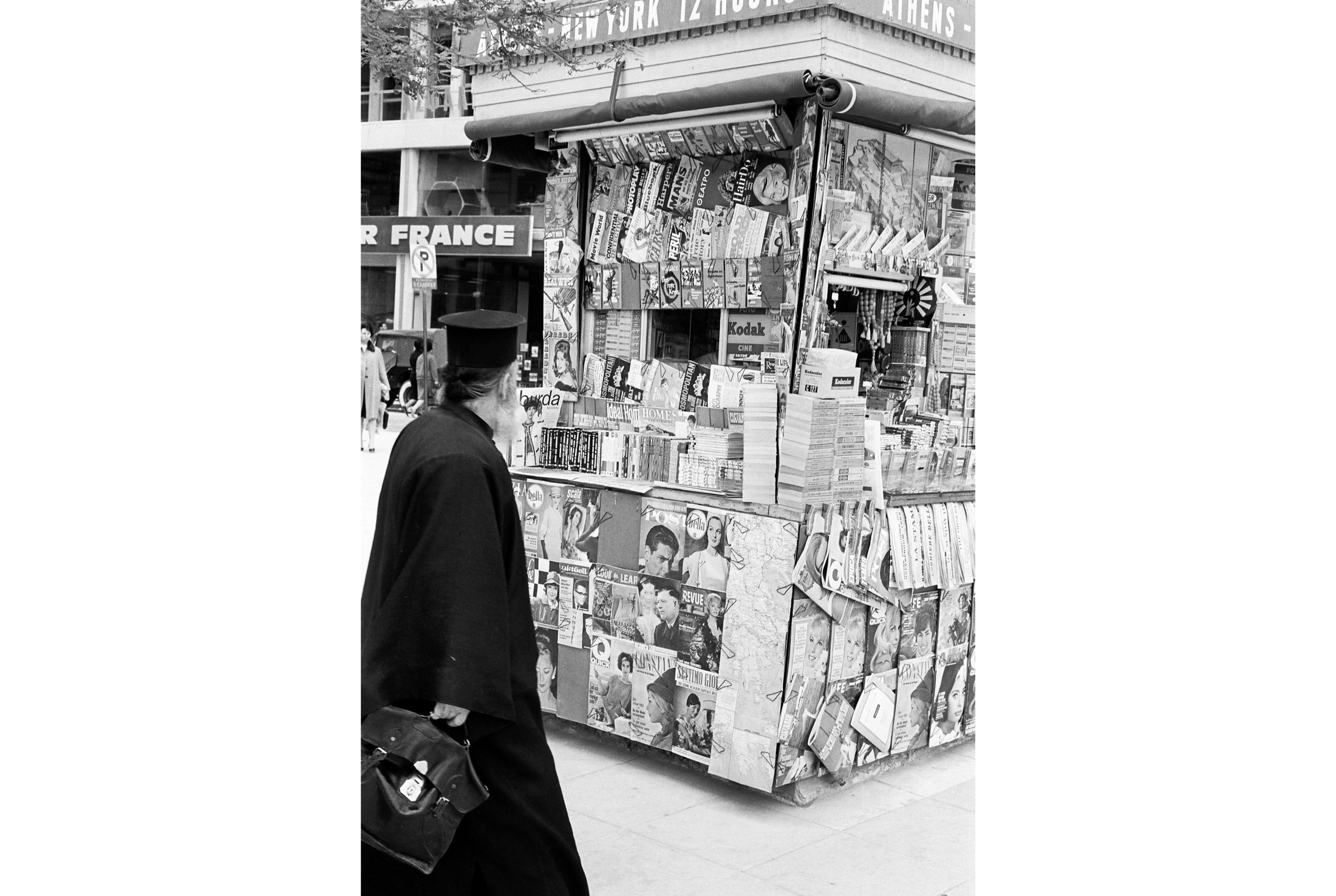

More unusual encounters occurred during exercises…

… as was the case here too!

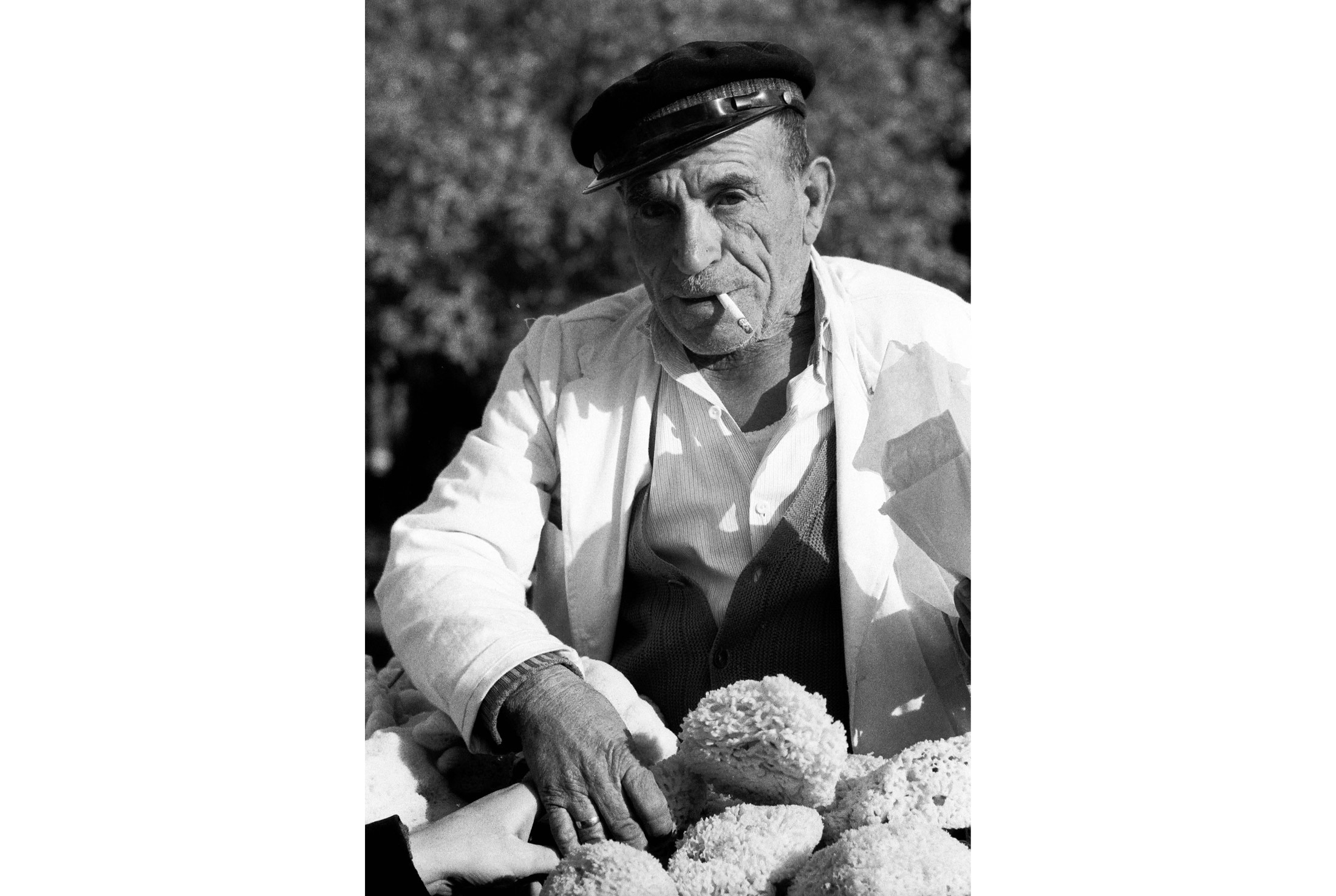

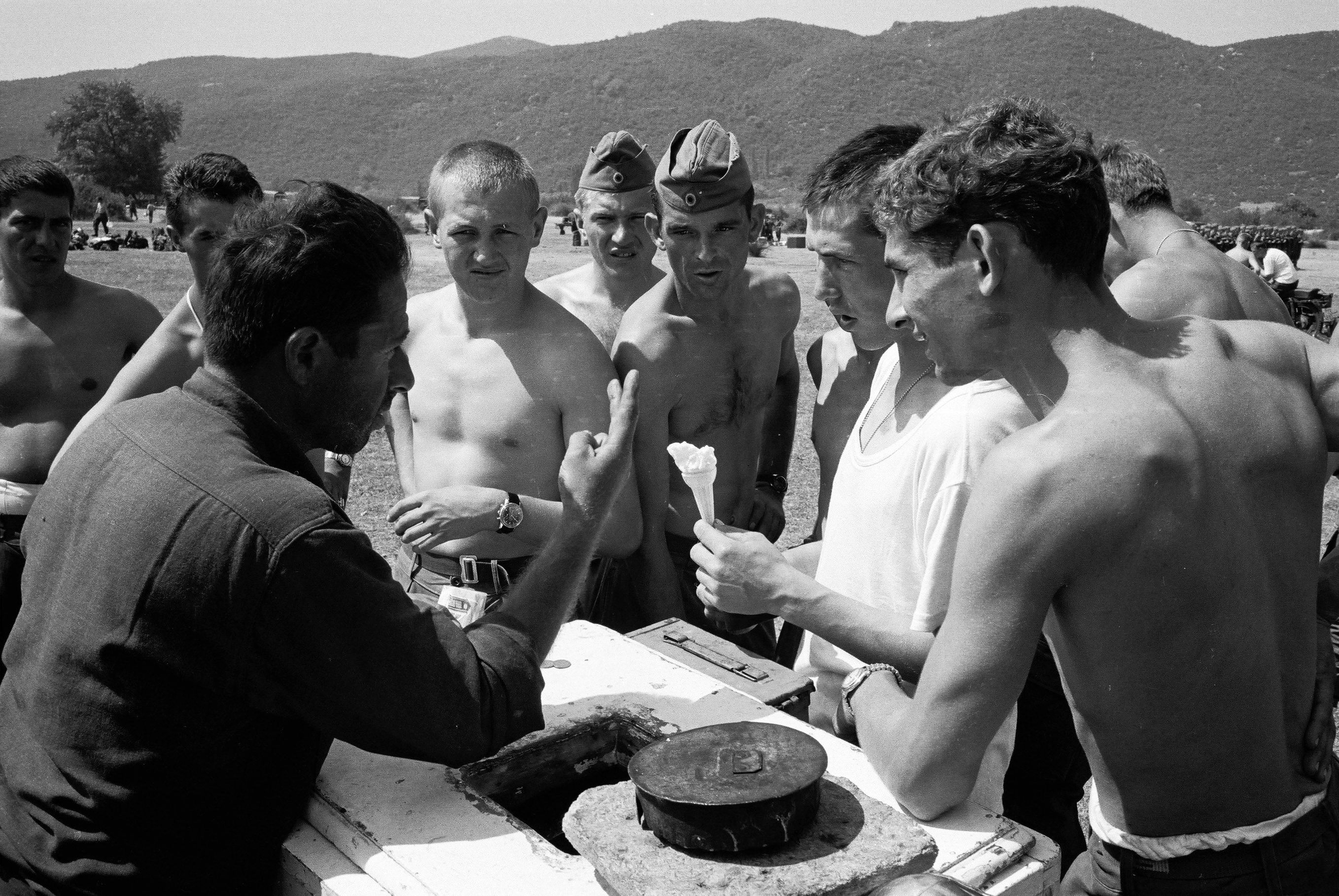

Training conditions could be harsh. The intensity of the heat was still strong in September so locals kindly offered water…

… or sold ice-creams!

And while some hid from the sun…

…others soaked it up.

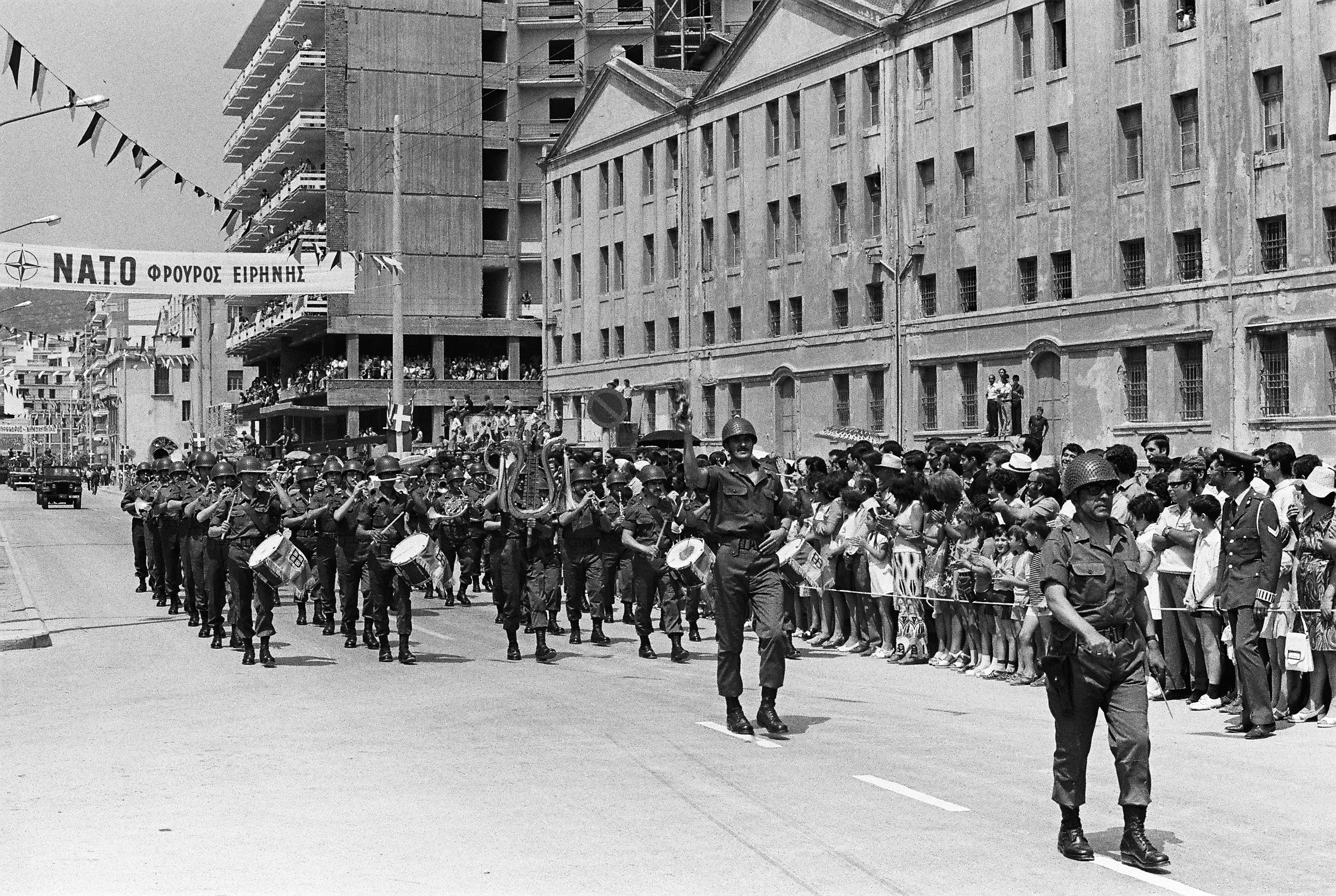

The Alliance’s AMF – or ACE Mobile Forces – frequently trained in Greece.

From 15 June to 5 July 1973, Exercise Alexander Express took place in Northern Greece.

Around 6,000 troops and over 1,000 vehicles participated in the exercise.

Forces from Greece, the United Kingdom, the United States and the southern and central region of NATO participated in the exercise.

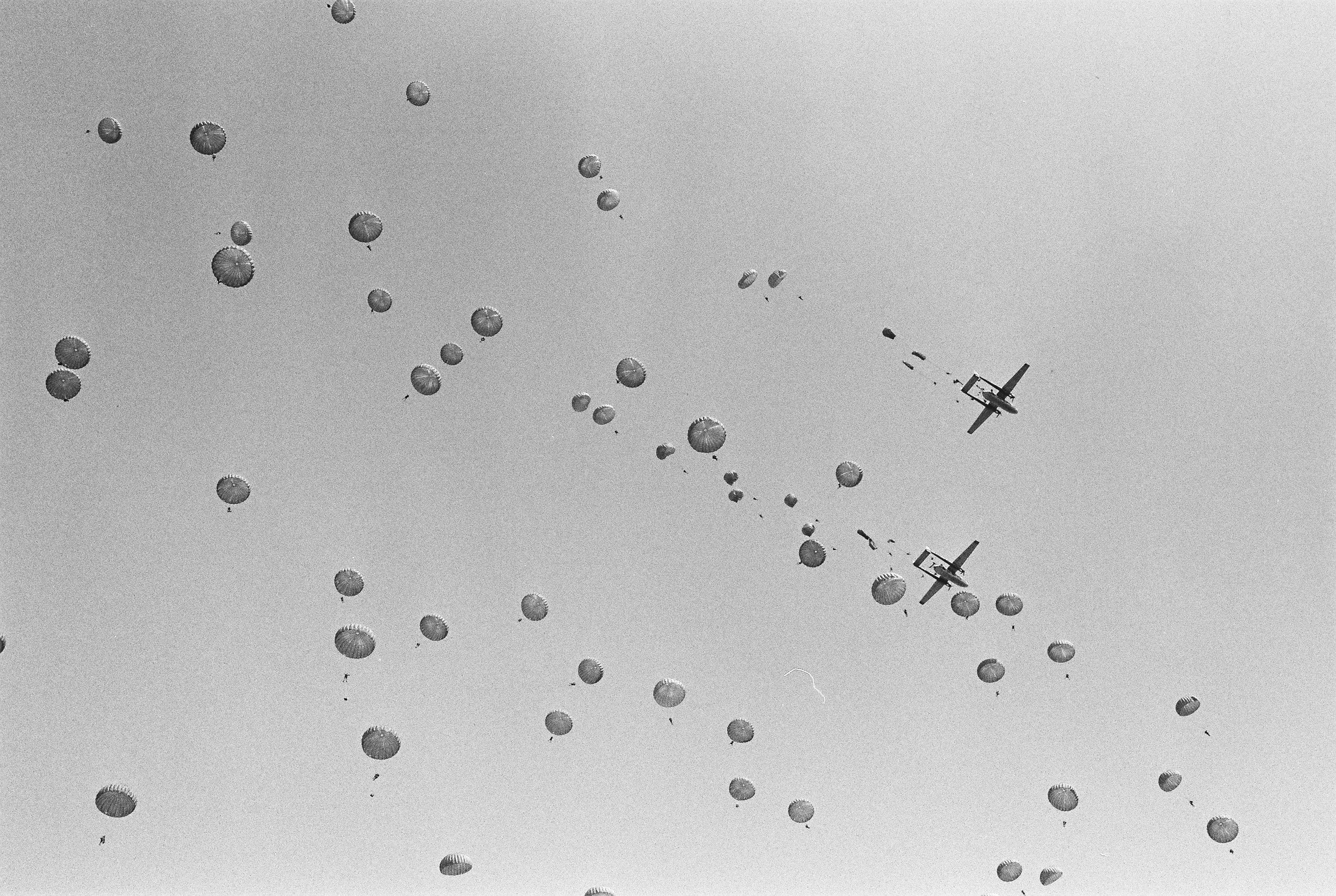

Many were moved in by air.

They were airlifted to Greece from home stations in other parts of Europe.

Standard procedures and manoeuvres were tested throughout the exercise.

Sometimes the ACE Mobile Forces got caught up in traffic jams.

Here, a unique encounter in the plains of Northern Greece.

The Royal Hellenic Air Force on parade on the national day of Greece, 25 March 1954.

The Royal Hellenic Air Force on parade on the national day of Greece, 25 March 1954.