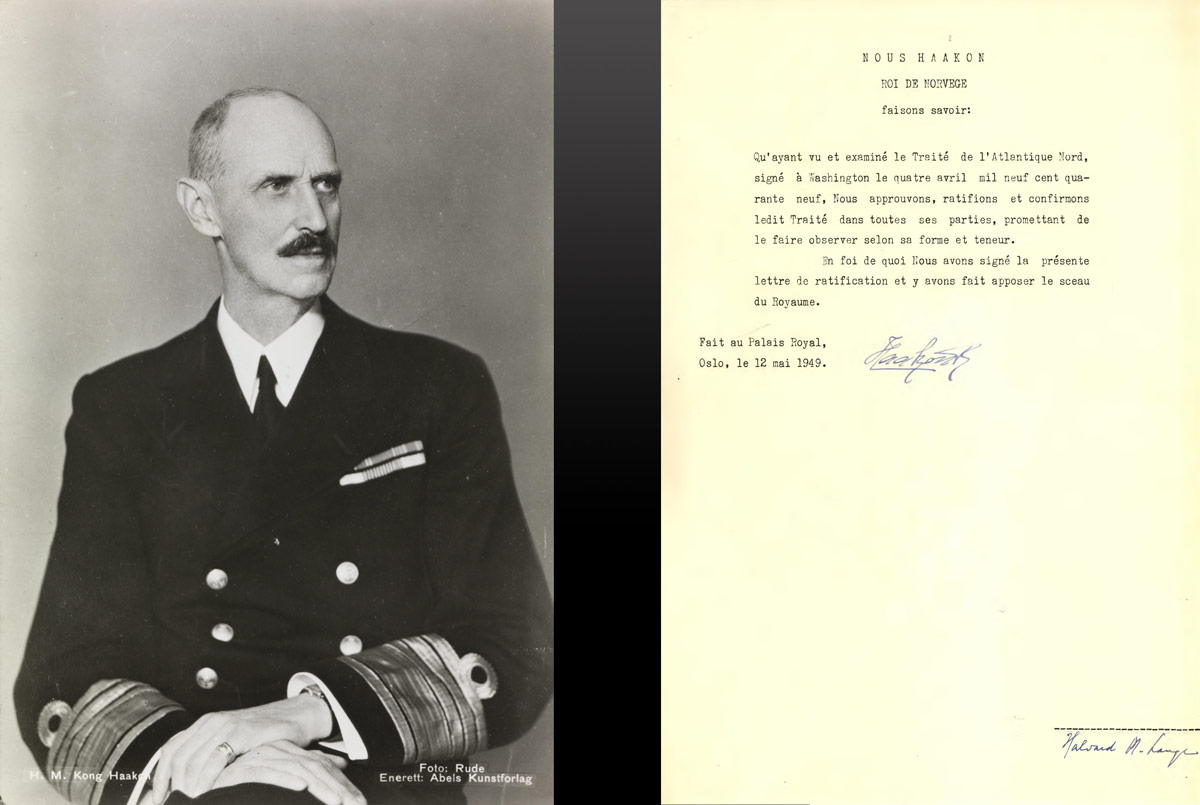

The overwhelming majority of the Norwegian people deeply believe that the signing of the Atlantic Pact is an event which may decisively influence the course of history and hasten the day when all nations can work together for peace and freedom.

Halvard M. Lange, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Norway at

the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington, D.C., on 4 April 1949

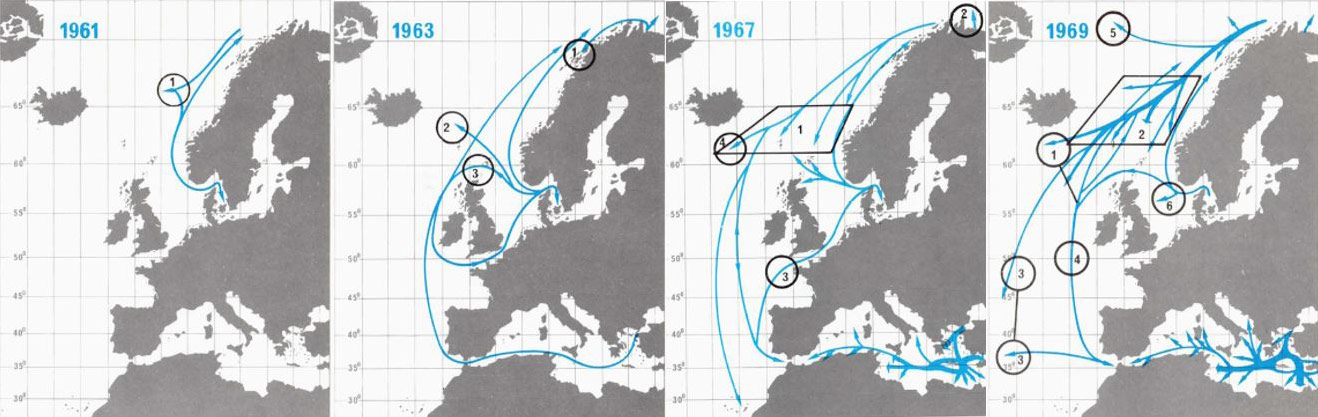

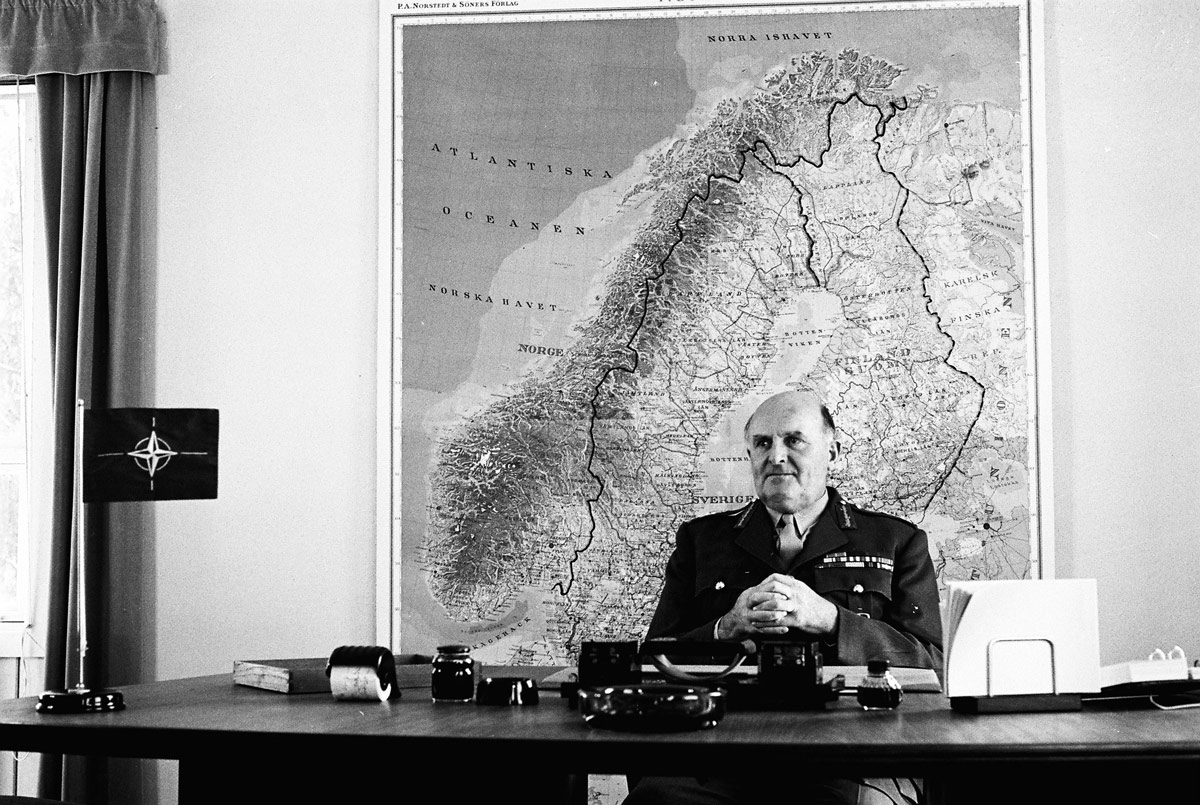

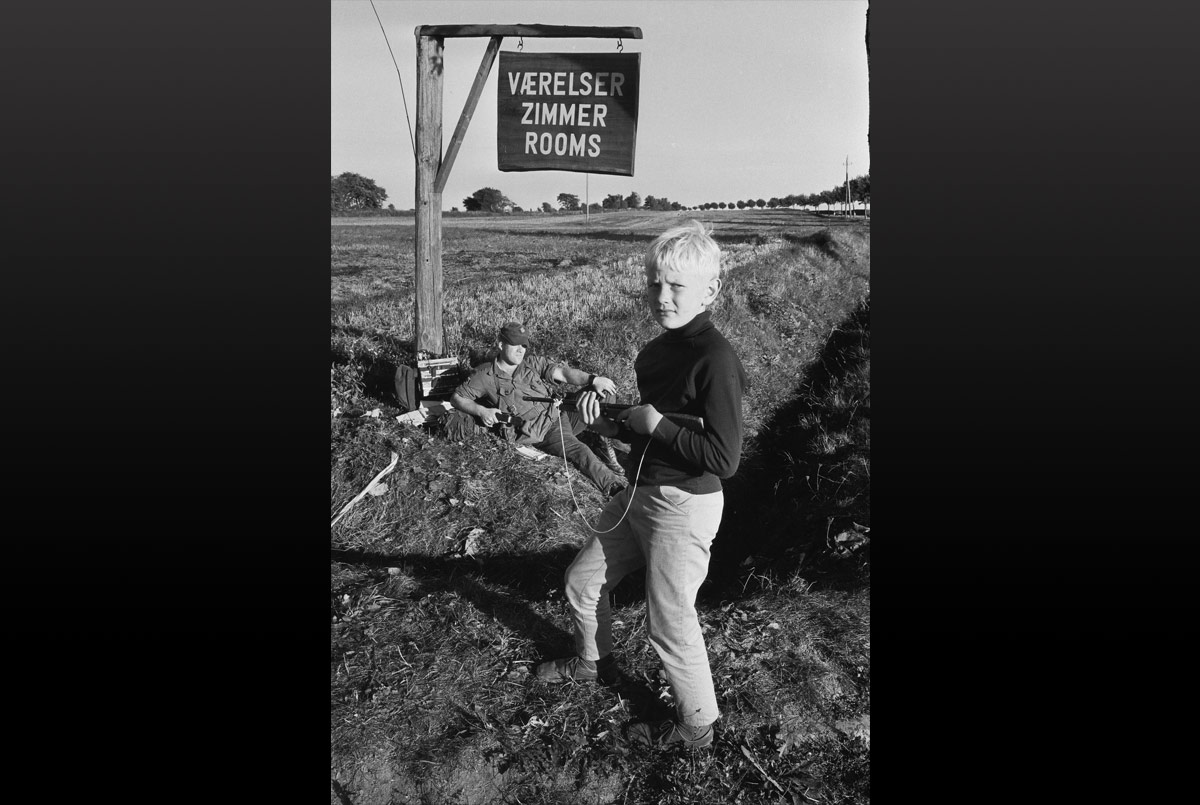

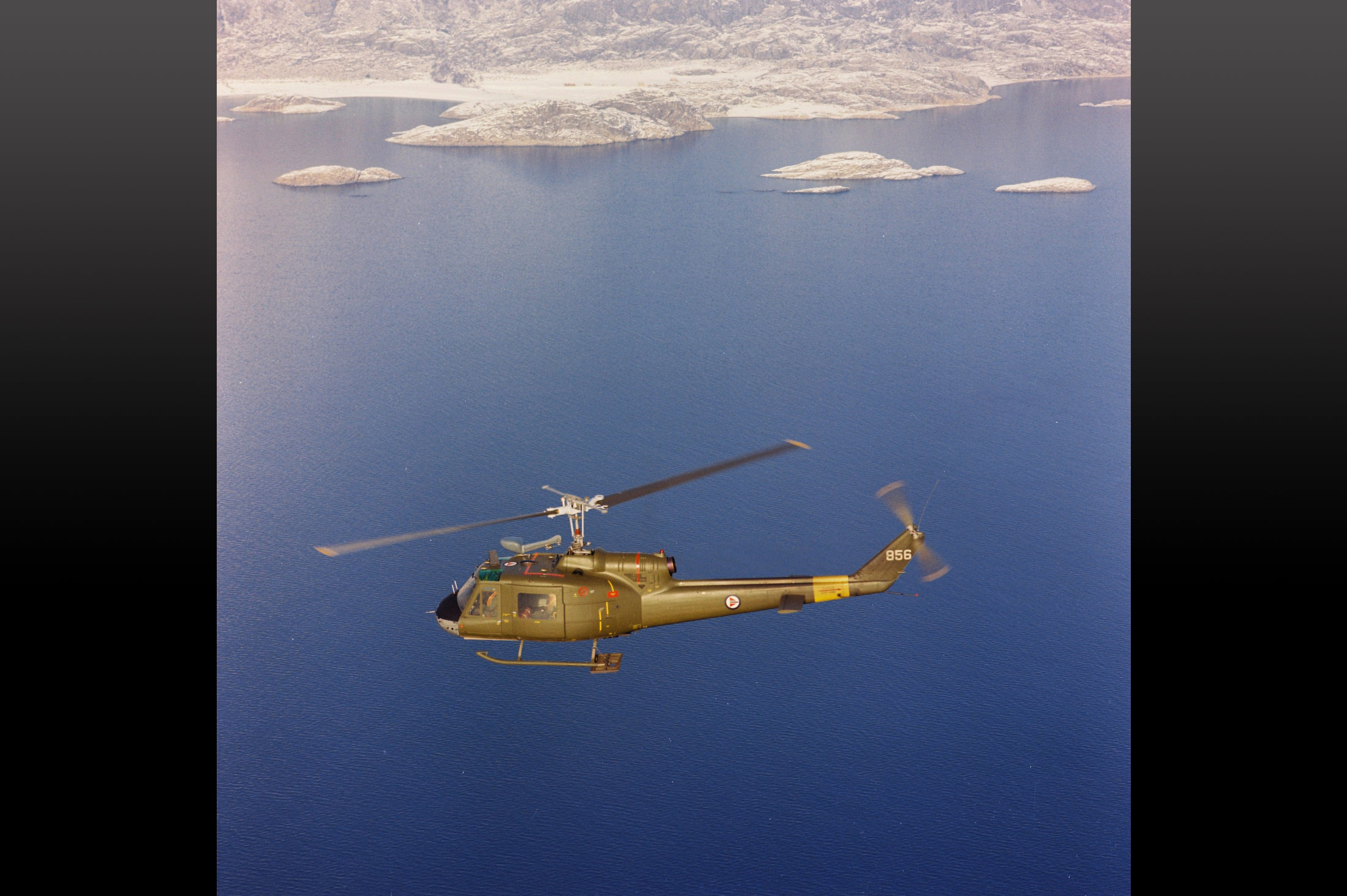

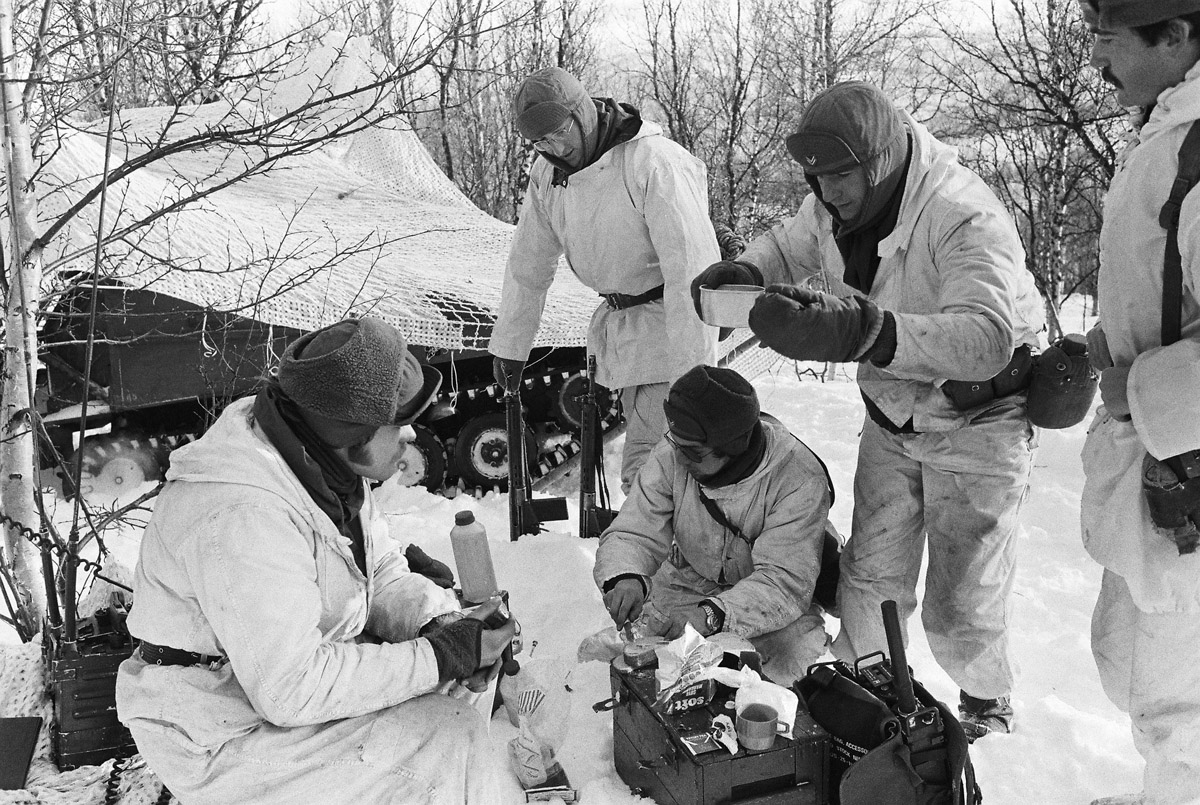

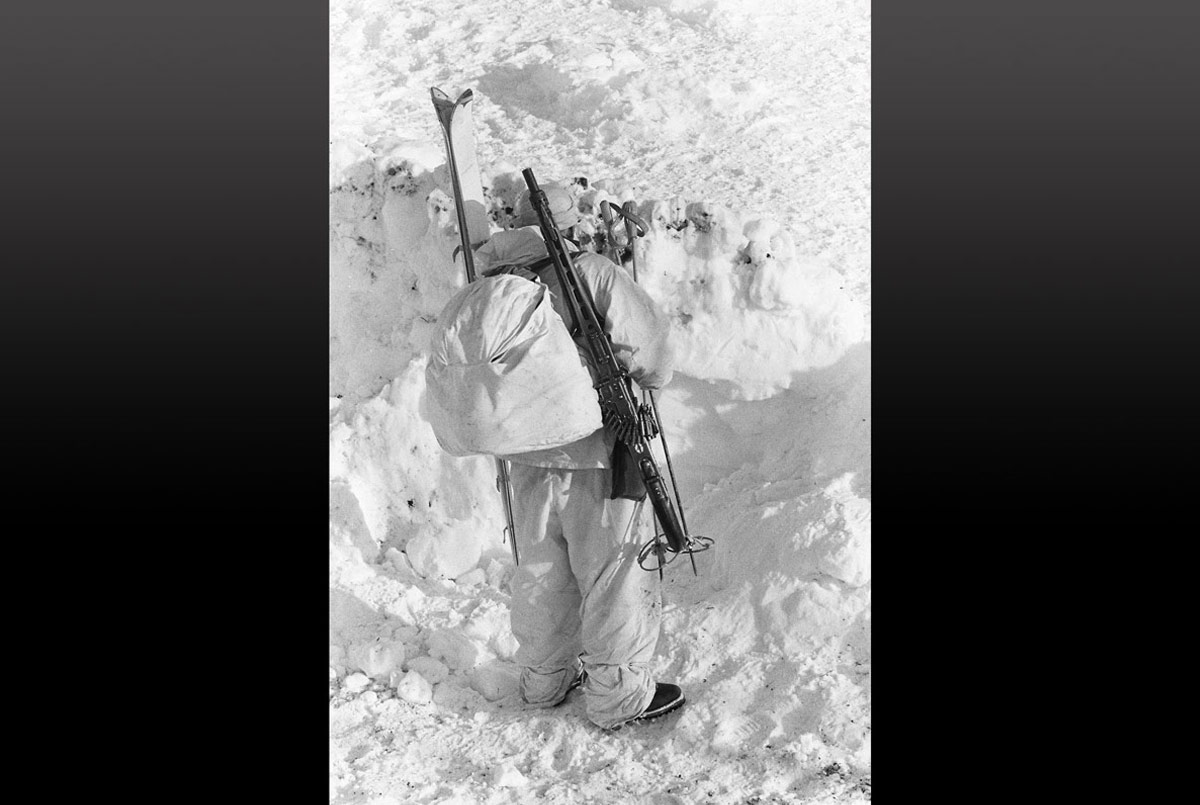

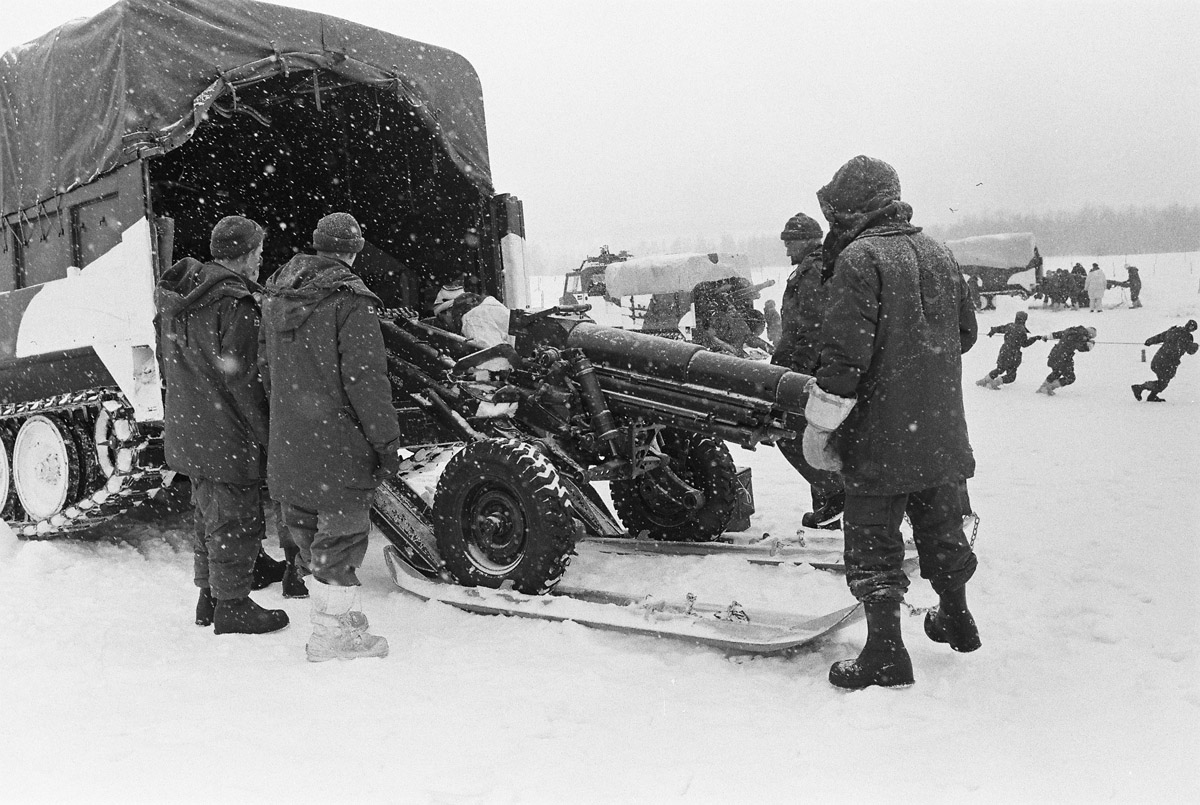

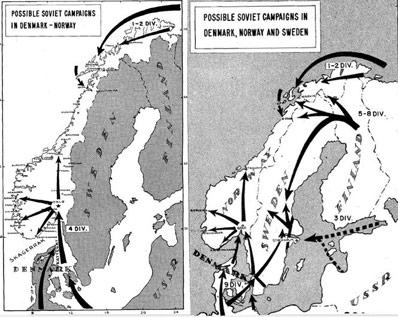

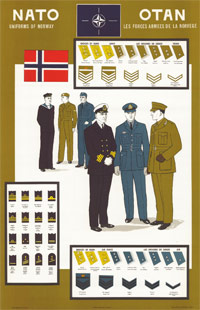

A land that lets the imagination wander with its fjords and aurora borealis, while attracting world attention each year with the Nobel Peace Prize, was also a founding member of NATO in 1949. Norway has an exceptionally long coastline and while that is an economic and strategic advantage, throughout history it has often counted on friendly forces to help protect its territory. The Western Allies did not want to leave Norway open to communist domination in the post-war era; and Norway understood that neutrality was no longer a viable form of defence. However, the 200-km border that Norway shares with what was the Soviet Union at the time, gives it a different outlook to international relations. Its refusal to host NATO bases from the very start stemmed from the delicate balancing act it had to pursue as a Western Ally with one of the biggest industrial-military power houses of the Soviet Union literally at its doorstep in the Kola Peninsula. The latter served as one of the largest naval and air bases for the Soviet Union during the Cold War, posing a direct threat to Norway.

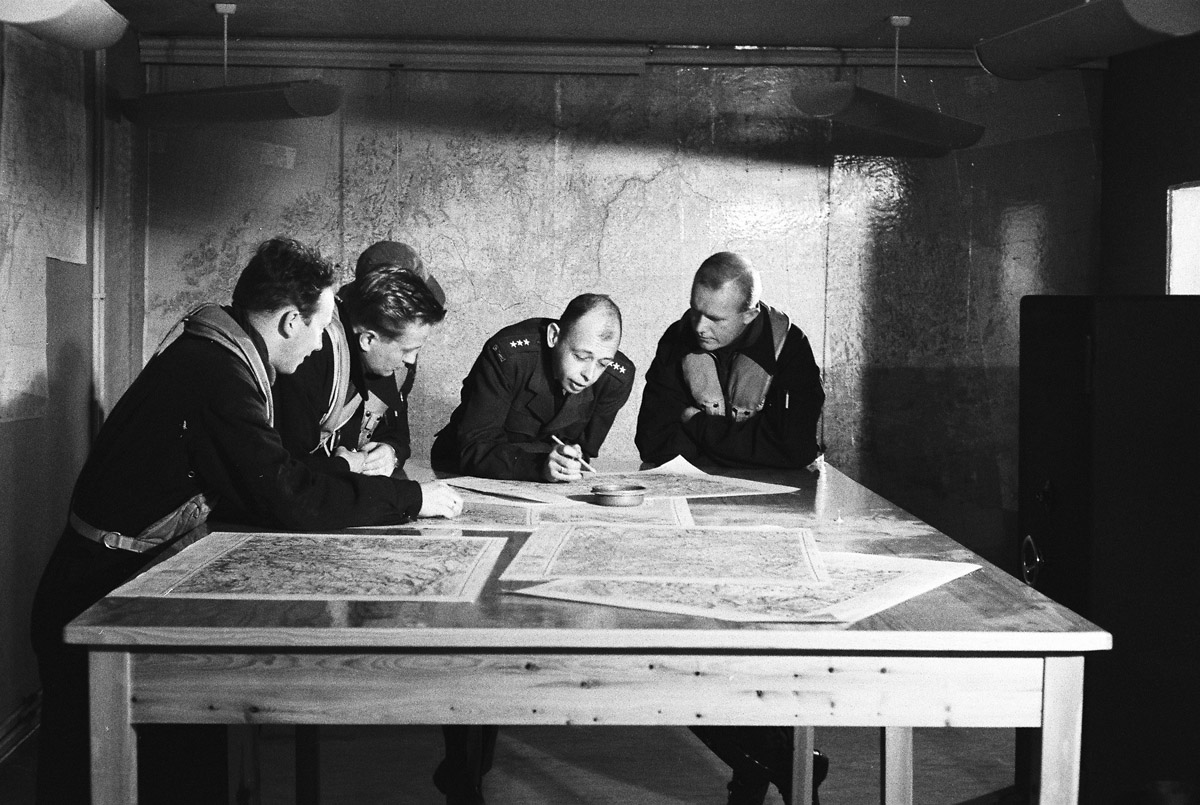

Norway’s shift to an “Atlantic policy” began in December 1940, the same year that saw the country’s neutrality violated and its land occupied. At the time, Trygve Lie was the Foreign Minister of the Norwegian government in exile in London. He believed Norway’s long-term security prospects were intimately tied to its far-away neighbours across the Atlantic. Occupation and war had shaken Norway’s traditional belief in neutrality, and a dramatic change in posture occurred.

Norwegians would rather die tomorrow on their feet than live a thousand years on their knees.

Wilhelm Morgenstierne, Norwegian Ambassador to the United States

Trygve Lie was convinced of the need for transatlantic security cooperation, which would at least include the United States, the United Kingdom and Norway – the United Kingdom historically having been a guarantor of its neutrality. In a speech broadcast from London to occupied Norway at the outbreak of the war, he focused on the need for cooperation and mutual security once conflict ceased. Lie was already a staunch advocate of this form of close international cooperation. He went on to become the first Secretary-General of the United Nations in 1946.

The Nordic option?

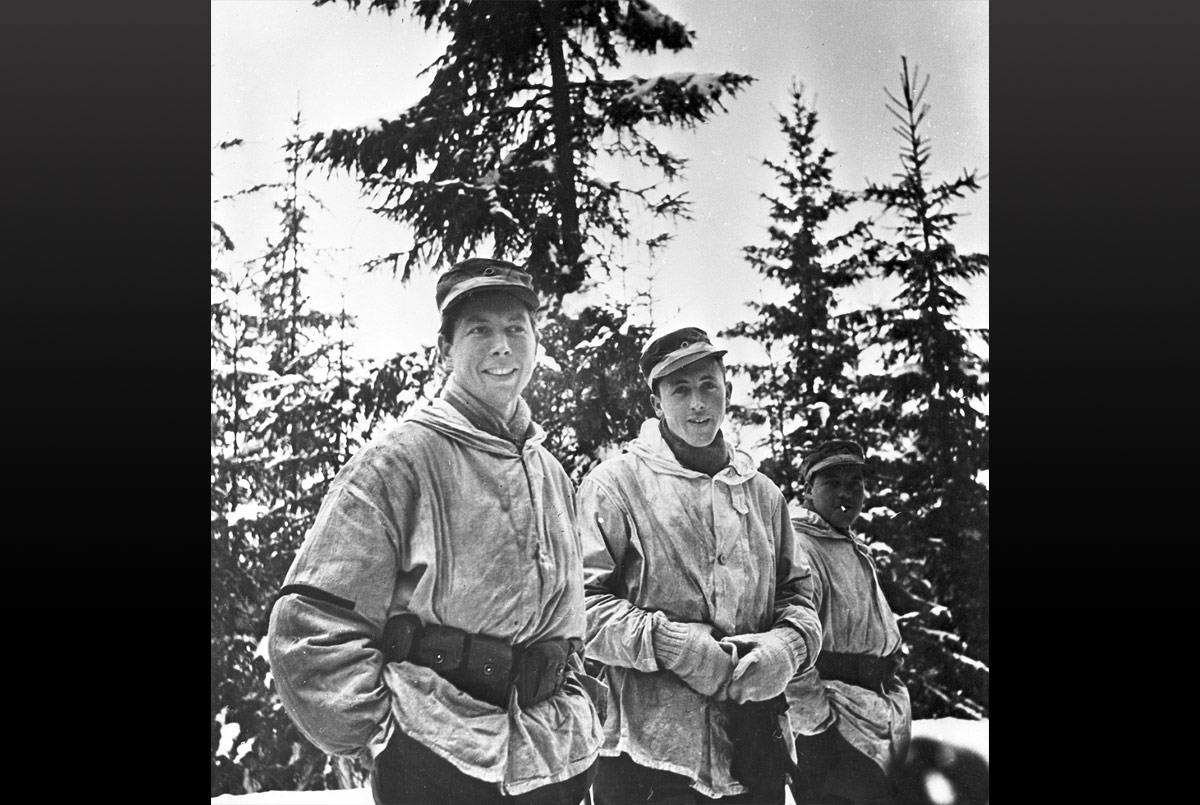

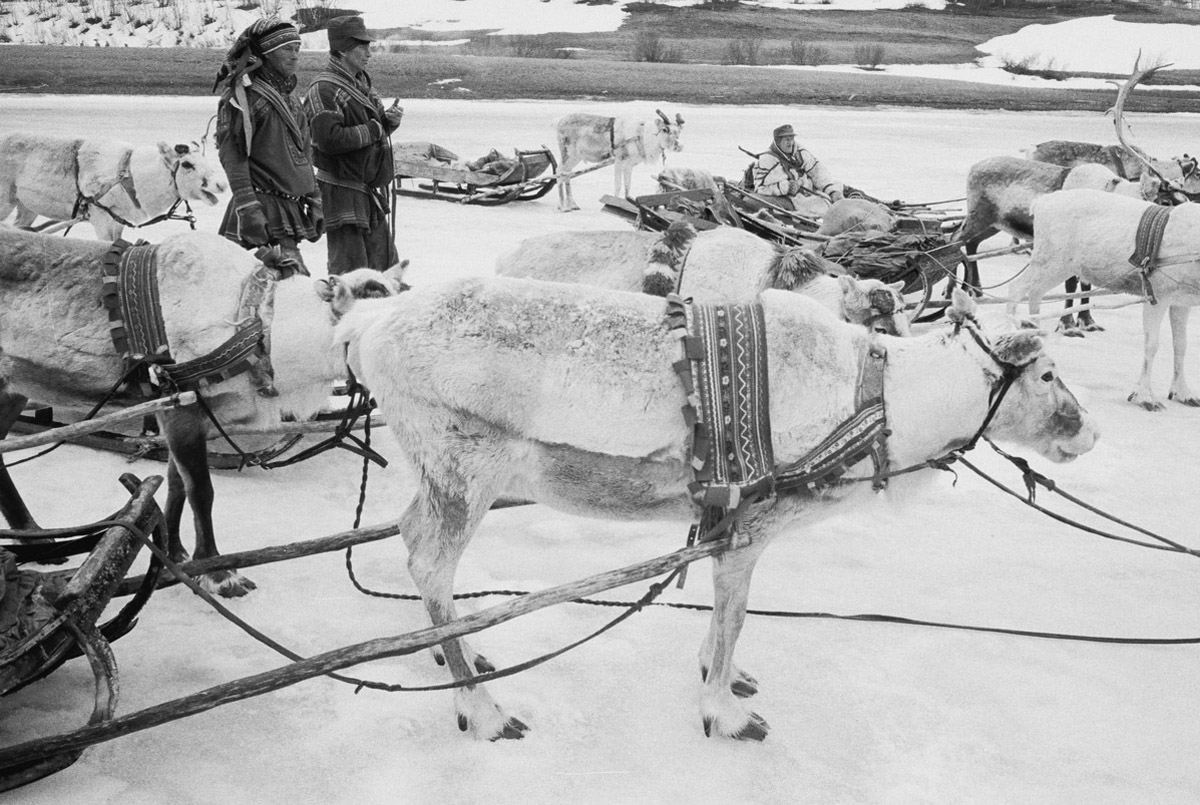

The end of the Second World War created a multipolar world in which Norway hoped to navigate as a mediator between the “blocs”. The prospect of complete and isolated neutrality was no longer credible in the eyes of the Norwegians. There was, however, an alternative: a “Nordic option” that could unite neighbouring countries in a defence pact. Sweden was the main driver of this endeavour. After failed attempts in the 1930s, it pushed for a federation in 1942 and then the idea of a “Nordic pact” re-emerged in January 1948. Denmark, Norway and Sweden met several times over a span of 12 months to consider the creation of a fully neutral bloc. Ultimately, this proposal was considered to be too weak to counter potential Soviet aggression. Norwegian politicians believed that a Nordic pact could only stand with military support from the United States and countries from Western Europe. Norway failed to reconcile this disagreement with Sweden and remained unconvinced that the Nordic option would truly guarantee security.

The coup d'état in Prague, the disappearance of Czechoslovakia as a free democratic state, was the last straw on the camel's back, or, if you prefer, the flash of lightning which forced open the most stubborn eyes.

Paul-Henri Spaak, NATO Secretary General, November 1957

The Czechoslovakian example, where a Soviet-backed coup took over the entire country in February 1948, shocked Norway and the Norwegians. Czechoslovakia and Norway were close after the war: their peoples had both been occupied and liberated, and both hoped to act as a bridge between East and West. Public opinion sharply turned in favour of stronger defence guarantees, such as a potential North Atlantic Alliance. Two months later, Finland and the Soviet Union signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, putting increasing pressure on Norway to move closer to the West.

Similarly to Trygve Lie, Halvard M. Lange, who had started his political career in the 1930s, steered his country towards a Western alliance from his position of minister of foreign affairs (1946-1965). Norway decided to join the North Atlantic Alliance, which convinced both Iceland and Denmark to follow suit as founding members. Finland had signed a treaty with the Soviet Union and Norway’s last fellow Scandinavian country – Sweden – remained neutral throughout the entire period of the Cold War.