As NATO’s commander, Gruenther developed an awed respect among his staff for his efficiency, his energy, and for his ability to work with both a big-picture vision and microscopic detail. He greeted thousands of visitors to NATO every year, detailing the value of the Alliance to their own interests and remembering each person by name. His office had to deal with a constant flurry of “Gruenthergrams”—paper slips bearing his questions and commands—most of which were requests for the huge quantities of raw information her required.

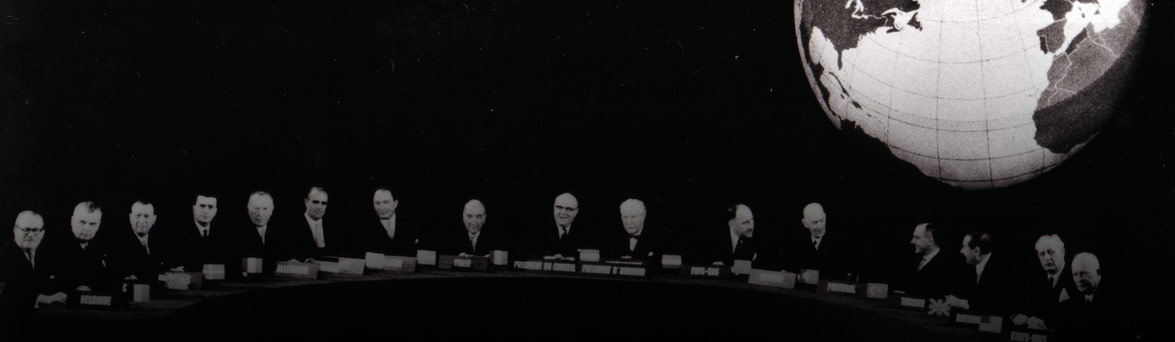

Gruenther oversaw the accession of West Germany to the Alliance in 1955. He also set up the New Approach Group, which officially shifted NATO’s strategy from a troop-based approach supported by artillery and air power, to an atomic-strike approach supported by troop movements. But his main role was as NATO’s tireless champion—using his enormous intellect, personal charm, and diplomatic skill to shepherd the organization through a period where the continued existence of the Alliance was not yet assured.

Ultimately, Al Gruenther’s story is one of humble roots and life-long service. According to residents of Gruenther’s boyhood town, the future four-star general was bullied and called a sissy in grade school for wearing knee-length trousers. After graduating fourth in his class from West Point, he spent 17 years as a second lieutenant before being promoted to captain. And after taking over as SACEUR, he faced the political challenge of reduced military commitments from nearly all NATO member states. Armed with little more than “a cascade of facts drawn from an incredible memory, an inextinguishable smile and a dry Nebraska lucidity,” Gruenther converted skeptics into supporters and left NATO stronger than he found it.

I think most people agree that NATO is the best instrument to insure the preservation of our freedoms. But basically, NATO is a state of mind, and the condition of the state of mind depends upon public support. Without that support the alliance could deteriorate rapidly.”