Secretary General's Annual Report 2012

Foreword

“Defence matters”

As the New Year starts, NATO Allies have been deploying Patriot missiles to help defend and protect Turkey’s population and territory and contribute to the de-escalation of the crisis along our south-eastern border. This follows our decision in December to augment Turkey’s air defence capabilities. This decision was a concrete demonstration of NATO’s solidarity and our steadfast commitment to the security of all Allies. It also made clear why defence still matters.

2012 saw many other examples of Alliance solidarity. At our Chicago Summit in May, we renewed our commitment to a sovereign, secure and democratic Afghanistan. We agreed that our current combat mission will be completed by the end of 2014, when our Afghan partners have assumed full responsibility for the security of their country, and that our engagement will then enter a new phase. We are already planning a new NATO-led mission from 2015 to train, advise and assist the Afghan security forces.

In Chicago, we also engaged our partners at the highest level. We reiterated that NATO’s door remains open to those countries that are willing and able to assume the responsibilities and obligations of membership, and we vowed to intensify our cooperation with partners across the globe.

In Chicago, we also set ourselves the goal of achieving forces that are more capable, more compatible, and more complementary – what we call “NATO Forces 2020”. To help achieve this goal, we agreed two separate initiatives – Smart Defence and the Connected Forces Initiative.

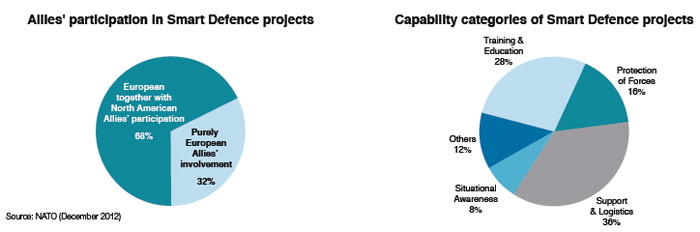

Smart Defence is the way forward for Allies to develop and acquire critical capabilities. More than 20 multinational capabilities are already being developed – from maritime air surveillance to precision-guided munitions. European Allies take part in all of these projects; they are leading two thirds of them; and one third of the projects are purely European in terms of participation.

The Connected Forces Initiative will help NATO and partner forces to build on the experience of two decades of operations, by increasing NATO-led training and exercises, including with a strengthened NATO Response Force. In fact, this Annual Report shows that most Allies have significantly improved their capacity to deploy and sustain their forces in recent years. Our Connected Forces Initiative will help us to maintain these gains as well as the ability of our forces to operate together. This will be especially important after our ISAF mission in Afghanistan ends in 2014.

I look back on 2012 as a year when we strengthened our transatlantic bond, demonstrated our commitment to our shared values and security, and made plans to ensure a stable and peaceful future for Allies and partners alike. In 2013, we must continue to display that same solidarity, commitment, and foresight, in order to sustain our strength and our success.

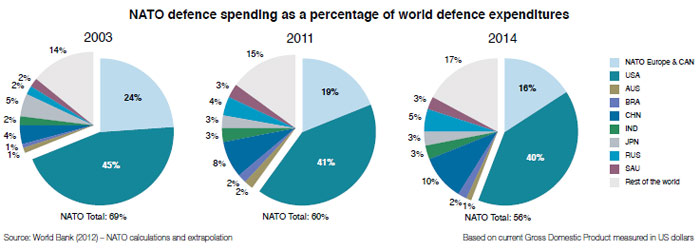

This Annual Report makes clear that, despite the economic crisis of the last few years, the Alliance remains the most important military power in the world. NATO countries continue to account for over half of global defence spending. However, defence spending among the Allies is increasingly uneven, not just between North America and Europe, but also among European Allies. Moreover, total defence spending by the Allies in recent years has been going down, while the defence spending of new and emerging powers has been going up. If these spending trends continue, we could find ourselves facing three serious gaps that would place NATO’s military capacity and political credibility at risk in the years to come.

There is a risk, first of all, of a widening intra-European gap. While some European Allies will continue to acquire modern and deployable defence capabilities, others might find it increasingly difficult to do so. This would limit the ability of European Allies to work together effectively in international crisis management.

Second, we could also face a growing transatlantic gap. If current defence spending trends were to continue, that would limit the practical ability of NATO’s European nations to work together with their North American Allies. But it would also risk weakening the political support for our Alliance in the United States.

Finally, the rise of emerging powers could create a growing gap between their capacity to act and exert influence on the international stage and our ability to do so.

Of course, investment in defence cannot solve our economic problems. But if we cut defence spending too much, for too long, there is the risk that we could actually make the economic situation worse. Disproportionate defence cuts not only weaken our military forces, but also the industries that support them and which are important drivers for innovation, jobs and exports. This would lead to a dangerous downward spiral of lower growth and smaller and less effective militaries, particularly in Europe.

Governments need to focus on fighting the economic crisis and defence spending cannot be immune as they try to balance their budgets. However, the security challenges of the 21st century – terrorism, proliferation, piracy, cyber warfare, unstable states – will not go away as we focus on fixing our economies. While it is true that there is a price to pay for security, the cost of insecurity can be much higher. Any decisions we take today to cut our defence spending will have an impact on the security of our children and grandchildren.

Hard power will remain essential if we want to keep our populations safe and retain our global influence. This is why NATO Allies must hold the line on defence spending in 2013. We must also do more to get the most out of the funds and resources that we do have; multinational solutions will be vital for minimising our costs and our Alliance will be vital for maximising our capabilities. Then, as soon as our economies improve, we should consider increasing our investment in defence so that we can close the gaps.

For over 60 years, North America and Europe have worked together to protect our freedom, security and well-being. The solidarity of our two continents, embodied in NATO, has led to an unprecedented era of peace and stability. For all these reasons, we must not forget that our values matter, our institutions matter, our way of life matters – and defence matters too.

In 2012, the Allies granted me an additional year as NATO’s Secretary General, extending my tenure to July 2014. Until then, I remain committed to doing all that I can to spread the message that our defence matters, and that NATO matters. My generation was fortunate enough to come of age in a Europe that was free, secure and stable. Together, we must do all that we can to safeguard this precious legacy for future generations on both sides of the Atlantic.

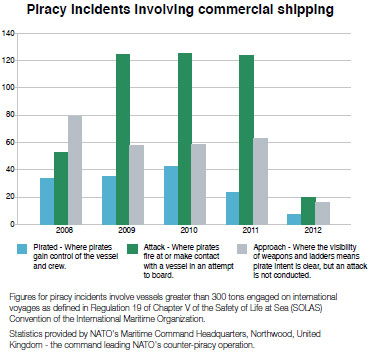

NATO operational priorities

In 2012, the Alliance continued its mission in Afghanistan – the most militarily demanding and significant operational commitment to date. At the same time, the Alliance continued to play a vital role in ensuring a safe and secure environment in Kosovo. It also continued to counter the threat of terrorism in the Mediterranean and play its part in the international community’s efforts to fight piracy off the Horn of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden, where, as a result of those collective efforts, attacks were at an all-time low in 2012. NATO also agreed to augment Turkey’s air defence capabilities by deploying Patriot missiles in order to defend the population and territory of Turkey and contribute to the de-escalation of the crisis along the Alliance’s border.

Today, some 110,000 military personnel are operating in NATO-led missions across three continents.

Afghanistan

NATO Allies and the 22 partner countries contributing to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) are maintaining a steadfast commitment to Afghanistan, with the same fundamental objective that has always underpinned the mission: to ensure that the country never again becomes a safe haven for terrorists.

Transition towards full Afghan security responsibility

Afghan security forces will have full responsibility for security across the country by the end of 2014. This goal was set at the 2010 NATO Summit in Lisbon and confirmed at the Chicago Summit in May 2012. Transition is the process by which responsibility for Afghanistan’s security is gradually transferred to Afghan soldiers and police, while the focus of ISAF’s effort shifts from combat to support. Major progress was made in 2012 with the announcements of more provinces, cities and districts entering the transition process.

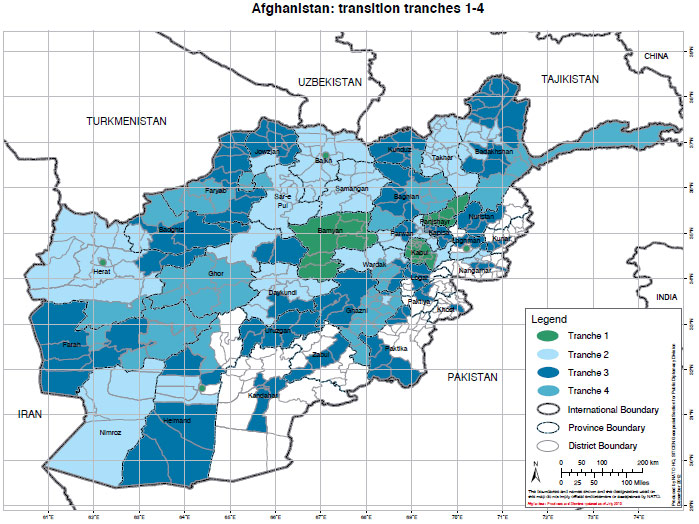

On 22 March 2011, President Karzai announced the first “tranche” of Afghan areas to enter into transition. A second group was announced on 27 November 2011, and a third on 13 May 2012. On 31 December 2012, President Karzai announced the fourth group of Afghan areas to undergo transition in the coming months. With this decision, Afghan security forces will be taking the lead for security for 87 per cent of the Afghan population and for 23 of the 34 Afghan provinces. By mid-2013, every district in Afghanistan will be under Afghan security lead.

Key for transition in Afghanistan is whether security is maintained once the transfer of responsibility from ISAF to Afghan forces is implemented – put simply, whether Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF)1 are able to do the job. Developments over the past year show they can, as areas included in the first two tranches of transition continue to be the most secure in Afghanistan and in some of those areas, security has improved. For example, in the first nine months of 2012, security improved in some of Afghanistan’s most populous districts: the number of insurgent security incidents dropped by 22 per cent in Kabul, 62 per cent in Kandahar, 13 per cent in Herat and 88 per cent in Mazar-i-Sharif. In Regional Command Capital (the area including Kabul), which is the first regional command to have fully entered the transition process, insurgent violence over the months of January to October 2012 dropped by 27 per cent compared to the same period the year before. Throughout 2012, when complex insurgent attacks occurred, including in Kabul, the Afghan security forces took the lead and dealt competently and rapidly with them.

Building ANSF capability

Transition has gathered pace because of the increasing strength, confidence, and capability of the ANSF. Between December 2009 and October 2012, the ANSF grew by more than 140,000 personnel, with the fundamental support provided by the NATO Training Mission- Afghanistan (NTM-A). The ANSF are a credible and capable force, already demonstrating their ability to secure the country and population against the insurgency.

To date, Afghan security forces lead 84 per cent of partnered operations. Overall, they have increased their ability to plan, carry out, and sustain large-scale operations. For example, a series of six large-scale operations were carried out from September to November 2012, involving some 11,000 Afghan security personnel from the Army, border police and intelligence services. And since October 2011, Afghan special forces have conducted more than 4,000 operations, leading 61 per cent of them.

To professionalise the force, NTM-A has provided almost 5,000 trainers in institutions and specialised schools. After graduation, advice and mentoring in the field are then carried on by around 400 ISAF police and military advisory teams deployed around the country.

In 2012, ANSF training efforts emphasised leader development, the training of Afghan trainers, and the building of literacy and vocational skills. Some 3,200 Afghan Army trained instructors deliver 91 per cent of all training across the country and since summer 2012, English language teaching is provided by the Afghan National Army and Afghan Foreign Language Institute. Success in “training the trainers” means that the NTM-A has now been able to start downsizing its own personnel.

While progress has been encouraging, ISAF has faced considerable challenges in 2012. During 2012, there have been a number of attacks against ISAF troops by members of the ANSF or people wearing ANA or ANP uniforms. This is an issue of great concern, which ISAF is taking seriously. ISAF and the Afghan Government have continued working closely together to reduce the risk, for example by improving procedures for the vetting and screening of new recruits; undertaking additional counter-intelligence efforts; and strengthening cultural awareness training for both international and Afghan forces. The effectiveness of these measures is kept constantly under review and further steps will be taken, if needed. Afghan and international troops continue to conduct partnered operations, on a daily basis, across the whole of Afghanistan.

Reinforcing stability

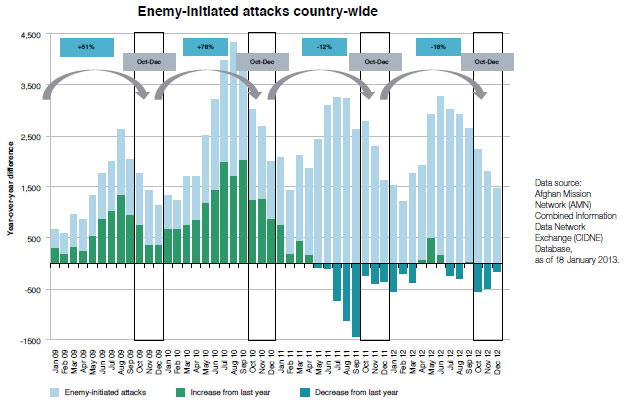

Throughout 2012, the combined efforts of the Afghan National Security Forces and ISAF continued to push insurgents further away from population centres, therefore increasingly isolating them. Eighty per cent of enemy-initiated attacks occur where only 20 per cent of the population lives and nearly 50 per cent of all the attacks country-wide occur in just 17 districts, which only account for 5 per cent of the total Afghan population.

As Afghan security forces become more effective, the insurgents are increasingly targeting civilians. According to the quarterly report of the United Nations Secretary-General published on 6 December 2012, 84 per cent of civilian deaths or injuries were caused by insurgents. Recent surveys indicate that insurgent brutality is widely recognised and condemned by the Afghan population. In some provinces, local residents have been taking up arms and fighting back to reclaim their villages. The insurgency is also eroding from the bottom up, with over 5,600 fighters known to have laid down their arms and rejoined Afghan society through the Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Program, led by the Afghan Government. As support for insurgents decreases, recent surveys indicate that public confidence in the ANSF’s ability to provide security remains high. The general levels of violence throughout the country have dropped over the past two years. While spectacular attacks have grabbed headlines, in the first eight months of 2012, insurgent violence levels country-wide were effectively down by 7 per cent compared to the same period in 2011, and the 2011 figures were down by 9 per cent compared to 2010.

Afghanistan‘s future

The broader international community set out a framework for future support for Afghanistan at the Bonn Conference in December 2011. Nearly half the countries of the world pledged to support a “Decade of Transformation” in Afghanistan, from 2015-2024.

In a strong demonstration of international support, some 60 countries and organisations gathered at a meeting on Afghanistan during NATO’s Summit in Chicago in May 2012. The Lisbon strategy of completing transition to Afghan security lead by the end of 2014 was reaffirmed. Allied leaders agreed that NATO’s main contribution to Afghanistan after 2014 will be to continue training, advising and assisting the ANSF through a significantly smaller, non-combat mission that will follow on from ISAF.

NATO Allies and ISAF partners reaffirmed their strong commitment to support the training, equipping, financing and capability development of the ANSF beyond the end of the transition period. At the meeting of ISAF foreign ministers in Brussels in December 2012, it was decided that the existing Afghan National Army Trust Fund will be further adapted to support the sustainment of the Afghan forces post-2014. The ANA Trust Fund will complement the broader international efforts and other funding streams under a robust accountability framework. The lead responsibility for sustaining Afghan security forces rests with the Afghan Government. Funding mechanisms for the sustainment of the ANSF post-2014 will be based on Afghan leadership and ownership of the whole process.

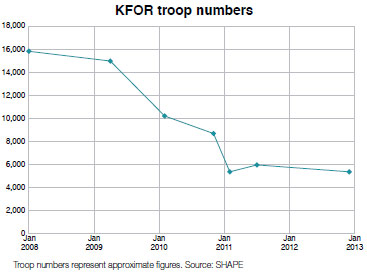

Kosovo

KFOR’s objective in 2012 was to continue to support the development of a peaceful, stable, and multi-ethnic Kosovo. This NATO-led force also continued to support the maintenance of freedom of movement and ensuring a safe and secure environment for all people in Kosovo, in cooperation with all relevant actors. After a difficult year in 2011 with a number of serious incidents, the situation in Kosovo improved in 2012 thanks to KFOR's sustained efforts, in close cooperation with the European Union’s Rule of Law Mission (EULEX), and with the support of all communities in Kosovo.

Kosovo reached an important milestone with the end of supervised independence on 10 September 2012. But corruption, organised crime and the lack of economic development continue to influence the general security situation, particularly in the northern part of Kosovo. KFOR maintained its Operational Reserve Force in Kosovo throughout the year to be able to respond swiftly to possible incidents and ensure freedom of movement. However, improvements in the security situation on the ground prompted the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) into withdrawing this reserve force at the end of 2012. NATO will consider further troop downsizing only when the situation on the ground allows.

In parallel, to acknowledge further progress in handing over security responsibilities to local authorities, KFOR “unfixed” the Devič Monastery, a cultural and religious site with designated special status. The “unfixing” process involves the transfer of responsibility for the protection of a religious or cultural site of particular symbolic value, from KFOR to the Kosovo Police. From the original nine KFOR-protected sites in Kosovo, only two such sites, the Peć Patriarchate and the Dečani Monastery, remain under direct KFOR protection and are likely to be transferred in the near future. The Peć Patriarchate should be the next site to be “unfixed” in 2013.

During 2012, NATO continued its support to the Kosovo Security Force (KSF). The KSF is a lightly armed force which will be responsible for security tasks that are not appropriate for the police such as emergency response, fire fighting and civil protection. Following the declaration of full operational capability for the KSF in 2013, the scope and size of NATO’s support will be adjusted.

Meanwhile, progress has been achieved in the EU-sponsored Dialogue between Belgrade and Priština, in particular on Integrated Border Management. This dialogue for the normalisation of relations between Serbia and Kosovo remains key to solve the political deadlock over northern Kosovo.

Counter-piracy

Piracy is still threatening the security of maritime routes off the Horn of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden, but has diminished considerably compared to previous years.

The presence of an international naval force in the region has contributed to this result. NATO (with Operation Ocean Shield) together with other international actors, notably the European Union (with Operation Atalanta) and the US-led Combined Maritime Forces, have steadily maintained a deterrence presence in the region. This has helped to deter and disrupt pirate attacks, and protect vessels.

In March 2012, NATO members took stock of the situation through a “strategic assessment”, agreeing more robust actions against piracy. Measures introduced included the need to erode the pirates’ logistics and support base by, for instance, disabling pirate vessels or skiffs, attaching tracking beacons to mother ships and allowing the use of force to disable or destroy suspected pirate vessels. NATO has also extended its counter-piracy operation until at least the end of 2014.

The progress made in 2012 needs to be consolidated in the medium to long term. A deterrence presence, however effective and necessary in the short term, cannot bring a lasting solution to the problem of piracy. The countries in the region, including Somalia, need to develop the capacity to fight piracy themselves. During 2012, NATO offered capacity-building support, for example during port visits which have included the training of coast guards. NATO is also helping to fight the root problem of piracy onshore by continuing to support the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), at the African Union’s request, in terms of sea- and airlift and also with the provision of subject-matter experts on the ground.

Operation Ocean Shield has contributed to the international effort in the Gulf of Aden and off the Horn of Africa since 2008, allowing the safe transit of humanitarian supplies to Somalia. This has also helped increase the safety of one of the busiest maritime routes in the world – the gateway in and out of the Suez Canal. With 90 per cent of world trade transiting by sea (representing 23 per cent of the world’s Gross Domestic Product), the security of sea lanes is essential.

NATO support to Turkey

The situation along NATO’s south-eastern border and repeated violations of Turkey’s territory led to a request from Turkey for Alliance support in the second half of 2012.

In June, following the shooting down of a Turkish jet, Turkey requested that the North Atlantic Council discuss the security situation in the region under Article 4 of the Washington Treaty. In October, following the death of five civilians after Syrian shells hit the Turkish town of Akçakale, tensions rose further, leading Turkey to request Alliance support to augment its air defence capabilities.

On 4 December, NATO foreign ministers agreed to deploy Patriot missiles to help defend the population and territory of Turkey and contribute to the de-escalation of the crisis along the Alliance’s border. Germany, the Netherlands and the United States agreed to provide two Patriot missile batteries each, which will be sited at Kahramanmaraş, Adana and Gaziantep. This deployment will be defensive only and will not support a no-fly zone or any offensive operation.

Securing capabilities for the future

Central to the Alliance’s ability to conduct operations are military capabilities – the people, equipment, training, command and support arrangements – organised and trained to act when called upon. Over the past decade, these military capabilities have been in great demand. With a change in NATO’s military commitment to Afghanistan after 2014, as a significantly smaller, non-combat mission takes over from ISAF, NATO’s focus will shift to ensuring the Alliance has the types of capabilities needed to face the security challenges of the future.

At the Chicago Summit, Allied leaders agreed on how best to prepare for future security challenges which could also include non-conventional threats, such as cyber attacks. The objective of the Chicago Defence Package was to have a coherent set of deployable, interoperable and sustainable forces that are equipped, trained, exercised and commanded so as to be able to meet the objectives the Alliance has set itself: “NATO Forces 2020”.

Against a background of economic austerity, delivering NATO Forces 2020 will only be possible if the Allies spend smarter. This means spending more efficiently, including through more multinational cooperation, and spending more effectively, including through making sure that their militaries retain their ability to operate together as they have done on NATO-led missions.

Challenging economic circumstances

In the current economic climate, with public expenditure decreasing across the board, NATO Allies have been increasingly challenged to find the necessary financial resources to ensure they can maintain the appropriate military capabilities. Defence budgets in most countries have declined at a time when the Alliance has undertaken its most demanding and significant mission ever, and when the need for investment in future capabilities is essential.

The positive news is that the Alliance, as a whole, does have a pool of forces and capabilities sufficient to conduct the full range of its missions. But the effects of the financial crisis and the declining share of resources devoted to defence in many Allied countries have resulted in an over-reliance on a few countries, especially the United States, growing capability disparities among European Allies, and some significant deficiencies in key capabilities, such as intelligence and reconnaissance, as illustrated by NATO’s experience in Libya. In 2012, with the approval of the Defence Package and key initiatives such as Smart Defence and Connected Forces, Allies have started to take steps toward addressing these issues.

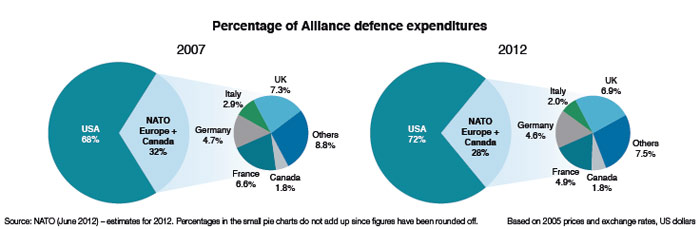

The combined wealth of the non-US Allies, measured in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), exceeds that of the United States. However, non-US Allies together spend less than half of what the United States spends on defence, and in the decade since 2001 – the year of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States – their annual increases in defence spending have been significantly less. Since 2008, defence spending by most non-US Allies has declined steadily.

The pie charts show that the United States’ share of Alliance defence spending2 has increased from 2007 to 2012. While France, Germany and the United Kingdom together represent more than 50 per cent of the non- US Allies defence spending, more recently their defence spending has come under increasing pressure. The share of the other European Allies together has fallen from 8.8 to 7.5 per cent.

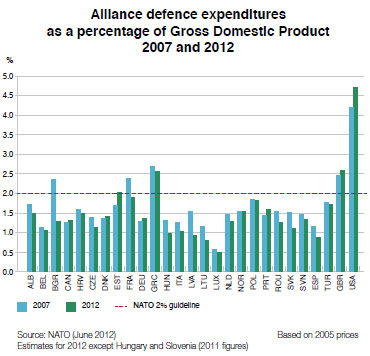

In 2006, Allies agreed to commit a minimum of two per cent, as a percentage of GDP, to spending on defence. The graph below shows how Allies are performing against this NATO two per cent guideline. In 2007, only five Allies spent more than two per cent; in 2012 this number had declined to four.

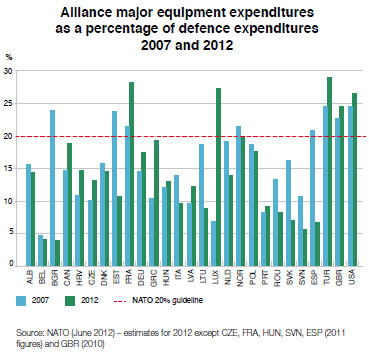

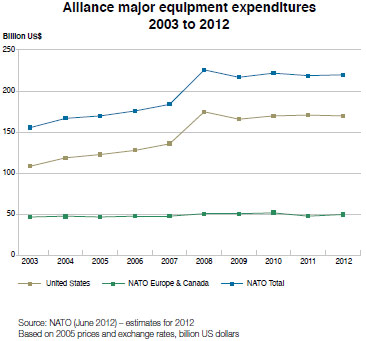

Alongside the two per cent guideline, it is also important to consider what the resources are actually devoted to, from an Alliance perspective. Allies have agreed that at least 20 per cent of defence expenditures should be devoted to major equipment spending,3 a crucial indicator for the pace of modernisation. The graph below shows that in 2012 only five Allies spent more than 20 per cent of their defence budgets on major equipment expenditure; among the 22 Allies that spent under 20 per cent in critical investment in future capabilities, nine Allies spent less than ten per cent.

Nevertheless, as shown by the next graph, the investment across the Alliance as a whole in major equipment has risen from 2003 to 2012, mainly as a result of increases in spending by the United States. Taken together, investment in major equipment by the non-US Allies has held steady – some countries have increased their investment and others have decreased.

The result of these disparities in investment is two-fold: an ever greater military reliance on the United States, and growing asymmetries in capability among European Allies. This has the potential to undermine Alliance solidarity and puts at risk the ability of the European Allies to act without the involvement of the United States. Cuts in European equipment procurement could also weaken Europe’s defence industrial base and the ability of European armed forces to remain at the cutting edge of technology.

Yet the contribution of individual Allies is not measured by defence expenditure alone. While NATO’s operation in Afghanistan has absorbed a large proportion of the Allies’ capabilities for a decade, it has also driven the modernisation of their forces. Moreover, other outstanding NATO commitments have been maintained, and principally by non-US Allies. The NATO-led operation in Kosovo, air policing and air defence of NATO’s airspace, NATO’s four standing maritime forces, and the Alliance’s high-readiness standby force (the NATO Response Force or NRF) had to be sustained with a continuous provision of forces.

There is also a third impact of declining defence expenditure within the Alliance. Looking beyond the Alliance to defence expenditures worldwide reveals that NATO’s accumulated defence spending continues to be the highest in the world. However, while in 2011 NATO still represented 60 per cent of global defence spending, the trend is steadily downward from 69 per cent in 2003. NATO’s share remains pre-eminent but may fall to 56 per cent or lower, as early as 2014, if current defence spending patterns among NATO members and other countries worldwide persist.

Together, these three gaps could gradually compromise the Alliance’s ability to contribute to international crisis management efforts and cooperative security initiatives. Addressing these gaps has been at the centre of the Alliance’s work in 2012.

“NATO Forces 2020”

NATO needs to continue ensuring that it has all the capabilities it needs to fulfil the full range of its tasks and missions. At the Chicago Summit in May 2012, NATO leaders set the Alliance an ambitious but realistic goal: NATO Forces 2020. The objective is to have a coherent set of deployable, interoperable and sustainable forces that are equipped, trained, exercised and commanded so as to be able to meet the targets the Alliance has set itself. These Allied forces should be able to operate together, and with partners, in any environment.

Over time, Allies have made strenuous efforts to enhance the effectiveness of their contributions to NATO operations. The requirement to sustain NATO’s engagement in Afghanistan, in particular, has had a positive impact on the overall capacity of Allies to deploy and sustain an increasingly large portion of their forces at a distance from their home locations. Today, NATO as well as partner forces are much better prepared to conduct complex expeditionary operations in a challenging, unfamiliar environment. Of the 23 European Allies with armed forces, the large majority of them increased the deployability and sustainability of their land forces (18 and 17 Allies respectively) by 2010. Indeed, those 23 European Allies collectively generated 110,000 more deployable land forces in 2010 than in 2004, representing an increase of over 25 per cent. Increases in sustainable land forces over the same period were equally significant.

These improvements result from a range of measures aimed at increasing the mobility and sustainability of land forces and expanding airlift and sealift capacity to transport them on an increasingly large scale; improving the capacity of tactical fighter aircraft to deploy to, and operate from, distant airfields in austere operational conditions; and enlarging the operating area of many Allied navies.

As a result, Alliance forces today bear little resemblance to the NATO forces of two decades ago. In most cases, the armour-heavy national army corps that stood guard during the Cold War have been succeeded by multinational, rapid reaction corps combining a mix of heavier and lighter forces. Many Allied air force squadrons that were tied logistically to their home air bases are now able to deploy within days to other countries – as during Operation Unified Protector in 2011 from Belgium, Denmark, The Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom to NATO airfields in France, Greece, Italy and Spain – or to another continent, from Europe to Afghanistan. For the first time ever, Allied navies are operating under NATO command routinely in the western Indian Ocean as part of wider international counter-piracy efforts. The experience gained has shown that individual armed services need to maintain, or strive for, a satisfactory balance between frontline combat forces – whether land, air or maritime – and the supporting assets that enable them to operate.

The foundations for NATO Forces 2020 are, therefore, in place, but must be protected at a time of unprecedented fiscal challenge. To that end, NATO is introducing a reinforced culture of cooperation through Smart Defence and the Connected Forces Initiative and is continuing to pursue NATO-wide reforms to create leaner and more effective structures.

Smart Defence

Smart Defence is a new mindset, enabling countries to work together to develop and maintain capabilities they could not afford to develop or procure alone, and to free resources for developing other capabilities.

At the Chicago Summit, Allies agreed to take forward an initial package of 22 Smart Defence projects, which will deliver improved operational effectiveness, economies of scale and closer connections between NATO forces. The experience gained through these projects is expected to help build confidence in multinational cooperation on the larger-scale capabilities required by the Alliance. These projects include:

NATO Universal Armaments Interface: a technical solution enabling different fighter jets to use munitions from various sources and countries, in order to facilitate the flexible use of munitions across the Alliance. The 2011 air operation over Libya demonstrated the importance of such a project.

Maritime Patrol Aircraft: a multinational pool of maritime patrol aircraft, available to all the participating countries, and upon request to others as well, for a more flexible and efficient use of available assets.

Multinational Medical Treatment Facilities: standardized modular medical facilities for multinational deployments in support of operations, which will allow countries to make the best possible use of medical assets.

Deployable Air Activation Modules: a deployable air base will be created by pooling components required for deployable airfields in support of operations. These deployable airfields are called deployable air activation modules. The multinational pool of deployable air activation modules will be built from capabilities made available by various countries.

Since the Chicago Summit, Smart Defence has already produced several more projects. For these positive results to achieve lasting success, all stakeholders, including defence industry, adopt the Smart Defence mindset and actively promote defence cooperation. European Allies are involved in every single one of the 25 Smart Defence projects agreed so far and are leading around two-thirds of them. In fact, one third are purely European in terms of participation.

In addition to these Smart Defence projects, the Alliance is engaged in the implementation of three multinational programmes that have particular significance – missile defence, Alliance Ground Surveillance and Joint Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance. These programmes aim to provide NATO with a state-of-the-art collective military capacity to meet emerging security threats and fill outstanding operational needs.

Missile defence

NATO remains concerned by the increasing threat posed by the proliferation of ballistic missiles, which could carry conventional as well as chemical or nuclear warheads. Building on the theatre missile defence programme aimed at protecting deployed troops, NATO leaders decided at the 2010 Lisbon Summit to expand this programme to provide full coverage and protection for all NATO European populations and territory. At the 2012 Chicago Summit, NATO leaders took a significant first step towards this goal by declaring an interim NATO ballistic missile defence capability that now offers the maximum coverage, within available means, to defend populations, territory and forces for NATO countries in Southern Europe.

NATO is working intensively to enhance its command and control arrangements, accommodating national contributions such as the US forward-based radar, US Aegis surface ships with a ballistic missile defence capability operating in the Mediterranean, as well as several assets proposed by other Allies.

At the Chicago Summit, NATO leaders also repeated their commitment to cooperate with Russia on missile defence. They reiterated that NATO’s missile defence programme in Europe is not directed against Russia and will not undermine Russia’s strategic deterrence capabilities. They also proposed to Russia to establish two joint centres for missile defence, related to data fusion and to planning operations, and to develop a transparency regime on missile defence. Work on theatre missile defence cooperation dominated discussions and activities in 2012. In March, a NATO-Russia Council computer-assisted exercise was held in Germany, with experts from Russia and NATO countries, demonstrating that cooperation is not only possible but would also be mutually beneficial. However, more progress is needed to ensure that missile defence cooperation with Russia can reach its full potential.

Alliance Ground Surveillance

The NATO-led operation in Libya showed the importance of an airborne ground surveillance and reconnaissance capability to provide commanders a comprehensive picture of the situation in the field. For the NATO-owned and -operated Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) programme, 2012 has been a landmark year. On 20 May, in the margins of the Chicago Summit, a procurement contract was signed for the delivery of this capability.

While the initial core capability of five Global Hawk unmanned aerial vehicles and associated systems is being procured by 13 participating countries, on 3 February 2012 the North Atlantic Council also agreed that NATO common funding will be engaged and utilised towards AGS infrastructure and satellite communications, as well as operations and support once the system becomes fully operational in 2017. Contributions in kind provided by France and the United Kingdom will complement AGS with additional surveillance systems.

This new capability will be a key component of a wider Joint Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR) capacity aimed at providing the Alliance collectively with an improved situational awareness of its security environment in support of deterrence, defence and crisis management.

Joint Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR)

Providing “the right information to the right person at the right time” during a military operation is a challenging task. In 2012, a new JISR initiative was launched to help coordinate the gathering, analysis and dissemination of information. It will use information gathered by the Alliance Ground Surveillance system and other ISR assets in support of Alliance operations, integrating operations and intelligence.

This will permit the coordinated collection, processing, dissemination and sharing within NATO of ISR material, in direct support of current and future operations.

Based upon a proposal in April by eight Allies to rectify shortfalls in the JISR domain identified during operations in Afghanistan and Libya, an enduring NATO JISR capability was subsequently affirmed at the Chicago Summit as one of the Alliance’s most critical capability needs. In June, a technical trial was organised in Norway to test the connectivity of surveillance systems from 17 Allies. The findings of this trial are guiding further work on the JISR initiative that will be pursued into 2013.

The Connected Forces Initiative

The experience of operating together in Afghanistan in a demanding environment has built strong ties of interoperability and common purpose among Allies and non-NATO troop contributors. After 2014, once the ISAF mission is completed, it will be important to maintain this culture.

The Connected Forces Initiative (CFI) aims to ensure the ability of forces to be able to communicate and work with each other. At the most basic level, this implies individuals understanding each other and, at a higher level, the use of common doctrines, concepts and procedures, as well as interoperable equipment. Forces also need to increasingly practice working together through joint and combined training and exercising, after which they need to standardize skills and make better use of technology. All three aspects – communication, practice and validation – constitute the different facets of CFI. The area of C4 (Command, Control, Communications and Computers) Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR), which provides the glue that binds NATO forces together, is at the forefront of this work. The Connected Forces Initiative also seeks to make greater use of education, training and exercises to reinforce links between the forces of NATO member countries and maintain the level of interoperability needed for future operations.

Reform NATO-wide

Reform of internal structures is an intrinsic part of the Alliance’s ongoing transformation. In 2012, the focus was on the reform of NATO agencies and the International Staff and International Military Staff. In parallel, the implementation of the reform of the military command structure continued.

The aim of the Agencies Reform, approved in June 2011, was to improve governance, effectiveness and efficiency of the services and programmes of the NATO agencies and, ultimately, to achieve savings. NATO agencies provide critical support to operations and managing the procurement of major capabilities. As a consequence, the rationalisation and consolidation of their existing functions, services and programmes into a new structure feeds into the Smart Defence initiative – more interoperable and cost-effective defence capabilities through smarter spending and enhanced cooperation.

In July 2012, in line with the reform implementation plan, the North Atlantic Council established four new NATO organisations to integrate responsibilities of the former agencies: communications and information, support, procurement and science and technology. The restructuring process will be executed in three phases over the coming two years by initially consolidating and then gradually optimising all elements that will be assumed by the new organisations. Transition measures have been put into place to ensure full continuity in service and capabilities delivery.

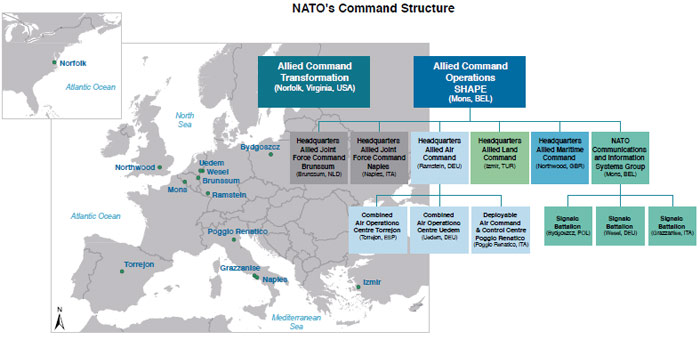

Implementation of the new, streamlined command structure, agreed in June 2011, took place on 1 December 2012. NATO’s Command Structure has been downsized from 11 to seven entities,4 with a 33 per cent reduction in posts.5 The new command structure is illustrated below.

As planned, the collocation of the International Staff and the International Military Staff at NATO Headquarters in Brussels was completed mid-2012 to improve internal working arrangements. Discussions on the overall reform of the International Staff continued with the ultimate goal of evolving towards a leaner, more flexible workforce sharply focused on NATO’s priority areas, in time for the move to the new NATO Headquarters in 2016. There have already been significant reductions in support staff in the current organisation and work is being pursued to identify further efficiency savings. At the same time, a review of the International Military Staff has been put in train. NATO also reviewed its financial procedures in 2012 and identified a number of measures to improve accountability, transparency and effectiveness.

Emerging security challenges

In 2012, NATO continued to develop a substantive role in dealing with emerging security challenges, moving from policy to the implementation of concrete plans and activities.

Cyber defence

NATO has continued to implement its new cyber defence policy through a comprehensive and ambitious action plan launched in October 2011. In the spring of 2012, NATO concluded an important contract for 58 million Euros with a consortium of private companies to significantly upgrade its unique operational cyber defence capability, the NATO Computer Incident Response Capability (NCIRC).

When this project is completed in the autumn of 2013 and all NATO networks are brought under centralised protection, NATO’s ability to defend its military and civilian networks against all types of intrusion and attack will be greatly enhanced. NATO will also be in a better position to assist Allies and partners to detect, defend against and recover from cyber attacks, and to deploy Rapid Reaction Teams upon request. To further enhance its cyber defence capabilities, NATO established a cyber threat assessment cell and held its first full-scale crisis management exercise based on a cyber defence scenario. Another annual exercise, known as “Cyber Coalition”, was also held. It involved both Allies and partners, and proved its worth in testing incident response and crisis management procedures.

Counter-terrorism

The Chicago Summit endorsed an updated set of guidelines for NATO’s counter-terrorism strategy and a concrete action plan will be adopted in 2013. The Defence Against Terrorism Programme of Work has organised exercises, field trials and demonstrations which have helped Allies to agree common standards for route clearance, countering improvised explosive devices and disposing of explosives safely. NATO-Russia cooperation has moved ahead on the STANDEX project to safeguard mass transit systems in major cities against terrorist attacks; and NATO and Russia have organised counter-terrorism exercises and increased their exchange of information and experience in responding to the threat of terrorism. In the area of protection against chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear substances, NATO has focussed particularly on the maritime dimension and the boarding and inspection of ships suspected to carry these materials.

The Deterrence and Defence Posture Review

One of the key outcomes of the Chicago Summit was the Deterrence and Defence Posture Review. It examined in depth NATO’s ability to ensure its defence and deterrence capacity against a broad range of 21st century threats. The Review commits NATO to maintain an appropriate mix of nuclear, conventional and missile defence capabilities for deterrence and defence to fulfil its commitments, as set out in the 2010 Strategic Concept. It also stipulates that Allies will continue to support arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation efforts.

The Review reaffirmed that NATO will remain a nuclear alliance as long as nuclear weapons exist – and that all components of NATO’s nuclear deterrent remain safe, secure, and effective. Allies agreed to develop concepts to ensure the broadest participation in nuclear sharing arrangements, including in case NATO were to decide to reduce its reliance on non-strategic nuclear weapons based in Europe. Moreover, the Review stated that NATO will explore reciprocal transparency measures with Russia to facilitate a nuclear deterrence posture at the lowest levels commensurate with Allied security.

Extending partnerships

At a time of complex and unpredictable global risks and threats, delivering security must be a cooperative effort. NATO continues to strengthen its connections with other countries and organisations around the globe, reflecting the commitment to cooperative security outlined in the 2010 Strategic Concept.

In 2012, the Alliance has sought to broaden its partnerships and reinforce existing ones which could make a concrete contribution to the success of the Alliance's fundamental tasks.

A broader range of partners

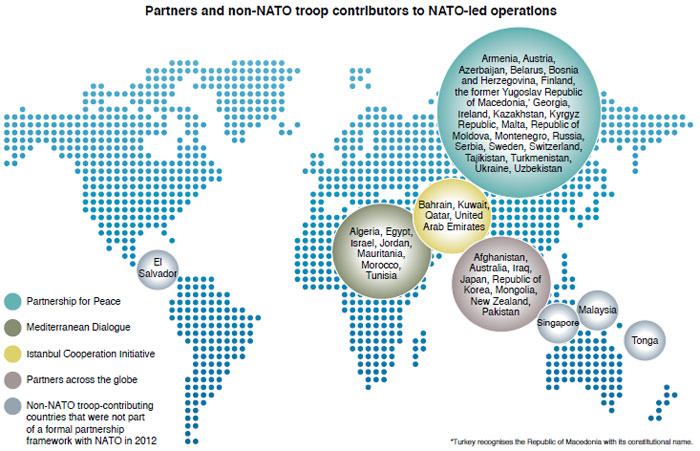

Over the past two decades, NATO has developed a network of structured partnerships with countries across the Euro-Atlantic area, the Mediterranean and the Gulf region, as well as with other international organisations. Building on these formal partnerships, it has reached out to other partners across the globe, with which it engages in individual relationships.

Many NATO partners have made particular political, operational and financial contributions to NATO-led operations. In recognition of that, at the Chicago Summit in May 2012, NATO Allies held a meeting with the leaders of a group of 13 partner countries – Australia, Austria, Finland, Georgia, Japan, Jordan, the Republic of Korea, Morocco, New Zealand, Qatar, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Arab Emirates.

In June, NATO and Australia signed a joint political declaration reflecting their ever-stronger ties and their determination to deepen cooperation to meet common threats. This bilateral agreement is soon to be complemented by an Individual Partnership Cooperation Programme covering existing cooperation and outlining priority areas for future cooperation. Iraq, Mongolia, New Zealand and the Republic of Korea also engaged in Individual Partnership Cooperation Programmes with NATO for the first time in 2012.

The full scope of NATO's broadened relations with different countries is captured in the illustration on the previous page.

Cooperation between NATO and Russia continues to be of strategic importance, as NATO and Russia share common security interests and face common challenges. Cooperation on Afghanistan has deepened, with an expansion of Russia’s support for NATO transit requirements for the ISAF mission, training of counternarcotics officials and maintenance of Afghan army helicopters. In the field of cooperative airspace, NATO Allies and Russia have developed an initiative which allows neighbouring countries to monitor civil aircraft suspected of being hijacked by terrorists. This system reached its operational capability in December 2011. A simulated exercise called “Vigilant Skies 2012” took place on 13-14 November 2012 to test procedures and capabilities.

The Alliance’s other formal partnerships also progressed in 2012. NATO is working towards agreeing a new political framework for the Mediterranean Dialogue to reinforce the existing relationship between the NATO Allies and the seven partner countries which participate in this initiative. Kuwait generously agreed to host an Istanbul Cooperation Initiative Centre, which will help NATO deepen relations with all of its Gulf partners.

Relations with international organisations are developing at a steady pace. NATO and the United Nations enhanced high-level contacts in 2012. NATO and European Union personnel serve side by side in Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Afghanistan. Regular staff-level contacts are held to exchange information and avoid duplication, particularly in the area of capability development. NATO also maintains regular contacts with the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and has continued to explore the possibilities for further cooperation with the African Union and other regional organisations.

Working closely with operational partners

One of NATO's most important partnership achievements has been to develop the expertise for NATO and partner militaries to be able to work together and implement complex joint operations. Allies remain committed to giving operational partners a structural role in shaping strategy and decisions, from the planning through to the execution phase, of current and future NATO-led operations to which they contribute. This has been the case for the 50-nation ISAF mission and the Libya operation. It is now also taking place for the planning of the post-2014 NATO-led mission in Afghanistan, where countries that have declared their willingness to commit to a concrete and substantial contribution are already part of the planning.

Greater cooperation in tackling security challenges

NATO is also stepping up its engagement with partners in new areas, such as cyber security and energy security. In 2012, partners participated in the annual cyber defence exercise aimed at testing incident response and crisis management procedures. Additionally, partner participation is also growing in the area of defence institution building. The Building Integrity Programme provides tailored support to Afghanistan and countries in South Eastern Europe to help reduce the risk of corruption in the defence sector. By promoting good practice and providing practical tools, the programme is helping to strengthen transparency, accountability and ultimately, to make financial savings.

Education is a key agent of transformation and NATO is using it to support institutional reform in partner countries. The Alliance’s education and training programmes, which initially focused on increasing interoperability between NATO and partner forces, have been expanded. They now also provide a means for Allies and partners to collaborate on how to build, develop and reform educational institutions in the security, defence and military domain. Defence education enhancement programmes have been set up with Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan and the Republic of Moldova. In 2012, Iraq and Mauritania also began cooperating in this field with NATO, while Ukraine and Uzbekistan have requested assistance.

Maintaining an open door policy

At the Chicago Summit, NATO met with the four partners that aspire to NATO membership – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Montenegro and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia6 – and reiterated its commitment to taking in new members. NATO will continue work with all four to pursue the reforms necessary to meet Alliance standards.

Footnotes:

- The Afghan National Security Forces consist of the Afghan National Army (ANA) and the Afghan National Police (ANP).

- For all of the graphs in this chapter of the report, it should be noted that Albania and Croatia joined the Alliance in 2009 and that Iceland has no armed forces.

- Major equipment spending includes research and development spending devoted to major equipment.

- These figures cover Allied Command Operations (ACO) and Allied Command Transformation (ACT).

- This percentage covers the entire Command Structure: ACO, ACT and the NATO Communication and Information Systems Services Agency.

- Turkey recognises the Republic of Macedonia with its constitutional name.