Secretary General’s Annual Report 2011

- English

- French

Foreword

Many will remember 2011 as a year of austerity. But it has also been a year of hope. The international community united in its responsibility to protect. Much of the Arab world took a new path forward. And the European Allies showed they were willing and able to lead a new NATO operation.

For NATO, 2011 was one of the busiest years ever. From Libya to Afghanistan and Kosovo, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean, the Alliance was committed to protecting its populations and active in upholding its principles and values. We enabled the Afghan security forces to start taking the lead for security for over half of the Afghan population. We successfully concluded our training mission which has contributed to improving Iraq’s security capacity. 2011 was also a benchmark year for reforms. We took significant steps to further streamline our structures, enhance our effectiveness and reduce our costs. At the same time, we strengthened our capabilities in many areas, including the prevention of cyber attacks. And we enhanced our connectivity by increasing cooperation with our partner countries in the Euro-Atlantic area, the Middle East, North Africa and the Gulf, as well as with many other countries across the globe. This is a transatlantic Alliance that, despite the economic crisis, has once again demonstrated its commitment, capability and connectivity.

In 2011, our new Strategic Concept was put to the test. This report – the first of its kind – shows that we successfully met that test.

At the start of the year, few would have imagined NATO would be called to protect the people of Libya. But on 31 March, NATO took swift action on the basis of the historic United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973. We saved countless lives. And seven months later, we successfully completed our mission. When I visited Tripoli on 31 October, Chairman Jalil of the National Transitional Council told me, “NATO is in the heart of the Libyan people.”

Operation Unified Protector was one of the most remarkable in NATO’s history. It showed the Alliance’s strength and flexibility. European Allies and Canada took the lead; the United States provided critical capabilities; and the NATO command structure unified all those contributions, as well as those of our partners, for one clear goal. In fact, the operation opened a completely new chapter of cooperation with our partners in the region, who called for NATO to act and then contributed actively. It was also an exemplary mission of cooperation and consultation with other organizations, including the United Nations, the League of Arab States, and the European Union. Throughout, NATO proved itself as a force for good and the ultimate force multiplier.

These achievements give me great confidence as I look forward to 2012. Clearly, economic challenges are likely to remain a dominant factor and decisions taken today may shape our world for decades to come. Our task is to make sure we emerge stronger, not weaker, from the crisis we all face. But we can draw great strength from an enduring source: the indivisibility of security between North America and Europe. NATO is a security investment that has stood the test of time for over six decades and continues to deliver real returns for all Allies, year after year.

2012 will be marked by our Chicago Summit in May. This will be an opportunity to renew our commitment to the vital transatlantic bond between us and to redouble our efforts to share the burden of security more effectively. We will take important decisions to keep NATO committed, capable and connected.

Afghanistan remains by far our largest operation, with over 130,000 troops as part of the broadest coalition in history. 50 Allies and partners are determined to ensure the country will never again be a base for global terrorism. Afghanistan is moving into the right direction and transition to Afghan security lead is on track to be completed by the end of 2014. As Afghan security forces grow more confident and capable, our role will continue to evolve into one of support, training and mentoring. But the Chicago Summit will show our commitment to a long-term partnership with Afghanistan, together with the whole international community, beyond 2014.

At Chicago, we will also take measures to improve our capabilities. During our operation in Libya, the United States deployed critical assets, such as drones, precision-guided munitions and air-to-air refuelling. We need such assets to be available more widely among Allies. In the current economic climate, delivering these expensive capabilities will not be easy. But it can be done, and it is critical if we are to respond effectively to the challenges of the future. The answer lies in what I call “smart defence”: doing better with less by working more together. In Chicago, we will deliver real “smart defence” commitments, so that every Ally can contribute to an even more capable Alliance.

NATO’s missile defence system to defend European Allies’ populations, territory and forces against the growing threat of ballistic missile proliferation is “smart defence” at its best and it embodies transatlantic solidarity. We have already made considerable progress. Along with a prominent and phased US contribution, a number of Allies have made significant announcements, including Turkey, Poland, Romania, Spain, the Netherlands and France. These different national contributions will be gradually brought together under a common NATO command and control system. Key elements of it have already been tested successfully and I expect the initial components of the system to be in place by the time of the Chicago Summit.

NATO has invested heavily in its network of partnerships. Continued NATO-Russia cooperation is vital for the security of the Euro-Atlantic area and the wider world. Twenty-two partner countries have troops or trainers on the ground in Afghanistan. And our successful operation to protect the people of Libya could not have taken place without the political and operational support of our partners in the region and beyond. At Chicago, we will recognize the contribution made by our partners who are willing and able to share the security burden with us.

Chicago is about delivering important commitments. Personal commitment, too, has been key to the Alliance’s success. Dedicated civilian and military staff are working in operational theatres and in headquarters to protect our 900 million citizens. They work under demanding and dangerous conditions. This report is a tribute above all to their sacrifice, bravery, and professionalism.

Anders Fogh Rasmussen

NATO Secretary General

NATO operations – progress and prospects

The tempo and diversity of NATO operations have increased considerably since the Alliance’s first military interventions in the early 1990’s. Today, over 140,000 military personnel are engaged in NATO-led missions on three continents, managing complex ground, air and naval operations in all types of environment.

Afghanistan constitutes the Alliance’s most significant operational commitment to date. 2011 was, however, marked by NATO’s commitment to Libya, which showed that the Alliance is prepared, equipped and able to intervene in such crises – and must continue to be able to do so.

NATO is also helping to provide peace and security in Kosovo, and is playing a key role in the stability of the entire Western Balkans region. Off the Horn of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden, the Alliance is making a significant contribution to counter-piracy efforts, helping to protect a vital waterway through to Europe and the East for the global economy.

Afghanistan

The main focus of the UN-mandated, NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) remains the provision of security for Afghanistan. ISAF conducts security operations in coordination with the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and assists in the development of Afghan National Security Forces and structures, including training the Afghan National Army and the Afghan National Police. Currently, more than a quarter of the world’s countries are participating in ISAF – a true measure of the unwavering international commitment to Afghanistan’s secure, stable and democratic future.

The fundamental reason for ISAF’s presence is to ensure that the country never again becomes a safe haven for terrorists.

2011 has been a year of consolidation, reinforcing the achievements made in 2010 with ISAF’s counter-insurgency strategy, especially in the south of the country, and commencing the gradual transition of responsibility for the security of the country from ISAF troops to Afghan forces. In 2011, over half the population saw their army and police beginning to take the lead in providing them with security. In addition to conducting security operations, ISAF has continued to help build up the Afghan army and police force through the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan (NTM-A). In parallel,

ISAF is also directly involved in facilitating the development and reconstruction of Afghanistan through Provincial Reconstruction Teams throughout the country.

Over time, greater stability has enabled progress on all fronts. Access to basic healthcare is improving and infant mortality is falling; school enrolment of children – including girls – has increased from under 1 million in 2001 to around 8 million in 20111; and 5.7 million refugees have returned from Pakistan and Iran, representing nearly a quarter of Afghanistan's population2.

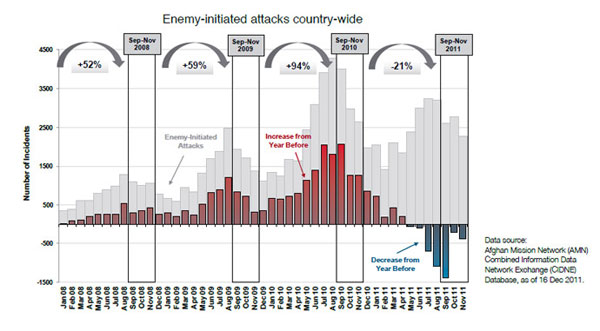

Stability continues to improve. In 2011, overall enemy-initiated attacks decreased and the insurgency was weakened.

Indeed, attacks were down 8 per cent country-wide compared to 2010. In Helmand, attacks decreased by 30 per cent and in some districts by 80 per cent. While spectacular attacks dominate the media, the insurgency has declined, rather than intensified. Combined Afghan National Security Forces and ISAF-led operations placed persistent pressure on the insurgency, in areas such as the South, where it was at its strongest.

Despite this momentum, much work remains to be done. Insurgents continue to conduct high-profile attacks and intimidation campaigns. They have targeted high-ranking government officials as well as influential political and religious leaders.

Transition: ‘A new era of stability, security and responsibility for Afghanistan’

Progress in Afghanistan, in particular with regard to the training of the Afghan army and police force, has enabled the start of transition to full Afghan security lead. Transition is the process by which responsibility for Afghanistan’s security is gradually transferred from ISAF to Afghan lead, with an ISAF presence maintained but the role of troops evolving from a “combat” to a “support” role.

The process started in July 2011. By the end of 2014, it is expected that Afghan authorities will have taken the lead throughout the country. At the 2012 Summit in Chicago, NATO leaders, together with the Afghans, will decide what additional support needs to be given to the ANSF to help them fulfil their fundamental tasks. In concrete terms, this will mean what further training and education are necessary to ensure that the Afghan forces and authorities have the skills and the support they need to keep their country secure.

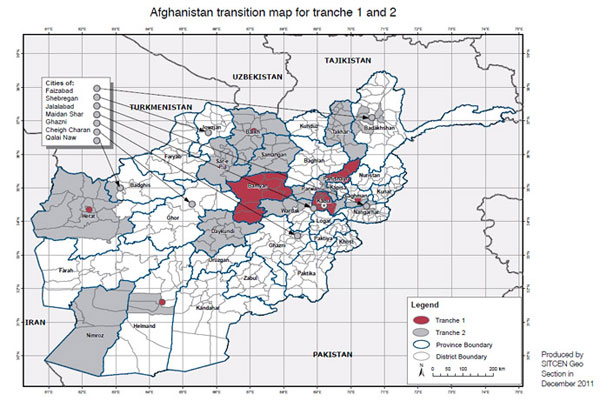

Afghan and NATO authorities have been assessing the readiness of areas for transition. On 21 March, the Afghan New Year, President Karzai announced the first Afghan districts to start transition; implementation of this first tranche began in July 2011. On 27 November, the President announced the second tranche of areas to initiate transition, with implementation begun in December 2011. As a result of these decisions, over 50 per cent of the population will live in areas under Afghan security lead. The transition process will continue until the end of 2014.

Afghan National Security Forces – NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan

NATO’s main effort in Afghanistan has increasingly focused on the training and development of the Afghan National Army (ANA) and the Afghan National Police (ANP), known collectively as the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). In January 2010 the Afghan Government, in discussion with the international community, agreed to grow the ANSF towards 305,600 personnel by October 2011. Increased training support to the ANSF, mainly through the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan (NTM-A), enabled Afghans to reach this ceiling, as planned. As a result, the insurgency is now facing an ANSF which has, since the beginning of 2010, grown by 110,000 soldiers and police. With this growth in both size and capability, Afghan army and police will continue to replace ISAF troops and assume an ever-increasing lead in providing security across the country.

The growth in size of the Afghan security forces has been matched by an improvement in the capabilities of Afghan forces. NTM-A has taken significant steps to improve and maintain quality: institutional training across Afghanistan now follows a standardized programme of instruction for the army and the police; ANSF leaders are entering the force with better training than their predecessors; there are now some 62 different training sites across Afghanistan and, at any one time, there are more than 34,000 Afghans in training at these sites. In order to protect this investment in professionalism, the quality of ANSF equipment has also been significantly improved and Afghan soldiers and policemen are now paid a living wage salary which meets or exceeds the national standard of living.

On average, there are 6,000 Afghan army recruits screened and placed into training each month, but only 14 per cent of them are literate. In order to address this, a mandatory literacy programme for the ANSF has been instituted. By November 2011, some 136,000 personnel had completed some combination of first, second or third grade literacy exams and another 90,000 were in training with the aim of the ANSF achieving over 60 per cent first grade literacy by the end of January 2012. The ANSF is well on track to reach and even exceed this target.

While significant progress has been achieved, challenges remain. For example, continued literacy training will be essential to enable further professionalization of the force, the retention rate needs to be improved to sustain the growth and cohesion of the force, and building effective leaders in sufficient numbers will be crucial in solving the most difficult challenges. In this regard, it is important for the broader international community, including ISAF contributing nations, to reconfirm their commitment to provide financial, material and training support for the ANSF and continue to help sustain the ANSF beyond 2014.

Afghanistan will one day stand on its own, but it will not be standing alone

With the conclusion of the transition process, the international community’s commitment to Afghanistan does not come to an end. As reinforced during the International Conference on Afghanistan held in Bonn in December 2011, the international community will remain strongly engaged in support of Afghanistan beyond 2014. And NATO will play its part. At the NATO Summit in Lisbon in November 2010, NATO and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan signed a Declaration on an Enduring Partnership. This partnership is the framework on which NATO will build its long-term engagement with Afghanistan, designed to continue after the ISAF mission. As NATO’s role shifts from a lead combat role to one of support, Allies and ISAF contributing countries have stressed they remain committed to Afghanistan. NATO will continue to stand by the Afghan people throughout transition and beyond.

Operation Unified Protector in Libya

Much of the world's attention in 2011 was focused on the crisis in Libya where NATO played a crucial role in helping protect civilians from attack or threat of attack. NATO's intervention to enforce a historic UN mandate was swift and was brought to a successful conclusion seven months after its start. This was one of the few occasions in which the UN Security Council has authorized the international community to intervene militarily to protect civilians from, in particular, their own government. The widespread and systematic acts of violence and intimidation committed by the Libyan security forces against pro-democracy protesters, as well as the gross and systematic violation of human rights brought the international community to agree on taking collective action.

In February 2011, a peaceful protest in Benghazi against the 42-year rule of Colonel Muammar Qadhafi was met with violent repression, claiming the lives of dozens of protestors in a few days. As demonstrations spread beyond Benghazi, the number of victims grew. The UN Security Council adopted Resolutions 1970 and 1973 in support of the Libyan people, "condemning the gross and systematic violation of human rights, including arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances, torture and systematic executions." The Resolutions introduced active measures including a no-fly zone, an arms embargo, and the authorization to member states, acting as appropriate through regional organizations, to use "all necessary measures" to protect Libyan civilians.

In support of broader international community efforts, the Alliance's decision to undertake military action was based on three clear principles: a sound legal basis; strong regional support; and a demonstrable need. The particular context of events in Libya in March 2011 met these criteria. With the adoption of UNSCR1973, several UN member states took immediate military action. NATO followed by enforcing the no-fly zone only six days later.

NATO took over sole command and control of all military operations for Libya on 31 March. It acted in full accordance with the UN mandate and consulted closely throughout with the UN, the EU, the League of Arab States and other international partners.

The NATO-led "Operation Unified Protector" had three distinct components:

- the enforcement of an arms embargo on the high seas of the Mediterranean to prevent the transfer of arms, related material and mercenaries to Libya;

- the enforcement of a no-fly zone in order to prevent any aircraft from bombing civilian targets; and

- air and naval strikes against those military forces involved in attacks or threats to attack Libyan civilians and civilian-populated areas.

At its peak, the NATO-led operation involved over 20 NATO ships in the Mediterranean, over 250 aircraft of all types, and was conducted in an area more than 1,000 kilometres wide. Of particular significance, it involved a coalition of NATO Allies and five non-NATO countries, including Sweden and mainly countries from the region (Jordan, Morocco, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates), thereby highlighting the strong regional support for NATO's operation.

NATO's strategy was defined by the mission, namely to take all necessary measures to prevent attacks and threats of attack against civilians and civilian areas. The most pressing and immediate task was to prevent attacks with tanks and heavy artillery on Benghazi. It also meant engaging with armed units that were attacking the city of Misrata. And it meant degrading ammunition supplies and command and control networks so that the regime's military commanders could not conduct or coordinate such attacks.

Overall, NATO conducted over 3,000 hailings at sea, almost 300 boardings for cargo inspection with 11 vessels being denied access to their next port of call. NATO flew over 26,000 sorties, of which 42 per cent were strike sorties damaging or destroying approximately 6,000 military targets. NATO assets flew an average of 120 sorties per day. In support of humanitarian assistance, NATO deconflicted nearly 4,000 air, sea and ground movements to allow missions by the UN, nongovernmental organizations and others to proceed unhindered.

There was an absolute requirement to minimize collateral damage and civilian casualties. Air strikes were therefore carried out with the greatest possible care and precision. Civilian infrastructure, such as water supplies and oil production facilities, was never targeted. At no time were there any forces under NATO command on the ground in Libya. The UN mandate was carried out to the letter, as stated by the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, in December 2011: “This military operation done by the NATO forces was strictly within (resolution) 1973."

The cumulative effect of NATO action to protect civilians was that the regime forces were gradually degraded to a point that they could no longer carry out their campaign country-wide.

The successful termination of the NATO-led operation and the fall of the Qadhafi regime have opened up a new chapter in Libya's history. For the first time in more than 40 years, the Libyan people have a unique opportunity to shape their own future. But the hard work of creating a new country and embarking on genuine reconciliation has only just begun. While there is no further operational role for NATO following the conclusion of Operation Unified Protector, NATO stands ready to assist the new Libyan authorities, upon request, in areas where it could provide added value. The new Libyan authorities have set up an interim government and elections will be held in 2012. In short, a period of transition has begun.

The NATO-led force in Kosovo

Throughout 2011, the NATO-led force in Kosovo – KFOR – has continued to provide peace and security in Kosovo. Under the mandate provided by UN Security Council Resolution 1244 of 10 June 1999, KFOR contributes towards a safe and secure environment in Kosovo and the freedom of movement for all people in Kosovo, irrespective of their ethnicity.

KFOR has continued to create the necessary conditions for other international actors and stakeholders to effectively perform their respective roles in Kosovo. In particular, the general improvement in the security situation in Kosovo greatly assisted in the deployment of the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo, with which NATO cooperates very closely on a daily basis. It has also allowed the Alliance to gradually adjust KFOR's military presence. Following a decision by NATO defence ministers, a reduction from 10,000 to 5,500 troops was successfully implemented by the end of March 2011.

The “unfixing process”

In parallel, KFOR has continued with the unfixing process of the original nine "Properties of Designated Special Status" in Kosovo. These sites have a particular religious, cultural and symbolic value and, over time, responsibility for their protection is handed over to the Kosovo police. Following the successful unfixing of five "Properties of Designated Special Status" to the Kosovo police in 2010, KFOR also implemented the handover of guarding responsibilities for the Archangel's site on 10 May 2011, and on 15 January 2012 for the unfixing of the seventh site, the Devič monastery.

The situation in Northern Kosovo

While KFOR has been successful in carrying out its UN mandate, the security situation abruptly deteriorated in Northern Kosovo in July 2011 over a customs dispute. Clashes ensued, resulting in two major spikes of violence in July and September, followed by a third in November, prompting the Alliance and its partners to adapt their posture on the ground. In this context, the NATO Operational Reserve Force was deployed in August, with a troop contribution of around 600 soldiers, in order to help bolster KFOR's deterrent presence in the North.

Amid the heightened tensions and clashes in Northern Kosovo, KFOR acted carefully, firmly and impartially, with a view to guaranteeing the population a stable environment, freedom of movement and security. Meanwhile, at the political level, NATO has continued to support the dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina under EU auspices, which is the only way out of the crisis. Both parties need to find a sustainable solution to a number of important issues as well as contribute to both the reconciliation and normalization process in the area.

These developments have prompted NATO to adjust its planned calendar. With the Operational Reserve Force deployed in order to strengthen NATO's deterrence posture, the reduction of KFOR has been delayed with the aim to ensure the ability to maintain a safe and secure environment if tensions arise. The Alliance will assess the situation at the beginning of 2012 and decide at what stage KFOR forces can be reduced to a lower level.

Counter-piracy

Piracy continues to be a serious security threat. Of the attacks reported in 2011, Somali pirates are responsible for over half of them according to the International Maritime Bureau (International Chamber of Commerce). Throughout 2011, NATO has remained actively engaged in combating piracy and armed robbery at sea off the Horn of Africa – and will continue to do so at least until the end of 2012 – in line with the relevant UN Security Council Resolutions and in close cooperation with other key organizations and countries involved.

Operation Ocean Shield

In 2011, NATO had on average 4-5 ships deployed in the area as part of Operation Ocean Shield, focused primarily on naval escorting and deterrence. It also provided three maritime patrol aircraft for a period of three months each time. This deployment of patrol aircraft – of which there is an overall shortfall – was of great value, especially in light of the limited availability of ships in the area and the expansion of pirates’ activities deep into the Indian Ocean.

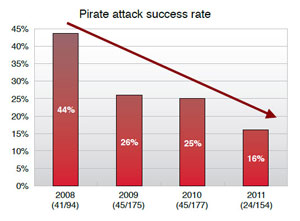

NATO ships have contributed to disrupting pirate action groups. Throughout 2011, there have been a total of 154 attacks in the Gulf of Aden, Somali Basin and the Arabian Sea. In the same period, naval forces disrupted 96 pirate vessels and only 24 vessels were pirated. The success rate of piracy incidents decreased in 2011 compared to 2010.3 This has been recognized by the UN Secretary-General in his 25 October 2011 report on piracy to the UN Security Council. However, the international community continues to be faced with increasingly well-armed, violent and bold Somali pirate gangs who are operating in a wider area.

There are, however, limitations to the effects of naval operations in rooting out piracy. It is important to help countries in the region build the capacity to fight piracy, and NATO is willing and able to assist in these efforts, within means and capabilities given the current economic climate. NATO is also aiming to develop its capacitybuilding activities, for instance working with the UN Support Office for the African Union Mission in Somalia and the International Maritime Organization.

Ultimately, there is a need to address the root causes onshore. NATO is making a contribution to this effort by supporting the African Union Mission in Somalia, at the African Union’s request, by providing subject matter expertise and participating in meetings of the International Contact Group on Somalia.

Training missions

NATO conducted a training mission in Iraq for several years. Although small-scale, the NATO Training Mission- Iraq (NTM-I) played an important role in training, mentoring and providing assistance to the Iraqi Security Forces in order to contribute to the development of Iraqi training structures and institutions. Since its launch in 2004, it trained over 5,200 commissioned and non-commissioned officers of the Iraqi Armed Forces and around 10,000 Iraqi police.4 These achievements have helped the Iraqi Government develop a baseline of enduring capability for their security forces and build a credible security sector.

The mission ended its work on 31 December 2011. However, NATO remains committed to developing a long-term relationship with Iraq through its structured cooperation framework and, in April 2011, the Alliance decided to grant Iraq partner status.

Tackling emerging security challenges

The security environment continues to change at a rapid rate and NATO has invested in 2011 to ensure that the Alliance is capable of meeting these emerging security challenges. Cyber attacks, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, terrorism and other emerging threats such as energy vulnerabilities increasingly affect the security of NATO's almost 900 million citizens.

Cyber defence

It is in the Alliance's interest to reduce national vulnerabilities, as well as anticipate crises and prepare for their management. Cyber attacks, for instance, can paralyze a country. They also have the potential to become a major component of conventional warfare. This realization has increased the urgency to strengthen cyber defences not only at NATO, but across the Alliance as a whole.

In 2011, NATO approved a new cyber defence policy and an action plan that will upgrade the protection of NATO's own networks and bring them under centralized management. The new policy also makes cyber defence an integral part of NATO's defence planning process, offering a coordinated approach with a focus on preventing cyber attacks and building resilience.

Since the cyber attacks against Estonia in 2007, NATO has been looking beyond the protection of its own communication systems to assist Allies seeking NATO support. The new policy, for instance, introduces the possibility for NATO's Rapid Reaction Teams to be dispatched, on the demand of individual member countries, for cyber incidents. Education and training capabilities will also be developed, principally through the Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn, Estonia, a NATO-accredited Centre of Excellence since 2008. The most recent Cyber Coalition 2011 exercise included six partners: Finland and Sweden were players, and Australia, Austria, Ireland and New Zealand sent observers, as did the European Union. The interest partners take in NATO's cyber security activities is constantly rising and is an integral part of the new policy.

Missile defence

Over 30 countries have or are acquiring missiles that could be used to carry conventional warheads and even weapons of mass destruction. The proliferation of these capabilities does not necessarily mean there is an immediate intent to attack NATO, but it does mean that the Alliance has a responsibility to protect its populations, territory and deployed forces. For several years, NATO has been pursuing a theatre missile defence programme for the protection of deployed NATO troops against ballistic missile threats with ranges of up to 3,000 kilometres. At the 2010 Lisbon Summit, NATO leaders decided to expand this programme to include the protection of NATO European territory, populations and forces.

A ballistic missile defence action plan was approved in June 2011 to outline how to achieve the NATO territorial ballistic missile defence. Efforts in the second half of 2011 were especially focused on implementing steps that will allow NATO to declare an interim NATO ballistic missile defence capability by the time of the Chicago Summit in May 2012. This objective is ambitious and will require further work to ensure that appropriate Allied command and control mechanisms are in place.

A key contribution to this capability comes from the United States through its sensors and interceptors deployed in Europe. To make the system truly comprehensive, other Allies also need to contribute similar assets, as they are already doing for the protection of deployed troops. These national elements will then be integrated into a single NATO network. It is the transatlantic element of NATO's missile defence system that makes it so significant both militarily and politically.

At the same time, NATO invited Russia to cooperate on ballistic missile defence. As Russia could also be threatened by ballistic missiles, it makes sense for NATO and Russia to cooperate in defending against them. NATO's vision is of two separate systems with the same goal, which could be made visible in practice by establishing two joint missile defence centres, one for sharing data and the other to support planning.

This cooperation is being developed in the spirit of the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, by which both parties agreed to refrain from the threat or use of force against each other. The work on the two objectives set in Lisbon to develop a Joint Analysis of a framework for future missile defence cooperation and to resume theatre missile defence cooperation, has been challenging, with differences impeding rapid progress. While trying to build trust, progress with Russia in this field has not been as substantial as hoped. Theatre missile defence work has focused on the development of a computer-assisted exercise. A related event is planned for March 2012, with a possible follow-up event later in the year. The development of the Joint Analysis is progressing, however, at a slow pace.

Terrorism

In 2011, NATO remained engaged in developing measures to defend against terrorism. The Alliance supported science and technology work in the fields of explosives detection, in particular, with a unique project involving Russia and NATO. The project, known as Standex, aims to counter the threat of attacks by improvised explosive devices on individuals circulating in large public areas such as airports or metro stations. It integrates a combination of different techniques and technologies for the detection of explosives and the localization, recognition, identification and tracking of potential perpetrators of attacks. In 2011, NATO also focused on the protection of critical infrastructure, including harbour security and route clearance. Moreover, the Allies made significant progress in developing a system with Russia that will help prevent terrorist attacks which use civilian aircraft - such as the 9/11 attacks against the United States. This new airspace security system will function by sharing information on airspace movements and by coordinating interceptions of renegade aircraft. Its operational readiness was declared in December 2011.

Modernizing NATO

At a time of financial crisis, governments are faced with difficult budgetary choices. For most Allies, this has meant rapidly seeking solutions to bring budgets back into balance, with an inevitable impact on defence spending.

At the Lisbon Summit in November 2010, the Allies reacted collectively to the effects of this crisis and launched a NATO-wide reform process not only reflecting austerity measures taken in member countries, but seeking to make the Alliance more modern, efficient and effective. Each and every one of NATO's political and military structures is being streamlined. The acquisition of critical capabilities is being reassessed to ensure that the Allies can acquire capabilities and ensure greater security with more value for money.

Modernizing structures

Reform of the military command structure

The NATO Command Structure is the backbone of the Alliance. It enables the implementation of political decisions by military means, providing for the command and control of NATO's military operations, missions and activities. As such, it underpins the credibility of the North Atlantic Treaty.

The Command Structure has been thoroughly reviewed with the objective of making it more effective, leaner and affordable. In June 2011, defence ministers agreed a revised structure that will reduce manning by one third, from over 13,000 to 8,800. In addition to these reductions, there is also a new emphasis on deployability. Both of the joint force headquarters in Brunssum and Naples ("joint" implying the participation of all three forces: land, air and naval) and air operations centres (in Germany, Italy and Spain) can deploy as need be to respectively exercise command and control over, as well as support, operations in theatre.

The new structure also places increased reliance on national command and control capabilities and the NATO Force Structure, which comprises the organizational arrangements that bring together national forces placed at the disposal of the Alliance. This is necessary for the Alliance to meet its level of ambition, which is defined as NATO being able to provide command and control for two major joint operations (such as the NATO-led operation in Afghanistan) and six smaller military operations (such as Operation Active Endeavour in the Mediterranean) at any one time.

Beyond the Alliance's three essential core tasks – collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security – which were highlighted in the 2010 Strategic Concept, the reform of the Command Structure also takes into account a number of new tasks and requirements such as missile defence and civil-military planning. The new NATO Command Structure should reach Initial Operational Capability by the end of 2013 and be fully implemented by end 2015.

NATO Agencies reform

NATO Agencies employ 6,000 people working in seven countries with a total business volume of over 10 billion Euro in 2010. They are essential to NATO, providing critical support to current operations, including Afghanistan, and managing the procurement of major capabilities such as the Eurofighter.

NATO Agencies are being consolidated and rationalized to enhance efficiency and effectiveness in the delivery of capabilities and services, to achieve greater synergy between similar functions and to increase transparency and accountability. A detailed implementation plan was approved in June 2011 and significant steps have been taken to transfer functions and services of a majority of the 14 agencies into three new agencies, which will focus on communications and information; support; and procurement. These are expected to be set up by the North Atlantic Council in June 2012.

As the reform moves forward, the specific needs of multinational programmes are being guaranteed throughout the process, and capability and service delivery are being preserved, especially where operations are concerned. Savings resulting from the reform should be in the region of 20 per cent of the running and personnel costs. In view of the level of estimated transition costs, additional savings will become more apparent in the longer term, as is the case with all such reforms.

Integration of structures involved in crisis management

Alliance crisis-management procedures were rationalized during 2010 and proved effective in the Libya crisis. In particular, since Lisbon, new working methods have been introduced for a more effective, integrated approach, which reflects NATO's commitment to a truly comprehensive approach to crisis management.

Two complementary elements of a civilian crisis-management capability have been formed within NATO structures. A Civil-Military Planning and Support Section was set up within the International Staff at NATO Headquarters. It supports analysis, planning and conduct of operations; it injects the civilian dimension in the planning phase, ensuring that the views and concerns of other actors and organizations are considered and that the necessary operational interaction is achieved throughout the entire crisis spectrum. Additionally, NATO civil and military bodies are also moving forward in their adaptation of relevant planning procedures. In support of these efforts, work continues to refine the non-military expertise available to NATO and to enable its effective use.

Headquarters reform

Against a backdrop of changing priorities and real budgetary pressures, efforts are underway to modernize and streamline working practices at NATO Headquarters. Major steps have been taken to reduce the committee structure and to enhance the sharing of information. The International Staff and the International Military Staff working at NATO Headquarters are being collocated according to their area of responsibility, helping to ensure a coherent and joint approach to policy development and implementation. As part of these changes, the International Staff are evolving towards a leaner, more flexible workforce sharply focused on NATO's priority areas. All of these changes are designed to ensure that with the inauguration of the new headquarters in 2016, a new NATO will move into a new headquarters.

Modernising capabilities

The crisis in Libya clearly demonstrated the importance of maintaining modern capabilities in an unpredictable security environment. However, in the current economic climate, defence budgets are being severely cut and the spending gap between the United States and other Allies is deepening. To counter this trend, NATO continues to "spend better" through what has been coined "smart defence". NATO continues to prioritize the Alliance's most pressing capability needs, set targets for forces and to assess how and where Allies use their resources to help them ensure maximum value for money.

Impact of the economic crisis on defence spending and capabilities

The effects of the current economic crisis on defence spending have been considerable. In 2011, the annual defence expenditures of 18 out of 28 Allies were lower than they had been in 2008. Further reductions have been announced or can be anticipated and this at a time when the defence spending and military capabilities of a number of countries outside the NATO area are increasing.

Allies continue to pursue the transformation of their forces to be able to meet future risks more efficiently by modernizing and restructuring their forces, and making them more deployable, sustainable and interoperable. Allies agree that this requires adequate defence spending, including on the modernization of equipment. However, cuts in defence spending have entailed significant delays or cancellation of major equipment projects in many countries, thereby putting into question equipment recapitalization and transformation efforts at a time when existing equipment is ageing and is subject to increased wear as a result of its use during current military operations. There have also been widespread reductions in training rates. A number of countries have also cut military and civilian personnel numbers and have reduced pay and allowances for personnel.

The Alliance does still retain sufficient forces and capabilities. However, this assessment is based on the over-reliance on a few member states, especially the United States, for the provision of costly and advanced capabilities. Concerns over the provision of adequate levels of some capabilities5 for recent operations have brought this imbalance into sharper focus. In the decade since 2001, the United States' share of total Alliance defence expenditures has grown from 63 to 77 per cent, resulting from both an 82.4 per cent increase in defence expenditures for the United States and a 5.7 per cent decrease in defence expenditures for NATO European nations, in real terms.

The defence spending6 of only three Allies is projected to be at or above 2 per cent of GDP in 2011 - the recommended level of defence spending agreed by Allies; 15 Allies are expected to spend less than 1.5 per cent of GDP on defence. Only eight Allies are expected to have spent 20 per cent or more of their defence expenditures on major equipment in 2011 - also the recommended level of spending agreed by Allies - while six will likely spend less than 10 per cent. The majority of Allies are facing difficulty in maintaining the proper balance between short-term operation and longer-term investment expenditures in light of decreasing defence budgets and increased expenditures rising from the cost of contributions to current operations.

"Smart defence"

To address these concerns, a new approach is needed. In 2011, NATO began to vigorously pursue a new way of acquiring and maintaining capabilities, captured by the term "smart defence". It is about member states building greater security - not with more resources, but with greater collaboration and coherence of effort. The way forward lies in prioritizing the capabilities needed the most, specializing in what Allies do best, and seeking multinational solutions to common problems. Priorities and shortfalls are well established through NATO's extensive and robust defence planning mechanisms. At the Lisbon Summit in 2010, Allies committed to focus their investment on 11 areas of the most critical needs, including missile defence, countering roadside bombs, medical support, command and control, and intelligence and surveillance. Specialization is sensitive because it touches on sovereignty, but in reality it is an essential management tool exercised by member states on a continuous basis. The key is for Allies to coordinate such

decisions transparently within the Alliance so that NATO retains collectively the capabilities needed to address the full range of missions.

Instead of pursuing purely national solutions, Allies have decided that where it is efficient and cost-effective, they will seek out more multinational solutions, including for acquisition, training and logistic support. By these means, Allies will improve the delivery of capabilities while fairly distributing the defence burden. To that end, defence ministers have agreed the need to deliver a range of substantive multinational projects by the 2012 Chicago Summit with a view to making the resulting capabilities available to NATO. This work is being closely coordinated with European Union staffs to avoid overlap with the EU initiative on pooling and sharing.

"Smart defence" should also provide a long-term vision for a new way of delivering capabilities. NATO is not starting from scratch. The Strategic Airlift Capability brings together 12 nations to procure and operate huge C-17 transport planes. By doing this together, they have acquired an important capability that individual members of the consortium could not obtain individually. And the ballistic missile defence programme allows national systems to operate jointly under NATO command and share early warning and data on the threat of incoming missiles.

Lisbon package of critical capabilities

Previous capability initiatives7 have helped generate new or additional capabilities for NATO but proved unable to rectify certain capability shortfalls. At the Lisbon Summit, NATO leaders agreed a new approach, centred on a package of the most pressing capability needs.8 These were carefully selected to help the Alliance meet the demands of ongoing operations, face emerging challenges and acquire key enabling capabilities. In general, implementation is proceeding satisfactorily, although not all of the financing aspects of the Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) programme have yet been agreed. This key transatlantic programme aims at procuring Global Hawk drones and associated systems, which with sophisticated radars, provide a broad and unfolding picture of what is happening on the ground. Operational experience has confirmed the importance of the package and particularly the need for an enduring NATO capability for joint intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

Usability

Alliance forces need to be adequately structured, prepared and equipped for crisis-response and out-of-area operations. Prior to the current economic downturn, shortfalls in the availability of forces for Allied purposes have already manifested themselves from time to time. A variety of measures have been used to tackle this problem such as, from 2004, a new focus on the so-called usability of Alliance forces. Under this initiative, targets are set for the deployability and sustainability of Allies' land forces9, with a view to making more of them available for deployed operations, including out-of-area and at strategic distance. The deployability offorces is the number of forces Allies are able to send out that are prepared and equipped for an operation. The sustainability of forces is the overall land force strength that can be sustained on deployed operations for an extended period of time (this period being defined as a total of 18 months).

Between 2004 and 2010, the number of land forces that can be deployed and sustained has increased: the number of deployable troops has risen by just over 6.5 per cent and the number of sustainable troops by over 21 per cent. However, there are signs that this improvement is levelling off. While over half of NATO Allies now meet or exceed the target for the sustainability of land forces, NATO will continue to seek further improvements in the usability of Allies' forces.

To ensure that NATO and Allies get the best output (capabilities and forces) for the input (money and other resources) available, NATO is developing a set of indicators that will provide a more comprehensive picture of how and where Allies utilize their resources. These indicators will complement the reporting on the usability of Allies' forces. They are designed to help encourage further burden-sharing between Allies and reveal best practices that can be used for others to follow.

Cooperative security – multinational solutions to global issues

The 2010 Strategic Concept highlighted cooperative security as one of NATO's three core tasks. The logic of this is clear. Today's security challenges are increasingly transnational and the most effective responses include the broadest range of partners, countries and international organizations alike.

While reaffirming that the Alliance is committed to maintaining its "open door" policy for other European countries to become members, the Strategic Concept set the goal of enhancing partnerships through flexible formats that bring NATO and its partners together - across and beyond existing frameworks. Throughout 2011, NATO made substantial progress in implementing this goal.

The Libya operation demonstrated the Alliance's commitment to giving its operational partners a structural role in shaping decisions in NATO-led missions. From the day the Alliance began its UN-mandated operation to protect civilians in Libya, NATO's operational partners, including from the region, were around the table helping to shape and then endorse all political and operational decisions. The contribution of partners to all aspects of the mission was essential and will serve as a model for future operations.

The Strategic Concept underlined NATO's willingness to develop political dialogue and practical cooperation with any nations and relevant organizations across the globe that share NATO's interest in peaceful international relations. Looking beyond existing partnership structures and employing a flexible format that allowed for the inclusion of a broad group of countries who shared the same security concerns, a meeting was held on counter-piracy in September 2011. Representatives from 47 countries and organizations involved in counter-piracy in the Indian Ocean attended that meeting. More meetings with a wide range of nations and organizations on critical shared security concerns are expected to follow.

The development of NATO-Russia relations remained a priority in 2011. Following on from NATO's offer in Lisbon, intensive negotiations are underway to develop cooperation with Russia to defend Europe against the growing threat of missile attack. Even as those discussions continue, NATO has stepped up cooperation with Russia to fight the flow of drugs from Afghanistan and to help build the capacity of the Afghan Army. For the first time ever, a Russian submarine participated in a submarine rescue exercise in 2011, as well as Russian fighter jets in a live counter-terrorist exercise. While NATO and Russia still do not see eye to eye on all issues, the level and scope of NATO-Russia cooperation continues to grow in areas of shared concern.

Regarding relations with other international organizations, the assessment is mixed. The strategic partnership with the European Union has not yet fulfilled its potential, while the pace has accelerated with the United Nations due to the wide range of operational cooperation undertaken.

The Libya crisis also led to unprecedented contacts between the Alliance and the League of Arab States, whose support for the overall international efforts was essential. These relations should form the basis for a deeper engagement in the future. Indeed, NATO will seek a stronger relationship with the broader Middle East and North Africa region, principally by strengthening the Mediterranean Dialogue and Istanbul Cooperation Initiative. Allies will work closely with partners from the region to see how they can work better together to address common security challenges. Membership of the Mediterranean Dialogue will be open to Libya, if the country so desires, as a framework for political dialogue and focused practical cooperation.

Footnotes:

- World Bank figures

- Figures from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- Statistics provided by NATO’s Maritime Command HQ, Northwood, United Kingdom – the command leading NATO’s counter-piracy operation.

- Statistics provided by Allied Joint Force Command, Naples, Italy.

- For instance, combat search and rescue, suppression of enemy air defences, air-to-air refuelling, airborne early warning, signals intelligence and unmanned attack platforms are highly dependent on the United States, which provides approximately 75 per cent or more of these capabilities);

- Data in this paragraph is based on current prices and updated GDP as at November 2011.

- Defence Capabilities Initiative; Prague Capabilities Commitment.

- Current priority shortfalls for operations, including the Afghanistan Mission Network, with emphasis on capabilities that will endure beyond current needs, such as the Countering Improvised Explosive Devices (C-IED), strategic and tactical airlift, and collective logistics contracts, including for medical support; capabilities to deal with current, evolving and emerging threats - expansion of Active Layered Theatre Ballistic Missile Defence, protection against cyber attacks, and possible capability requirements associated with the needs of a Comprehensive Approach and Stabilisation and Reconstruction; and selected long-term critical enabling capabilities – Bi-SC (Strategic Command) Automated Information Systems (Bi-SC AIS), the Air Command and Control System (ACCS) and Joint Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR) including the Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) system.

- 40 per cent of land forces to be deployable and the ability to sustain 8 per cent on operations or other high-readiness standby; these targets were later raised to 50 per cent and 10 per cent respectively. In addition, they were supplemented in 2009 by targets for air forces (40 per cent deployable; 8 per cent sustainable).