Origins

My country and NATO

Poland and its NATO Allies in 1999

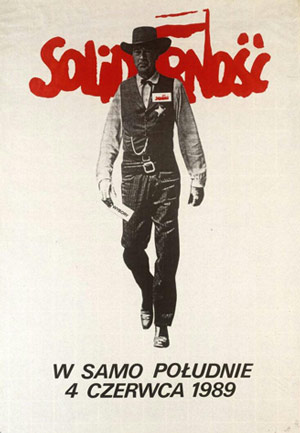

The emblem of “Solidarność” stands at NATO Headquarters in Brussels. It was unveiled in September 2020 to mark 40 years since the founding of the Solidarity movement.

NATO Secretary General Manfred Wörner (left) in Gdańsk with Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa (standing) during the Secretary General’s first official visit to Poland, 13 September 1990.

Visit by NATO Secretary General Manfred Wörner (at microphone, left) and Polish President Lech Wałęsa (at microphone, right) to the Polish Embassy in Brussels, Belgium, 3 April 1991.

First visit of Polish President Lech Wałęsa (left) to NATO Headquarters in Brussels, 3 July 1991.

NATO Secretary General Manfred Wörner (centre) and his wife Elfie Wörner (left) are greeted by Polish Foreign Minister Krzysztof Skubiszewski as they disembark the plane during a visit to Poland, 11 March 1992.

Polish Prime Minister Hanna Suchocka – the first woman to serve in the role – shakes the hand of NATO Secretary General Manfred Wörner during her visit to NATO Headquarters in Brussels, 7 October 1992.

A Polish soldier pops his head out of a tank during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94 – the first NATO PfP exercise, held in the Biedrusko training area near Poznań, Poland on 12-16 September 1994.

A Ukrainian soldier looks through the sight of a shoulder-mounted rocket launcher during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

Troops scrambling from Polish helicopter PZL Swidnik W - 3 Sokół during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

A Czech soldier uses a wire bridge to cross a river during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

A soldier loads ammunition into a rifle during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

Weapons familiarisation between US and Lithuanian troops during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

Soldiers standing in formation during the opening ceremony of Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

Soldiers practise their accuracy at a firing range during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

Soldiers walk across a grassy field during Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

A Polish soldier and a US soldier chat on the side lines of Exercise Cooperative Bridge 94.

Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski (centre) shakes hands with Czech President Václav Havel (left) and Hungarian Prime Minister Gyula Horn (right) at the 1997 Madrid Summit.

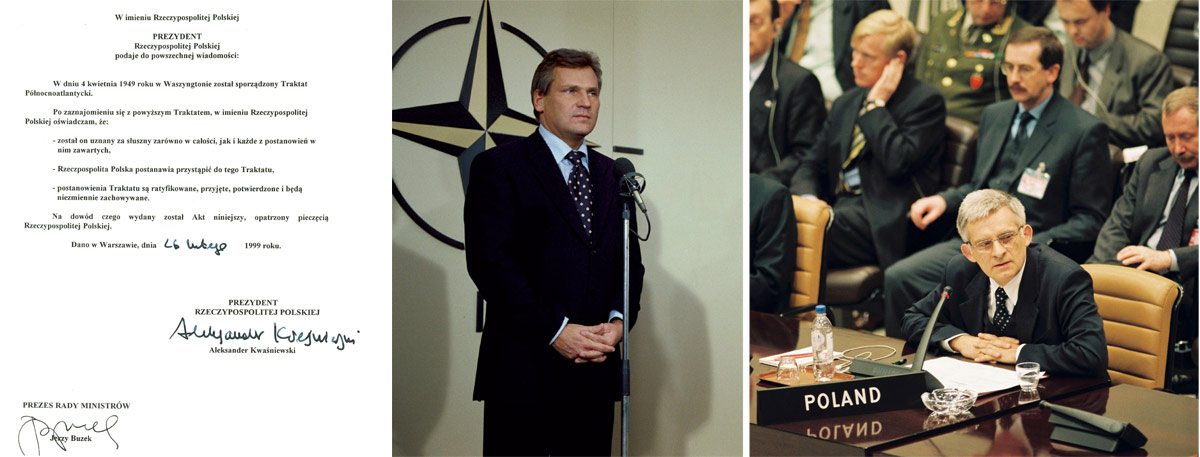

Poland’s Instrument of Accession to the North Atlantic Treaty (left) was signed by President Aleksander Kwaśniewski (centre) and Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek (right).

A military band performs at the flag-raising ceremony for Poland, Czechia and Hungary at NATO Headquarters in Brussels on 16 March 1999.

Polish Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek (left) watches his country’s flag rising at NATO Headquarters alongside (left-to-right) Czech Prime Minister Miloš Zeman, NATO Secretary General Javier Solana and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Two Polish officers salute with ceremonial swords after raising the Polish flag in front of NATO Headquarters in Brussels.

NATO Secretary General Javier Solana (centre) shakes the hand of Polish Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek after the Polish flag is raised at NATO Headquarters for the first time.

After the flag-raising ceremony, the North Atlantic Council – NATO’s principal political decision-making body – meets for the first time with 19 NATO Allies.

The North Atlantic Council applauds its new members – including Poland, represented by Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek.

Polish Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek takes his seat at the table for the first time as a NATO Ally.

Polish Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek celebrates Poland’s accession with a hug during the North Atlantic Council meeting.

Nineteen Allied flags fly in front of NATO Headquarters in Brussels for the first time.