Origins

My country and NATO

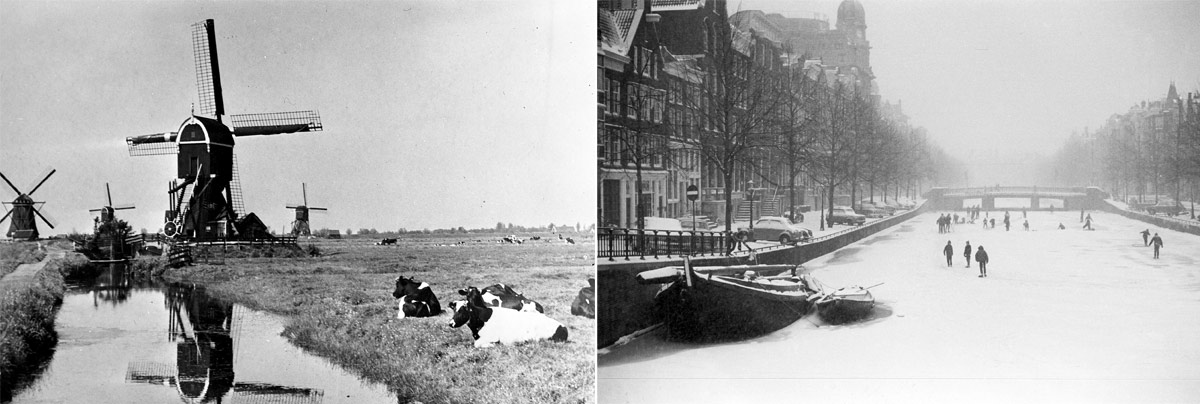

The Netherlands and its NATO Allies in 1949

Marshall Plan posters designed by Dutch designer and cartoonist F.J.E. Mettes (left) and entered for the Netherlands by artist Wladimir Flem (right)

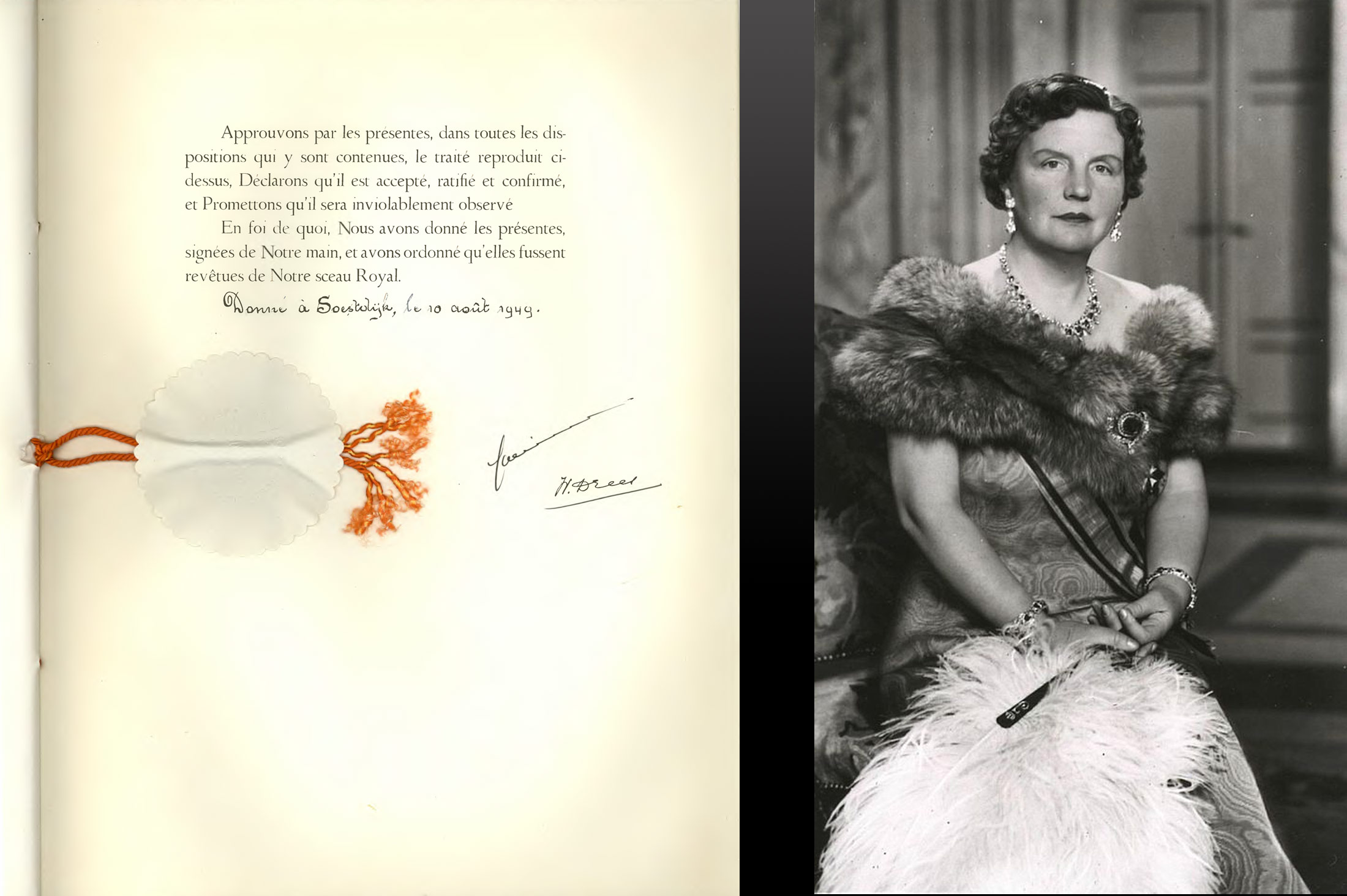

Her Majesty Queen Juliana of the Netherlands signs the Instrument of Accession in Soestdijk on 10 August 1949.

An exhibition on NATO in The Hague on the occasion of the Alliance’s 15th anniversary in 1964.

NATO exercise Full Play in Ypenburg, The Hague, 1958.

The Dutch Hawk missile battalion training in Germany in 1966.

Checking that everything is correctly installed. Dutch Hawk missile battalion training in Germany.

Dutch representatives at the NATO Conference of Senior Service Women Officers held at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, in the late 1960s.

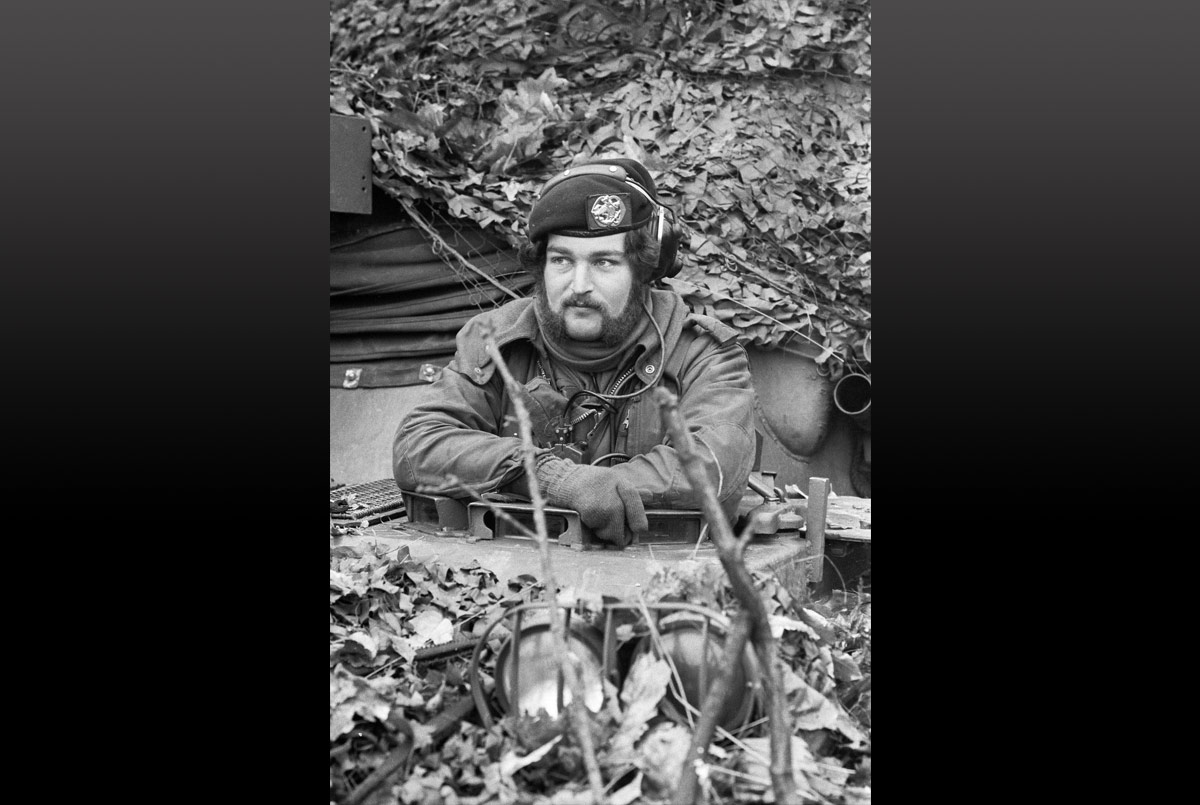

A Dutch soldier training during a NATO exercise, February 1977.

Journalists are invited to the exercise to interview participants and find out more on how exercises are conducted, February 1977.

A soldier explains to a journalist where the next manoeuvres will take place, February 1977.

Deciding on the best route to take, February 1977.

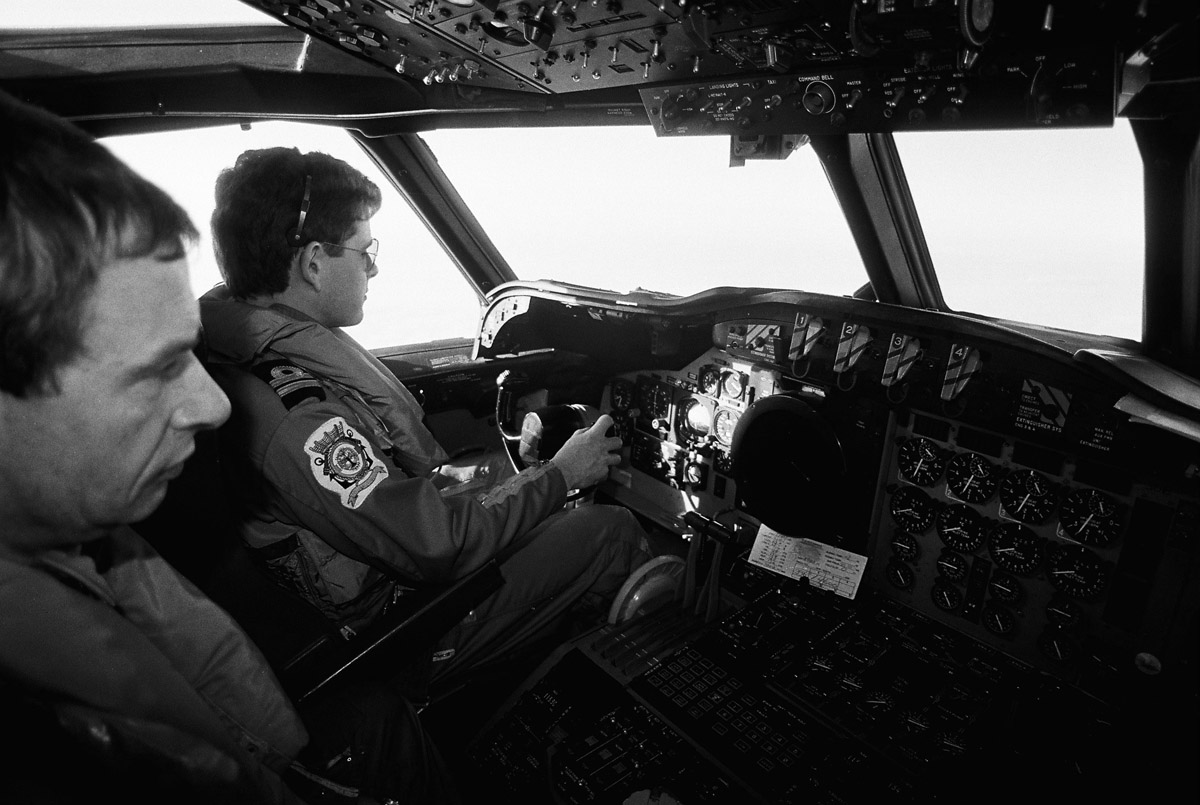

Dutch forces contribute to maritime surveillance in Iceland, February 1986, at the peak of Soviet activity in the North Atlantic.

A view from the cockpit.

HRMS Sittard moors during NATO Exercise Sharp Spear, September 1989. Source: Dutch MoD.

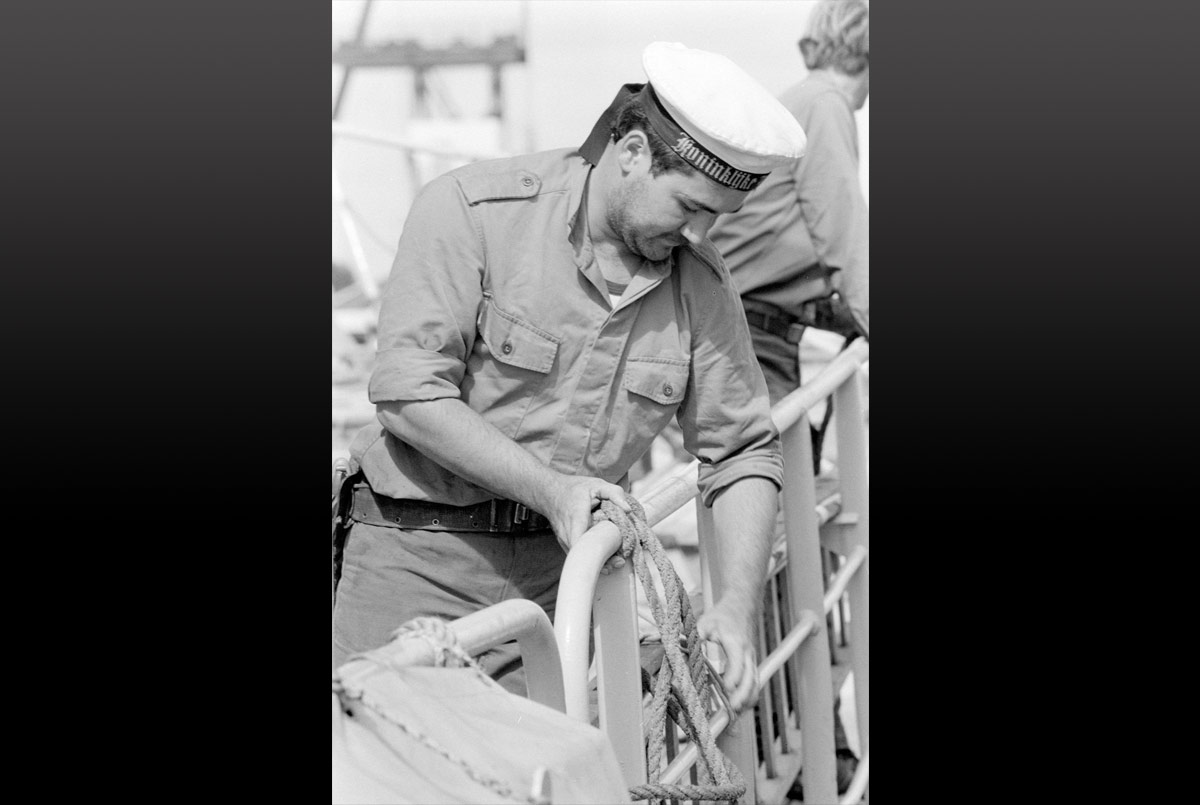

Ensuring the ropes are tightly knotted, Exercise Sharp Spear. Source: Dutch MoD.

HRMS Alkmaar during Exercise Sharp Spear. Source: Dutch MoD.

A team-sweep between NRMS Drachten and NRMS Naaldwijk during Exercise Sharp Spear, 1989. Source: Dutch MoD.

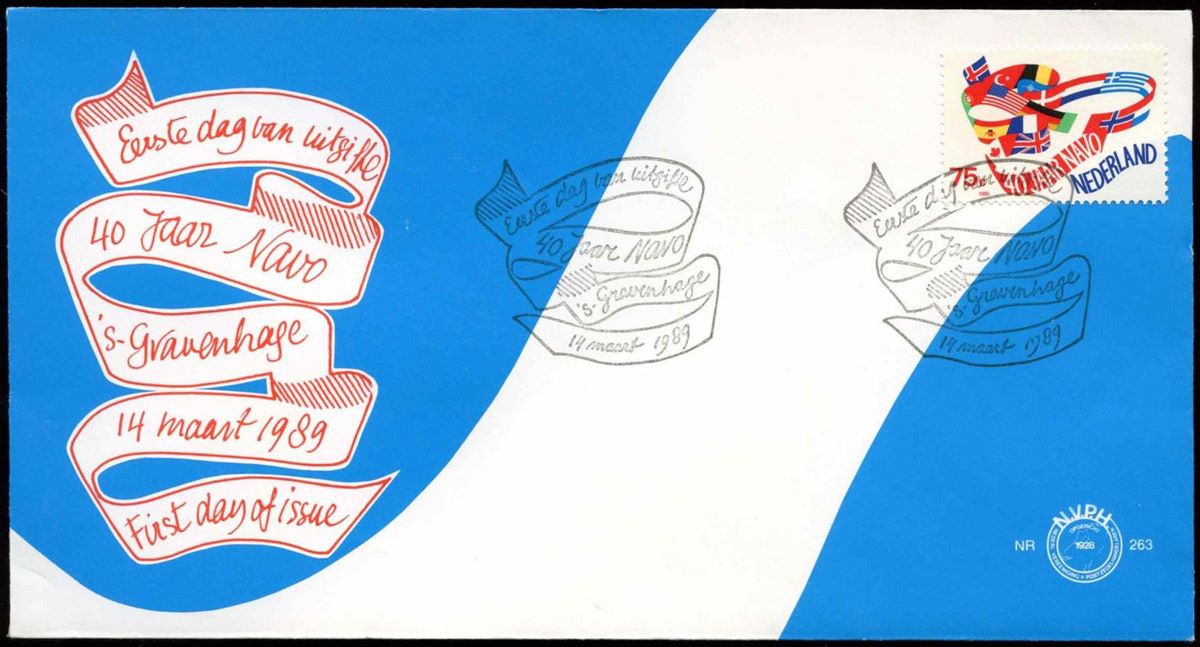

A first day issue stamp celebrating NATO’s 40th anniverary in 1989

The very tulips that adorn parks in Ottawa today were a gift from the Netherlands. They were offered by the Dutch after Canada had given refuge to Princess Juliana in 1943 during the birth of Princess Margriet. The Canadian government even declared the hospital room in which Princess Juliana lived territory of the Netherlands and a Dutch flag was allowed to fly from the Parliament building – the only flag of a foreign country ever to have been allowed to fly on the Peace Tower.

The very tulips that adorn parks in Ottawa today were a gift from the Netherlands. They were offered by the Dutch after Canada had given refuge to Princess Juliana in 1943 during the birth of Princess Margriet. The Canadian government even declared the hospital room in which Princess Juliana lived territory of the Netherlands and a Dutch flag was allowed to fly from the Parliament building – the only flag of a foreign country ever to have been allowed to fly on the Peace Tower.

The heiress to the throne, Princess Beatrix (left), and Princess Irene (right) are hosted by NATO Secretary General Dirk Stikker at NATO Headquarters in Paris, France, in September 1963.

The heiress to the throne, Princess Beatrix (left), and Princess Irene (right) are hosted by NATO Secretary General Dirk Stikker at NATO Headquarters in Paris, France, in September 1963. Joseph Luns arrives at NATO Headquarters for his first day at work.

Joseph Luns arrives at NATO Headquarters for his first day at work.