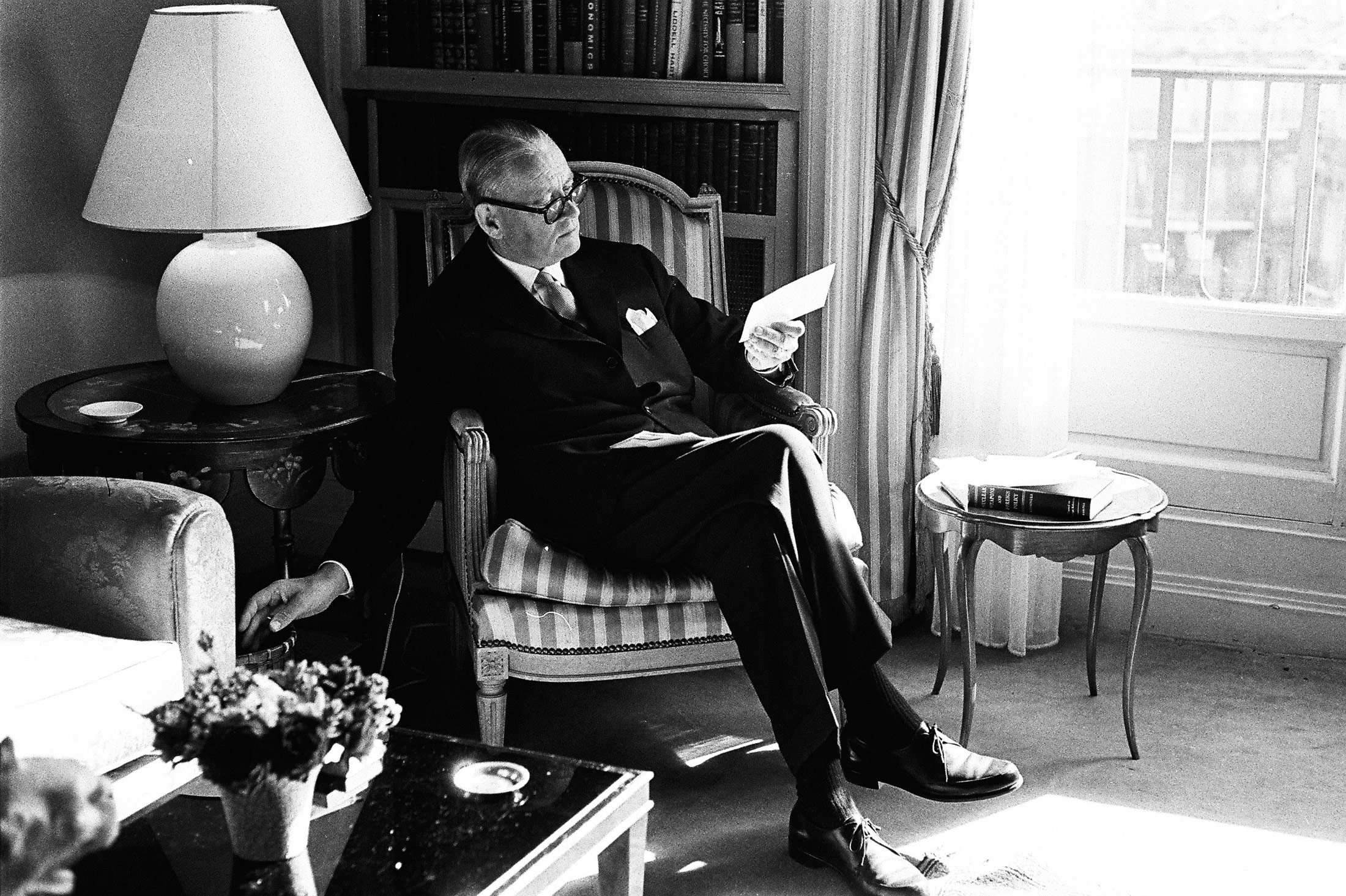

Dirk Uipko Stikker became the third Secretary General on 21 April 1961. His name in connection with NATO was already a familiar one. As Foreign Minister of the Netherlands, Stikker signed the North Atlantic Treaty in 1949. And from July 1958 to April 1961, he was the Permanent Representative of the Netherlands to NATO.

Stikker’s path to head of the Alliance was not without its twists and turns. His name was among those considered for the first Secretary General. It came up again in 1960 yet not without some internal debate. It was the height of the Cold War and nuclear policy was at the top of the agenda. France, under President General de Gaulle, had a tenuous relationship with NATO and the United States over this issue. A series of decisions eventually resulted in French withdrawal from the integrated command structure in 1966. The ongoing tension spilled over into the appointment of a new Secretary General. Arguing that Stikker was too sympathetic to the American view, France backed the Italian candidate Manlio Brosio. Stikker’s appointment was eventually approved and Brosio was chosen to succeed him in August 1964.

General de Gaulle refused to receive Stikker during his tenure but Stikker continued to make genuine efforts to maintain a working relationship with the French. At the same time, he remained unapologetically a staunch pro-Atlanticist. Stikker frequently visited the United States and got along very well with President Kennedy.