Origins

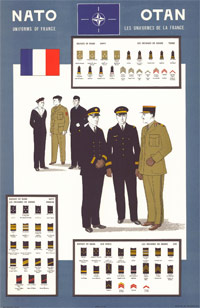

My country and NATO

France and its NATO Allies in 1949

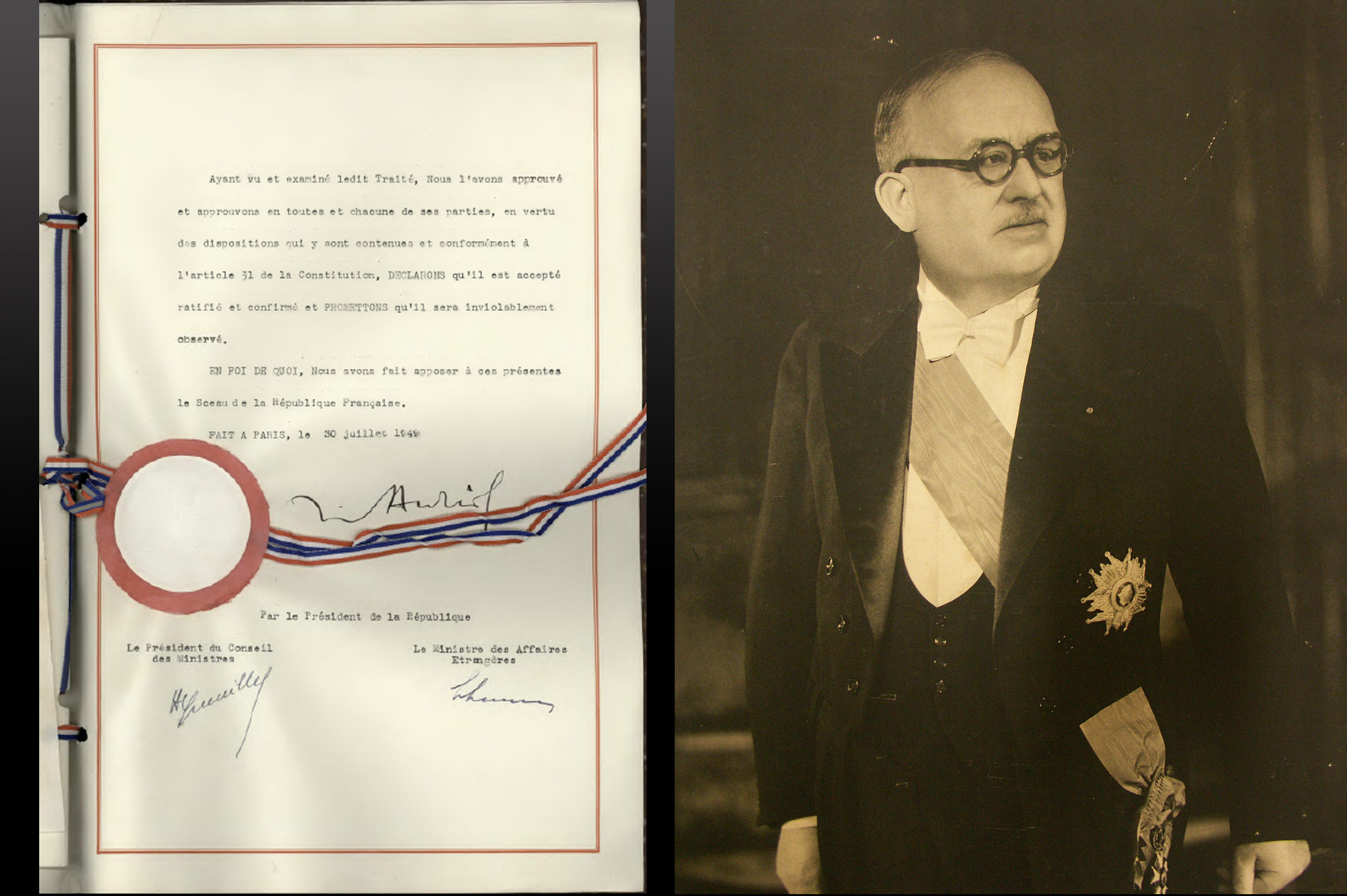

PARIS, 30 JULY 1949, THE PRESIDENT OF THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, VINCENT AURIOL, SIGNS THE INSTRUMENT OF ACCESSION FOR FRANCE

The monumental, neoclassical Palais de Chaillot was built for the Paris Worlds Fair in 1937 by architects Léon Azéma, Jacques Carlu and Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, who competed in the Grand Prix de Rome.

In 1948, prefabricated buildings were erected to host the United Nations General Assembly at which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was signed.

NATO was housed in the UN buildings starting in 1952. It was agreed that the Organization would occupy the offices for just six months; it nonetheless stayed there for eight years before moving into its new permanent headquarters at Porte Dauphine.

Two NATO officials riding a Vespa to work share a laugh with French policemen along the banks of the Seine.

Enjoying a break at the entrance to the Palais de Chaillot, which offers a breathtaking view of the Eiffel Tower and across the Champ de Mars.

Palais de Chaillot has an enviable location in the heart of Paris, allowing visitors to walk there.

For high-level meetings, ministers and heads of state arrive by limousine and emerge in the spotlight of NATOs press team and throngs of international journalists.

The cameras flash away...

Arrival of Paul-Henri Spaak, the Belgian Prime Minister of the time who would later become NATO's second Secretary General, in 1957.

On 23 October 1954, the Accession Protocol whereby West Germany joined NATO is signed at the Palais de Chaillot.

Rushing around and meeting up in the conference room concourse.

US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles takes one last look at the documents before heading into a meeting, with Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Luns looking on. Luns would become NATO's Secretary General in 1971.

The conference room concourse doubles as a working space.

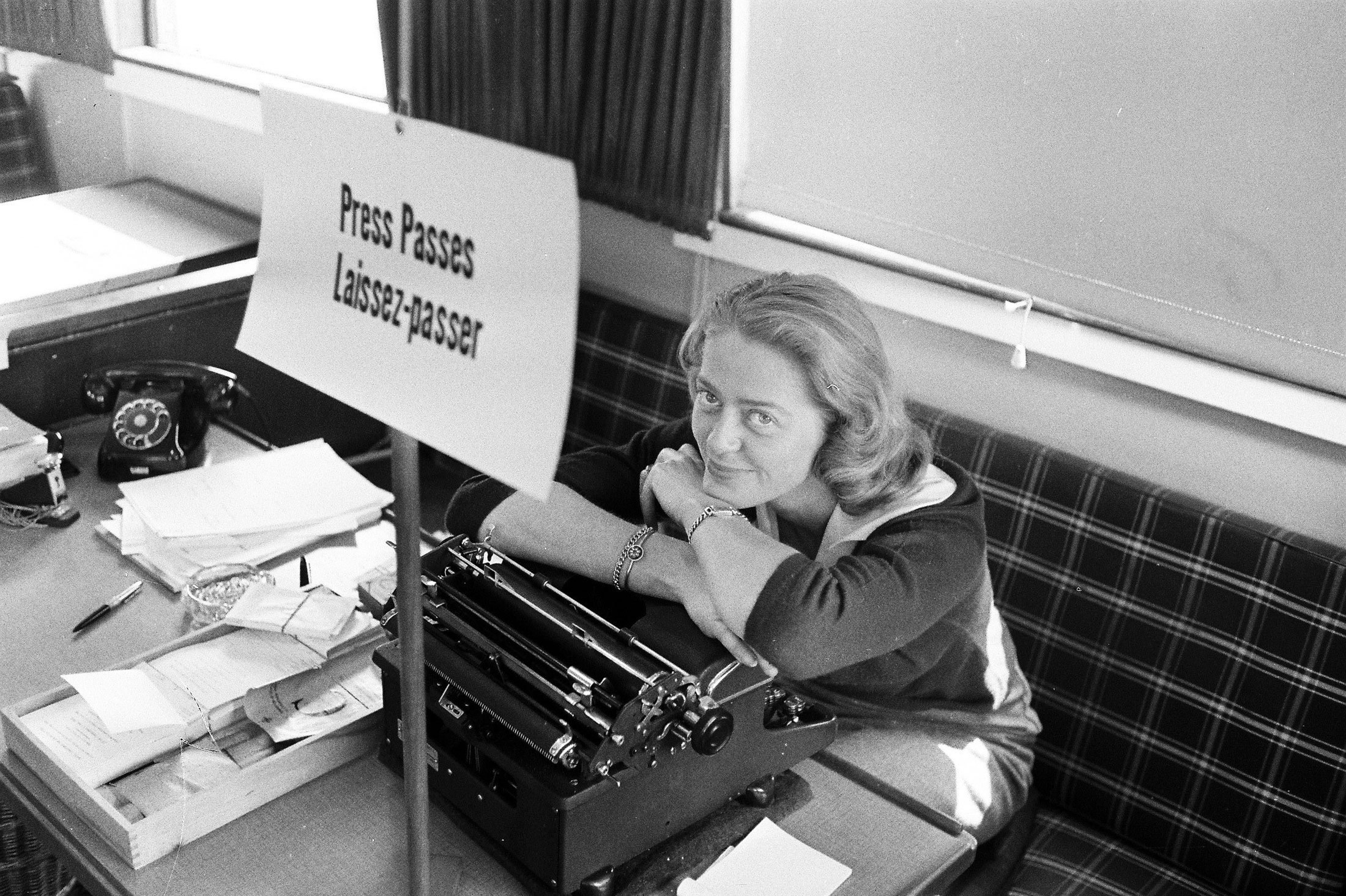

A member of the NATO press staff waits to issue journalists their accreditation.

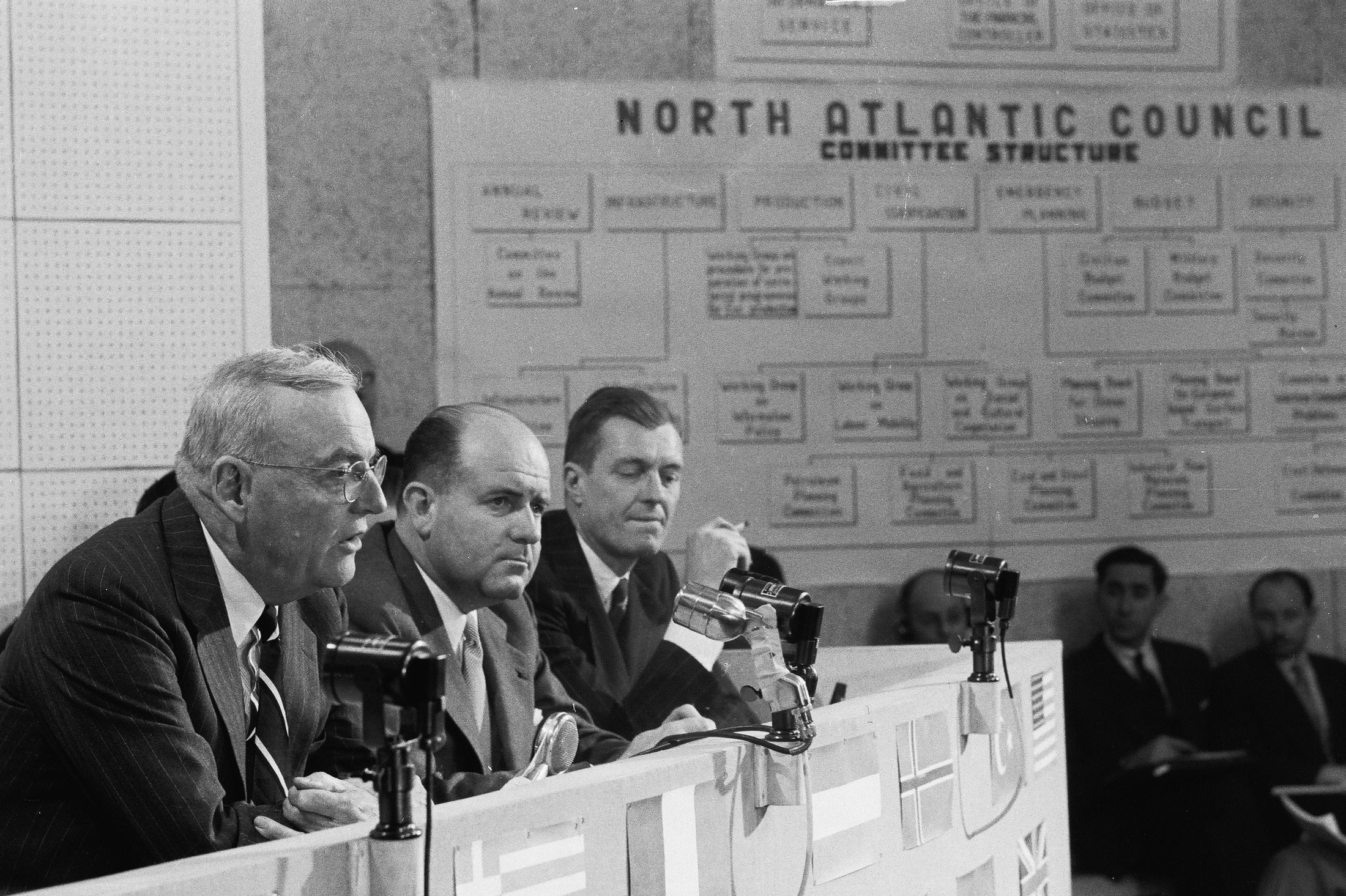

Press conferences are given

to an audience of attentive journalists.

Interpretation headsets are provided.

Switchboard operators are responsible for connecting international phone calls.

Journalists use telephone booths to call in their stories to their respective agencies in France.

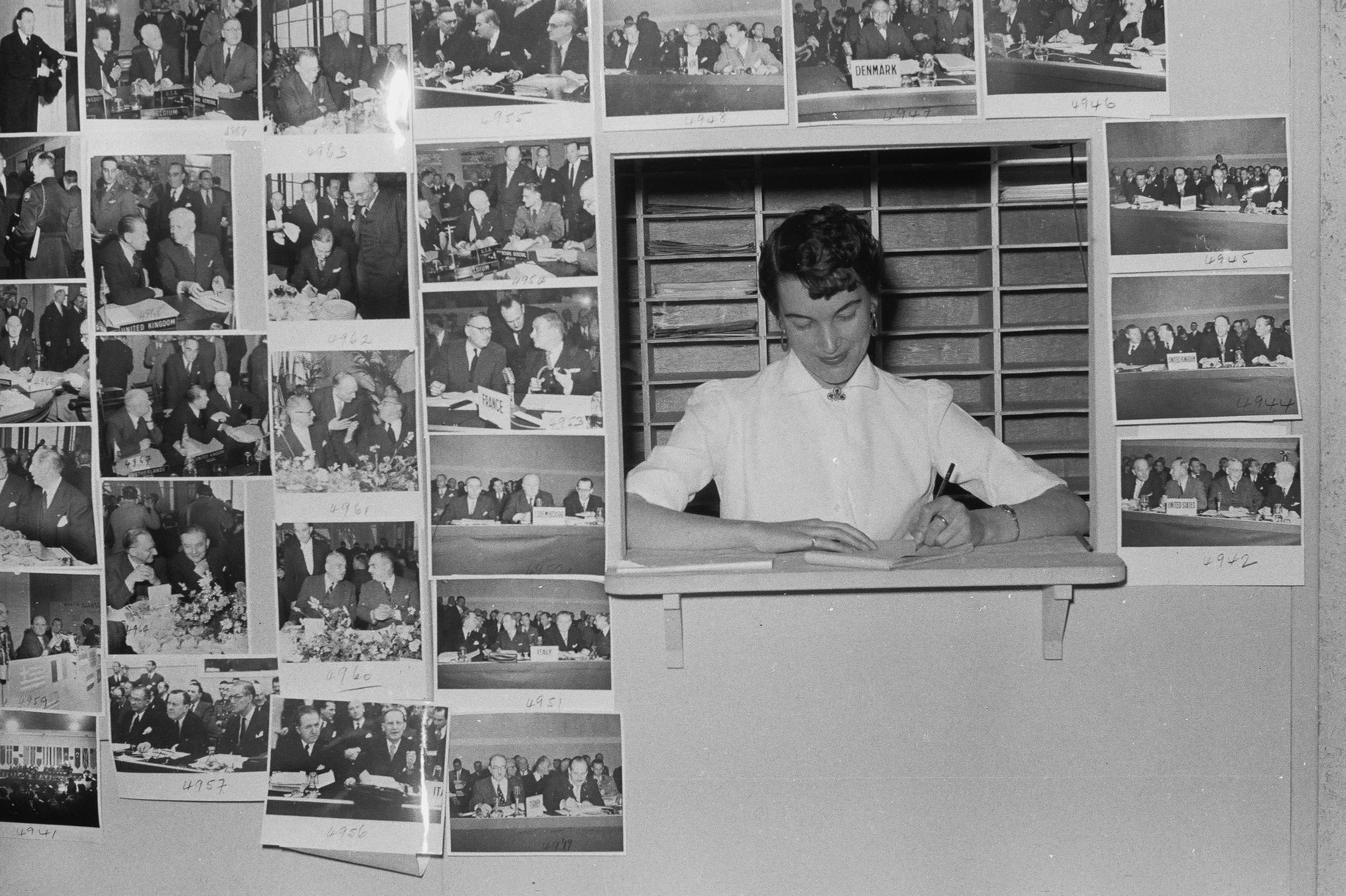

NATOs photographers busily working to select the best shots

which are then brought to the photo kiosk, where international journalists can pick them up to illustrate their articles.

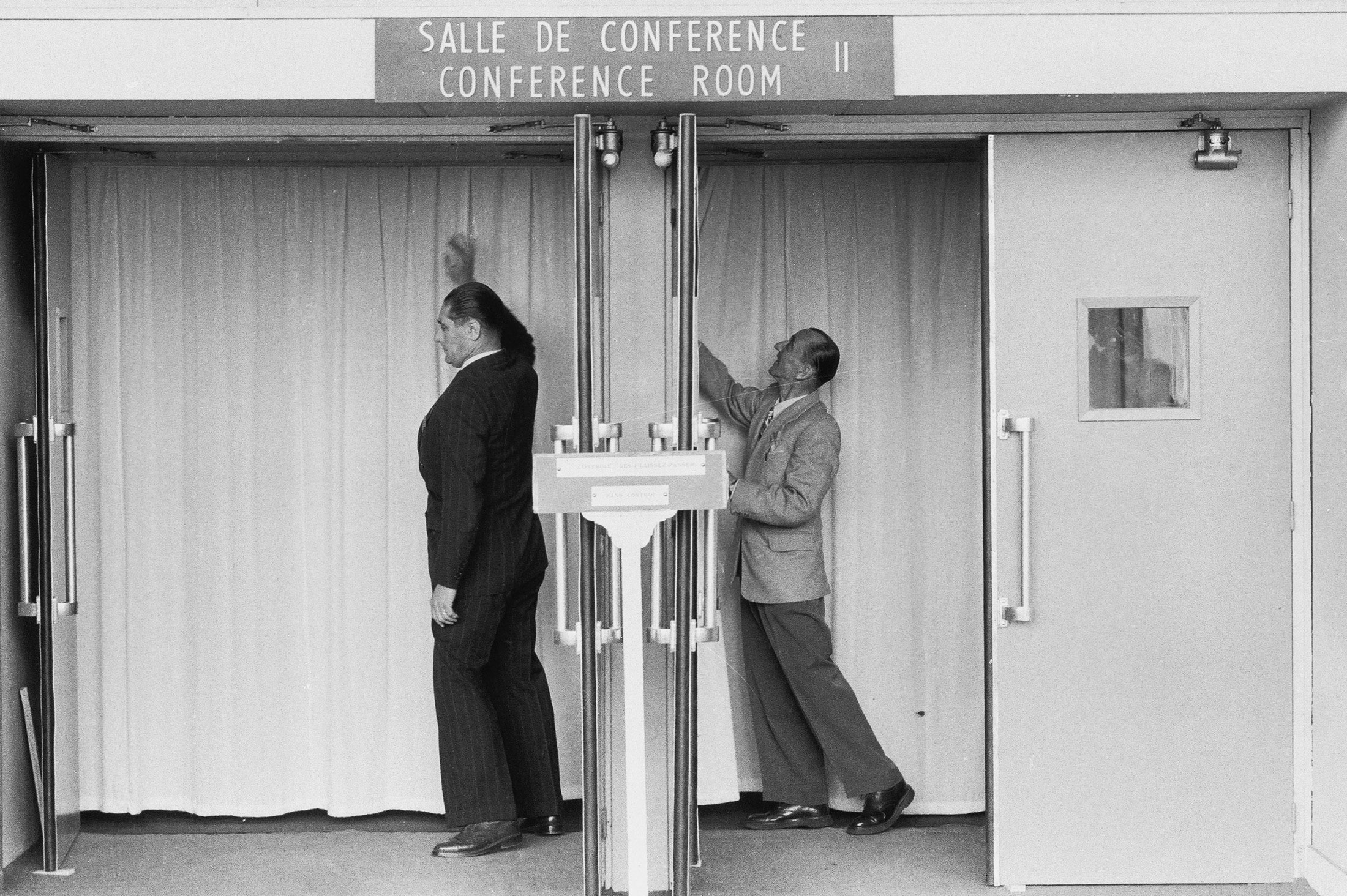

Anyone wishing to be allowed into ministerial meetings must show his or her pass.

Guards make sure that the meetings are not disrupted.

The Council Room

After summits and ministerial meetings, a family portrait is taken to capture the moment.

NATO officials' working day draws to a close.

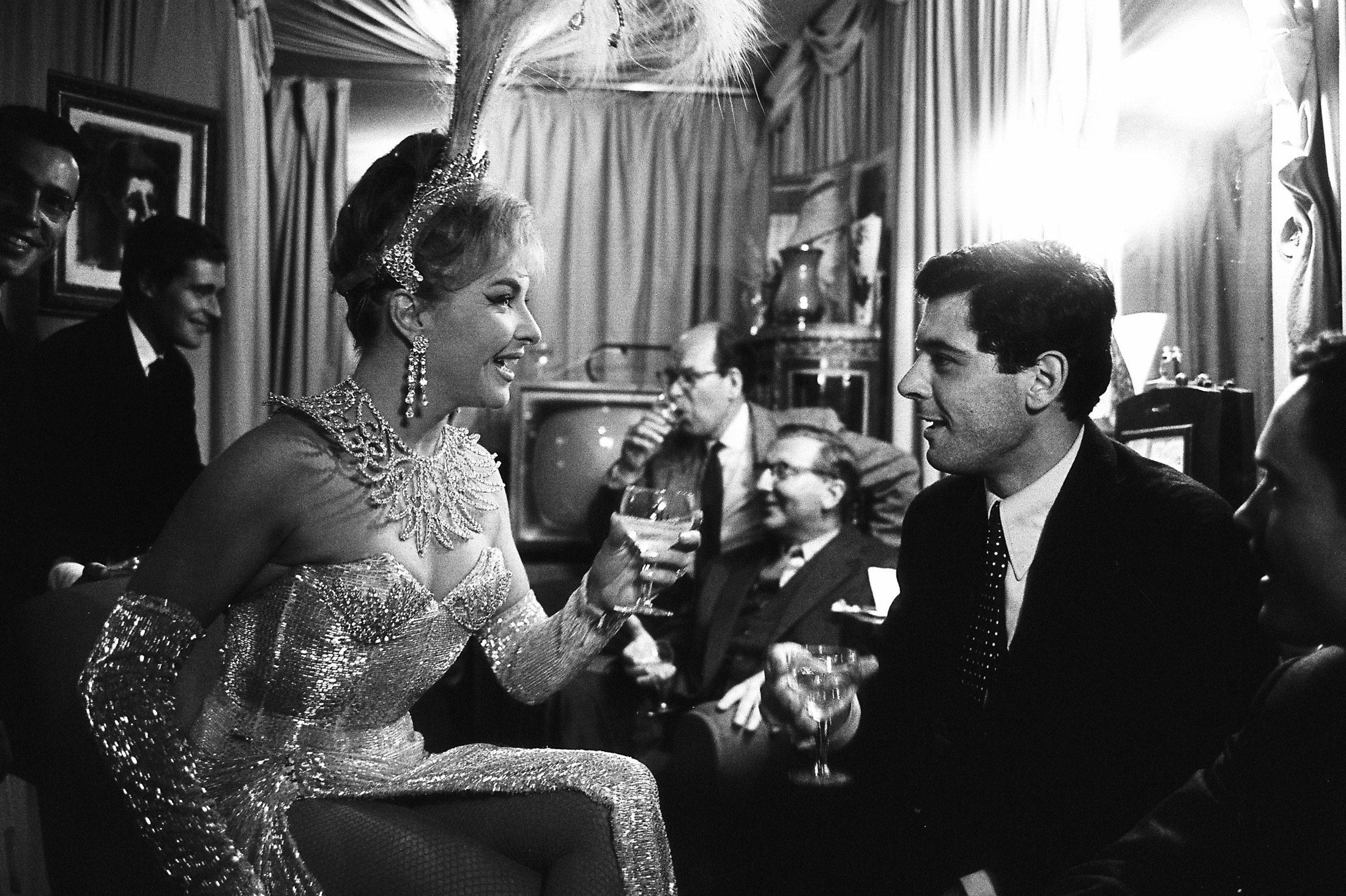

Some go to the Palais de Chaillot bar for a drink with colleagues.

Others opt for a leisurely stroll through the Jardins du Luxembourg.

SUMMER SCHOOLS AND EXHIBITIONS WERE USED TO INFORM THE PUBLIC

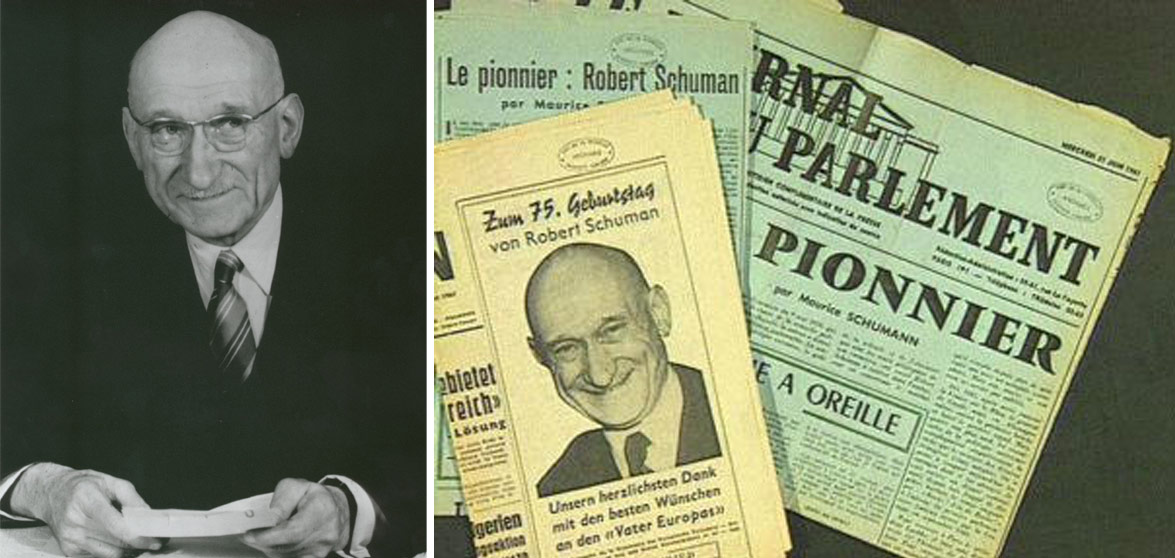

THE SCHUMAN DECLARATION OPENED THE WAY FOR A UNITED EUROPE

“A” FOR ALLIANCE

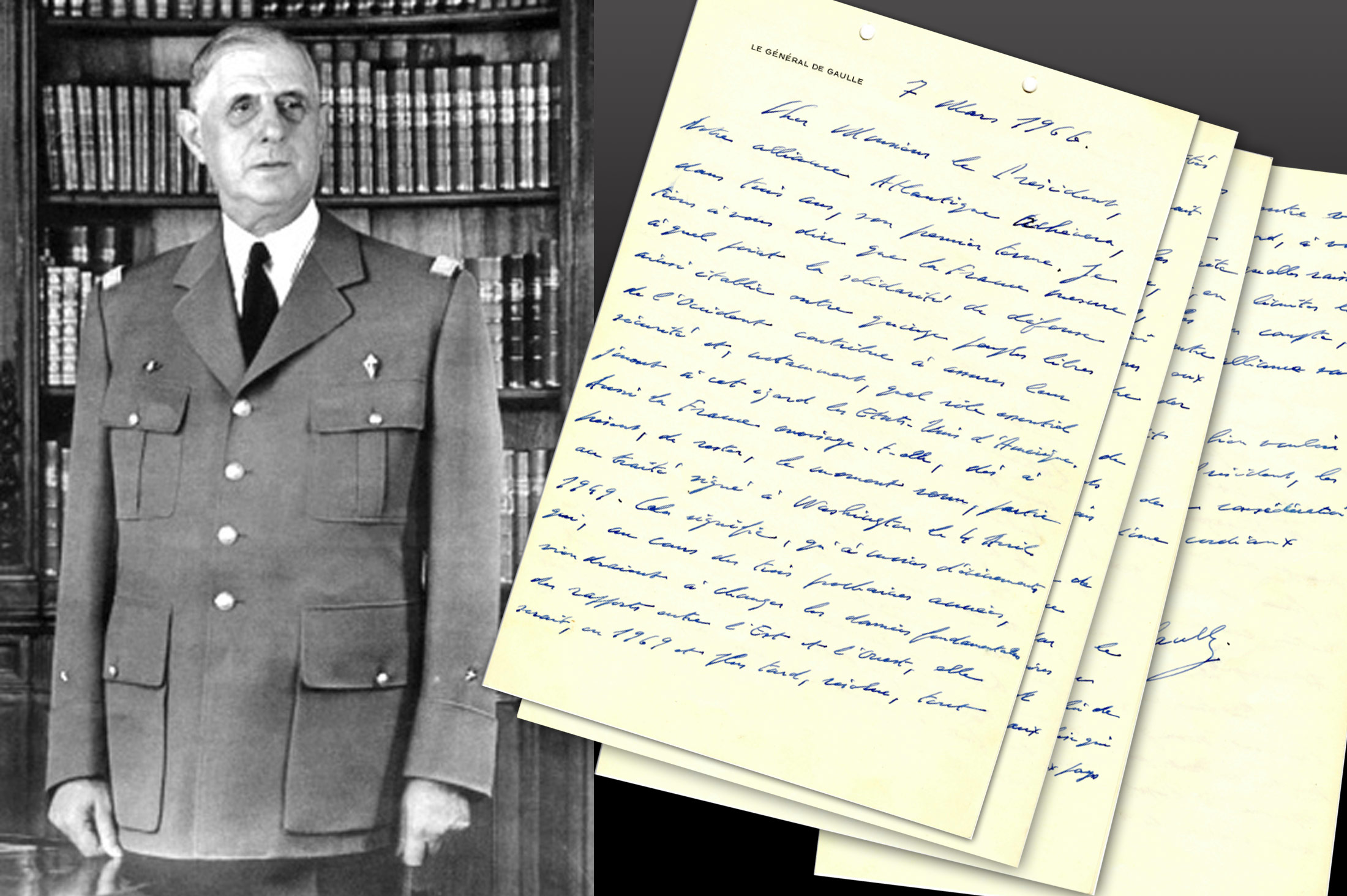

PRESIDENT DE GAULLE'S ORIGINAL HANDWRITTEN LETTER TO US PRESIDENT LYNDON B. JOHNSON

Before the 1988 Summit in Brussels, the security services of President François Mitterrand contacted the Organization to have an emergency exit installed in one of the meeting rooms where the President was scheduled to give a press conference. NATO's construction services had to scramble to complete the work, because the French President would only attend the Summit if this request was accepted. This door in the previous Brussels Headquarters was informally referred to by staff as the "Mitterrand door" (photo: President Mitterrand in the conference room in question).

Before the 1988 Summit in Brussels, the security services of President François Mitterrand contacted the Organization to have an emergency exit installed in one of the meeting rooms where the President was scheduled to give a press conference. NATO's construction services had to scramble to complete the work, because the French President would only attend the Summit if this request was accepted. This door in the previous Brussels Headquarters was informally referred to by staff as the "Mitterrand door" (photo: President Mitterrand in the conference room in question).