Humble beginnings

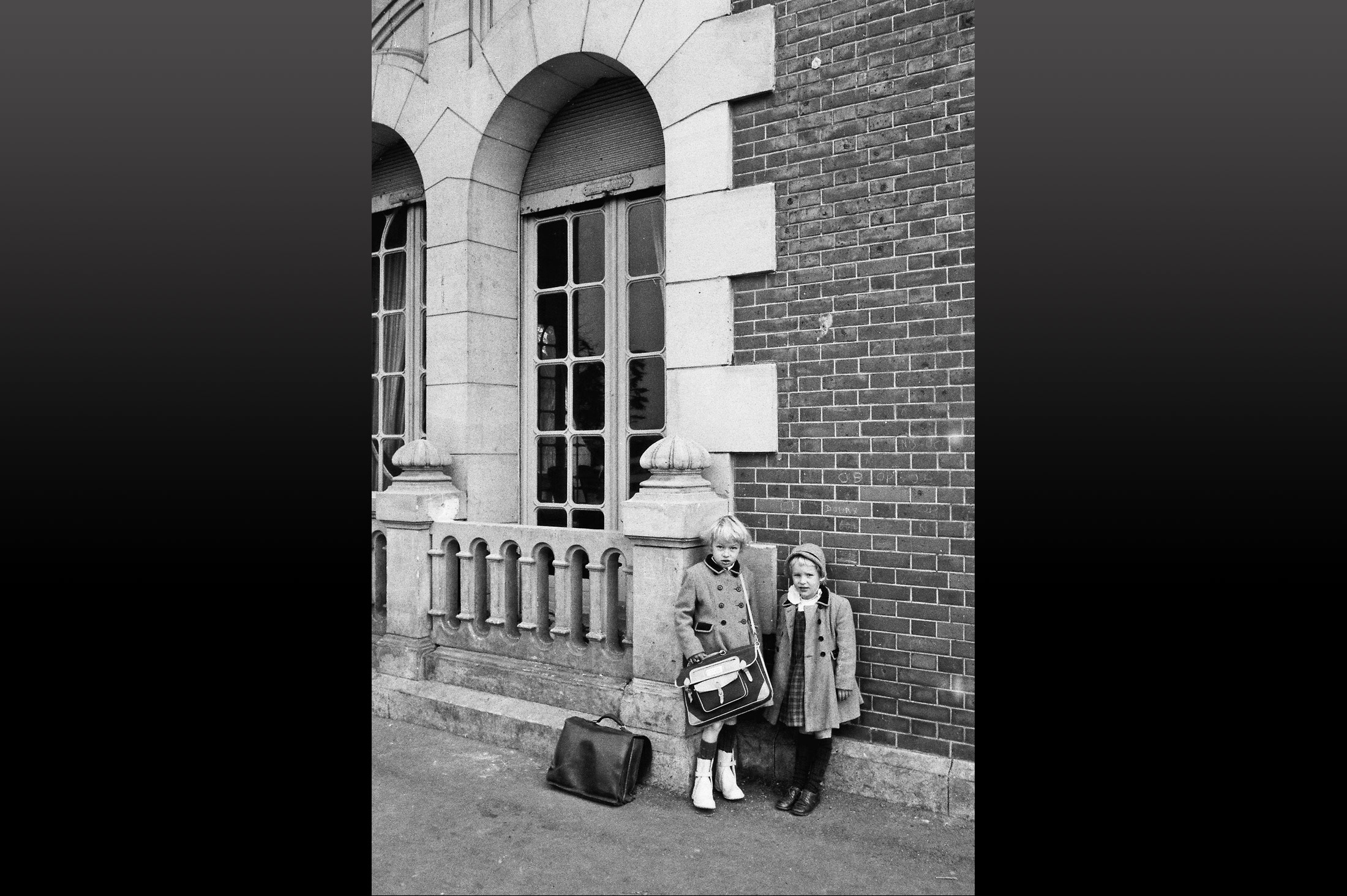

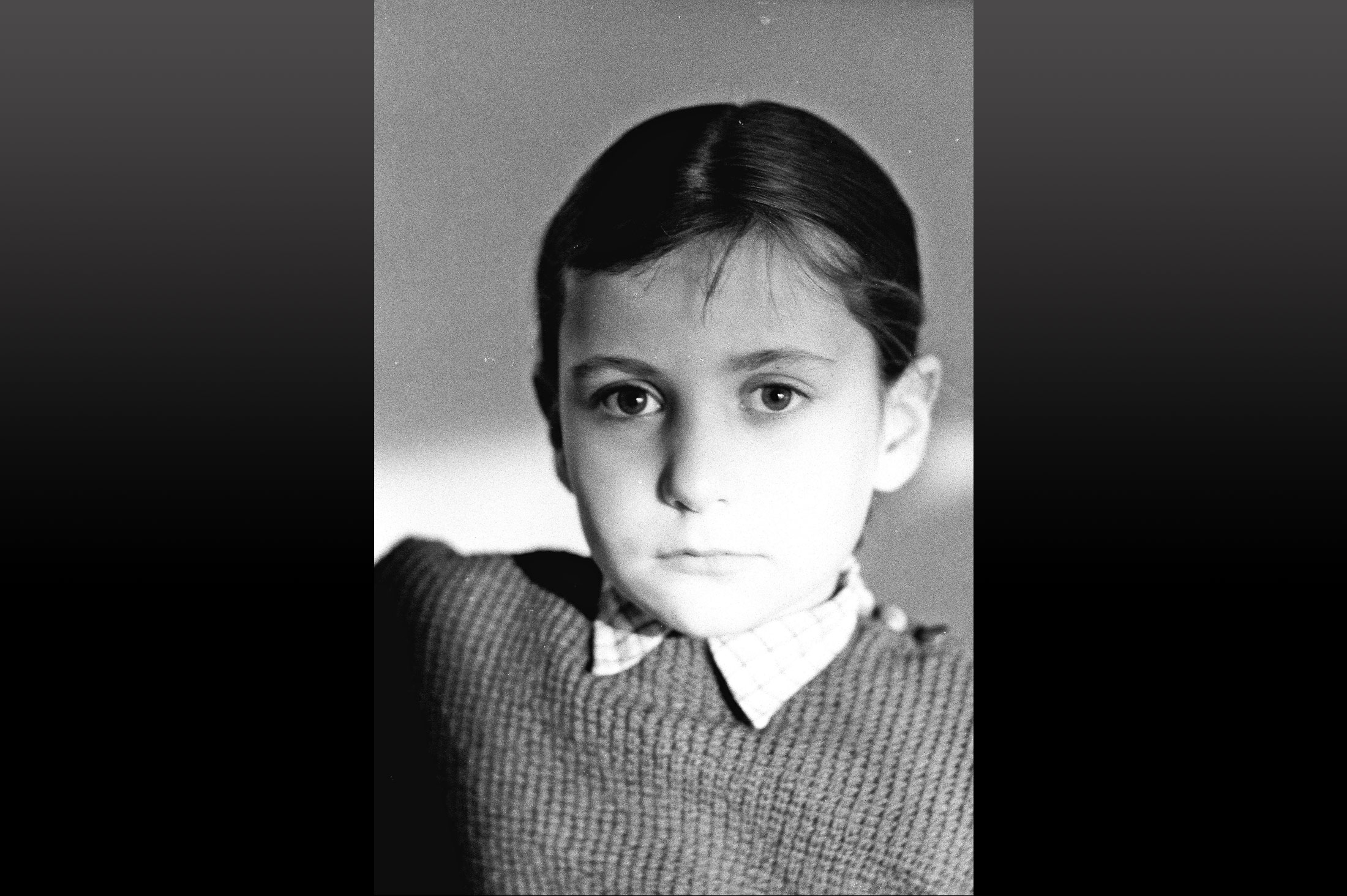

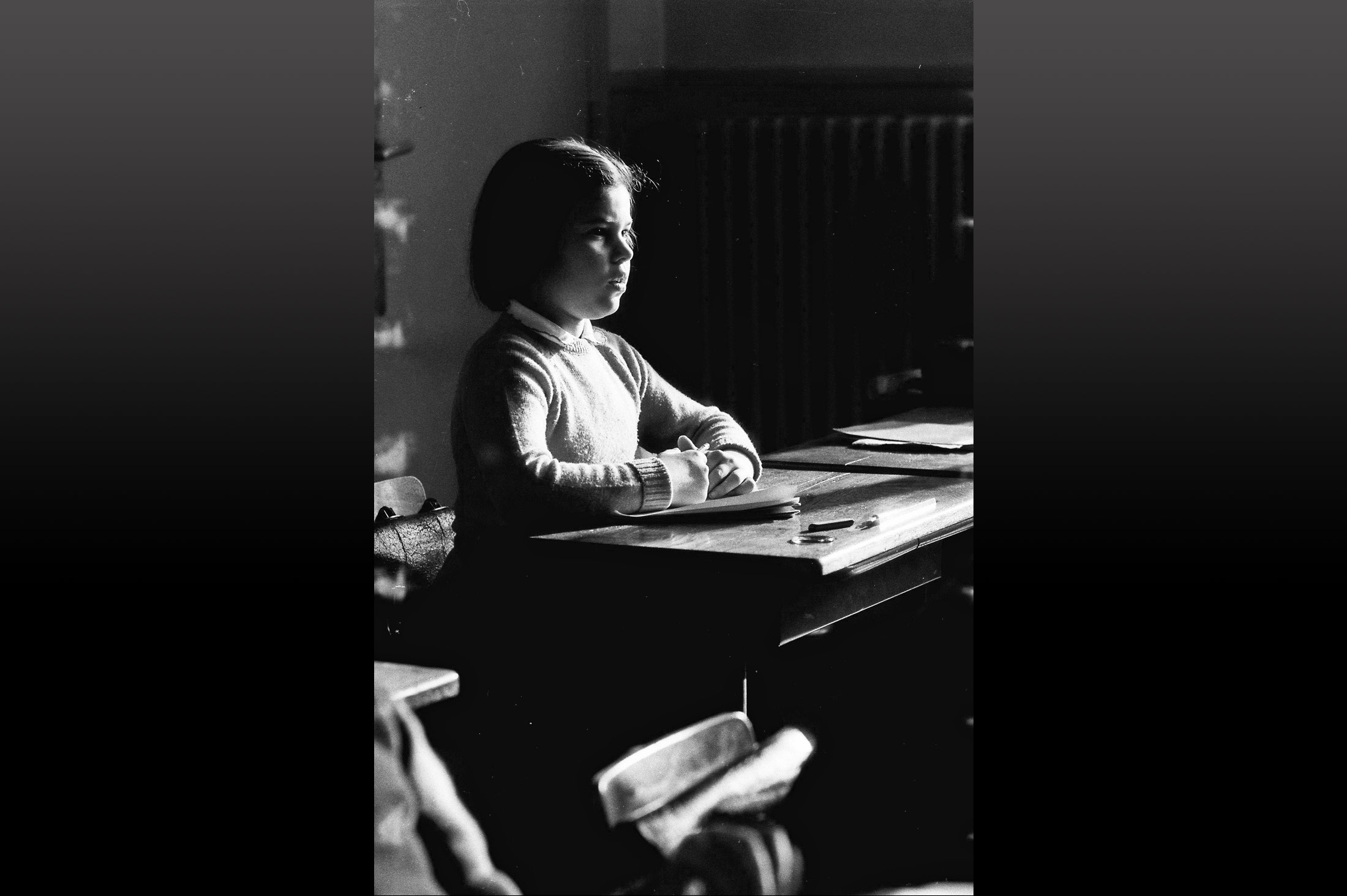

The SHAPE school was at the heart of the purpose-built SHAPE village, which had been hastily assembled in 1951 to house hundreds of employees and their families. General Eisenhower had originally envisioned “an island on the Seine where SHAPE families could work and live together to create a truly coherent international community.” General Le Bigot, SHAPE’s finance minister, instead suggested the 25-acre estate of the Château d’Hennemont, which he poetically said “was like an island in the middle of a sea of green situated in the countryside on the outskirts of St-Germain-en-Laye.” The chateau itself—which dates from 1905 and was occupied by both German and American forces during the Second World War—was to be the first site of the SHAPE school. But the school children were not treated to palatial luxury; in fact, the chateau was initially used as the SHAPE officers’ club and the first classroom was relegated to the chateau’s stables. However, this soon changed.

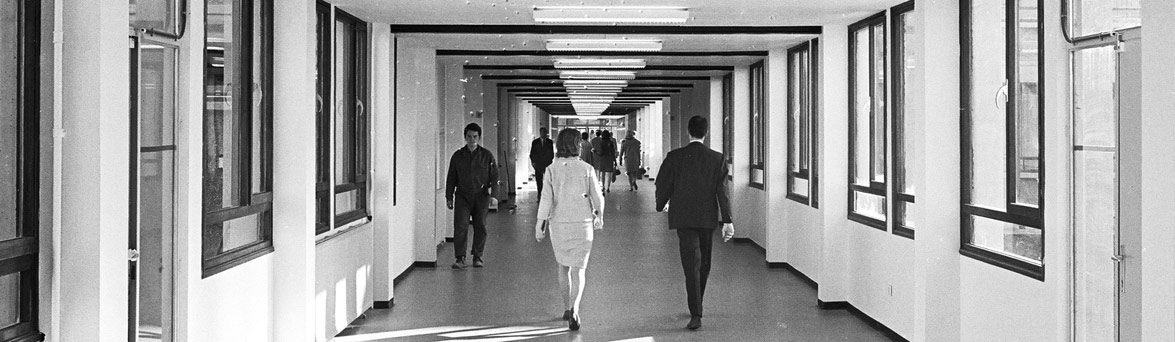

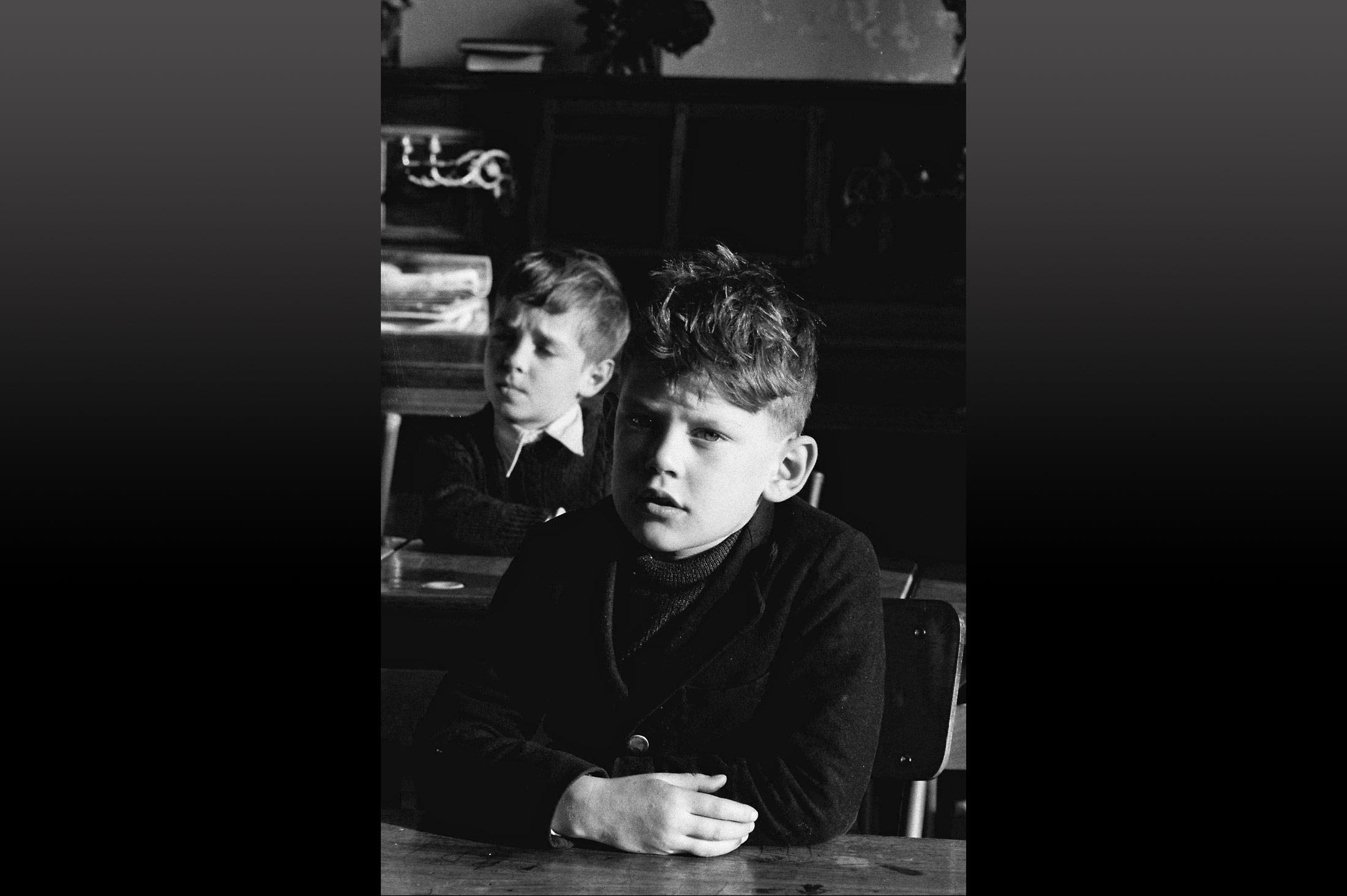

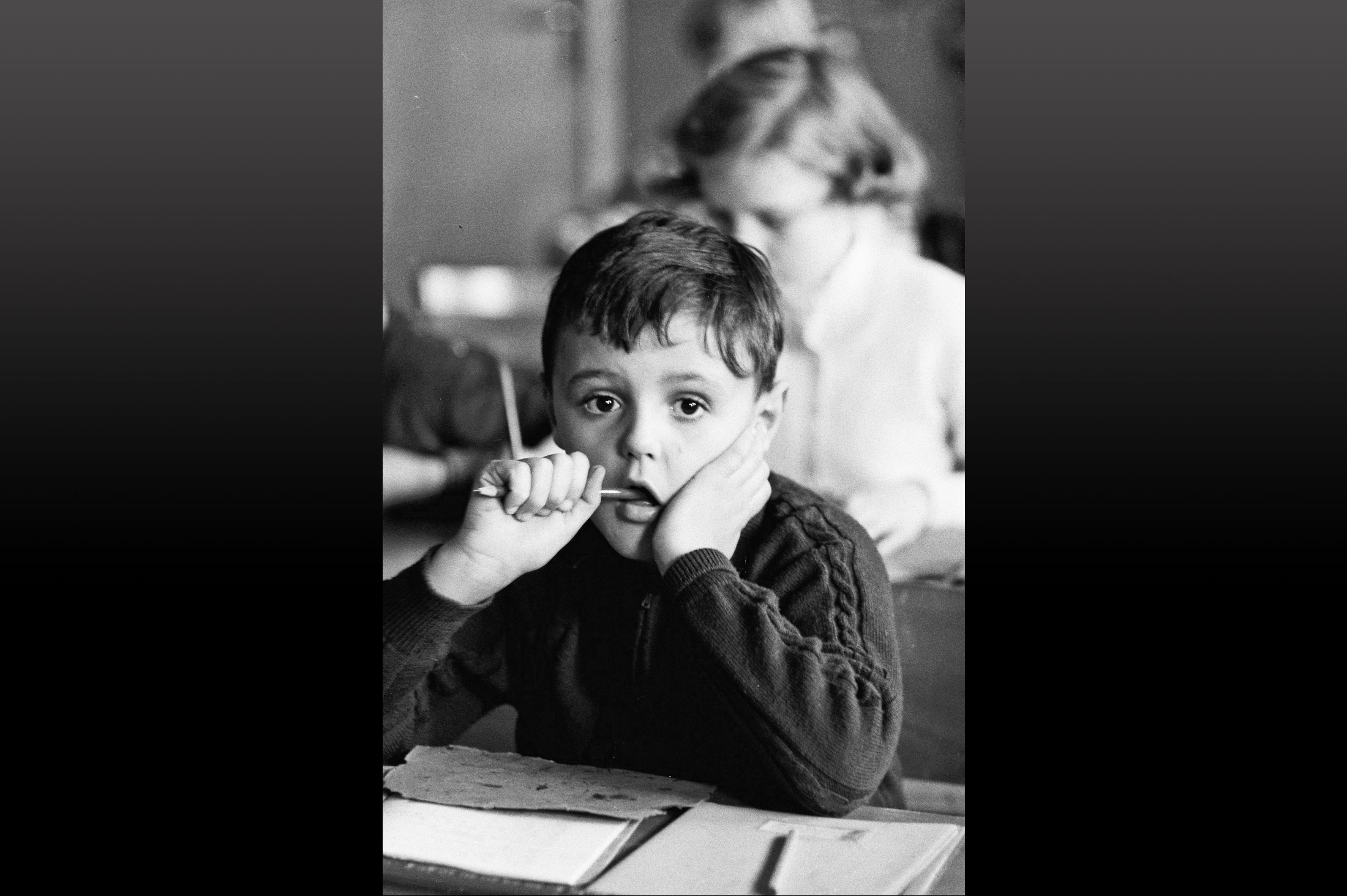

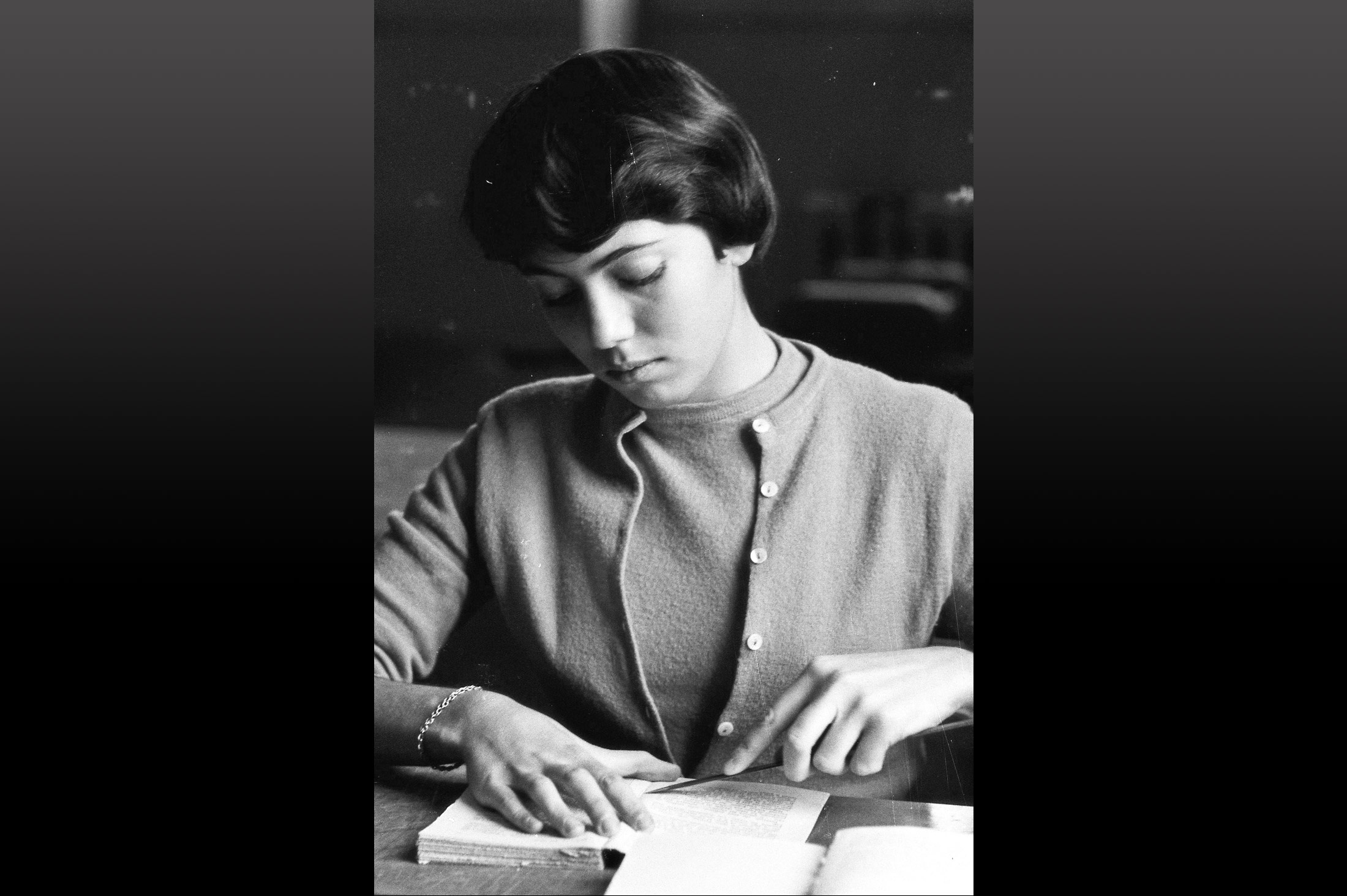

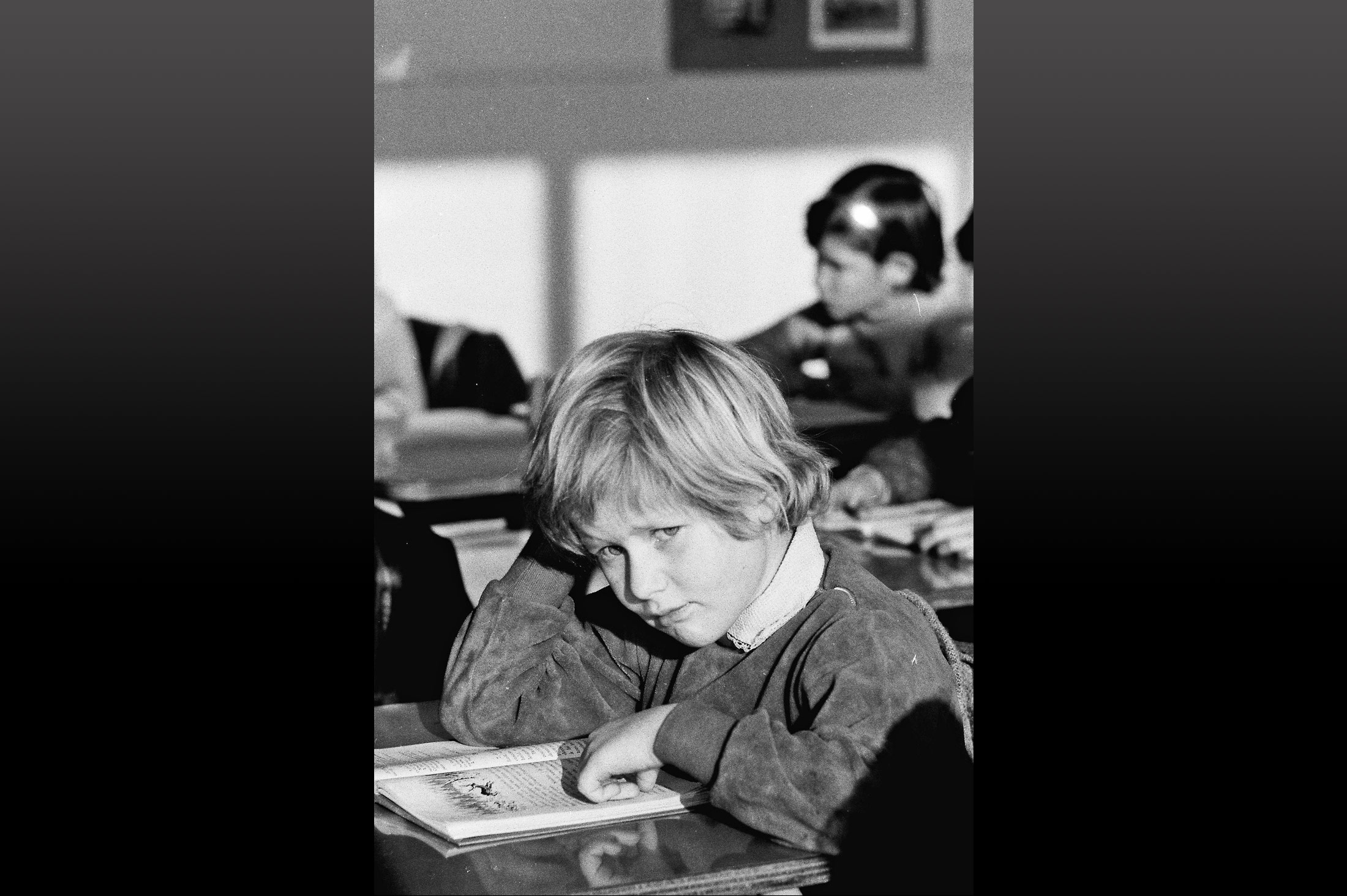

The school officially opened on 18 January 1952, with two teachers and 18 pupils. By October 1952, there were 250 pupils and the school had spread into its own prefab buildings. Growing out of the stables, conditions in the new buildings were far from ideal. Some of the rooms were heated with oil stoves that gave off fumes and the sports facilities were limited. In spite of these humble beginnings, the school continued to grow. Two upper floors of the chateau were taken over as classrooms, then the ground floor became reception rooms, and then the basement was converted into the school kitchen. By 1956, the school had completely occupied the chateau. And by the 1960s, there were 150 staff members and over 1,600 pupils—almost half of whom were not NATO children, but the French children of local residents or the children of foreign families living in Paris.

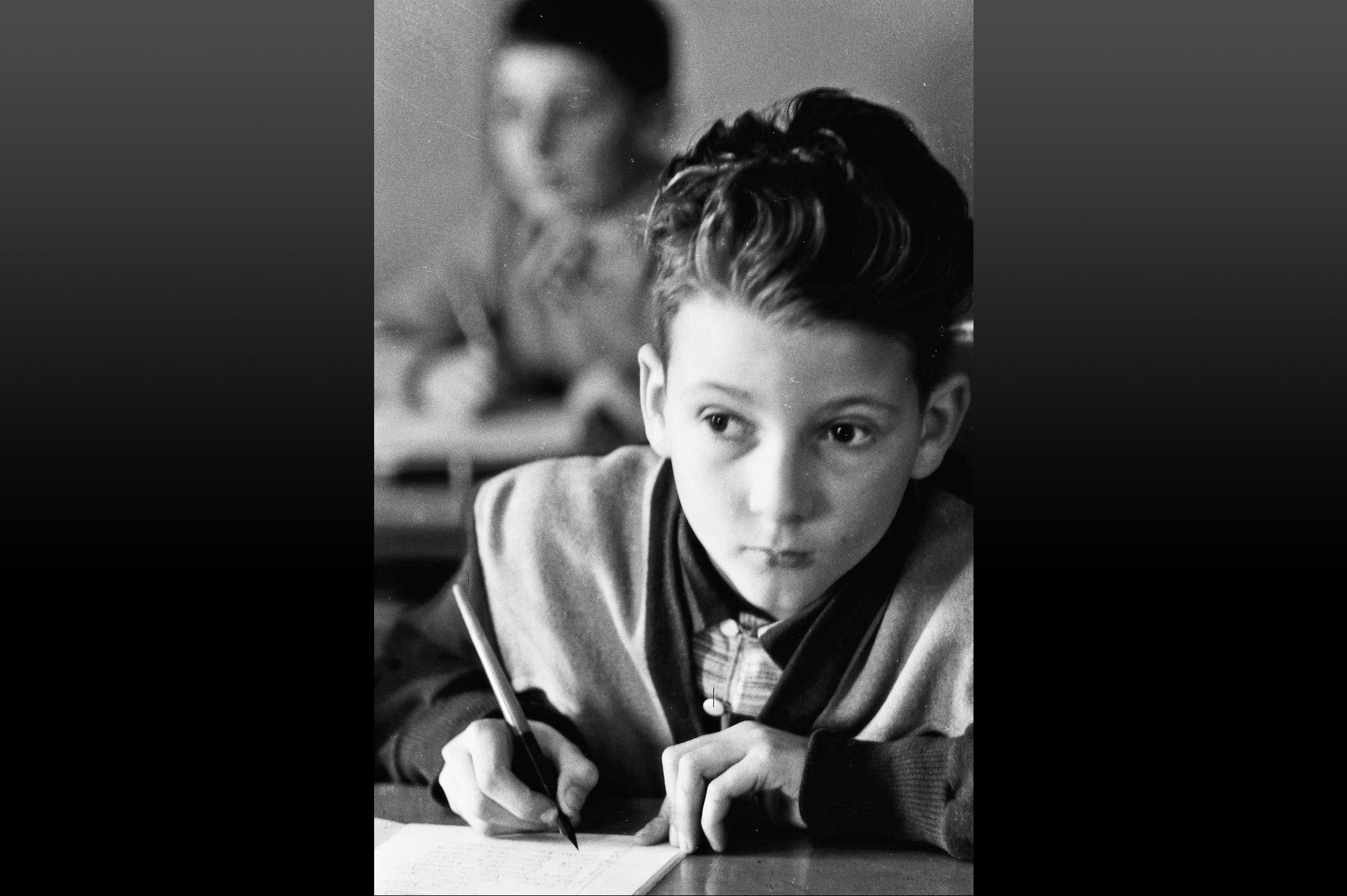

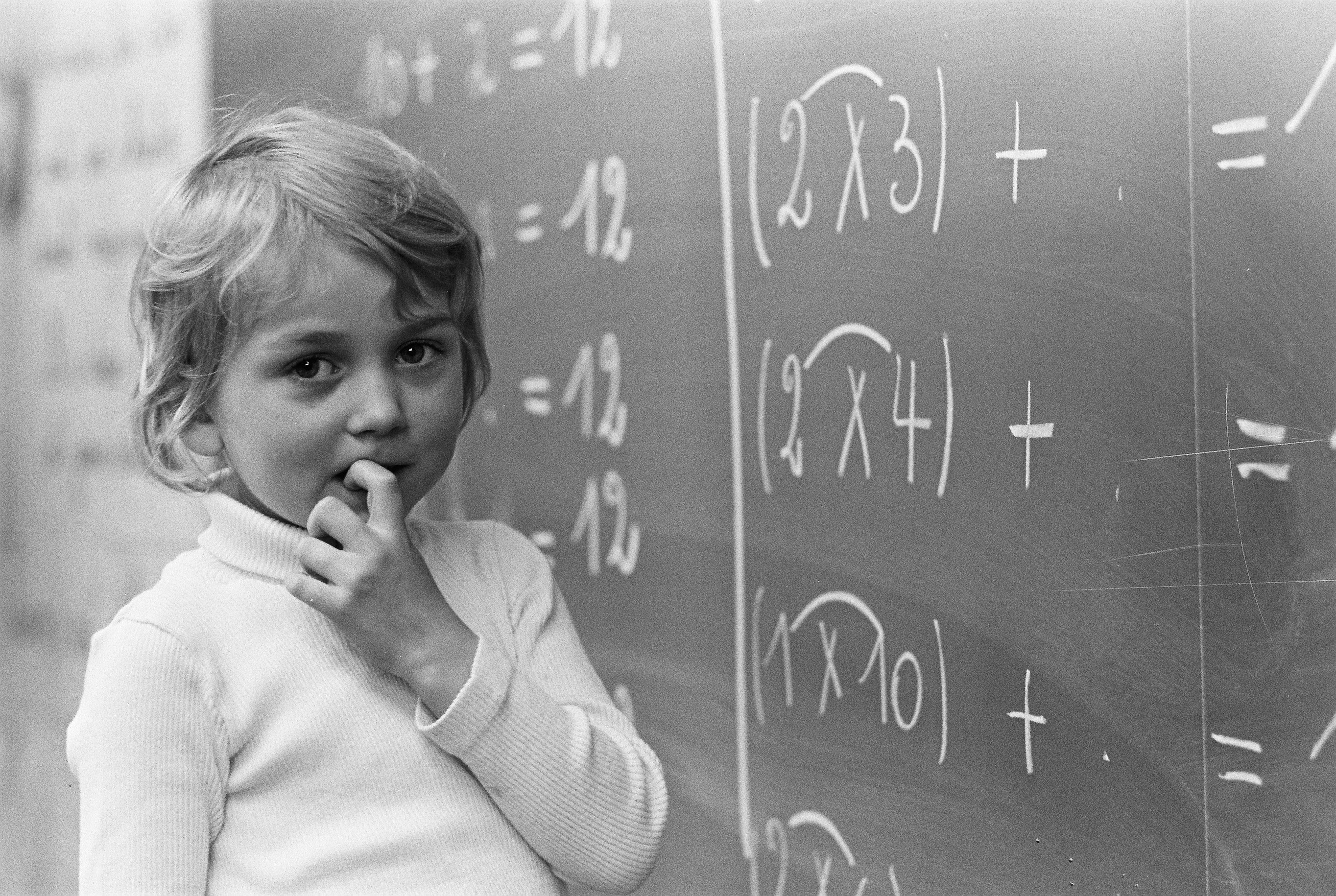

A unique curriculum

The SHAPE school’s first Proviseur, René Tallard, was tasked with building “an establishment characterised by international unity, while preserving the integrity of individual nationalities.” As such, pupils received both a formal French education and instruction in their own language and culture. The school also developed an introductory language course, Français Spécial, which attracted praise from education experts as a “unique and exceptional programme.” While taking Français Spécial, most pupils were able to achieve full French fluency within ten weeks.

As France’s premier international school, the SHAPE school provided preparation for both the French baccalauréat and the International Baccalaureate examinations. Pupils could continue their studies at universities in France, or return to their home countries. According to Tallard, the international mindset provided by the SHAPE school helped its alumni break down cultural barriers when they went on to universities with diverse European student bodies. Ultimately, the SHAPE school’s unique curriculum was designed to “prepare young people for their place in the world which will be different from that of their fathers to a degree we cannot yet measure.”

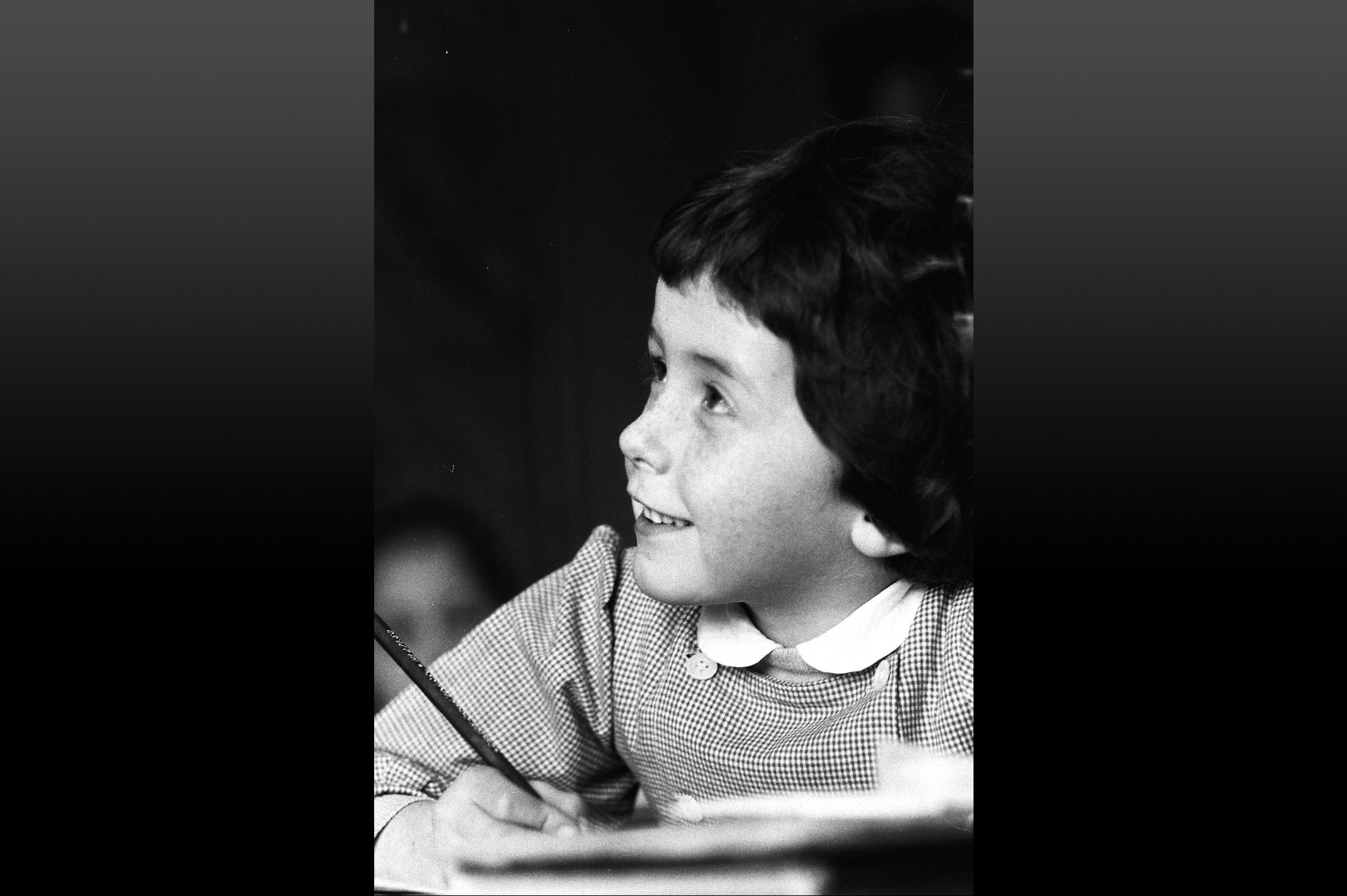

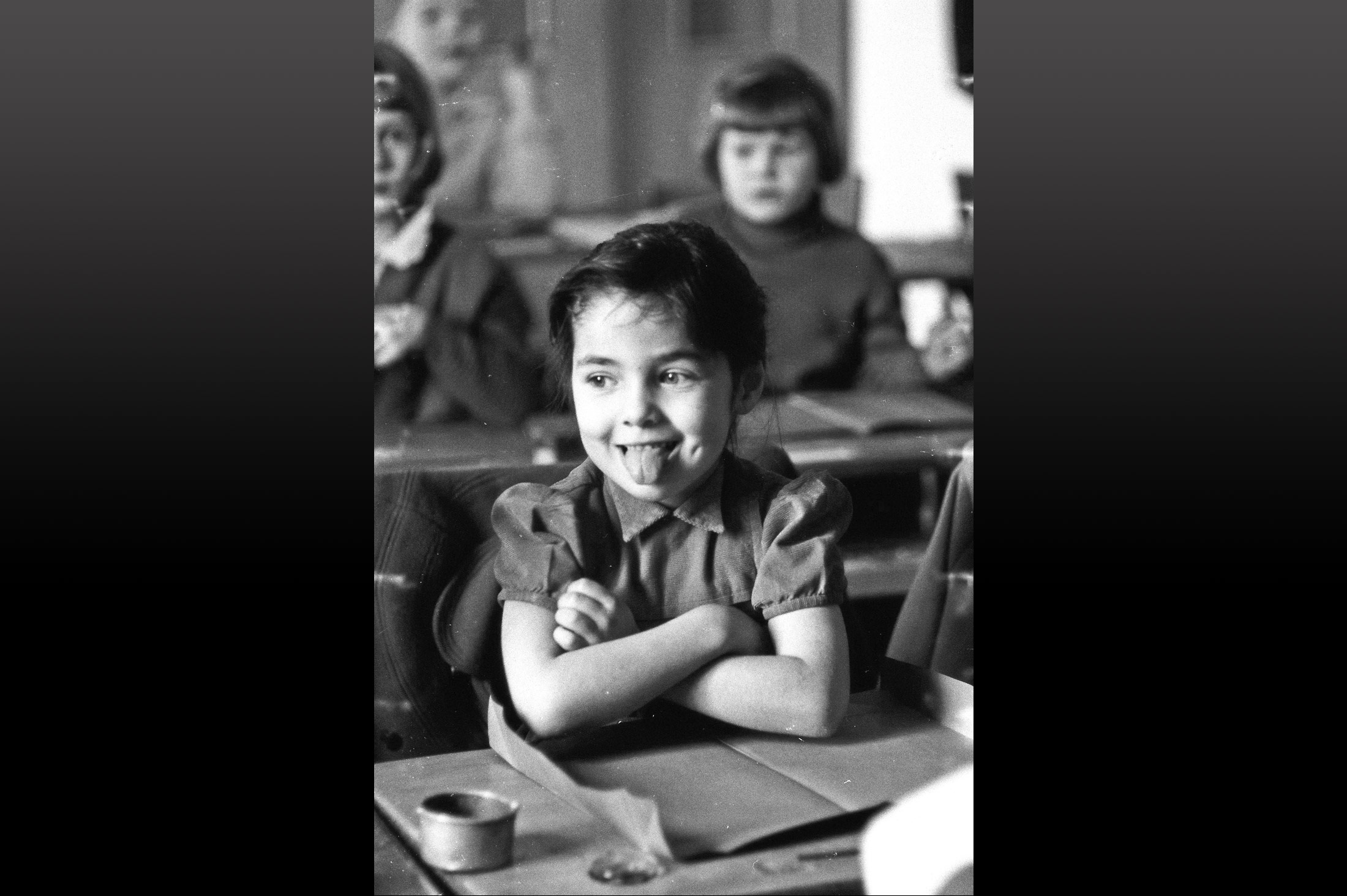

Life at the “Lycée International de l’OTAN”

Outside the classroom, pupils—and their parents—had plenty of opportunities for intercultural exchange. One of the earliest manifestations of cultural differences among children emerged around the question of lunch: “British and American students were quite happy to bring their lunch box to school, but French families expected cafeteria service.” The disagreement was settled by installing lunch rooms on the chateau’s first floor, where pupils could either eat their boxed lunches or have food provided by a communal kitchen.