Read Adenauer’s inaugural speech!

With the help of Minister of Economic Affairs Ludwig Erhard, Adenauer oversaw the West German Wirtschaftswunder or "economic miracle" of the 1950s. It had been triggered by the American Marshall Plan (1948), which provided financial aid to the war-torn European countries that wished to receive it. In the first decade of the Federal Republic, the country's GDP rose by 8 per cent per annum and standards of living doubled. The country rapidly caught up with its Western European counterparts, swiftly becoming an industrial and manufacturing powerhouse. Famous German companies like Volkswagen saw explosive growth, and international trade tied West Germany even more securely into its alliance with the West.

The iconic Beetle

The Volkswagen Beetle became a symbol of West Germany's economic recovery. The year the country joined NATO, in 1955, the one millionth Volkswagen Beetle rolled off the assembly line. To celebrate this milestone, the car was painted gold and its bumpers were studded with rhinestones.

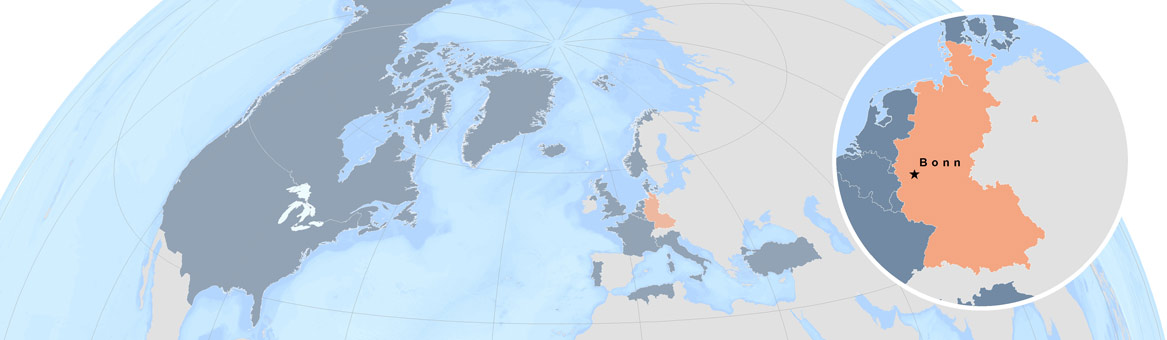

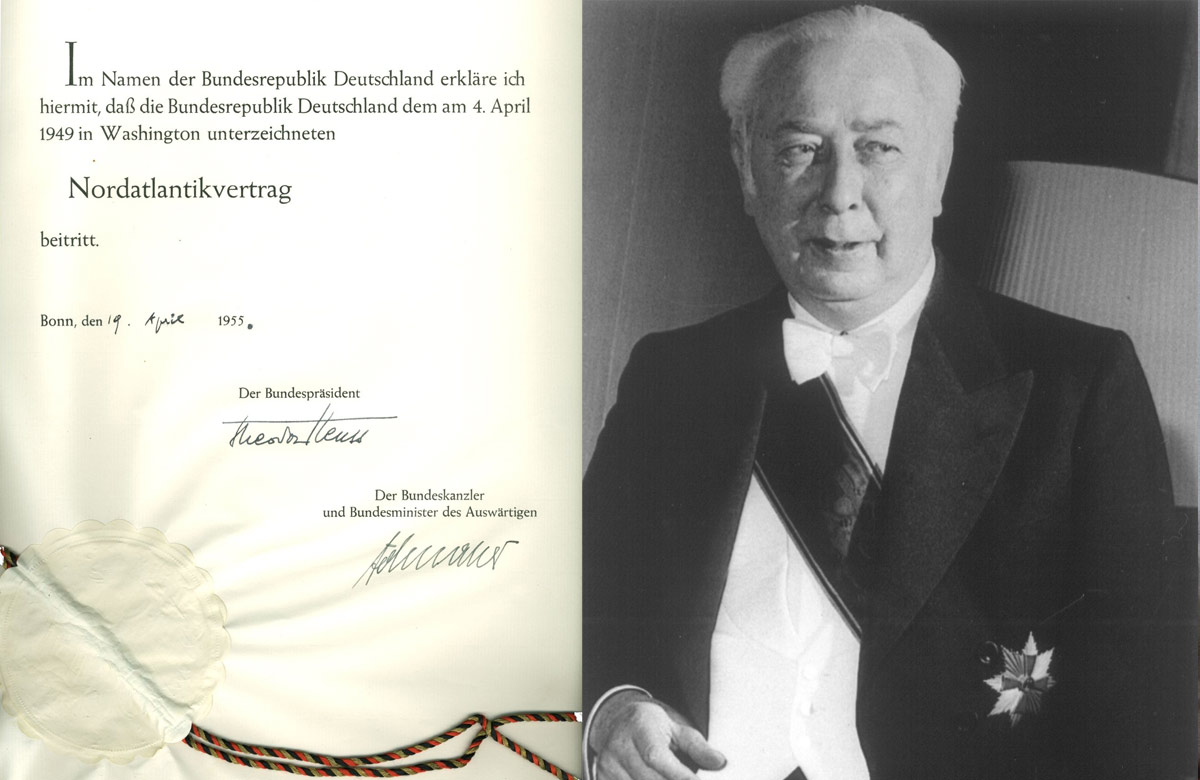

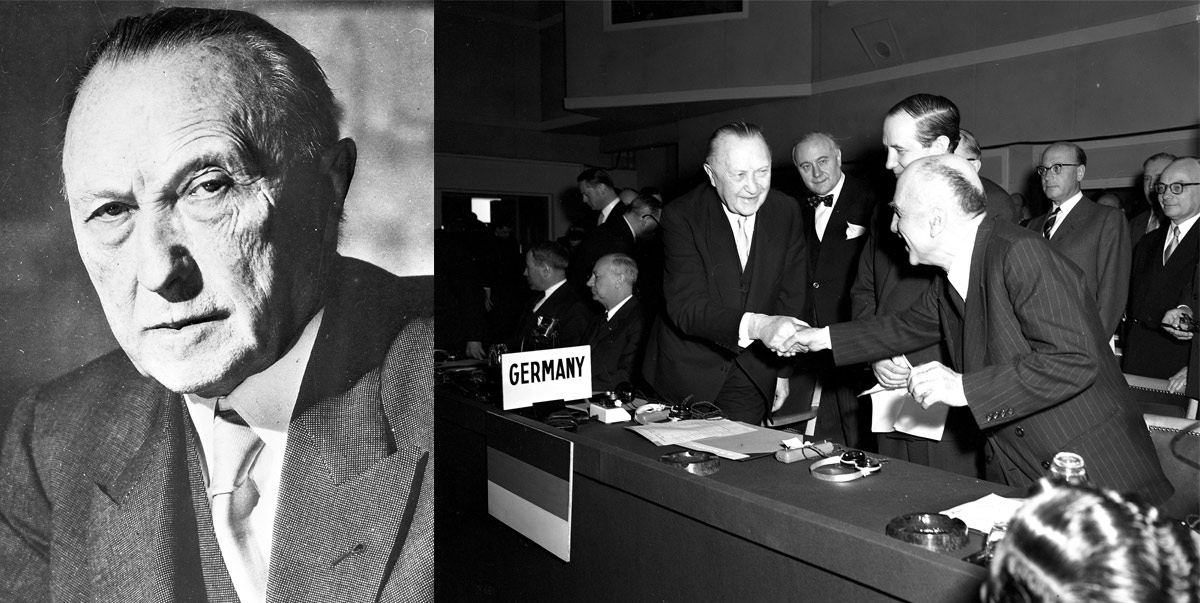

Adenauer's economic and social policies brought West Germany back from total desolation, but the most significant policy decision of his Chancellorship was to choose Western integration over German unification. In choosing to align West Germany with NATO and the Western Allies, Adenauer sacrificed any potential for a short-term reunification with East Germany – a domestically controversial position. His thoughts on this dichotomy were made most clear in a statement he made to the French High Commissioner to West Germany in 1954: "Do not forget that I am the only Chancellor Germany has ever had who preferred the unity of Europe to the unity of his country."

An artist's representation of NATO

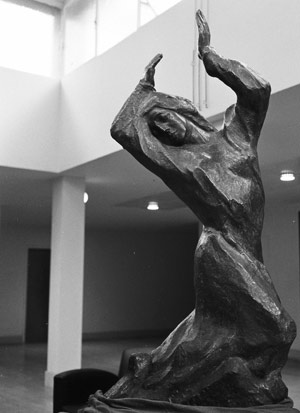

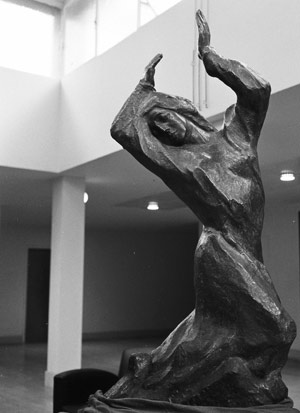

"The praying woman" or

Die Betende was given to NATO on 20 February 1960. Chancellor Adenauer commissioned this work of art from the celebrated German artist Yrsa von Leistner. The main themes of the artist's work revolved around peace, spirituality and memory; this bronze represents NATO's mission of hope and peace, and is displayed at NATO Headquarters. Ysra von Leistner produced other sculptures for international sites such as the Madonna of Nagasaki. One of her more famous works was a bust of the Chancellor, which resides in the Adenauer Haus Museum near Bonn, Germany.

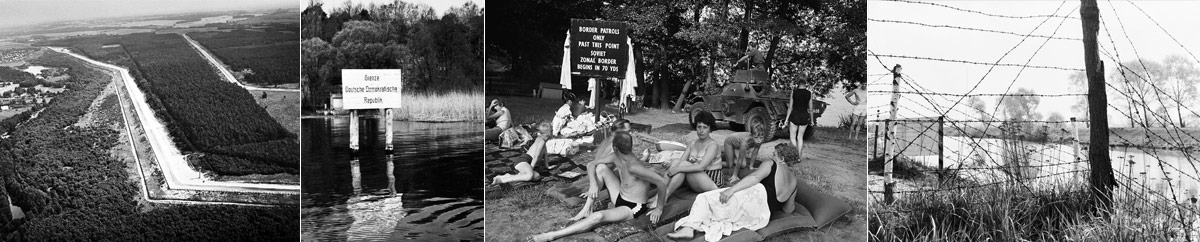

A military bastion

With NATO's decision to engage in a strategy of "forward defence", this meant placing its defences as far to the east in Europe as possible. The Federal Republic of Germany's military role was discussed by planners even prior to its accession (read the document from 1954). NATO's main defence line was first on the Rhine-Ijssel, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Alps. The NATO commander, General Lauris Norstad, was able to move this defence line further east to the Weser and Lech rivers from 1 July 1958 onwards; full forward defence was reached when it was moved a second time in September 1963 to the demarcation of the Iron Curtain itself.

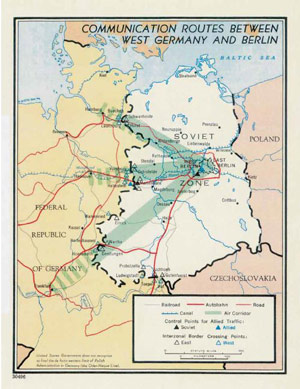

A back-up plan for West Berlin

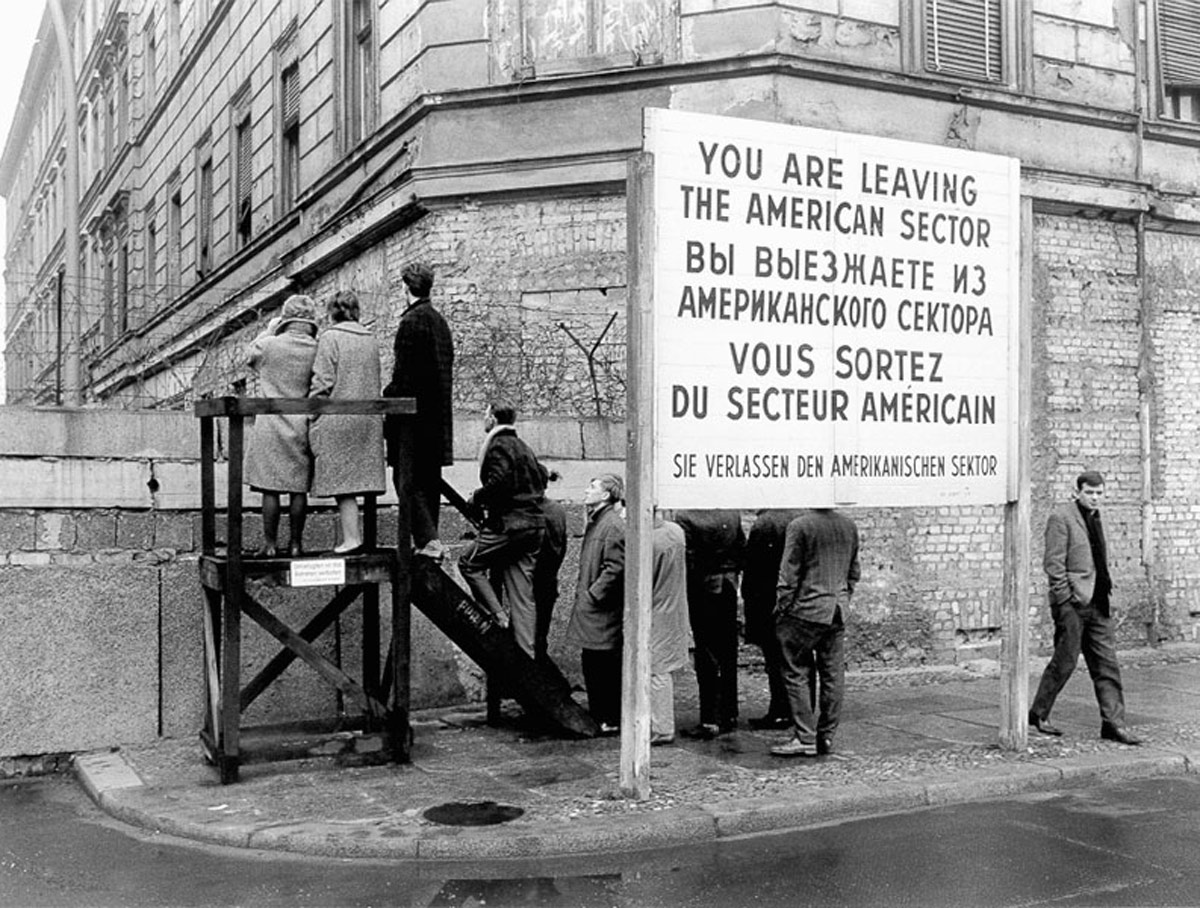

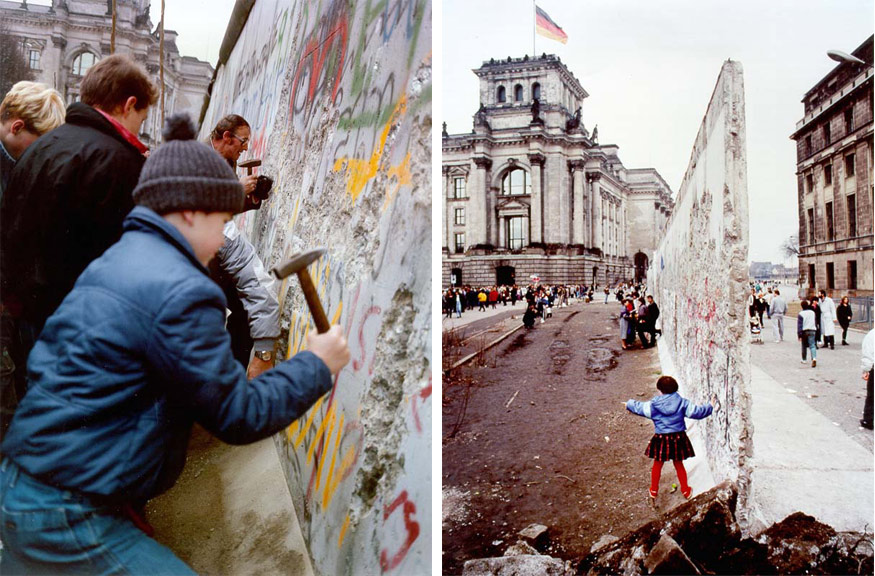

The 1963 line of defence brought NATO Allies as close to Berlin as possible. Berlin had sustained two crises: the

Berlin Blockade (1948) and the crisis that culminated in the construction of the Wall (1961). In 1958 the Soviet leader at the time, Nikita Khrushchev, had issued an ultimatum for Western Allies to exit Berlin. With the city ever more threatened by a Soviet attack, the three Allied powers administrating West Berlin – France, the United Kingdom and the United States – formed a covert military planning staff called LIVE OAK. Its commander was the same American general who assumed the duties of Supreme Allied Commander, Europe (SACEUR) in NATO.

LIVE OAK was charged with protecting Western access to West Berlin by air, rail and road, and did so until the end of the Cold War.

The line of defence was several things: the stationing of hundreds of thousands of troops, numerous commands and headquarters, weapons systems, vast equipment storage facilities and countless military manoeuvres. This was an incredible concentration of military activity in one country; American support was vital and the German contribution was massive. The Bundeswehr could reach a maximum of 500,000 service personnel and was supported by additional civilian defence workers and reservists, with the same numbers maintained until the reunification of Germany; these forces were at the disposal of the Alliance, without any intermediate organisational structure. The Bundeswehr was also a huge contributor to NATO's ground-based air defence system, its combat aircraft, naval forces and, in particular, its naval forces in the Baltic Sea.

In 1957, Gen. Hans Speidel (left), was the first West German officer to hold a NATO position; he became Commander of LANDCENT.

In 1957, Gen. Hans Speidel (left), was the first West German officer to hold a NATO position; he became Commander of LANDCENT.Military personnel and their families from six other Allied countries (Belgium, Canada, France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States) lived and worked alongside German forces and the local population to secure the line of defence. Approximately 400,000 foreign service personnel and almost as many dependents were in West Germany, while there were almost 10,000 in West Berlin alone.

The commands played a key role in the Alliance’s strategy of “forward defence”. Initially, NATO created two military headquarters out of British and American force structures already set up in West Germany: the Northern Army Group (NORTHAG), co-located with the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) in Rheindahlen; and the Central Army Group (CENTAG), co-located with the US Army Europe in Heidelberg. Both came under the command of Allied Forces Central Europe (AFCENT), which was first based in Fontainebleau, France, then in Brunssum, the Netherlands, from 1967 onwards. NORTHAG and CENTAG were decommissioned in 1993, but remained active NATO bases until 2013, when a major restructuring of the NATO Command Structure returned both sites to the German government.

Gen. Johannes Steinhoft (left) with NATO Secretary General Manlio Brosio in 1971. Gen. Steinhoff was one of several German generals to serve as Chairman of NATO's Military Committee.

Gen. Johannes Steinhoft (left) with NATO Secretary General Manlio Brosio in 1971. Gen. Steinhoff was one of several German generals to serve as Chairman of NATO's Military Committee.Many other Allied commands were established in West Germany, and Allied forces such as the quick reaction multinational force – or Allied Command Europe (ACE) Mobile Force – were hosted on German territory (its headquarters were in Mannheim). The NATO E-3A base for the Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft was set up in Geilenkirchen in 1980 and is still there today, as is the NATO School established in 1953 in Oberammergau in the Bavarian mountains. The Federal Republic of Germany also participated in NATO’s integrated air defence system – NADGE – that has been operational since 1971. With all of these major NATO bases and forces in Germany, German generals were able to hold some of the leadership positions in NATO commands or take on responsibilities within the broader NATO structure.

Exercises, exercises, exercises…

For the two superpowers – the Soviet Union and the United States – exercises were a display of intent and capability. During the Cold War, West Germany was the scene of hundreds of exercises; in 1982 alone, 85 major NATO exercises were held on German soil. They were a combination of NATO-led and national exercises, all working toward the same objective: demonstrating the political will and military means to defend against an adversary. American support was essential, and showing that the United States would be present was vital to the credibility of the Alliance’s deterrence and defence. Exercise Operation Big Lift (22-23 October 1963) was a prime example of that: 14,500 US troops were flown to Europe from Texas in record time to demonstrate rapid reinforcement in an emergency. In 1969, the REFORGER (REturn of FORces to GERmany) exercise series started and continued through to 1993; every year, REFORGER demonstrated the United States’ commitment and ability to reinforce Allied forces stationed in West Germany. Other Allies held similar exercises in the Federal Republic of Germany.

In 1975, when NATO considered the Warsaw Pact to be conventionally superior, it launched the Autumn Forge exercise series. These exercises helped to reinforce the Alliance’s defence and deterrence and fell under the “SACEUR 3R programme” (Readiness, Reinforcement and Rationalisation) initiated by General Alexander Haig when he became the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). Each year, some 20-30 exercises were conducted by NATO commands and national headquarters across Western Europe, from Norway to Turkey, under the one single umbrella of Autumn Forge, helping reinforce synergies between them. Exercise Autumn Forge 1980 is caught below on camera.

Watch the film entitled “Four days in Autumn”!

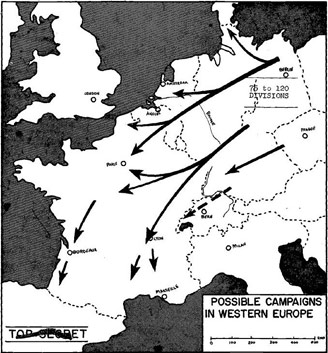

NATO Intelligence reports of possible Soviet military campaigns into Western Europe, 1953 (

NATO Intelligence reports of possible Soviet military campaigns into Western Europe, 1953 ( Berlin was a special case during the Cold War. Although the city was deep within East German territory, it was administered by the four powers (France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics – USSR) that had governed Germany after the Second World War. As the Cold War heated up, Berlin was often used as a pressure point by the Soviets, who hoped to leverage their position encircling the city in their favour. The NATO Allies, for their part, used Berlin as a display of determination and unity, showing that even this disconnected city would not be abandoned. Sadly, there were

Berlin was a special case during the Cold War. Although the city was deep within East German territory, it was administered by the four powers (France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics – USSR) that had governed Germany after the Second World War. As the Cold War heated up, Berlin was often used as a pressure point by the Soviets, who hoped to leverage their position encircling the city in their favour. The NATO Allies, for their part, used Berlin as a display of determination and unity, showing that even this disconnected city would not be abandoned. Sadly, there were  The Volkswagen Beetle became a symbol of West Germany's economic recovery. The year the country joined NATO, in 1955, the one millionth Volkswagen Beetle rolled off the assembly line. To celebrate this milestone, the car was painted gold and its bumpers were studded with rhinestones.

The Volkswagen Beetle became a symbol of West Germany's economic recovery. The year the country joined NATO, in 1955, the one millionth Volkswagen Beetle rolled off the assembly line. To celebrate this milestone, the car was painted gold and its bumpers were studded with rhinestones. "The praying woman" or Die Betende was given to NATO on 20 February 1960. Chancellor Adenauer commissioned this work of art from the celebrated German artist Yrsa von Leistner. The main themes of the artist's work revolved around peace, spirituality and memory; this bronze represents NATO's mission of hope and peace, and is displayed at NATO Headquarters. Ysra von Leistner produced other sculptures for international sites such as the Madonna of Nagasaki. One of her more famous works was a bust of the Chancellor, which resides in the Adenauer Haus Museum near Bonn, Germany.

"The praying woman" or Die Betende was given to NATO on 20 February 1960. Chancellor Adenauer commissioned this work of art from the celebrated German artist Yrsa von Leistner. The main themes of the artist's work revolved around peace, spirituality and memory; this bronze represents NATO's mission of hope and peace, and is displayed at NATO Headquarters. Ysra von Leistner produced other sculptures for international sites such as the Madonna of Nagasaki. One of her more famous works was a bust of the Chancellor, which resides in the Adenauer Haus Museum near Bonn, Germany.

© Ursula Stock

© Ursula Stock