The goal, the preservation of peace, is also Denmark’s, in deep accord with the ardent desire

and old tradition of the Danish people.”

From Gustav Rasmussen’s speech at the signing ceremony of

the North Atlantic Treaty, 4 April 1949

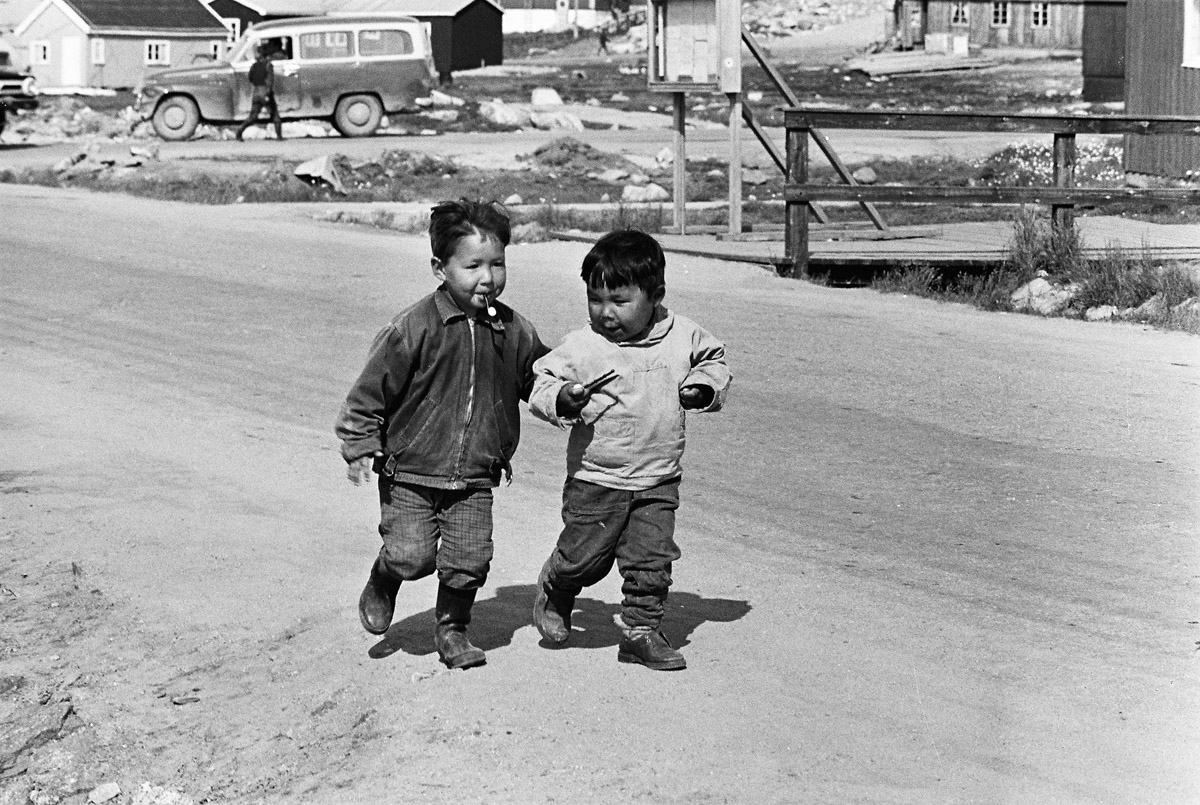

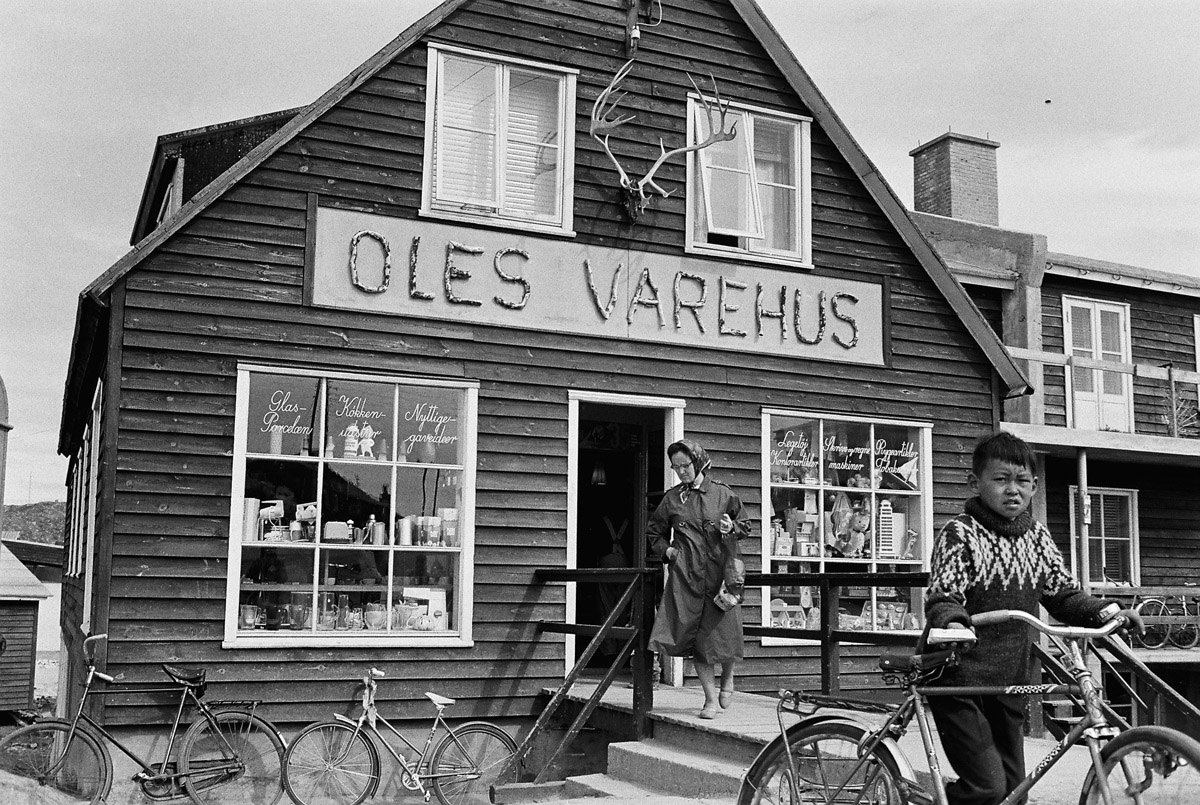

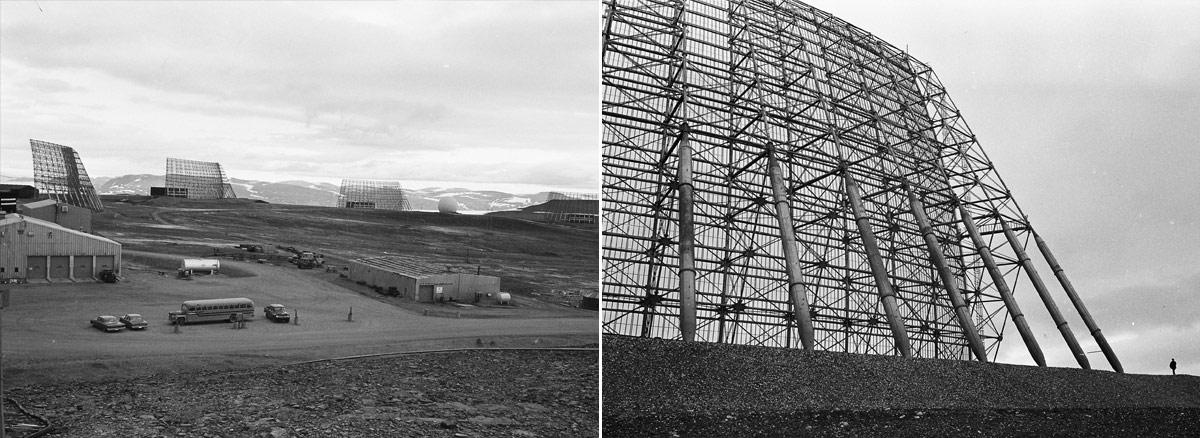

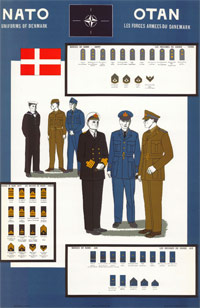

Better known for the magic of Lego and Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, the Kingdom of Denmark, although geographically small, is a strategic giant. A bridge between the north and south of Europe, the gatekeeper of the Baltic Straits and the key holder to Greenland and the Faroe Islands, Denmark is a key strategic player for Western Allies. It opens up the way to the Baltic Sea and the Arctic, while providing an essential stepping stone between Europe and North America.

In 1949, turning its back on decades of strict neutrality, the Danish Folketing (the Danish Parliament) voted largely in support of NATO membership. Throughout the Cold War, the tradition of neutrality occasionally permeated the country’s defence and foreign policies and sometimes manifested itself during discussions within the Alliance. However, this former neutral power of approximately four million inhabitants at the time had a vital role to play and, later in the post-Cold War period, it proved to be one of the Alliance’s most reliable and active members.

The Nordic link

Denmark is intrinsically linked to its Nordic neighbours – Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. They share centuries of history, having either occupied each other’s territories at some point in time, signed agreements to strengthen economic cooperation, developed cultural links, shared strong democratic values and, in particular, a culture of consensus-building and consultation that transpires in their daily life. Therefore, it is no surprise that talks on a Scandinavian defence agreement emerged in the 1930s, and again in the 1940s. However, the two world wars severely rocked the certainties that had driven the foreign and defence policies of these countries, i.e., neutrality as a watertight security guarantor, so they were keen to consider other solutions. The First World War showed the failings of the League of Nations to keep the peace and the Second World War clearly illustrated that neutrality was a weak shield against occupation.

Denmark’s Nordic neighbours

Finland shared a huge border with the Soviet Union. During the Second World War, Scandinavian cooperation and the lack of Western support had resulted in losses – territorial and human – so the logical alternative was to opt for friendly relations with the Soviet Union. Although there had always been mutual suspicion between the two, conflict was averted.

Iceland feared being occupied by Nazi Germany during the Second World War, so when the British temporarily occupied the country then withdrew to use their forces on the continent, the void made them rethink their policy of neutrality. On 1 July 1941, Iceland signed an agreement with the United States that allowed the stationing of American forces throughout the hostilities. Iceland became a founding member of NATO in 1949.

Similarly, Norway had a tradition of neutrality and, after being occupied by Nazi Germany during the Second World War, sought alternative policies. It also became a founding member of NATO.

Sweden was militarily armed throughout the Second World War and, this combined with Nazi Germany’s lack of interest, enabled the country to avoid combat. It continued its policy of neutrality and was consequently opposed to having any relation with NATO whatsoever. It proposed a defence pact to Denmark and Norway, which would stop them from collaborating with Western Allies. Both turned it down since it would render them neutral without providing sufficient military support, something the Second World War had proved to be an unviable situation for them.

Composed of 800 or so islands, with Greenland in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and the Faroe Islands off the northern coast of Scotland, Denmark was geo-strategically exposed. Following five years of Nazi occupation, Denmark positioned itself as a non-aligned state prepared to play the role of bridge-builder between East and West. However, during the war a strong resistance movement developed, the spirit of which remained a powerful undercurrent to Danish society. As such, Denmark displayed a very different approach to foreign and defence policy in 1949. This new approach can be summed up in the slogan:

NEVER AGAIN A NINTH OF APRIL

The slogan was adopted by the country’s main political parties: the Social Democrats, the Moderate Liberals and the Conservatives – 9 April 1940 was the day Nazi Germany launched its assault on Denmark and Norway. The alternatives to a NATO solution were few and far between: either neutrality or total disarmament, with the consequences that implied in times of war. The Folketing supported NATO membership and its support remained stable. Interestingly, during the Treaty negotiations of the future North Atlantic Alliance, Iceland linked its membership to that of Denmark’s and Norway’s so as to maintain a degree of unity among Nordic countries. In 1952, this Nordic link took on the form of the Nordic Council: a body for inter-parliamentary cooperation, initiated and presided by the Danish Prime Minister, Hans Hedtoft.

Isolated neutrality or the North Atlantic Treaty?

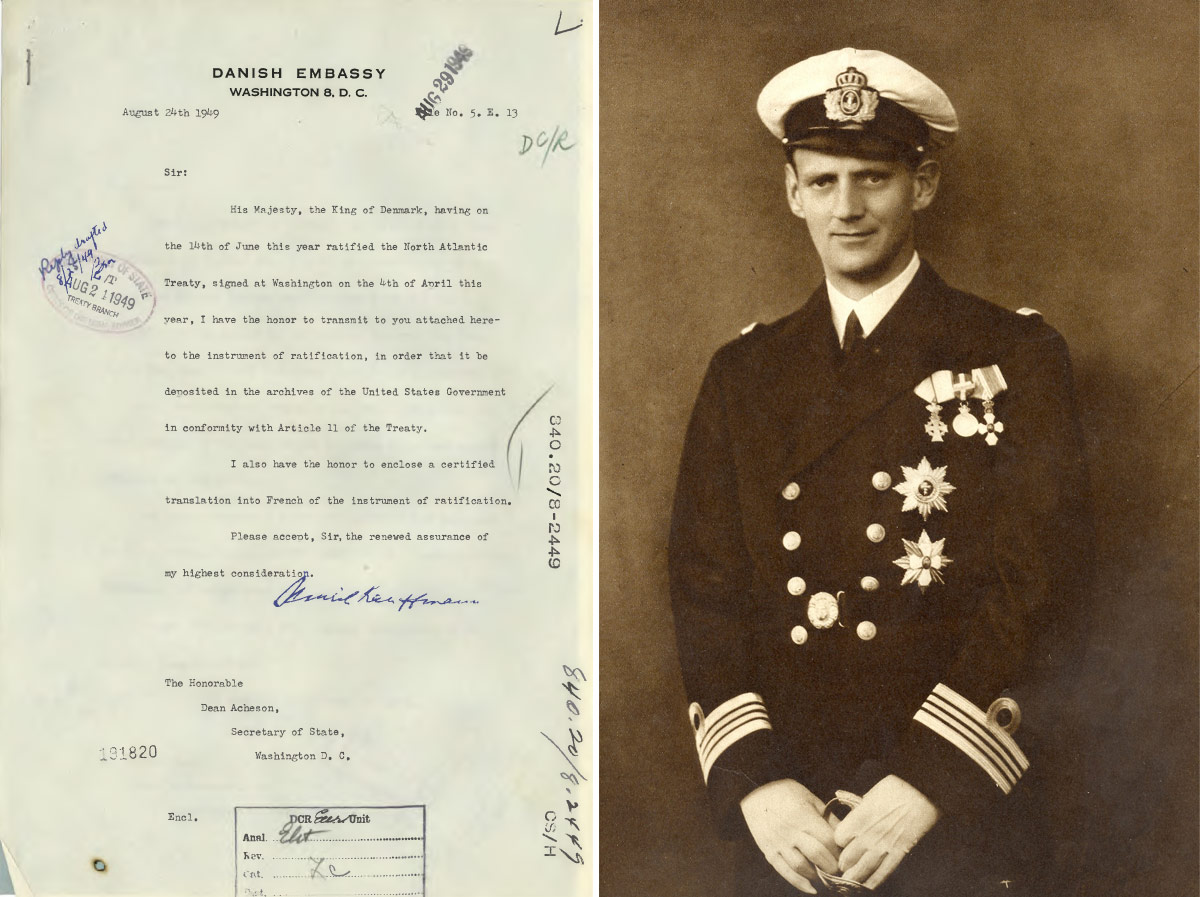

Foreign minister Gustav Rasmussen signed the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949 on behalf of Denmark, even though he was an apprehensive signatory. The main drive behind Denmark’s role as a founding member came from the Prime Minister, Hans Hedtoft. A former member of the Danish resistance movement during the Second World War, he was alarmed by the Communist coup in Czechoslovakia and pushed for NATO membership. For Hedtoft, there was no hesitation: the choice was between isolated neutrality and the North Atlantic Treaty.