Origins

My country and NATO

Italy and its NATO Allies in 1949

(Left) Two posters glorifying the importance of European unity and (right) two Marshall Plan posters designed by Italian artists.

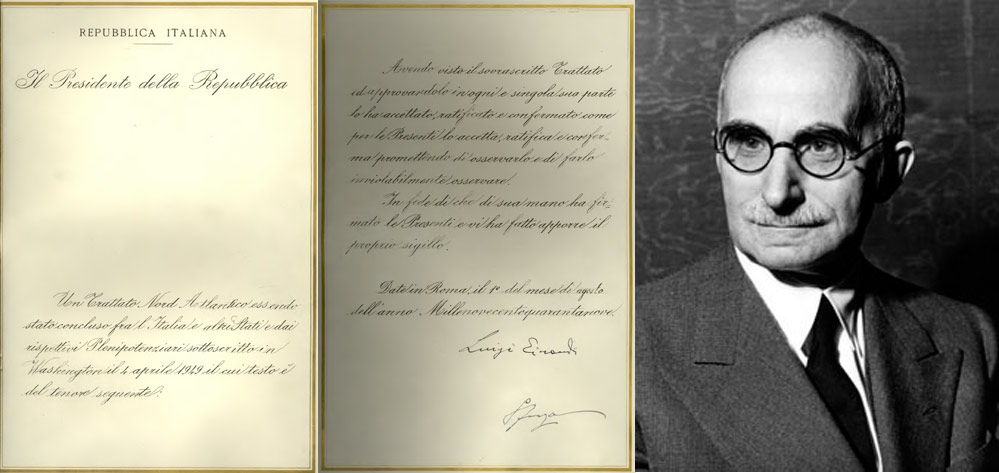

The Instrument of Accession signed by the President of the Republic, H.E. Mr Luigi Einaudi, on 1 August 1949 in Rome

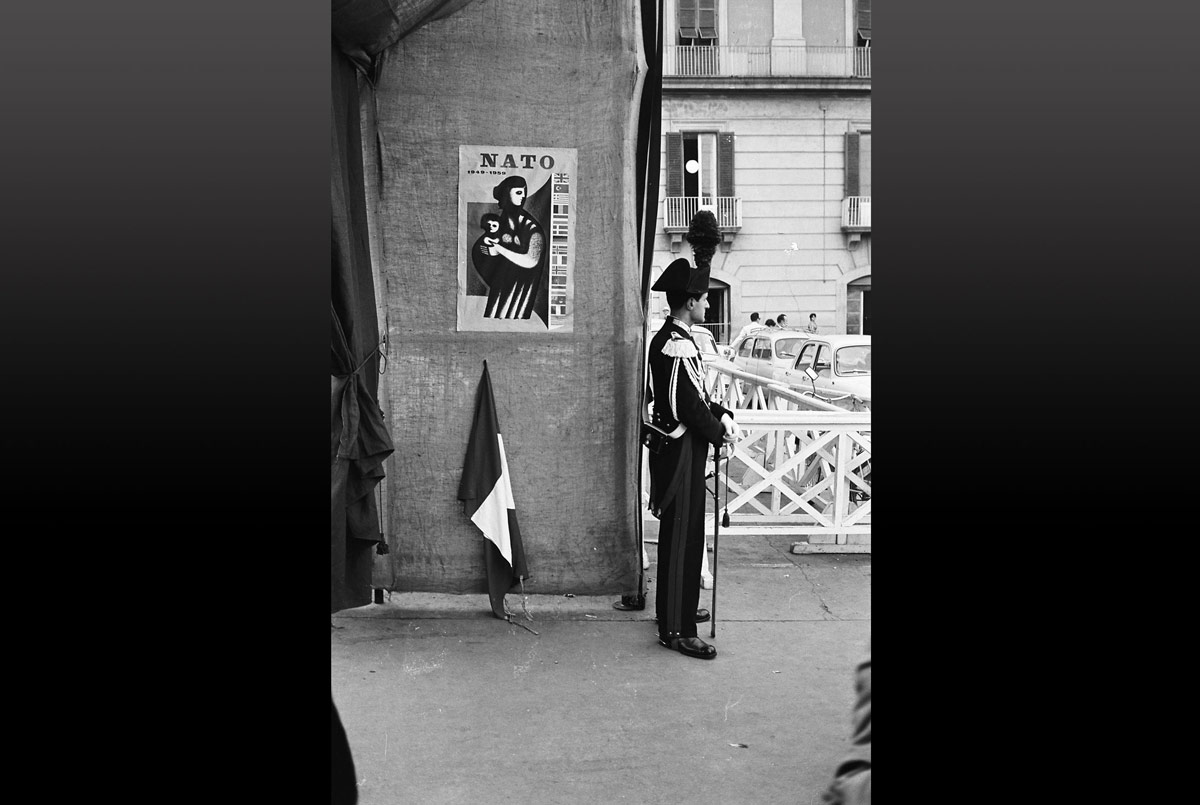

On NATO's 10th anniversary in 1959, an exhibition was organised, Piazza del Plebiscito, in Naples.

Military equipment, photos, posters and films were exhibited and leaflets were handed out.

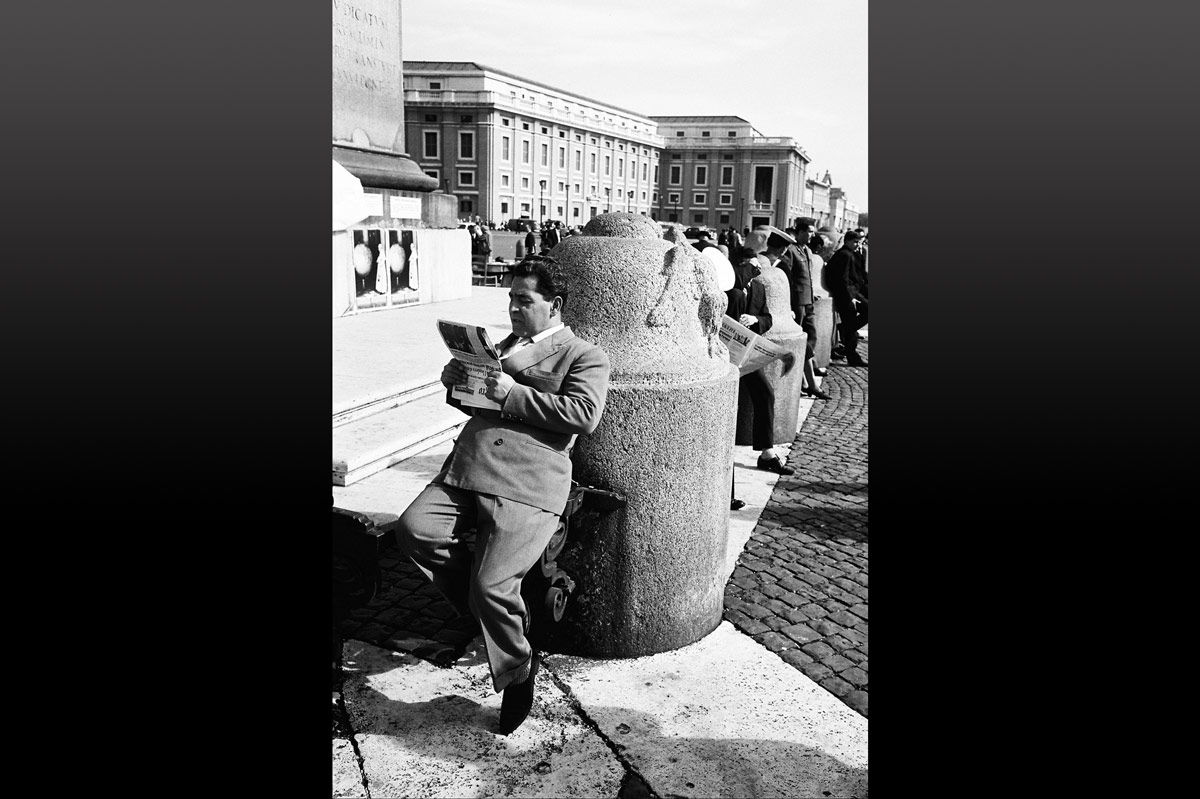

There was always one or several people on the ground to answer questions.

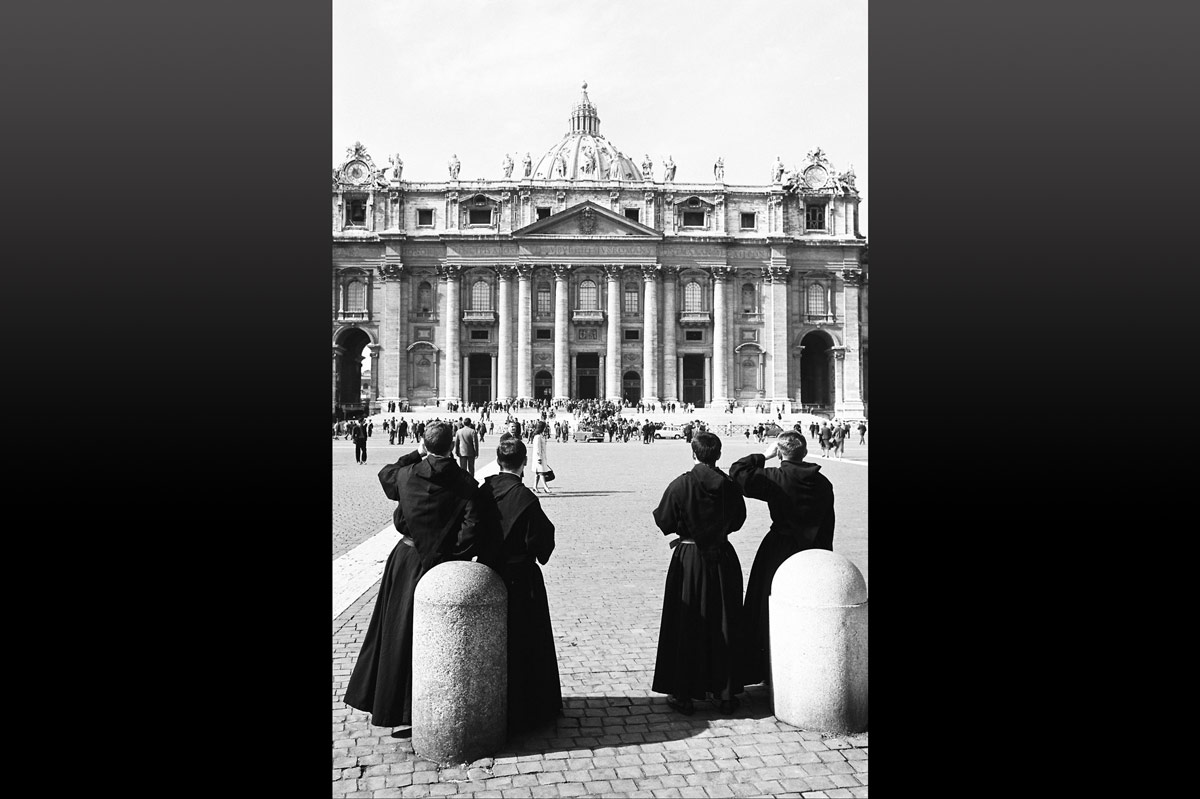

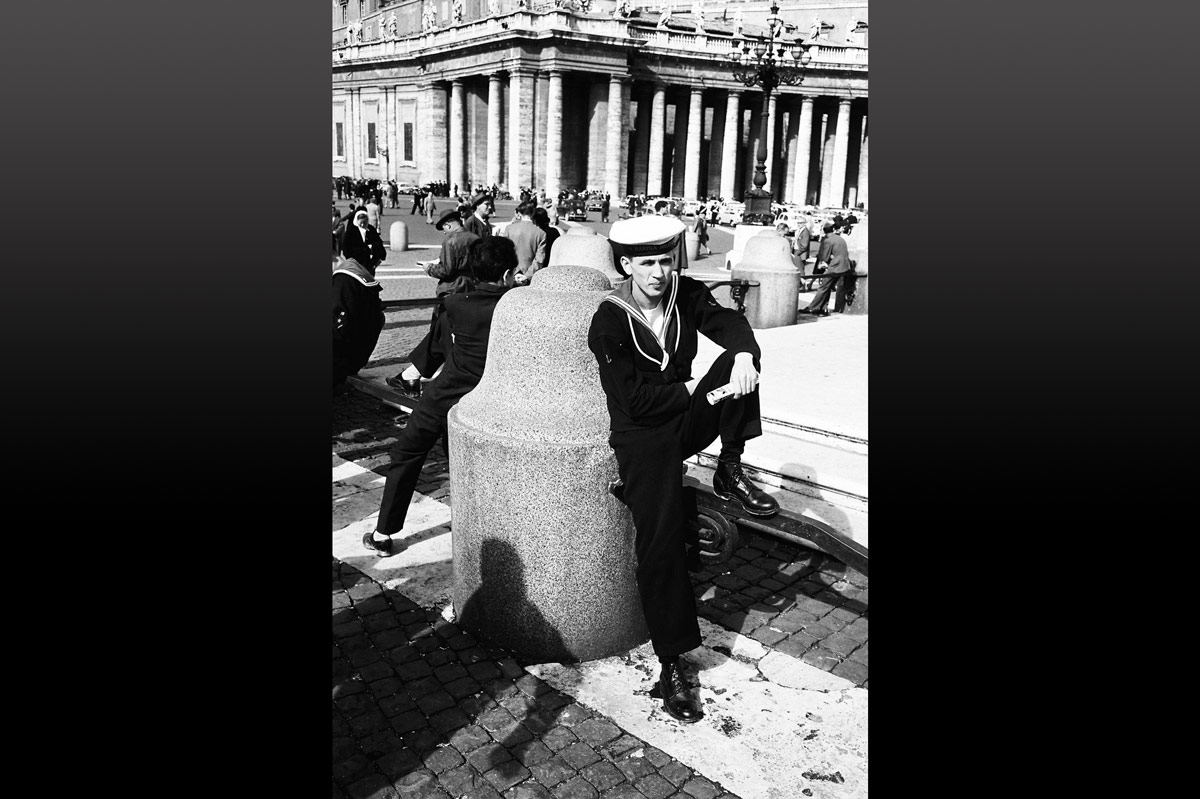

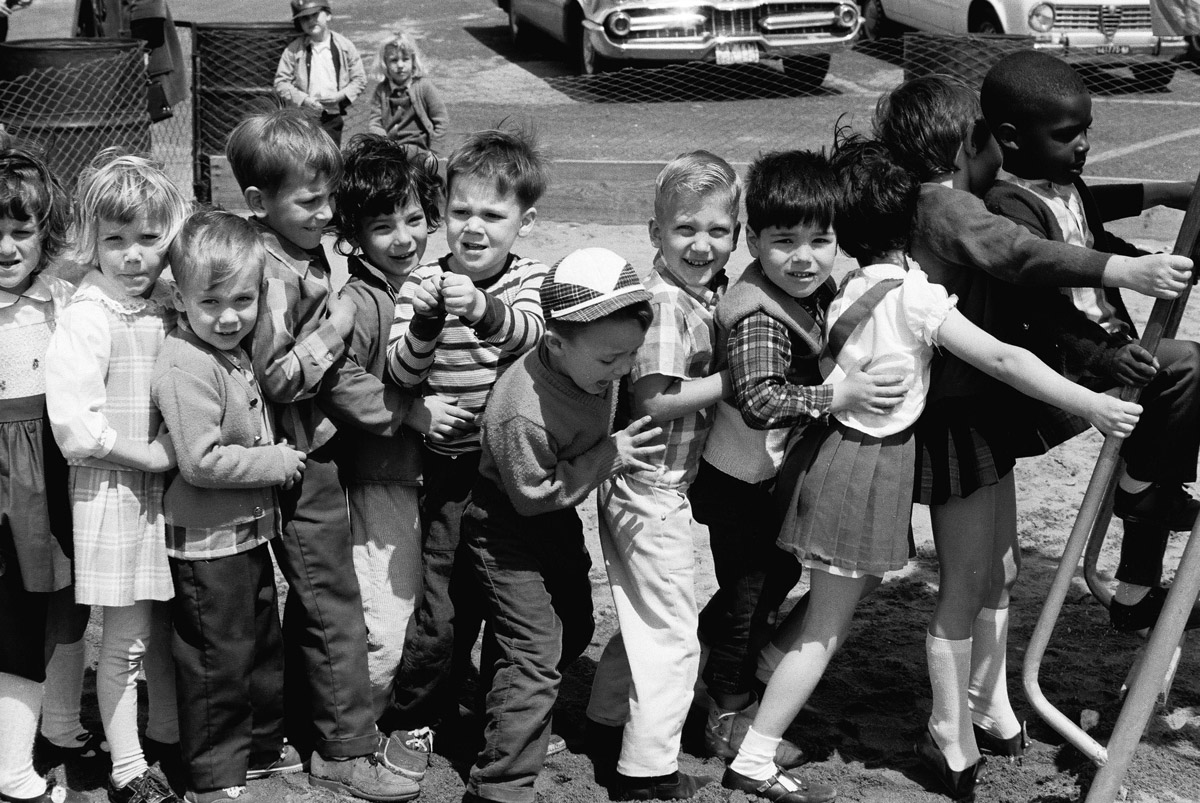

And people from many different backgrounds keen to learn more about the Alliance.

NATO films explaining the Organization and its missions were very popular...

...and the more shaded parts of the exhibition were too!

The exhibition was set up in one of Naples' main squares...

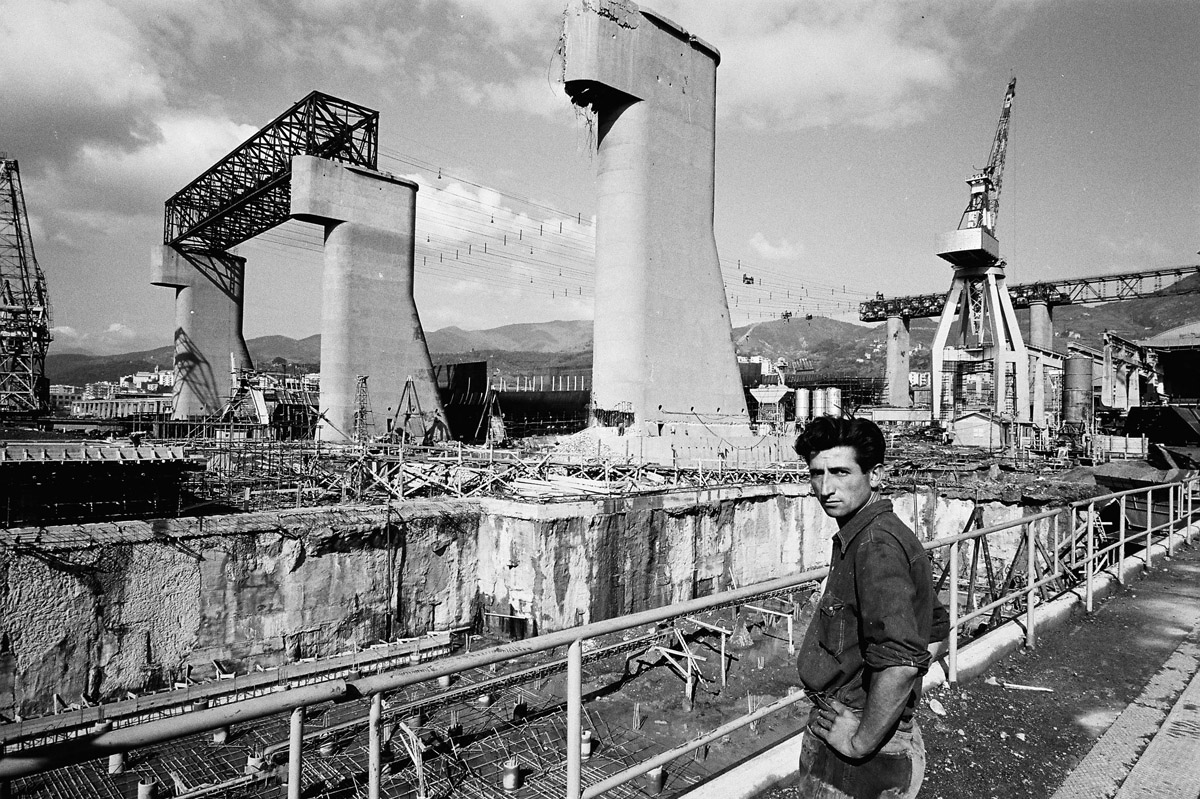

...and spread across to the port from where the public could embark on one of the vessels anchored in the bay.

This was a good way of helping the local public understand how Italy contributed to NATO.

Judging by the number of cars, the exhibition was a popular venue.

Flags at the entrance of the main exhibition were used to identify NATO member countries.

A Carabiniere in full dress guards the entrance, standing next to a 10th anniversary poster.

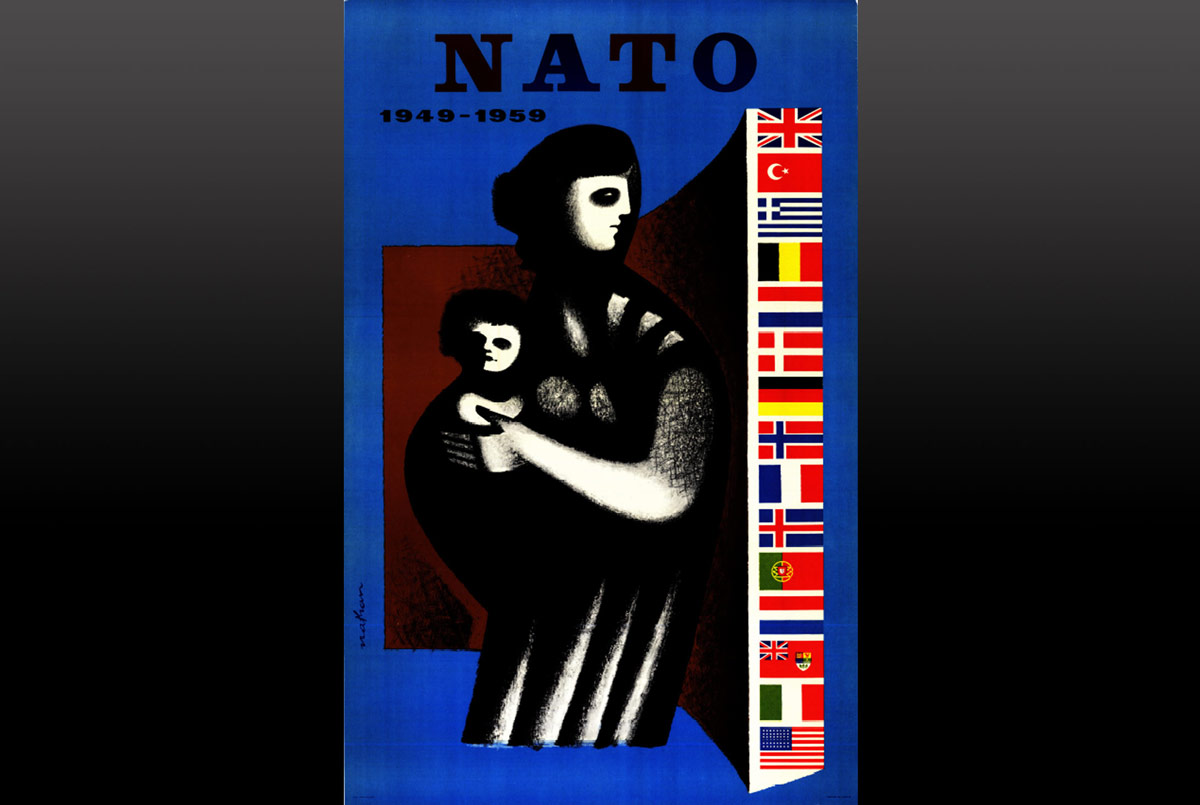

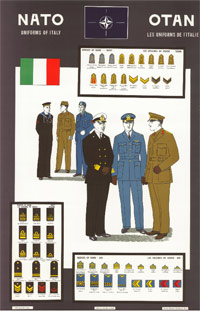

A colour version of one of the 10th anniversary posters produced at the time.

AFSOUTH in its new permanent headquarters in 1954.

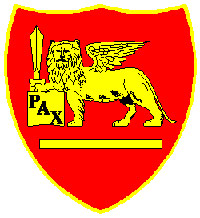

The Command’s emblem: the Lion of St. Mark, can be seen on the pillar.

The Lion is an ancient symbol revered throughout the Mediterranean.

During the Cold War, AFSOUTH defended southern members of NATO, protected sea lanes of communication and acted as a deterrent to Soviet expansionism in the region.

Security was tight at the headquarters.

Passes were checked as you went in ...

...and once you were inside too.

The command employed local inhabitants...

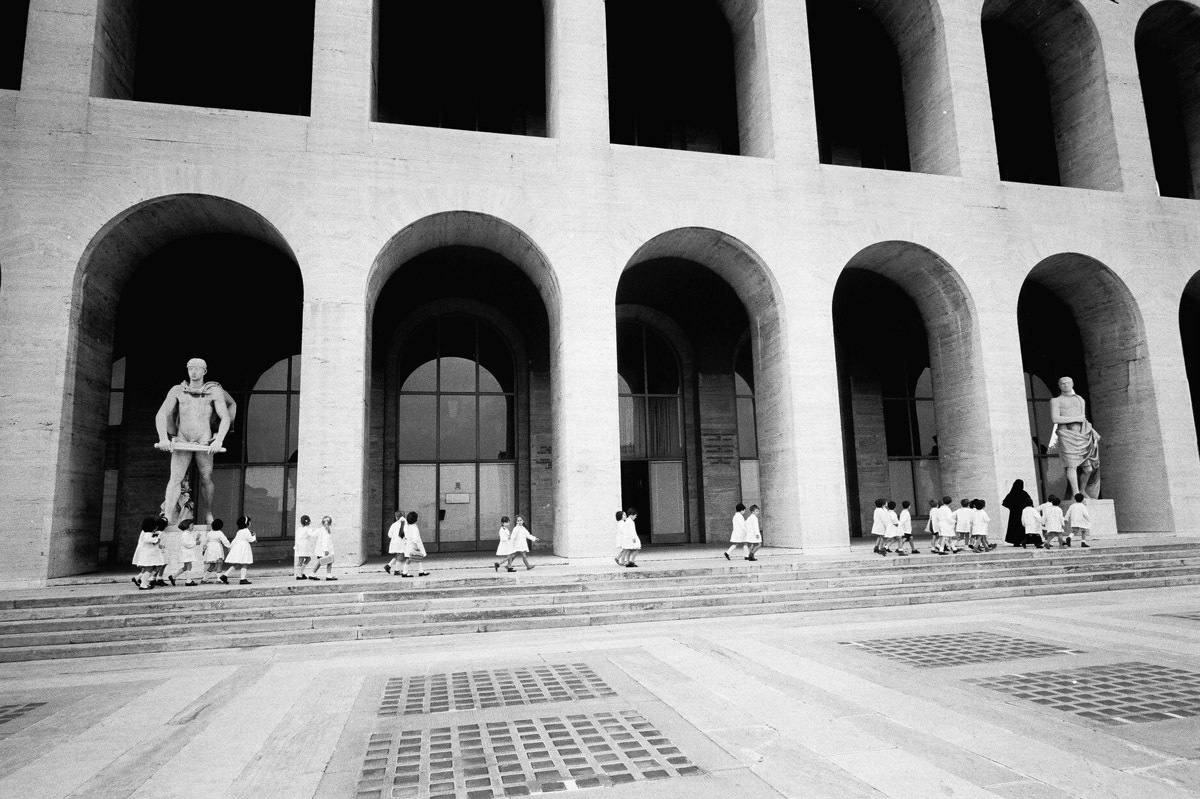

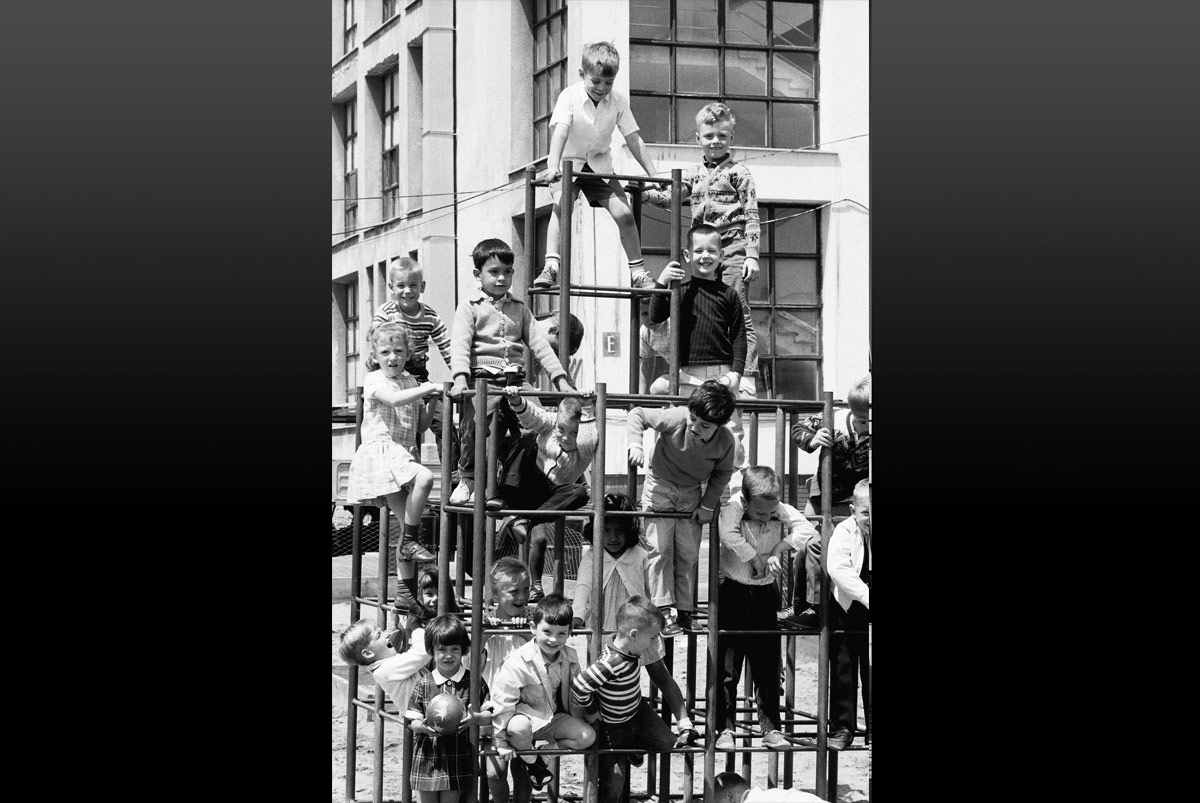

...and provided a school and a nursery for NATO staff.

The hoola hoop was trendy in the playground at the time...

...and the climbing frame good fun.

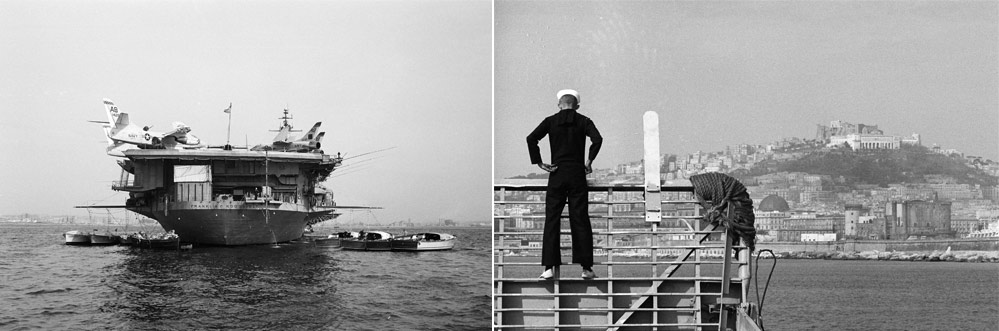

(Left) The USS Roosevelt during a press tour to Naples in 1965. (Right) The Bay of Naples in all its beauty can be seen in the background.

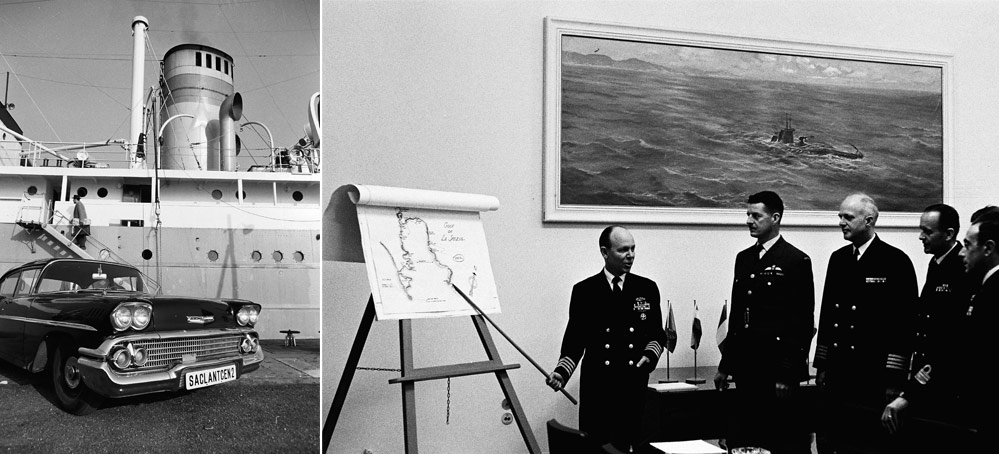

(Left) Boarding one of NATO’s oceanographic vessels in La Spezia. (Right) Going through the day’s priorities at the Centre.

The emblem of AFSOUTH - Headquarters Allied Forces Southern Europe - is the Lion of St. Mark. It is the traditional symbol of the Republic of Venice, whose patron saint is St. Mark. At the inauguration ceremony of the AFSOUTH flag in 1951, the Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces Southern Europe, Admiral Robert B. Carney, explained the chosen symbol: “The emblem on the flag represents an ancient symbol revered throughout the Mediterranean: St. Mark’s lion, symbol of power, holding open the book of peace. But the lion is also holding a raised sword as an indication of its intention to keep the peace.”

The emblem of AFSOUTH - Headquarters Allied Forces Southern Europe - is the Lion of St. Mark. It is the traditional symbol of the Republic of Venice, whose patron saint is St. Mark. At the inauguration ceremony of the AFSOUTH flag in 1951, the Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces Southern Europe, Admiral Robert B. Carney, explained the chosen symbol: “The emblem on the flag represents an ancient symbol revered throughout the Mediterranean: St. Mark’s lion, symbol of power, holding open the book of peace. But the lion is also holding a raised sword as an indication of its intention to keep the peace.”