Origins

My country and NATO

Portugal and its NATO Allies in 1949

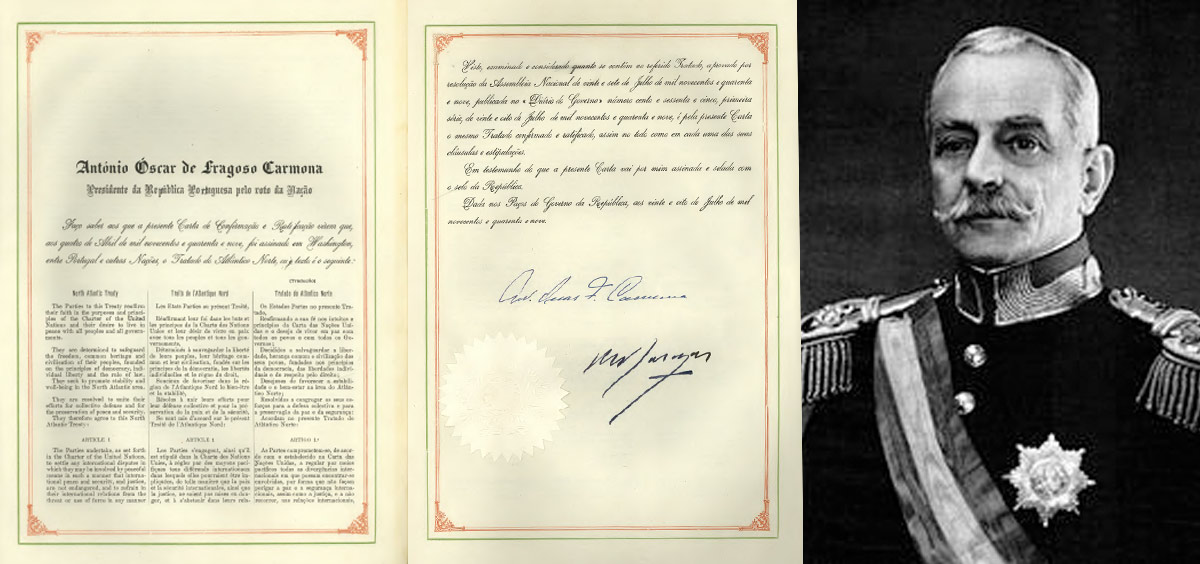

President Óscar Carmona signs the Instrument of Accession for Portugal in Lisbon on 28 July 1949

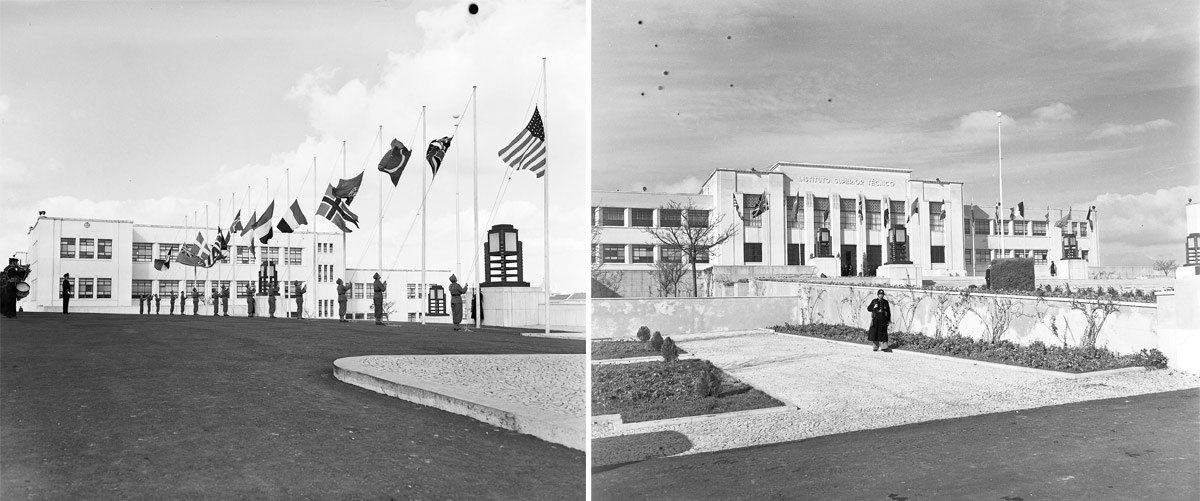

The NATO meeting in Lisbon was held at the Instituto Superior Técnico

The NATO mobile exhibition was set up in Praça da Figueira, a central square in Lisbon.

It attracted crowds of curious people.

The exhibition stayed there for several weeks, allowing members of the public to learn and ask questions about the Alliance’s principal functions.

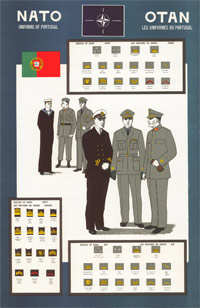

At the time, posters and publications were used to explain NATO to the public.

NATO Secretary General, Lord Ismay (left) arrives in Lisbon to visit the exhibition, together with members of the then NATO Information Committee.

Lord Ismay gave several press conferences and received front page attention from major media outlets.

In 1971, the Iberian Atlantic area command (or IBERLANT Command) moved to permanent headquarters in Oeiras, near the historic site of Forte São Julião da Barra, an eighteenth century fortification, which can be seen here on the horizon the day of the inauguration ceremony.

IBERLANT Command was the first ever international command installed on Portuguese soil.

The site was heavily secured...

...and the toing and froing on and off the site well controlled.

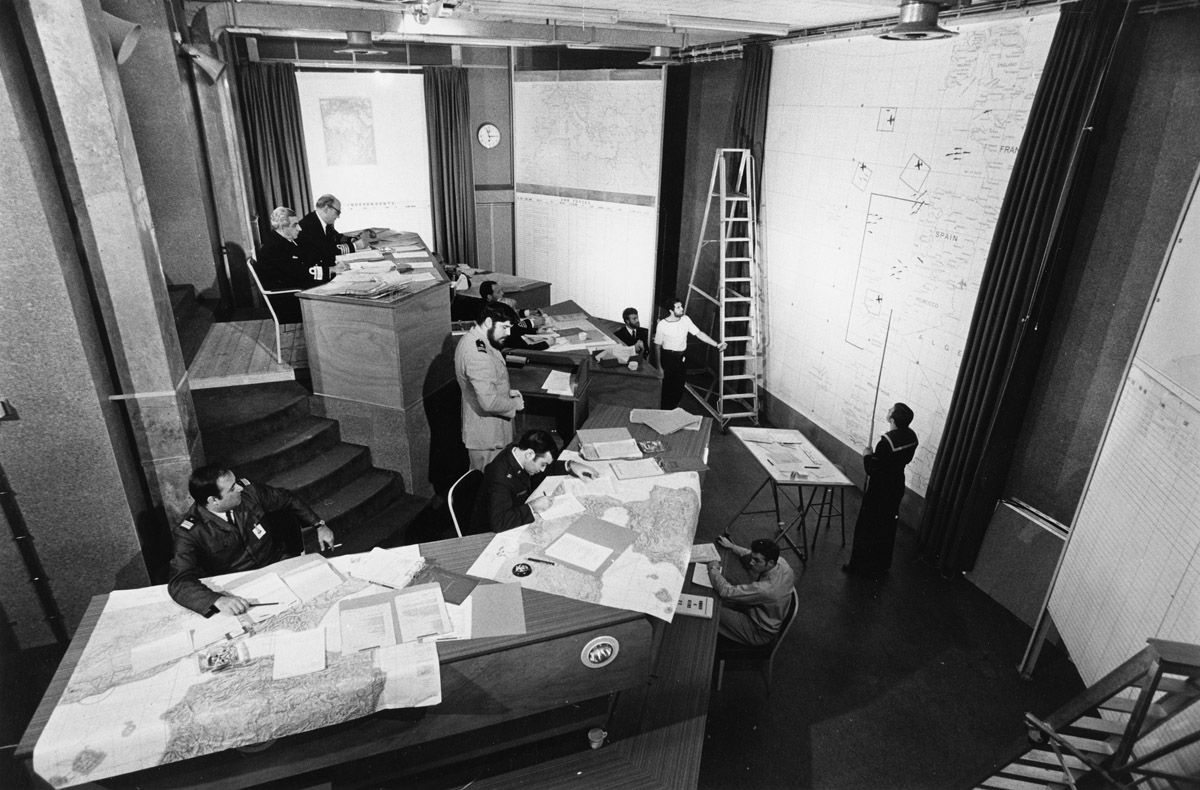

The Command consisted of an above-ground administrative block...

...and an underground operational command post.

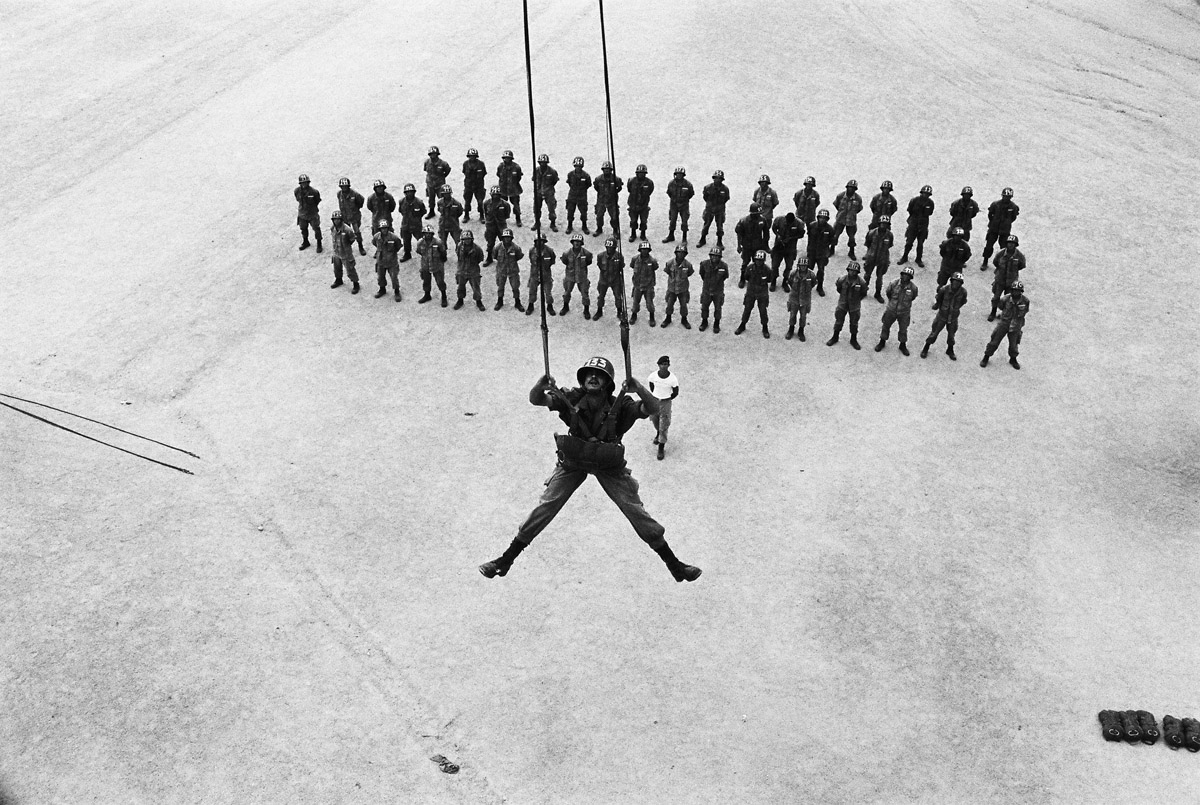

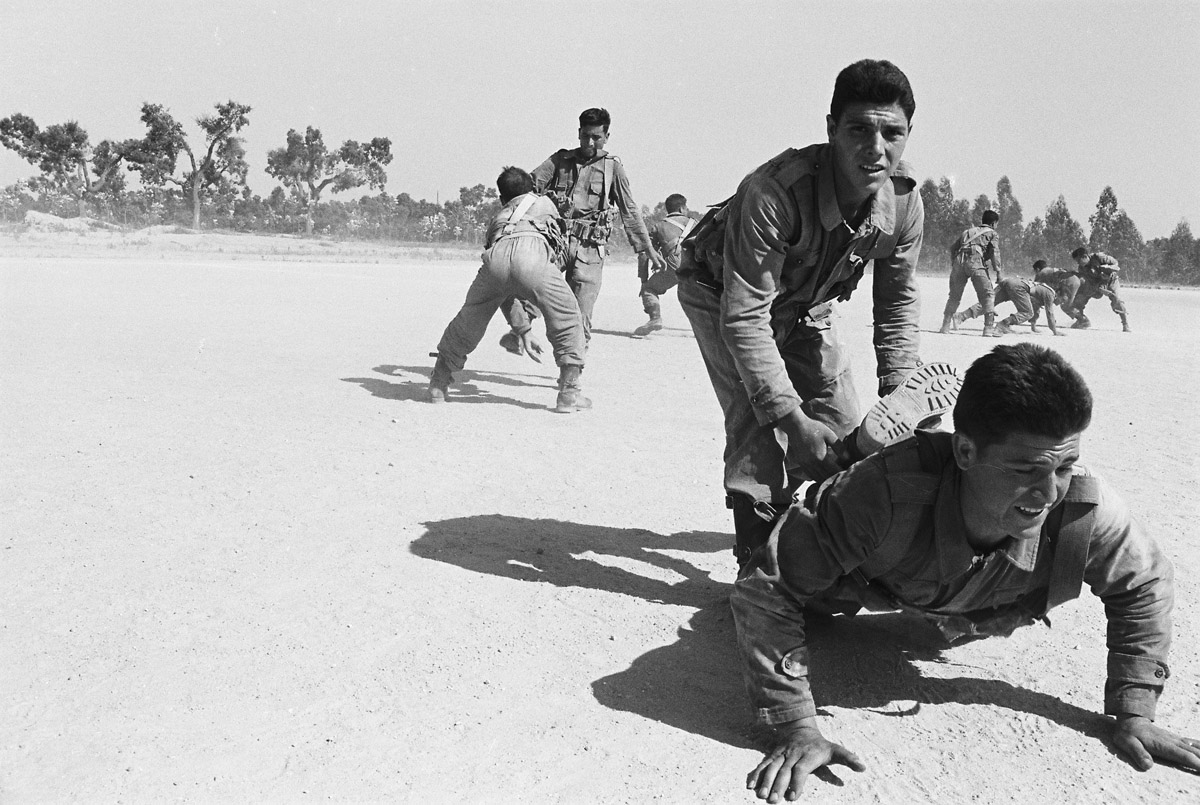

In times of peace, it was responsible for surveillance, preparing defence plans and conducting joint training exercises.

A Portuguese delegation arrives at NATO headquarters in Brussels, Belgium.

Portuguese Defence Minister (1968 - 1971), General Sa de Viana Rebelo, attends a NATO meeting in 1971.

(Right) Portuguese Prime-Minister (1975-1976) José Pinheiro de Azevedo at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, Belgium.

(Middle) Mario Soares, Portuguese Prime Minister (1983 - 1985) at the June 1974 meeting in Ottawa.

NATO Secretary General, Joseph Luns (right) greets President Ramalho Eanes (left) as he arrives at NATO Headquarters on 30 April 1982.

President Ramalho Eanes (left) addresses the Council on 30 April 1982 as NATO Secretary General, Joseph Luns (right) looks on.

(Right) Defence Minister (1985 – 1991), Jaime Gama participating in discussions at NATO.

(Right) Cavaco Silva, Prime-Minister (1985 – 1995) and (left) Joao de Deus Pinheiro, Minister of Foreign Affairs (1987 – 1992) attend the 1989 NATO Summit in Brussels.

The ninth session of the North Atlantic Council in Lisbon, 20 to 25 February 1952, was where NATO reorganised its civilian structure: the North Atlantic Council became a permanent body, comprised of permanent representatives from each of its member countries; Allies decided to appoint a Secretary General to lead a newly created International Secretariat designed to assist the Council in carrying out its increasing responsibilities; Allies also decided to move NATO headquarters from Belgrave Square in London, United Kingdom, to France to be closer to NATO’s military headquarters in Versailles; and Greece and Turkey attended the meeting as fully-fledged NATO members, marking de facto what constituted NATO’s first wave of enlargement. On the occasion of this meeting, Portugal issued the first ever NATO commemorative stamp.

The ninth session of the North Atlantic Council in Lisbon, 20 to 25 February 1952, was where NATO reorganised its civilian structure: the North Atlantic Council became a permanent body, comprised of permanent representatives from each of its member countries; Allies decided to appoint a Secretary General to lead a newly created International Secretariat designed to assist the Council in carrying out its increasing responsibilities; Allies also decided to move NATO headquarters from Belgrave Square in London, United Kingdom, to France to be closer to NATO’s military headquarters in Versailles; and Greece and Turkey attended the meeting as fully-fledged NATO members, marking de facto what constituted NATO’s first wave of enlargement. On the occasion of this meeting, Portugal issued the first ever NATO commemorative stamp.

As a token of its lasting commitment to the Alliance, in July 1989, the Portuguese Government offered NATO a scale model of a XVI century

As a token of its lasting commitment to the Alliance, in July 1989, the Portuguese Government offered NATO a scale model of a XVI century