Origins

My country and NATO

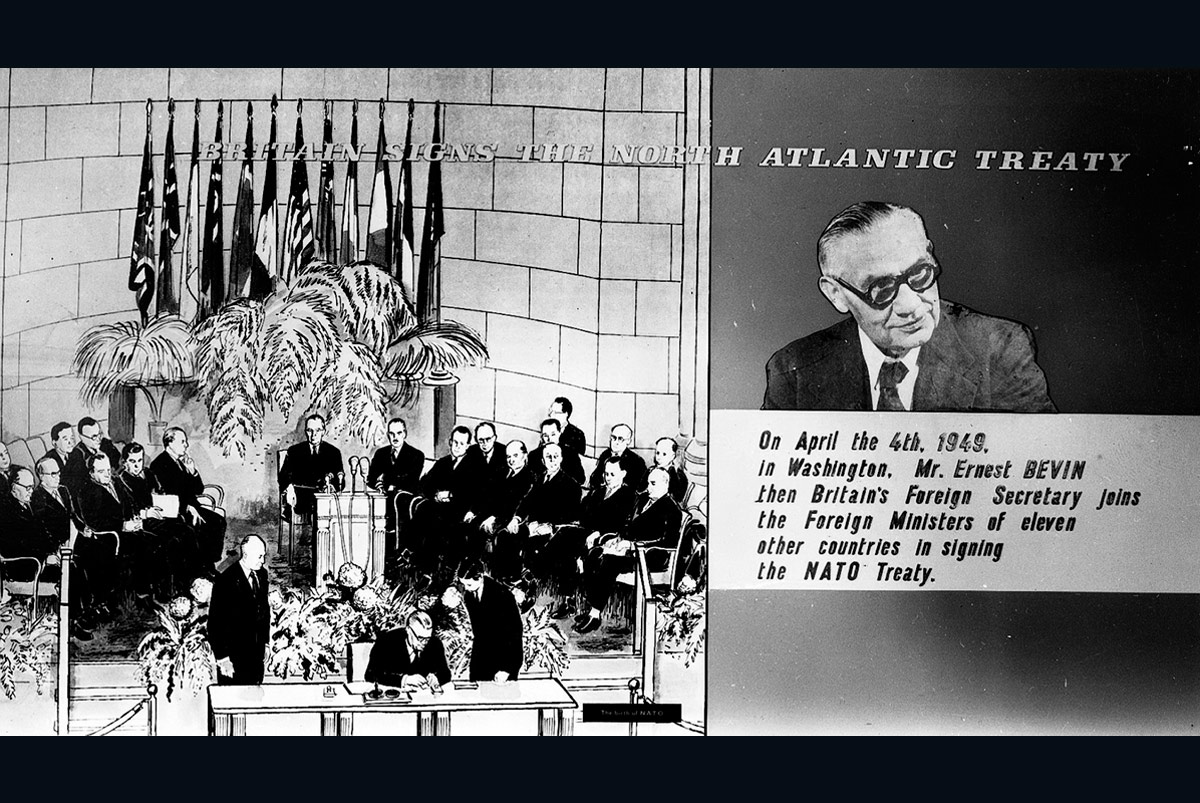

The United Kingdom and its NATO Allies In 1949

The Instrument of Accession signed by His Majesty King George VI in London on 17 May 1949.

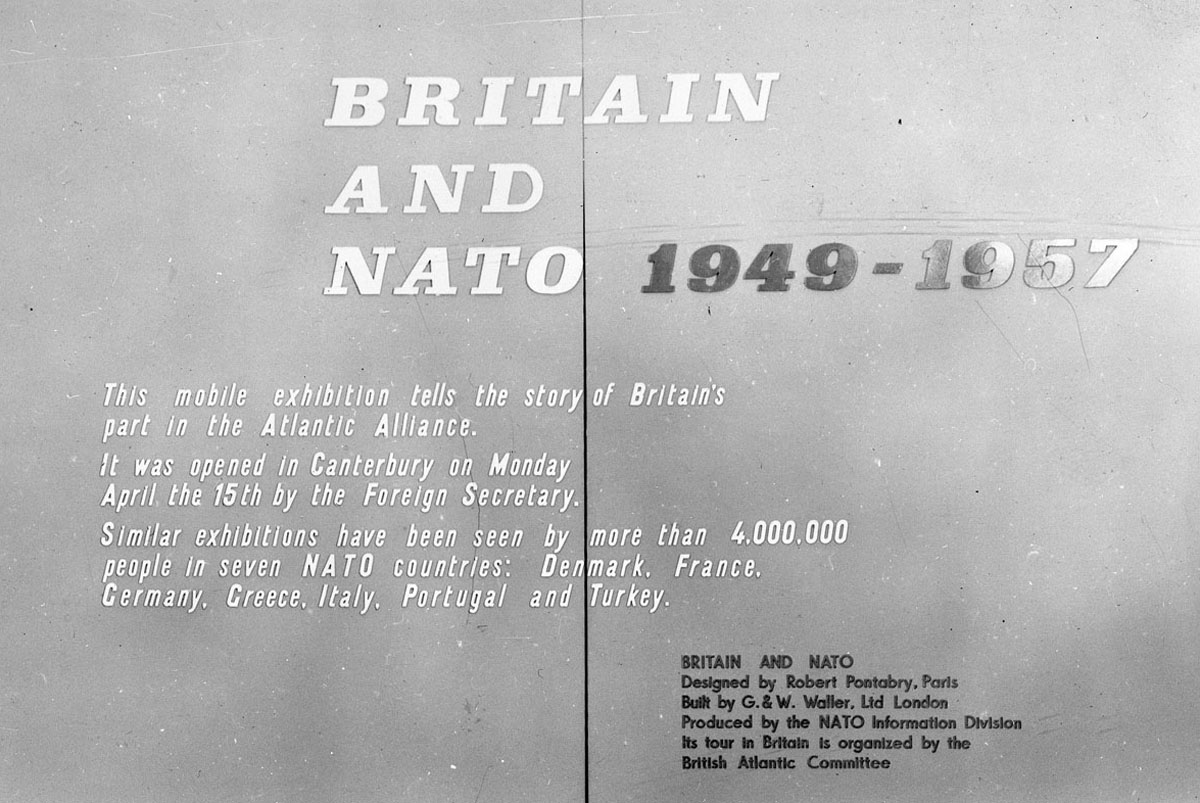

Opening ceremony of the NATO exhibition in the City of Canterbury.

The NATO exhibit crossed the Channel in 1957.

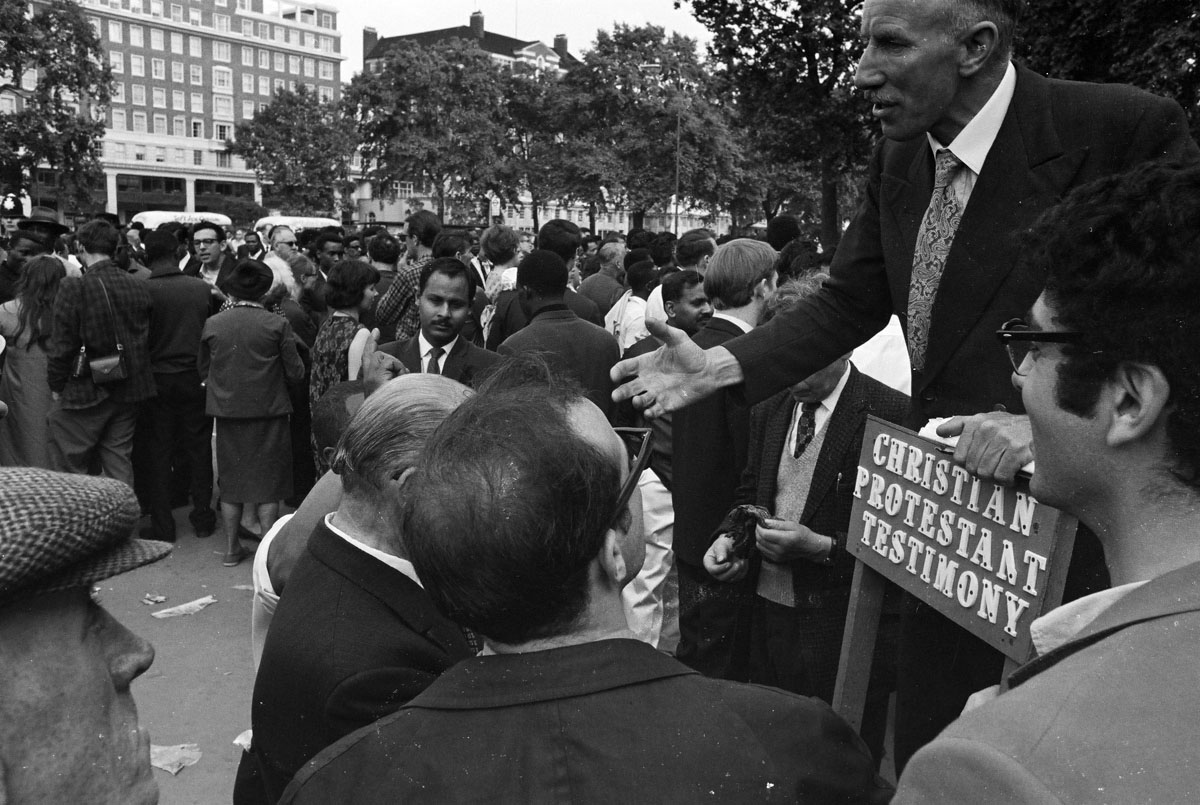

NATO's mobile exhibitions had been touring member countries since 1952.

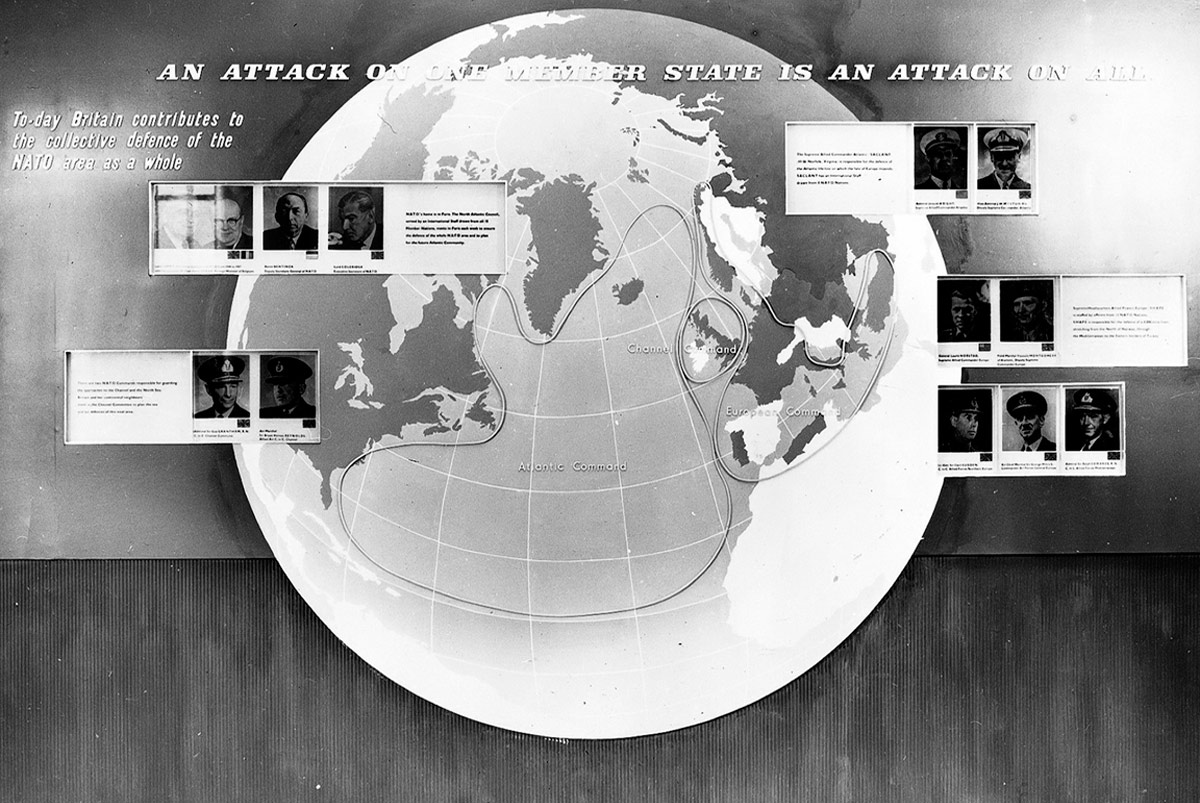

Panels explained key facts and principles on the Alliance. Here, the idea of collective defence is put to the fore.

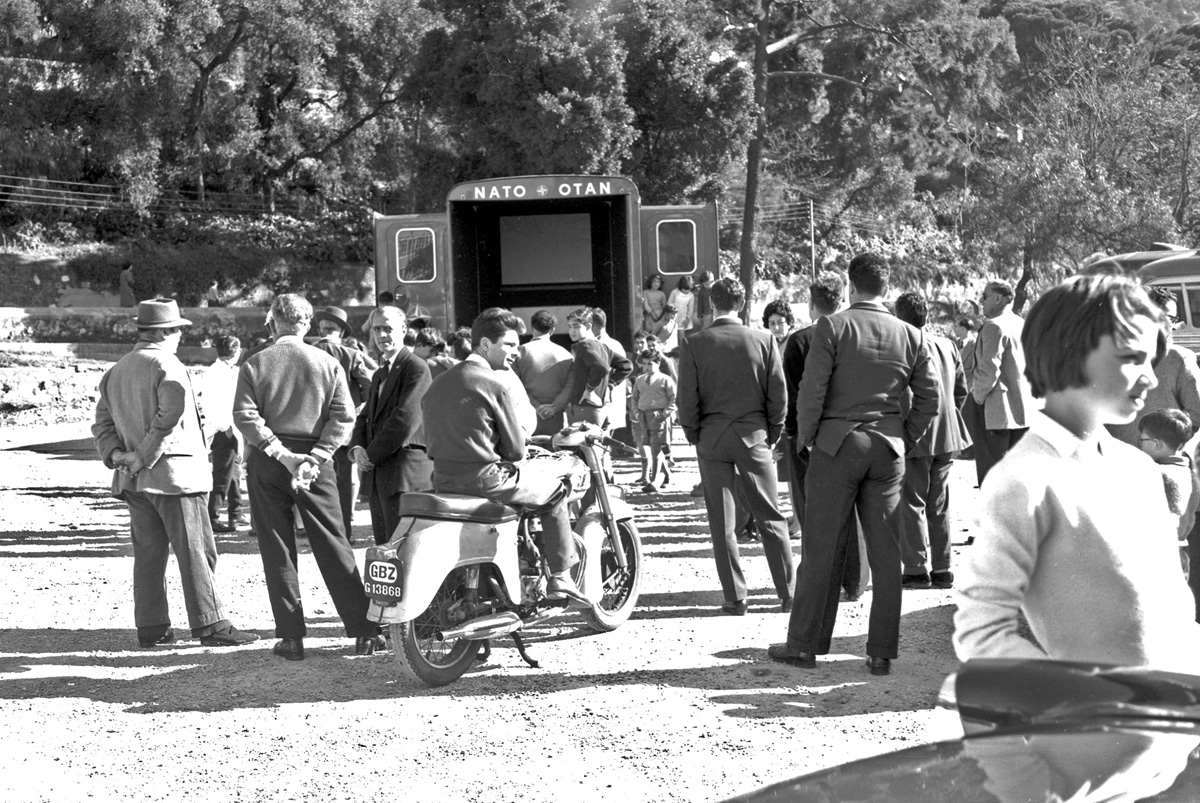

The mobile exhibition also travelled to Gibraltar in the 1950s.

Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II at a meeting of NATO ministers in London, 1965.

Celebrities of another kind were also caught on camera as they visited NATO. Here, Audrey Hepburn is at SHAPE in Mons, Belgium in 1965 during the filming of her movie “How to steal a million dollars.”

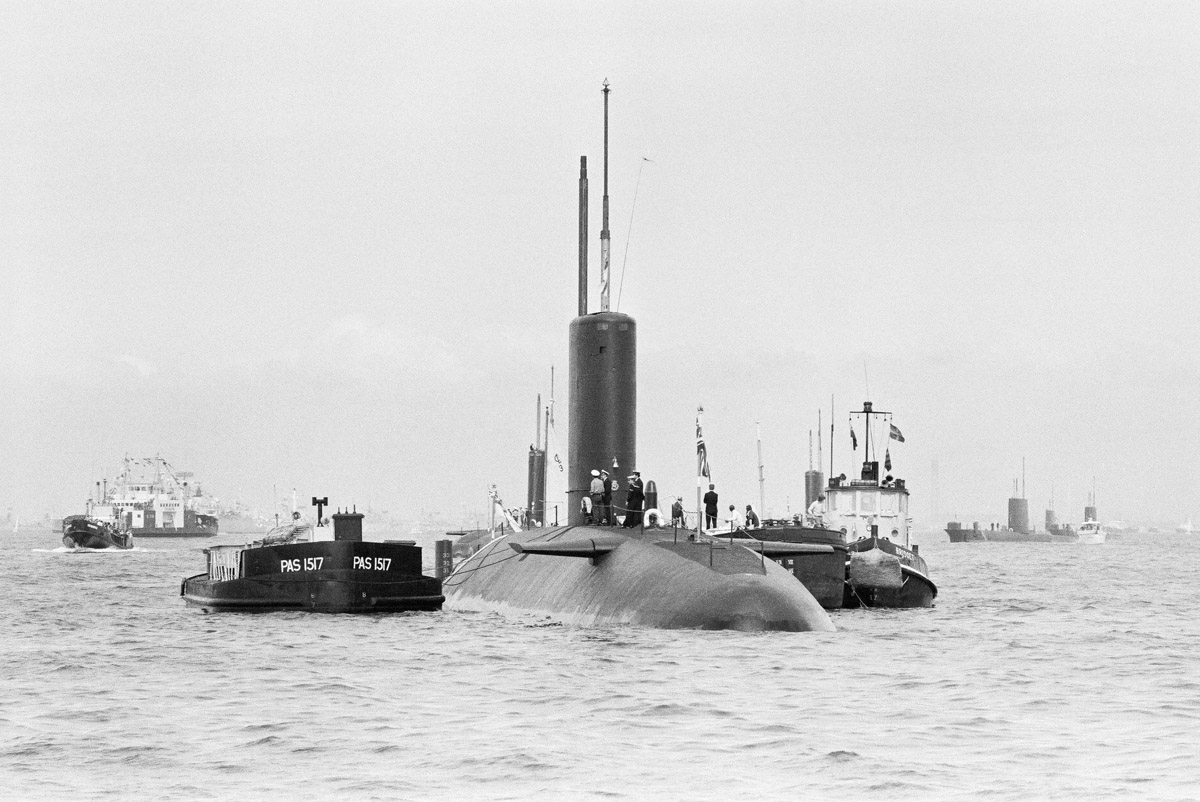

Preparations are ongoing before the arrival of HM Queen Elizabeth II on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of NATO Navies being celebrated in Stiphead, near Portsmouth, United Kingdom.

On 25 November 1980, Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II attends a meeting of the North Atlantic Council with the NATO motto clearly visible to all: “Animus In Consulendo Liber”.

Before deliberations start, the British Ambassador to NATO Sir Clive Rose speaks to HM Queen Elizabeth II.

After the discussions, HM Queen Elizabeth II meets NATO staff, who keenly await to catch a glimpse of her.

Prince Charles in discussion with NATO Secretary General Joseph Luns during his visit to NATO Headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, 11 March 1987.

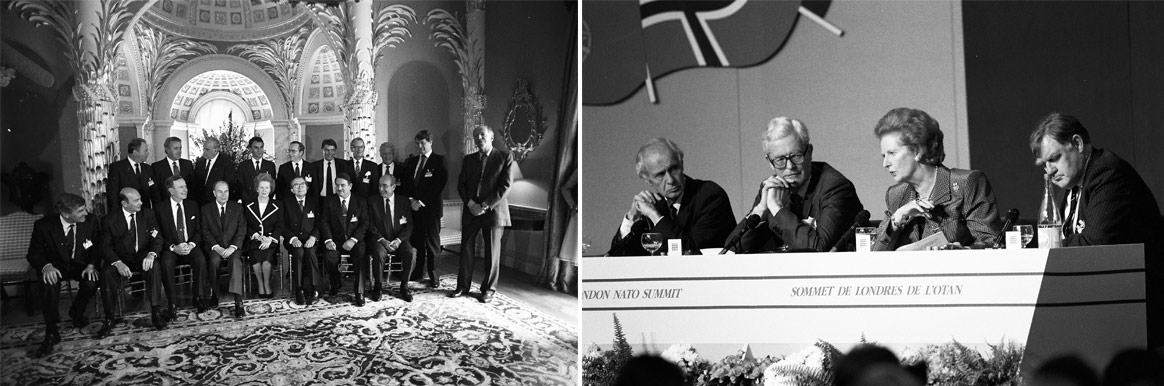

A close-up of the family portrait of HM Queen Elizabeth II with NATO Heads of State and government at the London Summit in 1990. At this historical event, NATO offered a “hand of friendship” to its former adversaries on the other side of the “Iron Curtain”.

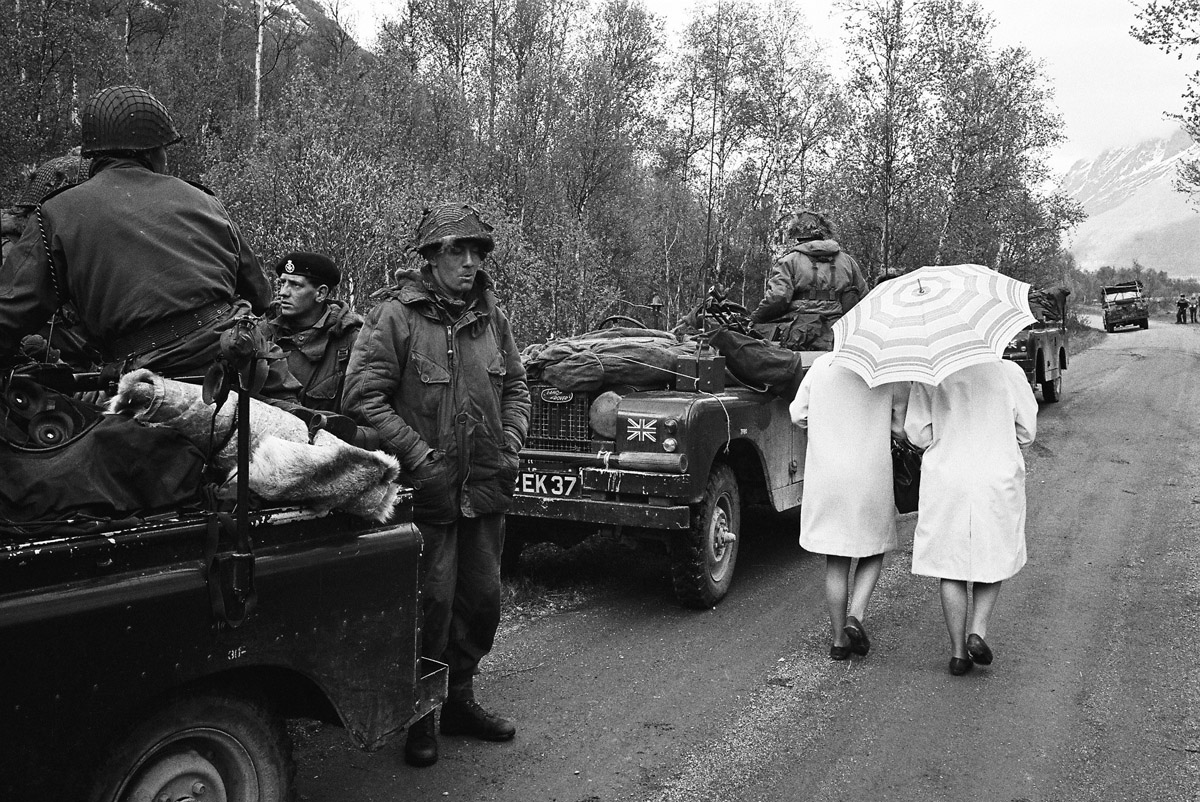

Soldiers from the British Army of the Rhine on patrol, 1944-1945

Working at Allied Command Channel (1952-1994)

Left: A family portrait of NATO leaders at Lancaster House, London, during the summit. Right: British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher with Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Douglas Hurd on her right.

The first NATO Headquarters was in London at 13, Belgrave Square. NATO remained in the British capital for two years before moving to Paris, closer to where the military headquarters were being constructed. The move was a challenge in its own right: it was the biggest furniture removal operation ever undertaken in the United Kingdom by air. Ninety tons of office equipment and furniture were flown across the Channel. Normal shipping methods were discarded as they would have interrupted day-to-day business for too long.

The first NATO Headquarters was in London at 13, Belgrave Square. NATO remained in the British capital for two years before moving to Paris, closer to where the military headquarters were being constructed. The move was a challenge in its own right: it was the biggest furniture removal operation ever undertaken in the United Kingdom by air. Ninety tons of office equipment and furniture were flown across the Channel. Normal shipping methods were discarded as they would have interrupted day-to-day business for too long.