Origins

My country and NATO

Iceland and its NATO Allies in 1949

People begin to gather in front of the Icelandic Parliament on the day it is set to vote on NATO membership, 30 March 1949. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

Hundreds of protestors—both NATO critics and supporters—rally in front of the Parliament during the vote. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

Police officers line up in front of the Althingi and try to maintain order. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

Fights break out between NATO critics and supporters. Note the building’s smashed windows. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

People flee from tear gas in Austurvöllur Square. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

Police use tear gas to try to disperse the crowd. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

Some protestors ripped off pieces of this picket fence to use as cudgels during the brawl. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

The front of the Althingi shows damage from rocks and other debris hurled by the protestors. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

The main doors of the Althingi the day after the protest, 31 March 1949. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

The parliamentarians had the windows to the chamber covered with plywood to protect them from projectiles being thrown by protestors. Despite the chaos, the parliamentarians voted by a large majority to join NATO. Photo credit: Arnaldur Grétarsson & family, Valgerður Tryggvadóttir

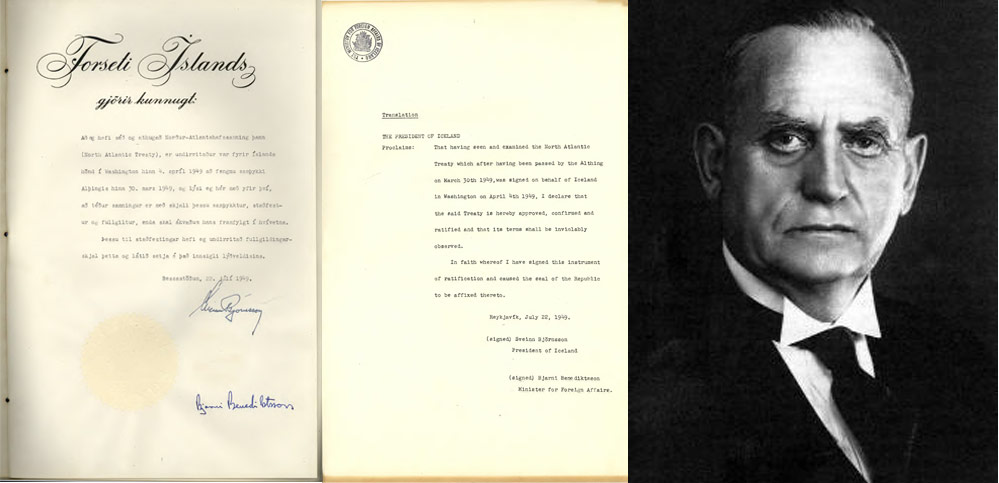

Reykjavík, 22 July 1949, President of the Republic H.E. Sveinn Björnsson signs the instrument of accession for Iceland

Keflavik Air Base sign

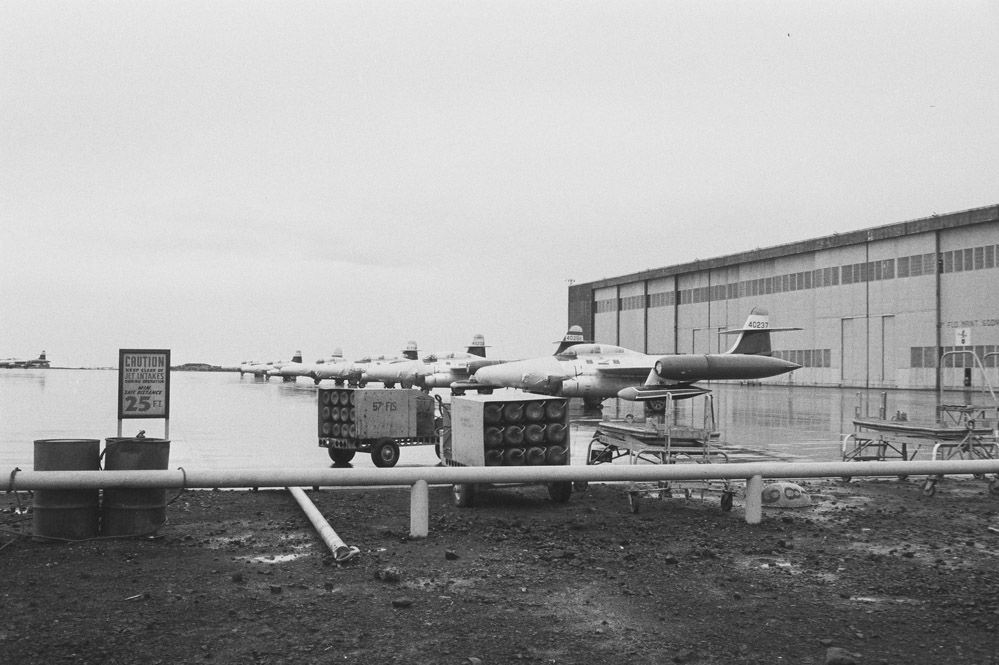

American planes at Keflavik Air Base

US Navy helicopter training in Iceland

Keflavik in winter

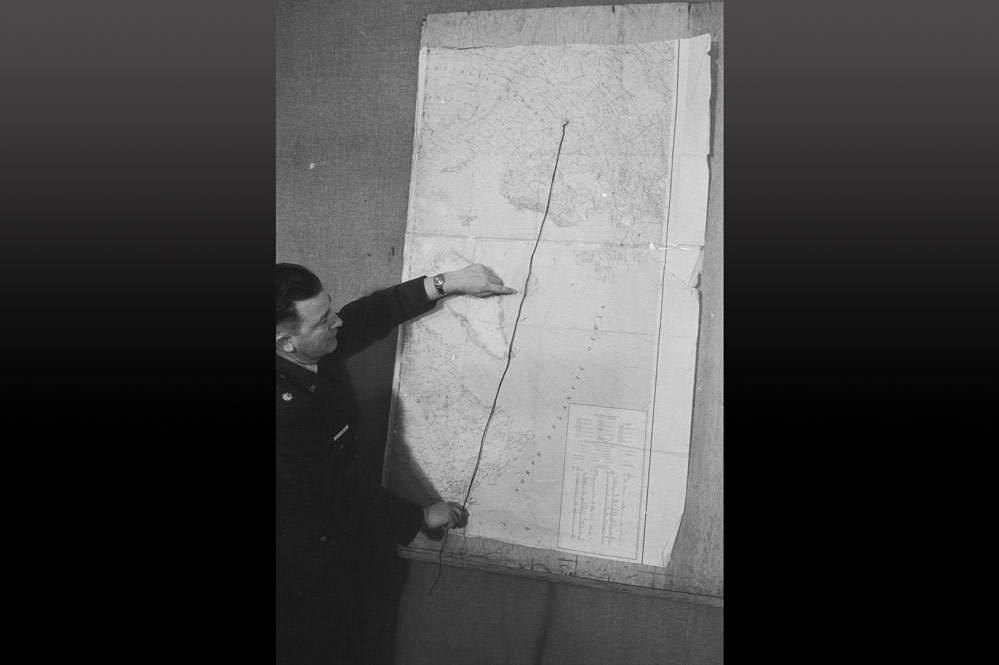

American officer points at Iceland’s place on air route between Moscow and Washington, D.C.

Sign for airfield at Keflavik shows distances to major world cities

Bus at entrance of Keflavik base

American planes stationed at Keflavik

US Air Force surveillance plane

Dutch officer participating in NATO air surveillance alongside US forces

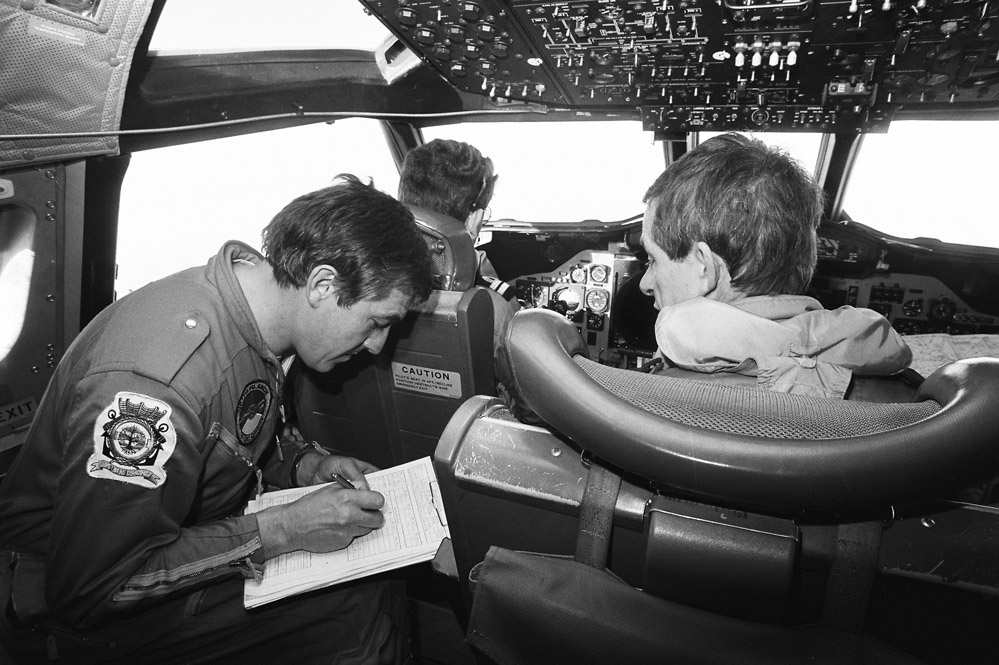

Air surveillance from inside plane

Aerial photo of Keflavik Air Base taken on 19 August 1982 by US Air Force

Icelandic Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson welcomes delegates to 1968 NATO ministerial meeting in Reykjavik.

Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson delivers speech with West German Chancellor Willy Brandt (left) and NATO Secretary General Manlio Brosio (right).

Bjarni sits between Brandt and Brosio.

NATO Secretary General Manlio Brosio delivers speech as West German Chancellor Willy Brandt (left) and Icelandic Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson (centre) look on.

Delegates arrive at the 1968 NATO ministerial meeting in Reykjavik aboard an Icelandair plane.

A post office in Reykjavik during the 1968 NATO ministerial meeting.

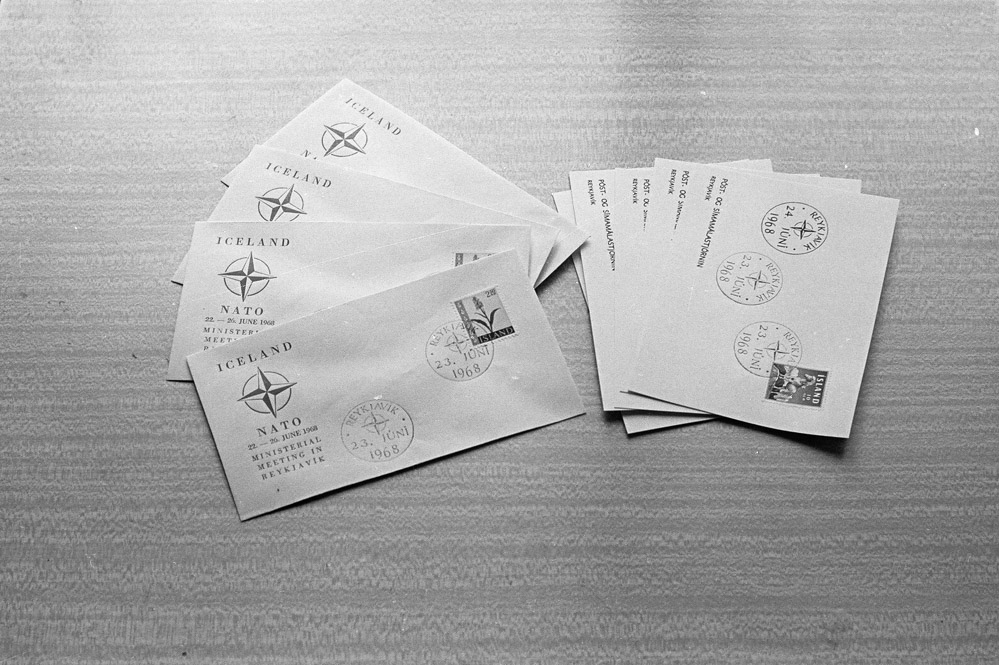

Mail showing special stamps produced for the 1968 NATO ministerial meeting in Reykjavik.

Flags of all 15 NATO member states fly in central Reykjavik during the 1968 meeting of NATO foreign ministers.

Anti-NATO protestors gather outside NATO ministerial meeting in Reykjavik carrying signs demanding “Ísland úr NATO.”

Anti-NATO protestors manifest for many different causes, including criticisms of the Vietnam War, the Greek military junta, and the American military presence in Iceland.

In 1963, Iceland donated a hand-carved gavel to NATO, to be used by the Secretary General during meetings of the North Atlantic Council. The gavel was carved from palisander wood by renowned Icelandic sculptor Ásmundur Sveinsson. The twin of this gavel was presented by Iceland to the United Nations General Assembly, the only difference being the NATO compass symbol carved into the NATO gavel’s handle. Unfortunately, Secretary General Joseph Luns reported in 1975 that the NATO gavel had been damaged, so Iceland presented NATO with a replica of the original gift.

In 1963, Iceland donated a hand-carved gavel to NATO, to be used by the Secretary General during meetings of the North Atlantic Council. The gavel was carved from palisander wood by renowned Icelandic sculptor Ásmundur Sveinsson. The twin of this gavel was presented by Iceland to the United Nations General Assembly, the only difference being the NATO compass symbol carved into the NATO gavel’s handle. Unfortunately, Secretary General Joseph Luns reported in 1975 that the NATO gavel had been damaged, so Iceland presented NATO with a replica of the original gift.