Origins

My country and NATO

Canada and its NATO Allies in 1949

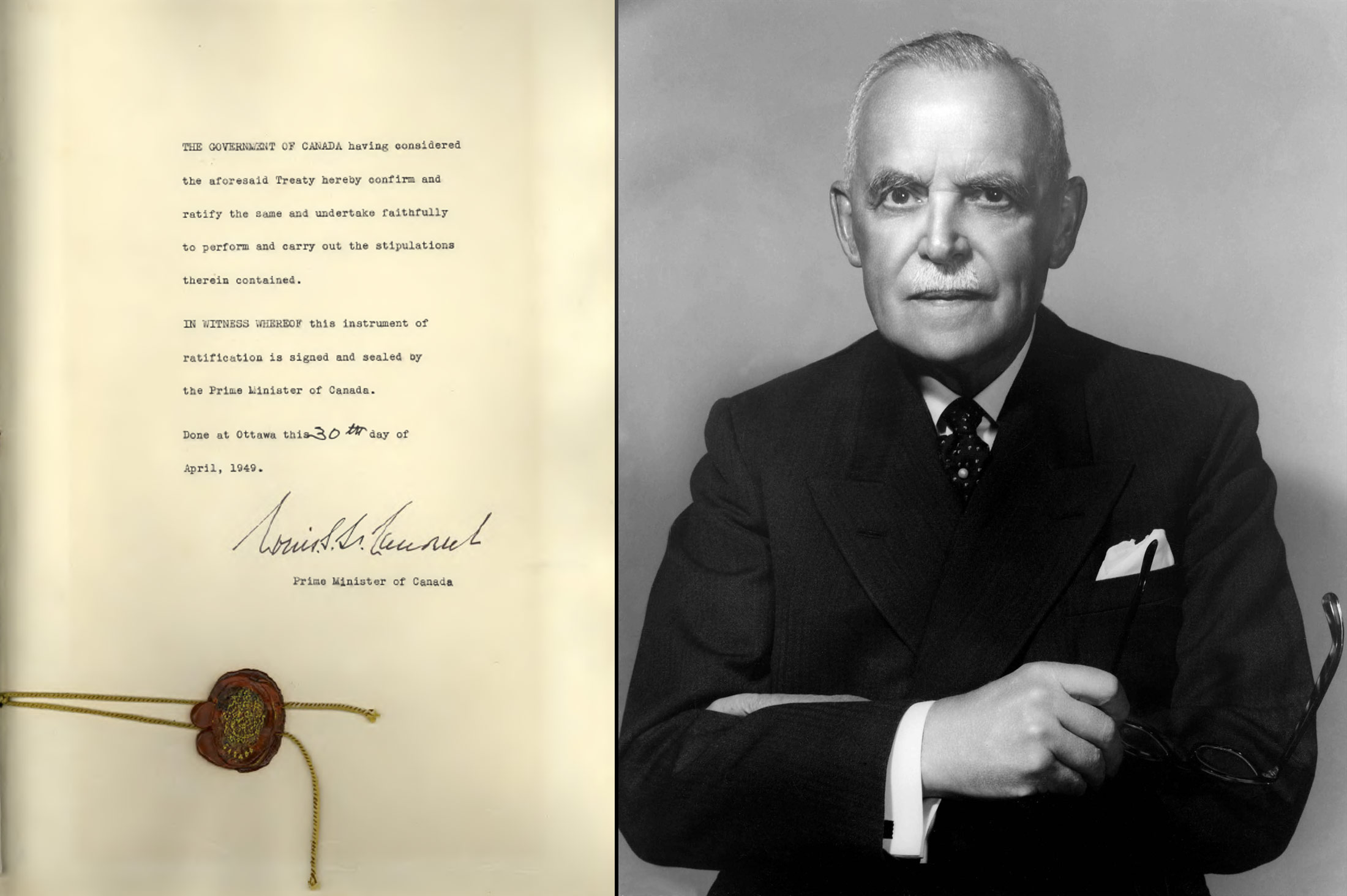

Canada’s Instrument of Accession to NATO was signed in Ottawa by Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, 30 April 1949, formally confirming Canada’s entry into NATO.

The Three Wise Men. From left to right: Halvard Lange of Norway, Gaetano Martino of Italy, and Lester B. Pearson of Canada.

Pearson at Germany’s accession to NATO, 1955

Delegates meet in the Canadian House of Commons at the 1951 NATO ministerial meeting in Ottawa, when Allies agreed to welcome Greece and Turkey into the Alliance.

Canadian Armed Forces service members hold the flags of NATO member countries outside the Parliament of Canada at the 1963 NATO ministerial meeting in Ottawa.

Armed forces personnel raise the flags of all 15 NATO Allies to open the 1963 ministerial meeting.

The 1963 NATO ministerial meeting in the House of Commons chamber.

Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson greets delegates to the 1963 ministerial meeting.

Opposition Leader (and former Prime Minister) John Diefenbaker in the House of Commons during the 1963 NATO ministerial meeting. Barely a month earlier, his government had been defeated in the House, losing a vote of non-confidence on the stationing of American nuclear missiles on Canadian soil. Diefenbaker was opposed whereas Pearson was in favour.

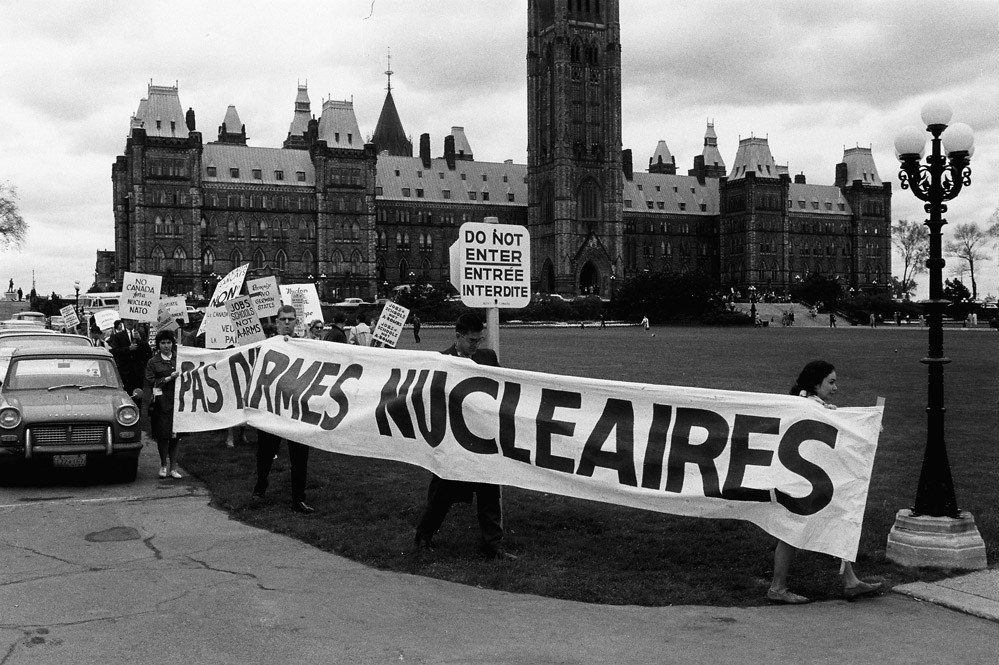

Protestors outside Parliament at 1963 ministerial meeting.

Protestors outside Parliament at 1963 ministerial meeting.

CBC News van sits outside Parliament building during the 1963 ministerial meeting.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer stands beside bilingual stop sign on Parliament Grounds at the 1963 ministerial meeting.

Welcoming delegates to the 1974 ministerial meeting on Parliament Hill.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers stand guard outside Parliament during the 1974 NATO ministerial meeting.

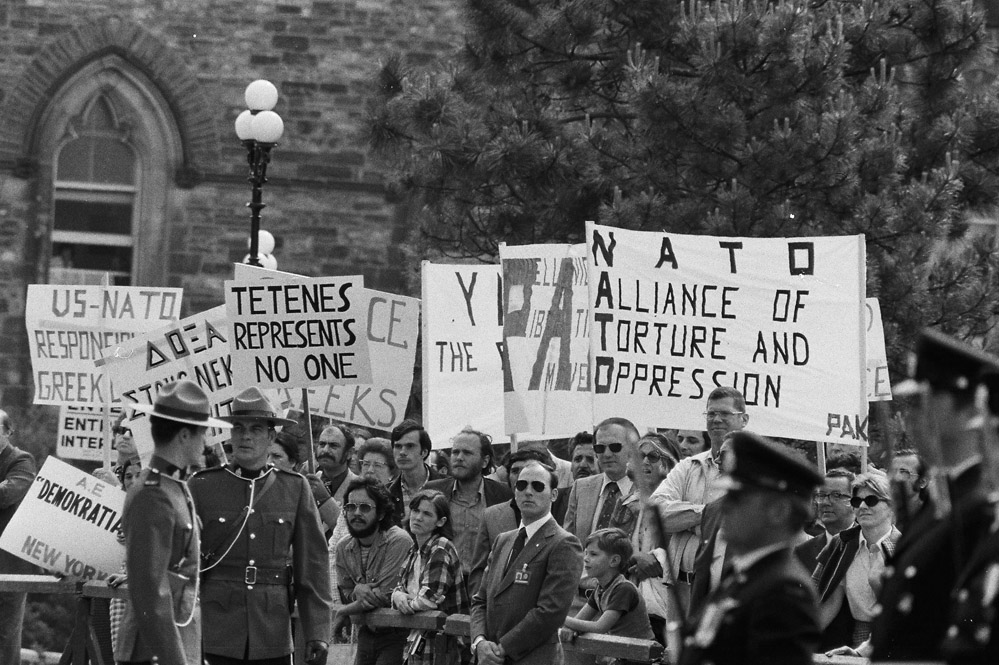

Mounties look on as protestors picket 1974 ministerial meeting.

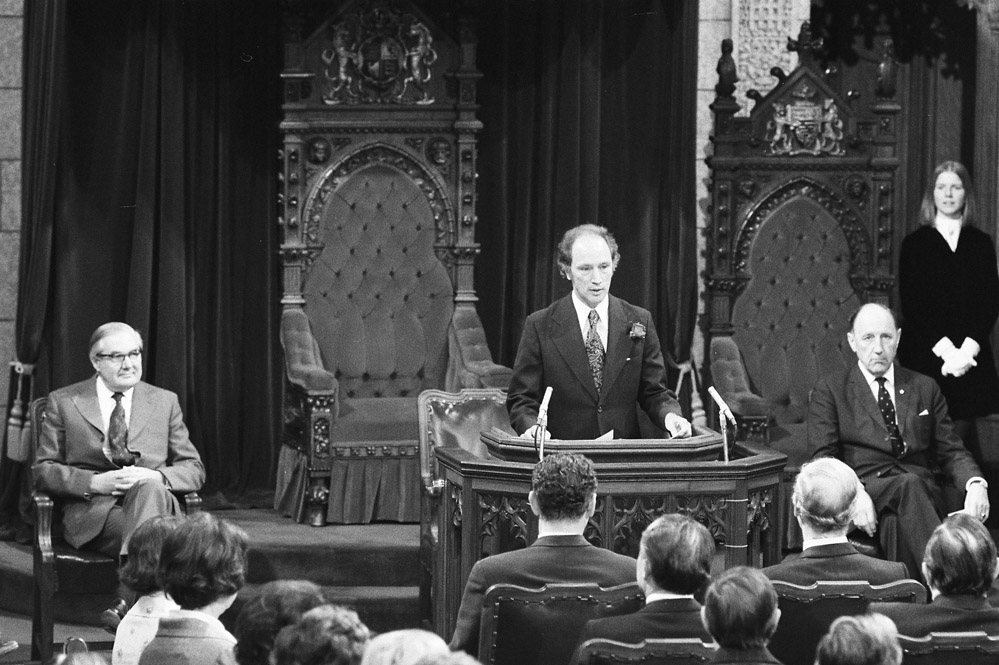

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau addresses NATO ministers and other delegates in the Canadian Senate Chamber, June 1974.

Prime Minister Trudeau speaking in the Senate Chamber. To his left is NATO Secretary General Joseph Luns.

A Mountie guards UK Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe and US Secretary of State George P. Schulz at the NATO ministerial meeting in Halifax, May 1986.

NATO Open Skies conference in Ottawa, February 1990. On the margins of this meeting between NATO and Warsaw Pact countries, the Western Allies and the USSR began the Two Plus Four framework that eventually unified Germany in October 1990.

Canadastrasse (German for "Canada Street") on a NATO military base in West Germany during the Cold War.

Military children play in playground on Canadian military base in West Germany.

Canadians shopping at the grocery store at SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe) in France.

Mother and daughter from a Canadian military family stationed in Europe.

Father with two boys at the SHAPE school in Rocquencourt, France.

Playing volleyball in the woods.

Baseball game organised for Canadian armed forces personnel.

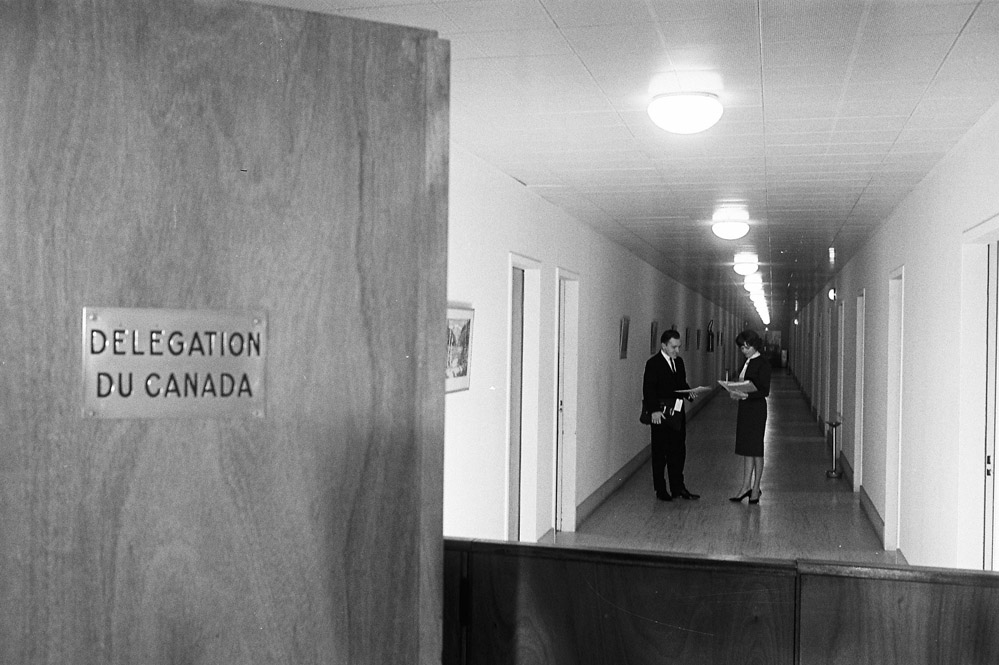

Canadian Delegation at NATO Headquarters in Paris, December 1963.

Canada's ambassador to NATO, George Ignatieff, holds a staff meeting in the Canadian delegation.

Mrs. Jessie Ignatieff shows off Canadian artwork in the delegation

Canadian students attend a NATO youth conference at NATO Headquarters in Paris, 1956.

Canadian military band plays in the press theatre at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, October 1984.

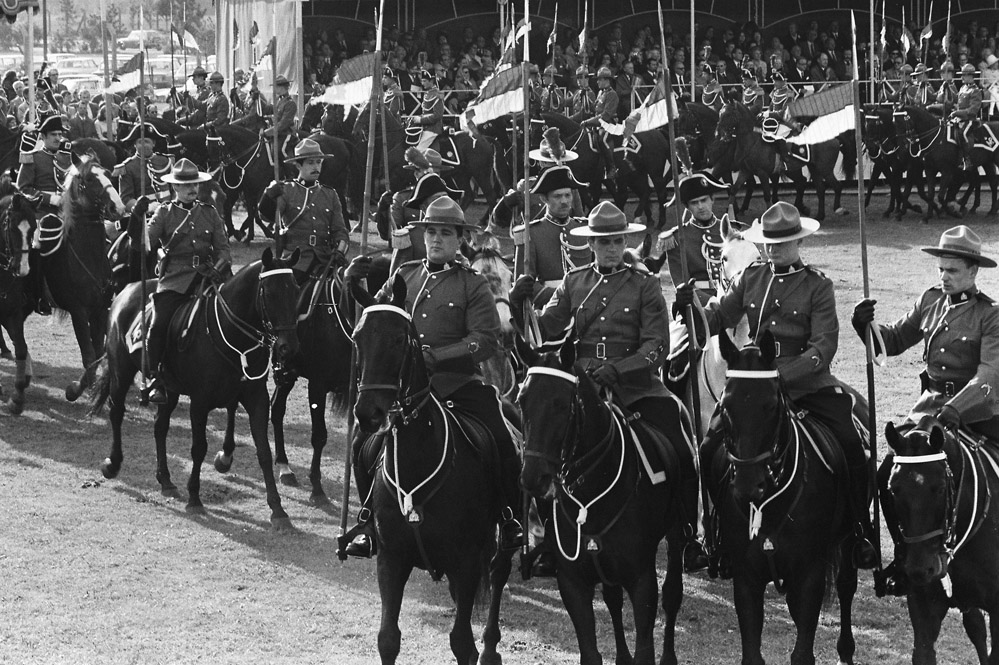

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Musical Ride at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, Belgium in 1974.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Musical Ride at NATO HQ, 1974

Royal Canadian Air Force Base - Grostenquin, France, 1954

Royal Canadian Air Force Base - Grostenquin, France, 1954

Royal Canadian Air Force Base - Grostenquin, France, 1954

Royal Canadian Air Force pilots and F-104 starfighters, supersonic interceptor aircraft at Royal Canadian Air Force Base Zweibrucken, West Germany, 1963

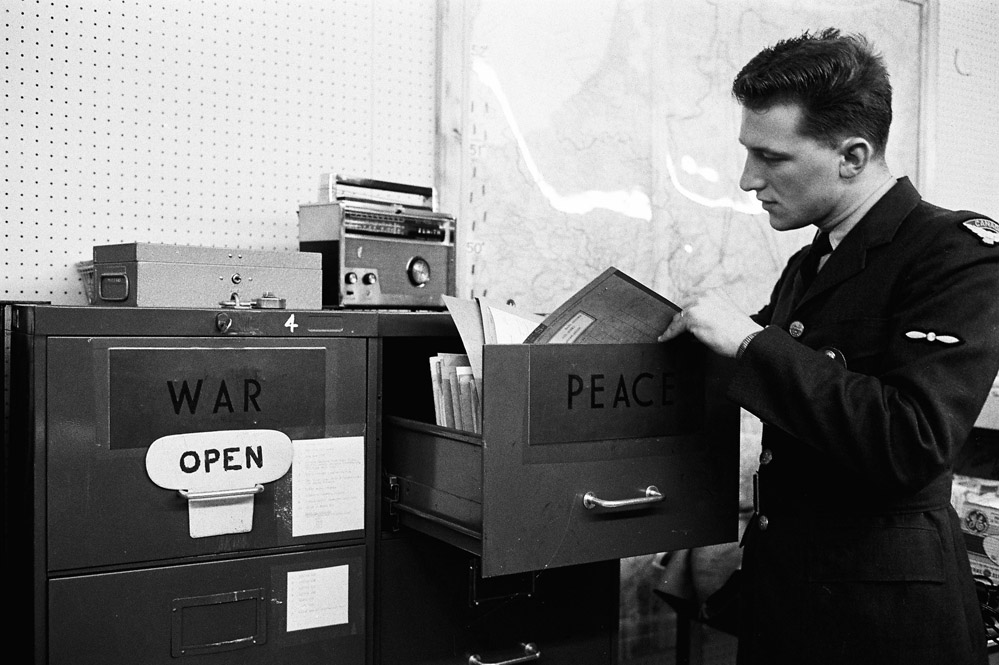

Canadian soldier consulting documents at Royal Canadian Air Force Base Zweibrücken, West Germany, 1963

Soldiers off duty exploring the town of Metz, France, 1963

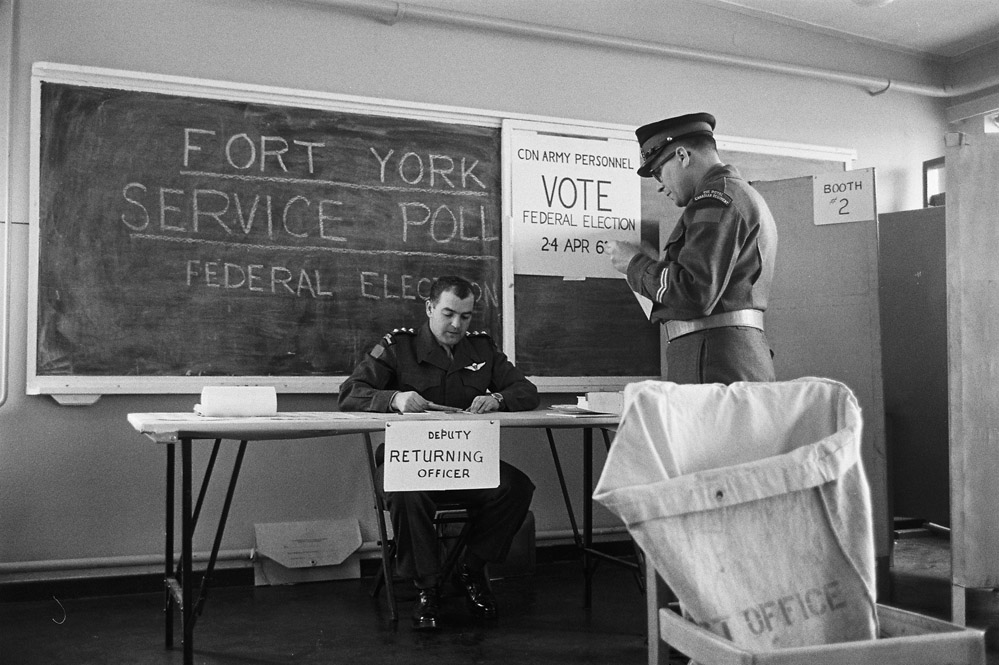

Soldiers voting on-base in the 1963 Canadian federal election. Zweibrücken, West Germany, 1963

Canadian soldier aiming during exercise in Soest, West Germany, 1963

Canadian armed forces parade during exercise in Soest, West Germany, 1963

Canadian soldiers pose with sign during NATO Exercise Winter Express in Norway, 1966

Canadian soldiers arrive in Denmark for NATO Exercise Green Express, 1969

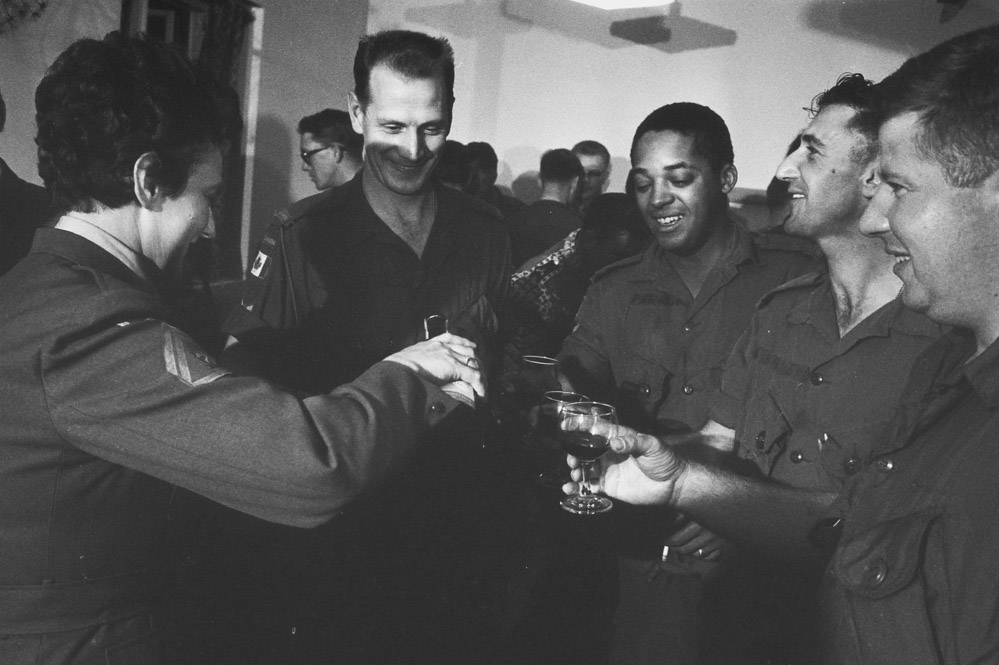

Canadians fraternise with Danish and Americans during NATO Exercise Green Express in Denmark, 1969

Danish boys play on Canadian armoured vehicle during NATO Green Express exercise in Denmark, 1969

Canadian soldier on surveillance mission during Exercise Green Express in Denmark, 1969.

Preparing for lift-off at Lahr, West Germany base, 1969

Royal Canadian Air Force pilots and F-104 starfighters, supersonic interceptor aircraft at Lahr, West Germany base, 1969

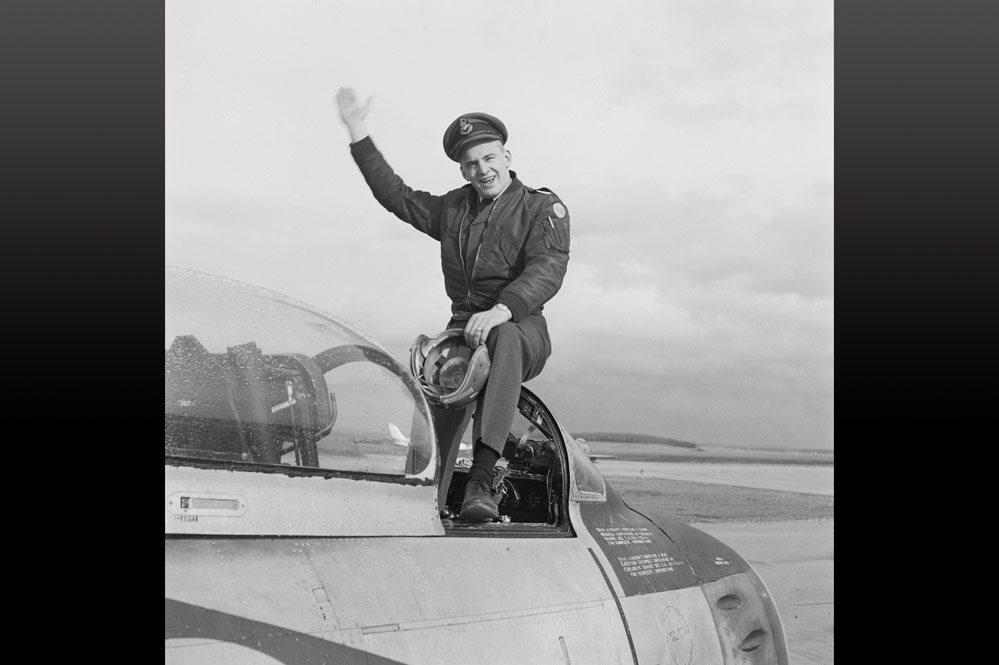

Close-up of Royal Canadian Air Force pilot at Lahr, West Germany base, 1969

Canadian tank among German Volkswagen Beetles during NATO Exercise Tomahawk in Soest, West Germany, 1969

Mechanic services F.100 fighter jet at Royal Canadian Air Force Base in Baden-Soellingen, West Germany

Canada hosted the Canadian Army Trophy tank competition in West Germany from 1963-1991. Here, tanks parade at the 1977 competition.

Canada won the Canadian Army Trophy itself—a silver replica of a Centurion tank—in 1977

In 1981, the Canadian team did not fare as well

Canadian tanks lined up at 1985 competition

Soldiers load tank at 1985 competition

Competitors find some time to toss around a football on the side lines of the 1985 Canadian Army Trophy contest

Canadian Defence Minister, Kim Campbell, was the first female defence minister in the Alliance. Here, attending the NATO Defence Ministers’ meeting in 1993. Immediately after this appointment, she became Canada’s first ever female Prime Minister.

Canadian Defence Minister, Kim Campbell, was the first female defence minister in the Alliance. Here, attending the NATO Defence Ministers’ meeting in 1993. Immediately after this appointment, she became Canada’s first ever female Prime Minister. The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) is a binational command run by Canada and the United States, which monitors the Arctic skies for incoming threats. It is not part of NATO, but is a joint contribution to Allied security. Throughout the Cold War, and continuing today, Canada’s North has hosted NORAD radar stations.

The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) is a binational command run by Canada and the United States, which monitors the Arctic skies for incoming threats. It is not part of NATO, but is a joint contribution to Allied security. Throughout the Cold War, and continuing today, Canada’s North has hosted NORAD radar stations.