His arrival was met with protests and street riots in Paris and other French cities, organised by the French Communist Party. They marched with signs declaring him “Ridgway Assassin” and “Ridgway the American monster.” People also protested in London, with an even simpler message: “Ridgway Go Home.” The slogan was painted on walls in France, the United Kingdom, and Italy. Hundreds of French Communists were taken into custody following the riots. But Ridgway ignored the sound and fury of his detractors and immediately set to work.

His was a Herculean job to put flesh on the bones of NATO.

While Eisenhower had started the mammoth task of creating a single military command structure, Ridgway had to see the job through. This involved bringing Greece and Turkey into the NATO fold while easing the historical animosities between them, balancing British and American naval capabilities, and contradicting the conventional wisdom that all air forces ought to be united under a single command. Through deft negotiation, Ridgway knocked down these problems one by one, declaring within months: “There now exists a command structure to control our initial forces along a 4,000-mile front extending from Northern Norway to the Caucasus.”

From now on there’s a right way, a wrong way, and a Ridgway.

The next task on Ridgway’s agenda was to make sure that this long border could be defended. He pushed Allied governments to increase both their active forces and their reserve strength, build critical infrastructure to assist with troop deployment and prepare for crises through military exercises. One of his biggest challenges was to help convince France that West Germany should be allowed to rearm, while in parallel, measures were being taken to integrate the country into a western defence community.

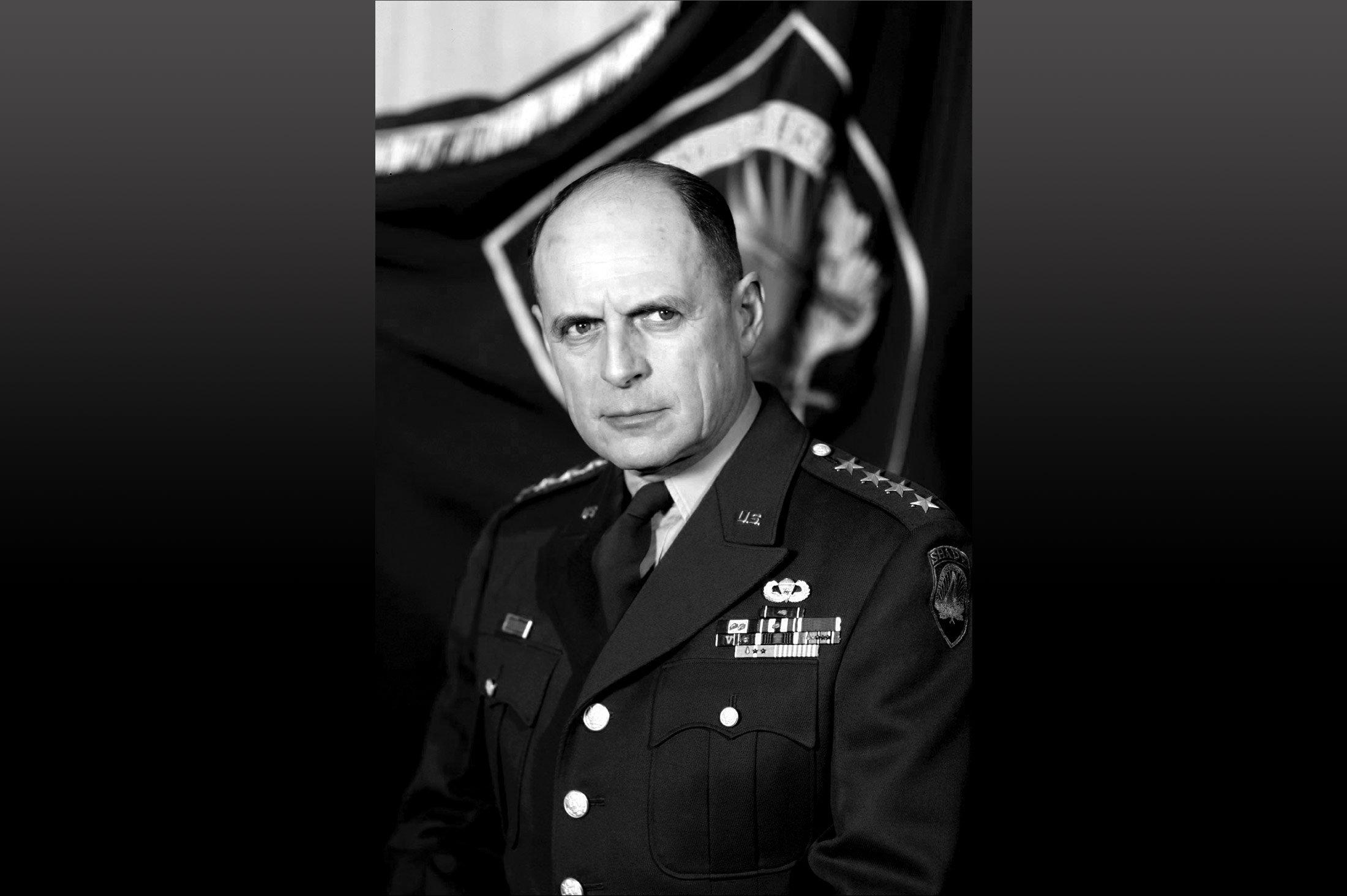

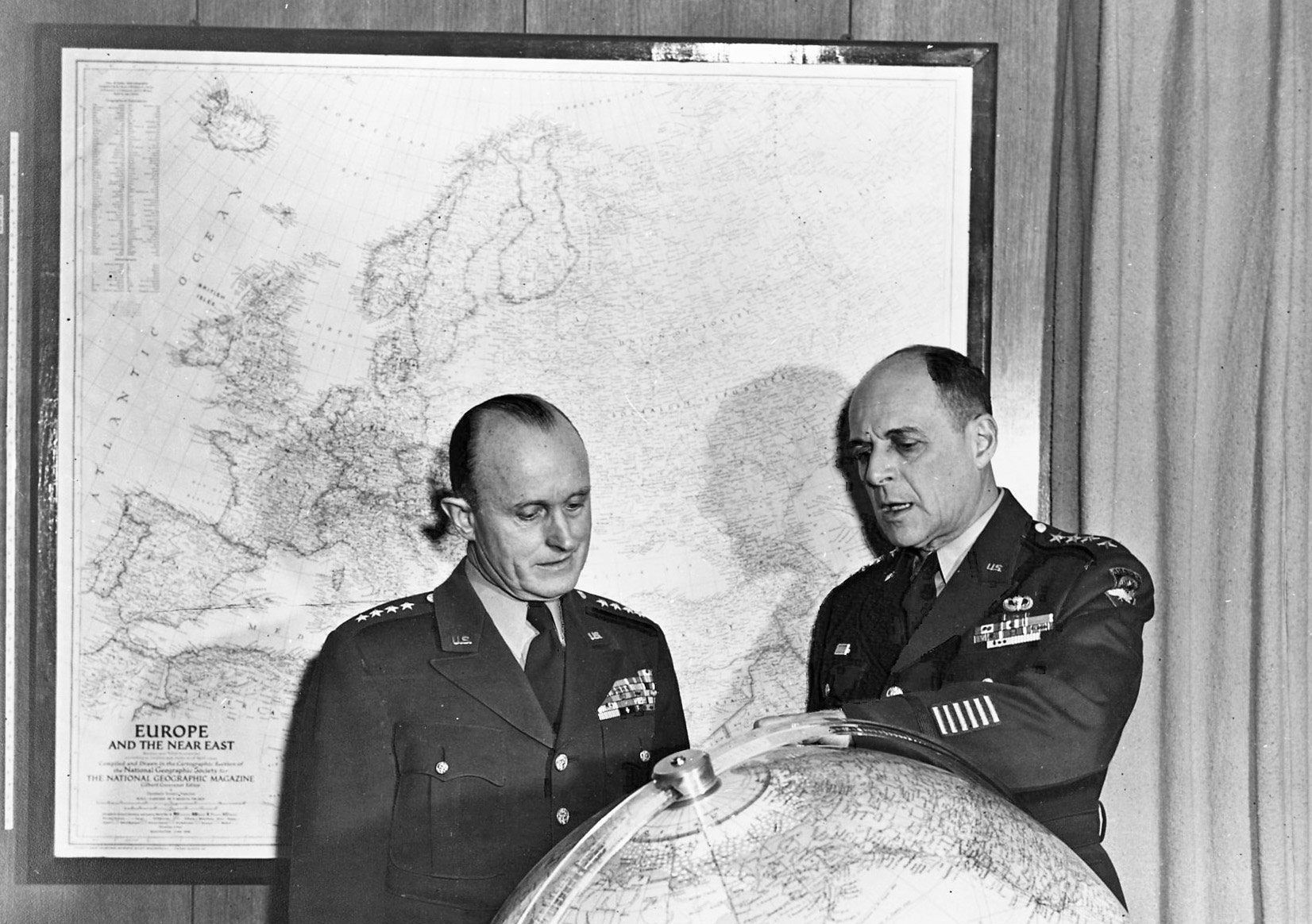

Ultimately, although he spent just over 400 days as SACEUR, Ridgway laid the groundwork for the Alliance’s growth into a successful military organisation. He boosted NATO’s regular and reserve forces from 12 to 80 divisions, created an effective command structure and mediated tensions between sometimes uncooperative and uncommunicative member states. Ridgway left NATO in July 1953 (Ridgway (right) can be seen with his successor General Alfred Gruenther in the photo below) and returned to Washington, D.C. to become the Chief of Staff of the US Army. He proved just as willing to reject orthodoxy and ruffle feathers at the Pentagon as he had been at NATO—most notably by pushing hard against the plan to send American troops to Vietnam. His views were mostly dismissed and he retired shortly thereafter.

In the end, Ridgway was proudest of the times where he used his stubbornness and indomitable personality to speak truth to power. He was not loved like Eisenhower. He was not admired like Gruenther. But he happily sacrificed the approval of his peers for something far more valuable: the lives of his troops.

I shall go to my grave humbly proud of the fact that on at least four occasions I have stood up at the risk of my career and denounced what I considered to be ill-considered tactical schemes, which I was convinced would result in useless slaughter.