There are no borders for this man.

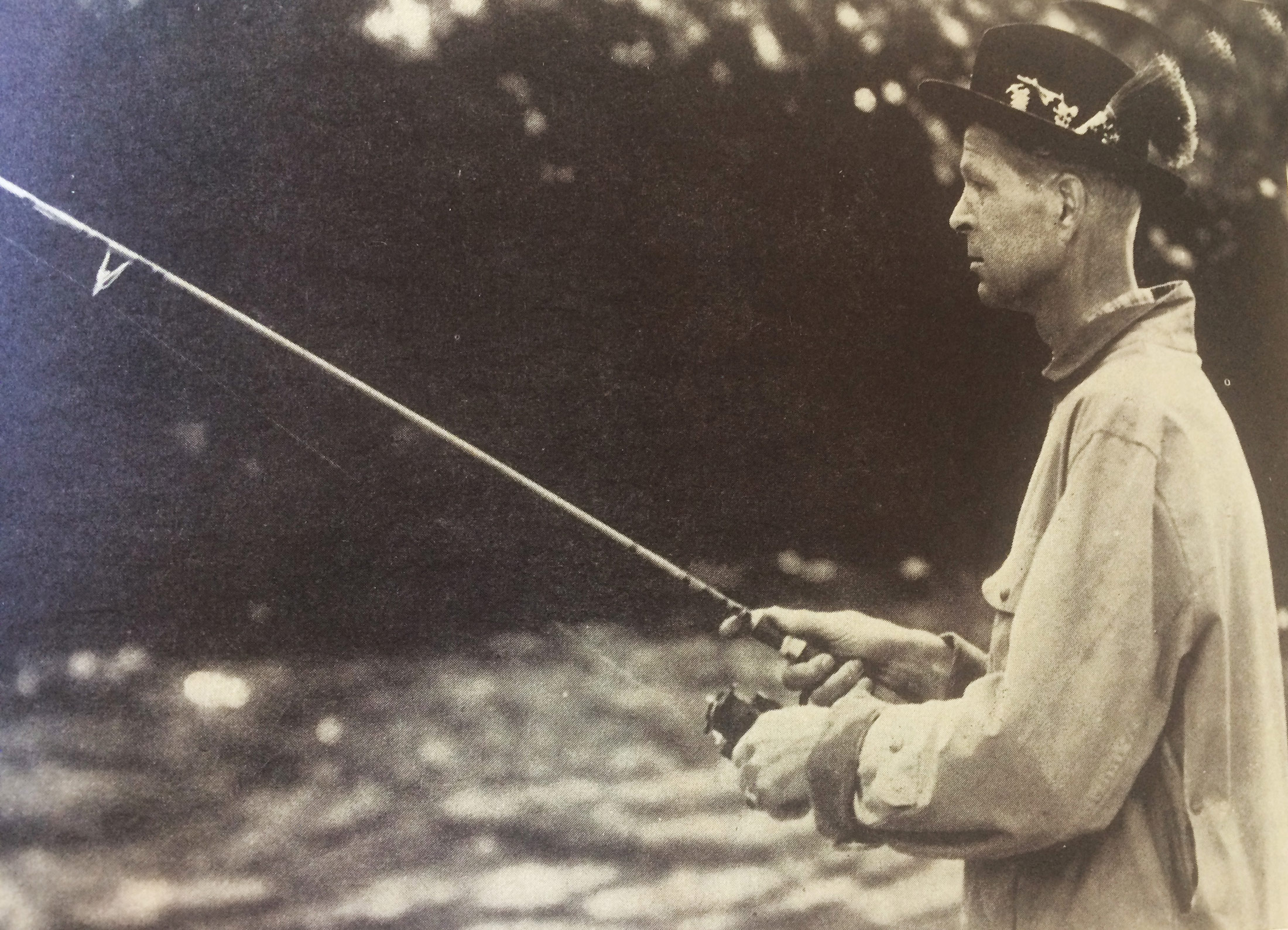

Norstad wore ''three hats'' as NATO's SACEUR, the US Commander in Chief in Europe (USCINCEUR), and as the head of LIVE OAK. These roles involved different demands, but for Norstad being SACEUR took priority. According to the New York Times, ''General Norstad saw his own role as that of an international Allied servant, and not only a United States general.'' Norstad's peers at NATO described him in similar terms. A SHAPE colonel remarked that Norstad "is not conspicuously American. He never makes a move that, of itself, gives a clue to his nationality."

This trans-Atlantic quality appeared not only in Norstad's demeanour, but also in his internationalist schedule. Norstad travelled extensively across the countries of the Alliance, speaking to audiences about the vital role that NATO played in their national and personal security. The only Air Force man to have held NATO’s top military post until the new millennium (his three predecessors and 11 subsequent successors all being Army men), Norstad had no problem jumping on a plane and crisscrossing Europe on a moment’s notice. Having this literal bird’s eye view of the Alliance reinforced the interconnectedness of NATO's Allies and the crucial importance of unity.

There are few sights more beautiful than a flag in the wind. When I look at the flags of the 15 nations that constitute NATO, I would say, ladies and gentlemen, that you are looking at the hopes of the Western world.

Ultimately, Lauris Norstad oversaw NATO's military forces during a tumultuous period. His term saw the Soviets launch Sputnik, conflict with Charles de Gaulle over France's nuclear programme, and increased Cold War tensions after the downing of an American U-2 spy plane over the USSR. But through all of this turbulence, Norstad's main achievement was keeping the Alliance together and explaining its importance to NATO citizens.

I get my formal directives on a piece of paper which I receive from the NATO Council. But my real directive is the confidence that nations place in this agency.