Recent events have solidified the Baltic Sea as an area of critical strategic importance. It serves as a vital maritime trading route, hosts considerable networks of Critical Undersea Infrastructure (CUI), and holds significant potential for the development of new sources of energy. As a result, it is also an area which is highly vulnerable to the increasingly prevalent threat of hybrid attacks – that is, attacks just below the threshold of kinetic warfare, which blur the lines between peace and conflict, such as the sabotage of critical infrastructure.

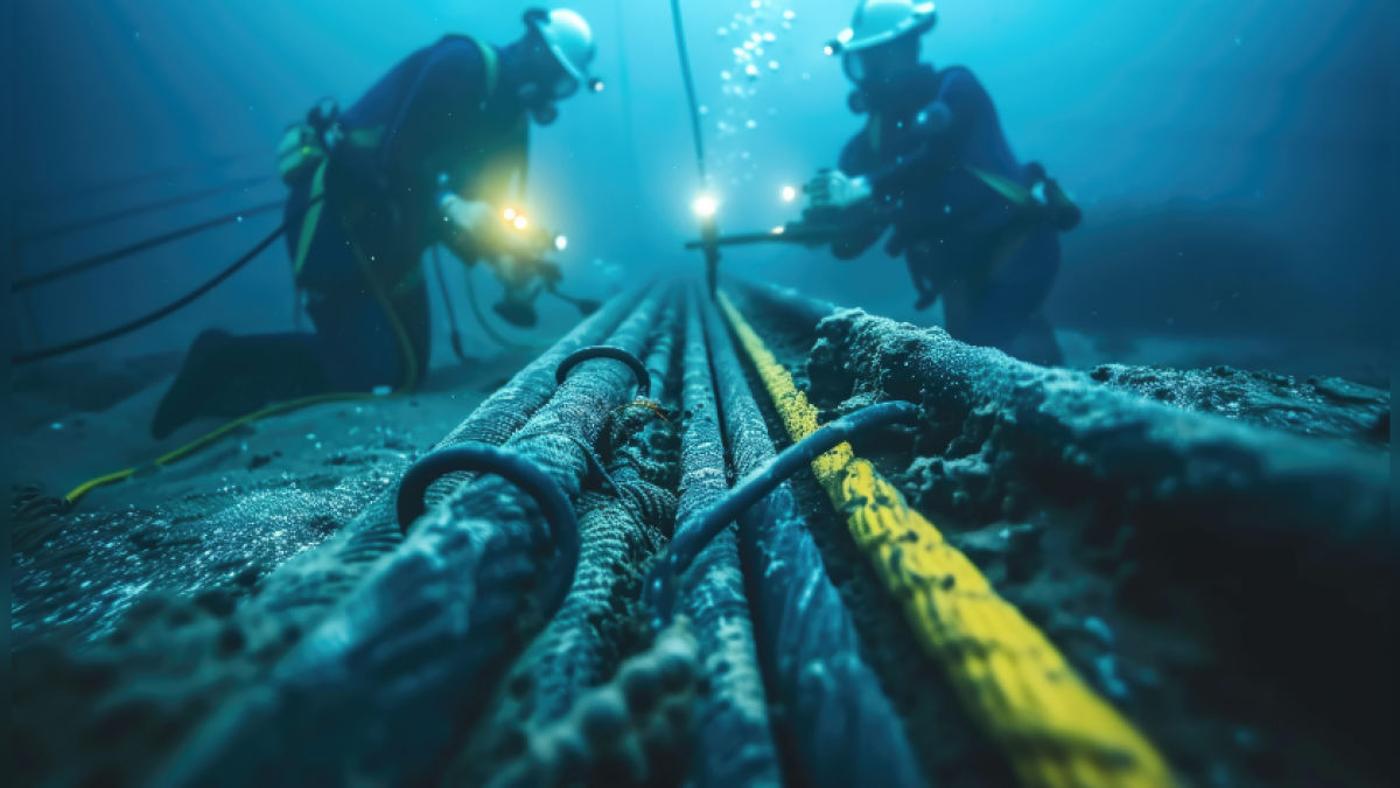

Notably, over the past 15 months, at least 11 undersea cables, crucial for international communication and energy transmission, have been damaged, raising concerns about deliberate sabotage or hostile grey zone activities from state and non-state actors. Recent incidents also provoked Euro-Atlantic discussions about the vulnerabilities of energy links and CUI in the region, firmly placing the Baltic Sea in the international spotlight and highlighting its strategic importance.

Critical undersea internet cables in the Baltic Sea undergoing repairs after they were severed in separate incidents in November 2024. © Capacity Media

The Alliance’s focus has particularly shifted towards the region since the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO (which has led some to nickname the Baltic Sea ‘NATO’s lake’). The changed security environment requires a more proactive response from NATO following recent incidents of damage to undersea communication and energy cables, cyber attacks on major European ports, ‘shadow fleet’ ships from hostile states, coordinated information threats and Russia's continued full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine. In response, NATO has adopted a ‘deterrence by denial’ posture, encapsulated by the strategic logic of ‘repel, don't expel’. This strategy emphasises the need to proactively deter aggression by stepping up the Alliance’s military presence in the region and underscoring that any attack will be met with a swift and robust response, as opposed to reacting to an attack once it’s too late to thwart.

Deterrence redefined: NATO’s strategic pivot in the Baltic region

NATO’s Madrid Summit in 2022 marked a decisive turning point in NATO’s collective deterrence and defence posture, particularly along the Alliance’s eastern flank. In its 2022 Strategic Concept, NATO formally identified Russia as “the most significant and direct threat” to Allied security and the broader Euro-Atlantic area. This recognition catalysed a shift from a posture of reassurance – characterised by a small number of forward-deployed battlegroups acting as a ‘tripwire’ - towards one of robust forward defence, requiring a larger and stronger defensive counterweight to any potential aggression. The objective is to repel, not merely respond to, aggression from the outset, reassuring NATO populations and reaffirming NATO’s readiness and willingness to defend its area of responsibility against potential adversaries.

However, this transformation is not just limited to traditional military threats. Since the Baltic region has equally become a frontline for hybrid warfare, the urgency of addressing non-kinetic threats has also informed NATO’s broader deterrence posture. These developments were reflected in 2024 with NATO's first-ever Digital Transformation Implementation Strategy - a comprehensive plan to modernise the Alliance's digital infrastructure and capabilities - and its strategy for countering hybrid threats, which outlines NATO's response to non-kinetic threats such as cyber attacks and information threats. The strategy for hybrid threats also emphasises the protection of critical infrastructure, including subsea cables and energy nodes, as a pillar of collective defence. This adopted ‘deterrence by denial’ has expanded in the hybrid space to encompass updated early warning systems against hybrid attacks, strengthened civil-military cooperation, and improved situational awareness in the maritime and cyber domains.

Poland: the eastern fortress

As a NATO Ally along the easternmost border of the Alliance, Poland acts as a logistical hub, hosts Allied troops within a NATO multinational battlegroup, and is a growing naval power. Poland's investment in maritime situational awareness tools, naval bases along the Baltic coast and strategic energy infrastructure - including its LNG terminal in Świnoujście and offshore wind farms - make it a key regional actor. Poland’s advanced renewable energy efforts in the Baltic Sea region make the country a critical leader in the goal amongst NATO countries of diversifying energy sources and becoming independent from Russian fossil fuels.

The Polish frigate ORP Generał Tadeusz Kościuszko makes her way through the Baltic Sea during BALTOPS 23 © The Polish Navy

In the face of growing military and non-military threats, not least of which is Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, which continues to play out along Poland’s eastern border, Warsaw decided in 2024 to a significant and unprecedented increase in its defence spending. It now allocates more than 4% of its GDP to military modernisation - the highest, as a percentage of its GDP, among all NATO member countries. In particular, Poland's acquisition of modern systems such as the MIECZNIK frigates and Patriot air defence batteries, provides a strong example of the country’s commitment to integrated deterrence and defence, including in the maritime domain.

Polish military initiatives, which are further enabled by its increased defence spending, complement NATO exercises and strengthen NATO's air policing and naval presence in the Baltic Sea. As a result, Poland is establishing itself as a regional security provider with a strong defence and deterrence strategy for the collective security of all NATO Allies bordering the Baltic Sea. In particular, Poland is working in close cooperation with Germany - a country which has also recently taken important steps to increase its defence expenditure and its military capabilities – as part of the German-Polish Action Plan. Launched in July 2024, the Action Plan established intensified cooperation between the Polish and German navies in the Baltic Sea region and a commitment to enhance Allied land and maritime Command and Control (C2) through a new NATO naval command centre in Rostock, which opened in October 2024. Germany and Poland also take part in the annual multinational exercise BALTOPS, which demonstrates Allies’ shared commitment to strengthening NATO’s readiness in the region. BALTOPS 2024 involved 20 countries and more than 9,000 personnel.

Integration and innovation: the Nordics

The accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO has transformed the power dynamics of the Baltic Sea. What was once a geographically vulnerable area for NATO has become a near-enclosed Allied maritime zone, turning the Baltic into a defensible space and tightening the Alliance’s defence and deterrence posture.

Finland’s extensive border with Russia, robust territorial defence model, and advanced air forces (including F-35s) enhance NATO’s deterrence posture. Moreover, Finland’s national energy strategy, which is built on diversified sources, cross-border grid connectivity, and strong cyber-physical protection, has emerged as a resilience benchmark. The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung report Energy Without Russia: The Case of Finland notes that Finland’s model offers critical lessons for NATO, particularly in ensuring that energy systems can withstand cyber intrusions and sabotage, which are growing components of Russia’s hybrid playbook.

A Swedish CB90-class fast assault boat during exercise Steadfast Defender on 6 March 2024. Sweden has recently participated in BALTOPS for the first time as a NATO member

© Danielle Serocki / U.S. Navy

As for Sweden, alongside its considerable naval power, the country is a leader in corporate renewable energy sourcing through Power Purchase Agreements. These types of agreements, which are particularly prevalent in energy-intensive industries like the production of paper, steel, and automobiles, provide long-term financial assurances to renewable energy producers, encouraging investment and, thus, increasing supply. This strengthens NATO’s energy resilience and independence.

Denmark also provides significant contributions to NATO’s defence with its advanced frigates and its specialist capabilities in anti-submarine warfare. Together with Norway, Denmark is a gatekeeper of the High North, and complements Baltic security with its domain expertise in undersea infrastructure protection, notably through advanced sonar networks and partnerships with the private sector. Despite not bordering the Baltic Sea itself, Norway’s proposal to establish a NATO hub for safeguarding Critical Undersea Infrastructure in the North Atlantic and the Arctic reflects a growing recognition that hybrid threats are interconnected, trans-regional and cross-domain.

Equally, the Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO), which is now fully interoperable within NATO’s framework, strengthens joint operational planning and information-sharing, including cyber defence and civil-military coordination. This institutionalised cooperation adds cohesion to the Baltic Sea’s broader security architecture, enabling a rapid response to hybrid incidents—be it a cable cut, a cyberattack, or an information threat.

Small nations, smart defence: the Baltic countries

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are indispensable actors in NATO's deterrence strategies. Despite their smaller territorial sizes, these Baltic countries have made significant strides in military preparedness, societal resilience, and host-nation support since their accessions to NATO.

Each of the three countries proudly hosts a NATO multinational battlegroup, featuring robust contributions from other Allies including Germany, Canada, and the UK, among others. As part of NATO's innovative force model, these battle groups are being transformed into brigade-level formations equipped with comprehensive combat support and essential assets. They also complement the multinational battle groups deployed in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Slovakia within NATO’s enhanced Vigilance Activities framework.

In addition to their conventional military capabilities, the Baltic countries are at the forefront of civil defence, cyber resilience, and countering hybrid threats. Lithuania has launched a National Cyber Security Centre, Estonia houses the NATO Centre of Excellence for Cyber Defence Cooperation (CCDCOE), and Latvia hosts the Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence. As an example of the impact of these bodies, the CCDCOE has conducted various emergency operations tests to help prepare for potential targeted hybrid attacks on energy systems and cyber domains based on previous incidents of sabotage in the region.

In addition, the recent disconnection from the former-Soviet BRELL energy grid should be considered a historical milestone as it integrates the Baltic countries into the shared synchronous grid of continental Europe and decouples their energy infrastructure from that of Belarus and Russia, strengthening their strategic autonomy.

Protecting vulnerable Critical Undersea Infrastructure

The vulnerability of subsea infrastructure, including cables, pipelines, and energy assets, has become a central concern for NATO and Allies. The sabotage of the Nord Stream and Balticconnector gas pipelines, several cable severances over the last few months, and the discovery of the Russian shadow fleet in the Baltic basin have all served as wake-up calls, demonstrating how hybrid attacks can cause strategic disruption without overt military confrontation.

In response, NATO established a Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cell at NATO Headquarters in Brussels. It also launched a Maritime Centre for the Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure in its Maritime Command in Northwood, UK, which enhances intelligence-sharing and incident response. In addition, in January 2025, NATO launched Baltic Sentry, a new military activity in the Baltic Sea which aims to improve Allies’ ability to respond to destabilising acts. The activity brings together Allied navies, maritime surveillance assets, and private sector operators to ensure real-time situational awareness and rapid response capabilities across the Baltic Sea’s vulnerable zones, strengthening the Alliance’s deterrence and defence posture.

Equally, NATO projects like HEIST, which aims to reroute critical communications via satellites, and the first-ever meeting of NATO’s new Critical Undersea Infrastructure Network in May 2024 indicate a broader strategic shift and highlight how protecting seabed infrastructure is now integral to NATO’s hybrid defence strategy.

Conclusion

Ultimately, NATO's deterrence strategy in the Baltic Sea depends on its persistent military presence and enhanced situational awareness. The Alliance maintains a strong maritime posture through its two North Atlantic-focused standing naval forces, Standing NATO Maritime Group 1 (SNMG1) and Standing NATO Mine Counter Measures Group 1 (SNMCMG1), which have contributed to recent exercises like BALTOPS and the Baltic Sentry activity. These exercises and activities test high-end warfighting and hybrid defence capabilities, integrating the air, land and sea forces of NATO Allies. Anticipating multi-domain operations, they also include scenarios such as cyber attacks and infrastructure sabotage, ensuring readiness across domains. Finally, through the 2023 Digital Ocean initiative, NATO is enhancing maritime awareness through data sharing with partners and industry. Within this framework, real-time shipping tracking, seabed mapping, and cyber tools connect navies, coast guards, and commercial operators in a shared operational picture.

19 NATO Allies, more than 50 ships, more than 85 aircraft, and approximately 9,000 personnel participated in BALTOPS 2024. Photo © NATO / MARCOM

In today’s changed security environment, protecting Critical Undersea Infrastructure has become an integral pillar of deterrence. And in response to increasing hostile activities in the Baltic Sea by adversaries, NATO is providing a robust response. Its Maritime Command (MARCOM) and the Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cell are leading efforts to secure critical seabed assets like pipelines and cables, and the Allies communicate unity and preparedness by training in mine warfare, amphibious landings, and anti-submarine operations.

As NATO marks 76 years of collective deterrence and defence, Allied cooperation in the Baltic Sea is testament to the strength of unity and collective determination in the face of all potential threats to the region. As the 2022 NATO Strategic Concept correctly identifies, “maritime security is key to our peace and prosperity”, and, quite simply, NATO’s enhanced response to traditional military and hybrid threats in the Baltic Sea is of existential value for the security of the European continent and the wider Euro-Atlantic area.