Would NATO be ready to deal with the level of military might on display during Exercise Vostok (“East”) in September 2018, if Russia were to deploy a similar number of troops and equipment along its western borders? Does NATO have the military strength and mobility to match such a show of force? Could Allies provide the necessary infrastructure to support a military deployment on this scale? Does the Alliance have an adequate response for the hybrid tactics that Russia would be likely to employ?

Readiness has been at the top of NATO’s agenda since 2014. But a look back over the past seven decades of the history of the Alliance shows that many of the current issues surrounding readiness, successful deterrence and reassurance are not new.

According to Russia’s senior military leaders approximately 300,000 troops – as well as 1,000 fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, 80 ships, and 36,000 tanks, armoured and other vehicles – participated in VOSTOK 2018, an exercise unprecedented in scale since the Cold War.

© Modern Diplomacy

The way it was

It is said that, for 40 years, NATO successfully did what it was established to do. It had a singular strategic aim: to deter a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. The Allies had no doubt about the threat to their national security and that it had to be matched by the necessary forces, which would persuade Moscow the Alliance was credible.

But is our memory entirely accurate? Contrary to common belief, it is also important to note that NATO, from its outset, did not have a single purpose. In fact, the Alliance’s creation was part of a broader effort to serve three purposes: deterring Soviet expansionism, preventing the revival of nationalist militarism in Europe, and encouraging European political integration.

In the post-Second World War years, Western European nations faced a political and economic dilemma. Governments changed and had little interest in military spending – indeed, they were under considerable pressure from across the Atlantic to settle the debts that had arisen from the United States’ commitment to its European allies. Effectively, this was Peace Dividend Number One, and Allied troop numbers in Europe dropped from around 4.5 million in May 1945 to less than one million by the end of 1946.

The very establishment of the Alliance was such a strong reassurance measure that its member states were soon clamouring for further cuts to military forces, arguing that NATO provided such a strong political deterrent that a military presence in strength was not necessary. This was Peace Dividend Number Two! To some extent, the Korean War reversed that thinking because of fears that Moscow would take advantage of the deployment of large numbers of forces on the Korean peninsula to launch an attack against Western Europe. This led to the agreement of ambitious NATO force goals at the Lisbon meeting in 1952 but it soon became clear that these could not be met.

Somewhat ironically, as a consequence of the Soviet Union’s nuclear build up following its detonation of a nuclear weapon in 1949, NATO’s policy of “Massive Retaliation” was also quoted as a reason why a build-up of conventional forces was not necessary. Allies were simply not prepared to meet the costs involved and, as the Alliance approached its third birthday, it was already learning that political ambition was one thing – putting boots on the ground was something else.

NATO settled into its “New Look” policy throughout the 1950s, which aimed to give greater military effectiveness without having to spend more on defence. This, of course, demanded an absolute reliance on the nuclear capability of the United States and, with the slight exception of France and the United Kingdom, European Allies were more than content to live under the perceived security of the ‘Transatlantic Umbrella’.

Throughout the 1960s, NATO embraced détente as a political tool to enhance dialogue with Warsaw Pact countries. Despite the Cuban missile crisis, and tensions over Vietnam, a cautious dialogue was established with Moscow. “Massive Retaliation” gradually became “Flexible Response”, which put greater emphasis on the need for robust conventional forces.

A main battle tank (M60A3) of the 3rd Armored Division drives through the Fulda Gap – an area between the Hesse-Thuringian border and Frankfurt am Main that contains two corridors of lowlands through which tanks might have driven in a surprise attack effort by the Soviets and their Warsaw Pact allies to gain crossing of the Rhine River – 1985. © US Army

So, by the mid 1980s, NATO’s 16 member states could claim a military strength of over five million personnel. At the peak of the Cold War, just under three million personnel and 100 army Divisions were on the ground in Europe and committed to NATO. A further 30 Divisions and 1.7 million personnel were at high readiness. More than 400,000 US personnel were based on the European continent.1 NATO was ready, but for only one scenario.

Conceptually speaking

Large international organisations are often resistant to change. However, in November 1991, six months after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, NATO issued its new Strategic Concept as a public document for the first time. It set a new tone and the opening words of its conclusion are significant:

"This Strategic Concept reaffirms the defensive nature of the Alliance and the resolve of its members to safeguard their security, sovereignty and territorial integrity. The Alliance's security policy is based on dialogue; co-operation; and effective collective defence as mutually reinforcing instruments for preserving the peace. Making full use of the new opportunities available, the Alliance will maintain security at the lowest possible level of forces consistent with the requirements of defence. In this way, the Alliance is making an essential contribution to promoting a lasting peaceful order."

This was a very clear message that NATO’s military footprint in Europe was about to reduce significantly (the best-known Peace Dividend) and signalled that the Allies intended to develop close ties with former adversaries.

Following the collapse of the Warsaw Pact in March 1991, foreign ministers and representatives of 16 NATO Allies and nine Central and Eastern European countries attend the inaugural meeting of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council in December 1991. On the same day, developments in Moscow marked the effective end of the Soviet Union. © NATO

NATO’s next Strategic Concept was published in 1999, coincident with the 50th anniversary of the Alliance. Not surprisingly, it committed the Allies to common defence and peace and stability of the wider Euro-Atlantic area. Importantly, it identified new risks that had emerged since the end of the Cold War, including terrorism, ethnic conflict, human rights abuses, political instability, economic fragility, and the spread of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons and their means of delivery. The strategy called for the continued development of the military capabilities needed for the full range of the Alliance’s missions, from collective defence to peace-support and other crisis-response operations. NATO was, in effect, asking its members to do more, militarily, across a wider geographic footprint.

NATO’s current Strategic Concept, published in 2010, lays out the Allies’ vision for an evolving Alliance that will remain able to defend its members against modern threats. It commits NATO to become more agile, more capable and more effective, urging Allies to invest in key capabilities to meet emerging threats. It highlights the need for NATO to remain ready to play an active role in crisis-management operations, whenever it is called to act.

This is an ambitious global outlook which requires firm commitment and investment by member states. But at the same time, it was agreed during a period of significant austerity; it points to the need for NATO to remain cost-effective and makes continuous internal reform a key aspect of the way the Alliance will do business in the future.

NRF – Not Really Functional?

During the Cold War, NATO had the luxury of knowing where it would be fighting, should the need arise. It made sense to maintain high levels of in-place forces and allow them to train for battle on the very ground on which they would ultimately have to fight. More than three million troops were on the ground in Europe, but more than half that number again were at a high state of readiness away from the theatre of potential operations.

A consequence of the drawdown of US forces in Europe in the 1960s and 1970s was the commitment to reinforce in-place forces rapidly and robustly should the need arise. The term “REFORGER” (Return of Forces to Germany) is now becoming a distant memory but it really should have a more prominent place in military history than it currently enjoys. In 1988, 125,000 personnel deployed across the Atlantic within 10 days. But it is not just the ability of military forces to react quickly that makes REFORGER so impressive. A deployment of this scale requires the mobilisation of civilian strategic transport assets, and the infrastructure to receive and re-deploy those forces on arrival on European soil. It is not just about military preparedness; civil preparedness is equally important.

In 1988, 125,000 personnel deployed across the Atlantic within ten days under “REFORGER” (Return of Forces to Germany), the US commitment to reinforce in-place forces rapidly and robustly should the need arise. © NATO

In addition, the Allies recognised that NATO’s flanks were a weak point. The Allied Command Europe Mobile Force was established in 1960 as a multinational immediate reaction force that could be sent at very short notice to any part of Allied Command Europe under threat. Its mission was to demonstrate the solidarity of the Alliance, and its ability and determination to resist all forms of aggression against any Ally. The greatest strength of the Mobile Force was that it was formed from national units that were permanently earmarked for that purpose, selected to meet the requirements of a particular task, and exercised regularly in that role. The Force was dissolved in 2002 in the flawed belief that its capabilities would be incorporated into NATO's new concept of graduated readiness forces.

Thus, in November 2002, at the Prague Summit, Allied leaders agreed to “create a NATO Response Force (NRF) consisting of a technologically advanced, flexible, deployable, interoperable and sustainable force including land, sea, and air elements ready to move quickly to wherever needed, as decided by the Council.”

However, it was not an easy birth. The decision was taken at a time when a number of Allies were heavily engaged in coalition operations outside the traditional NATO theatre. The concept of the NRF was (and is) that nations declare their forces for a six-month period. This raises a number of issues.

The first issue is the problem of continuity. Units are not permanently earmarked for NRF duties, so it is not a focus of their routine national training.

Second, many of the “technologically advanced” capabilities are in high demand and often unavailable. Force generation of NRF capabilities has largely been disappointing. At times, only 60 per cent of the required capability has been made available by contributing nations – often the critical enabling capabilities are the most difficult to source.

Third, funding of NRF – in accordance with traditional NATO policy – was agreed on the basis that “costs would lie where they fall”. This principle was tested when it was agreed that the NRF should be deployed in support of earthquake-relief efforts in Pakistan in late 2005. The nominated lead nation for that NRF rotation refused to bear the costs and a lengthy political debate ensued. So, the first operational use of the concept failed the “high readiness” test, underlining the need for funding reform.

Valiant attempts have been made to keep the NRF relevant. Significantly, the 2014 Wales Summit saw an agreement to enhance its capabilities in an effort to adapt and respond to emerging security challenges posed by Russia, as well as risks emanating from the Middle East and North Africa. Subsequently, a decision was taken to establish a Very High Readiness Joint Task Force within the NRF structure and to increase the size of the NRF to 40,000.

NATO’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force – a rapidly deployable, multinational force made up of air, land, maritime and Special Operations forces – was established following decisions to improve Allied readiness taken at the 2014 NATO Summit in Wales. © EU Today

However, successfully implementing these decisions requires that contributing nations step up their commitment to provide the necessary forces. To date, that level of commitment has not been forthcoming. This undermines NATO’s credibility and calls into question its ability to deter aggression.

Keeping up standards

One of NATO’s greatest strengths during the Cold War era was interoperability: “the ability to act together coherently, effectively and efficiently to achieve Allied tactical, operational and strategic objectives.”

The Alliance had for many years placed great emphasis on standardised doctrine, which was to become an essential element of command and staff training in all member countries. Tactics techniques and procedures were also standardised and units exercised frequently with their colleagues from other nations. Everything from ammunition, to fuel, to communications was compatible across all NATO assigned units. In fact, NATO standardisation was so successful that certain standards, such as aircraft refuelling connectors, were adopted by the Soviet military authorities.

NATO also had a strict programme of evaluation. Units declared available to NATO were subject to rigorous checks, often at no notice, to ensure that the standards set were maintained.

However, the 1990s saw the start of a gradual erosion of the very tight standards that had been employed until then. NATO-led operations in the western Balkans were based on the allocation of a particular geographical area to one lead nation with very little multinationalism within these areas. Similarly, at that time, little NATO doctrine was available that reflected Alliance policy for peacekeeping and post-conflict peace support, so individual nations tended to fall back on national policy and experiences.

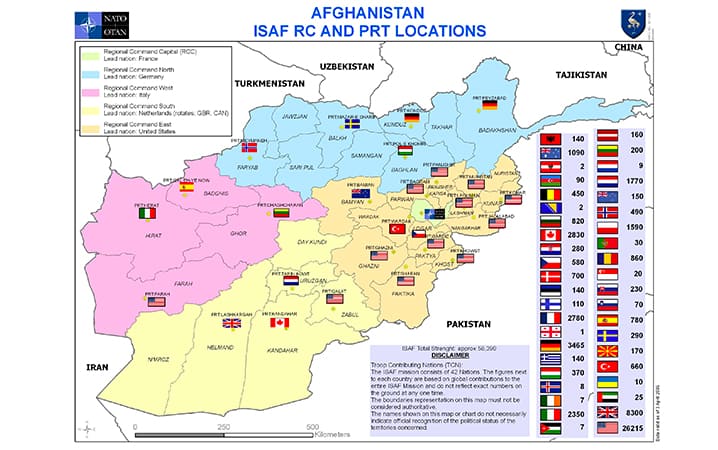

This theme continued as NATO began its engagement in Afghanistan. The Allies adopted the concept of “Regional Leadership” whereby a “Lead Nation” pulled together a rather disparate group of nations, including operational partners that had never before been associated with a NATO operation. The Afghanistan theatre introduced additional complications. The specific requirements for operating in that theatre were such that many nations procured specialist equipment under urgent operational measures. These met national requirements but equipment and then tactics, techniques and procedures became less standardised across the theatre.

Map of Afghanistan showing the “Lead nations” of the Regional Commands of the International Security Assistance Force (7 April 2009). © NATO

Moreover, NATO-led missions and operations are increasingly being set up alongside coalition efforts. This causes confusion, both at the headquarters level and in the field, with personnel (and even theatre commanders) not sure whether they are working to national or NATO policy.

At the 2010 Lisbon Summit, Allied leaders stated that: “We will preserve and strengthen the common capabilities, standards, structures and funding that bind us together.” One can argue that NATO is failing to live up to that pledge.

Lack of commitment

Readiness is not easy to define. To judge the readiness of NATO forces, one must take a comprehensive view that takes into account both the operational and the organisational, or strategic, perspectives. At the unit level, readiness is about equipment, manning, training and interoperability. At the organisational level, readiness can be simply defined as “the ability of military forces to fight and meet the demands of assigned missions.2”

Readiness comes down to one simple question: are we ready to win the next fight? But, to answer that question, it is necessary to know four things: what, when, where, and how.

In the Cold War era, this task was relatively easy. We might not have known when our military capabilities were required but we had a pretty good idea of what they would be required to do, and where and how they would do it. The unknown “when” was easily resolved by keeping the necessary forces on the ground in Western Europe at a high level of “readiness” and being prepared to reinforce those in-place units rapidly with equally “ready” forces.

Today, however, the uncertainty of the modern world (not to mention the pressure on national budgets) and the lack of an obvious and immediate threat to the territory of some of NATO’s member states, makes it difficult for them to make the necessary commitment. If Allies cannot commit to fund their defence forces properly, then it is unlikely that they will take the additional steps to prepare and commit them to NATO’s command and control.

This is why the present occupant of the White House, and his predecessor, have complained loudly about other Allies’ lack of commitment, and have attempted to define targets that might persuade their fellow heads of state and government to increase their level of commitment. Nevertheless, let us be absolutely clear on one point: the United States will not spend one cent of its defence budget unless it is in the interests of its own national priorities.

Again, though, this is not a new issue. In 1954, United States Secretary of State John Foster Dulles warned that: “If the European Defence Community should not become effective […], there would indeed be grave doubt as to whether Continental Europe could be made a place of safety. That would compel an agonizing reappraisal of United States policy.”3

More recent, and better known, is the agreement on defence spending reached by Allied leaders at the Wales Summit, namely that the Allies will “aim to move towards the 2% [of GDP] guideline within a decade.” This is classic communiqué language. It leaves Allies with plenty of ‘wiggle room’ and presents an ambition that goes well beyond the attention span of most politicians.

More important perhaps but seldom quoted is the communiqué language that follows: “…. with a view to meeting their NATO Capability Targets and filling NATO’s capability shortfalls”. Because it does not set targets within the term of current governments, or even the next, it is simply passing the buck.

Stepping up readiness

At Wales, we also saw the launch of a Readiness Action Plan. The Summit Declaration states:

“In order to ensure that our Alliance is ready to respond swiftly and firmly to the new security challenges, today we have approved the NATO Readiness Action Plan. It provides a coherent and comprehensive package of necessary measures to respond to the changes in the security environment on NATO’s borders and further afield that are of concern to Allies. It responds to the challenges posed by Russia and their strategic implications. It also responds to the risks and threats emanating from our southern neighbourhood, the Middle East and North Africa. The Plan strengthens NATO’s collective defence. It also strengthens our crisis management capability. The Plan will contribute to ensuring that NATO remains a strong, ready, robust, and responsive Alliance capable of meeting current and future challenges from wherever they may arise.”

This is brave language. It requires an enormous commitment by Allies.

Events in the Balkans, Central Asia and the Middle East have demonstrated that NATO can no longer restrict its interests to the traditional Euro-Atlantic area. However, Russia’s invasion of the Crimean peninsula and continued activity in eastern Ukraine as well as its provocative military activities near NATO’s borders have shown that deterrence and defence remain as important as ever. So, in a world of shrinking defence budgets and changing political priorities, NATO has now committed itself do to what it was established to do and much more besides.

NATO’s strength will always be strategic. But to be credible it must have the ability and the will to defend its territory collectively as a last resort. For that, its member nations must demonstrate the necessary resolve.

While that commitment has been slow to materialise, steps are being taken to strengthen the Alliance’s readiness to fulfil its full range of obligations, and an improvement in coherence is visible.

A British Army convoy crosses the Øresund Bridge, which connects Denmark and Sweden, during a 2,000-km journey from the Hook of Holland to Norway for NATO exercise Trident Juncture 2018. Demonstrating the ability to move Allied forces into and across Europe at speed, and sustain them, was an important part of the exercise. © NATO

Military mobility is now a key focus of cooperation with the European Union. Moving Allied forces into and across Europe at speed, and sustaining them, is a significant logistic challenge involving many stakeholders at national and multinational levels.

NATO defence ministers endorsed a new US readiness initiative, at the 2018 NATO Summit in Brussels. Known as the “Four 30s”, it seeks to establish a “culture of readiness” to “provide forces [….] ready to fight at short notice, and [….] able to deploy swiftly through Europe.” The goal is to ensure that, by 2020, NATO has 30 mechanised battalions, 30 kinetic air squadrons and 30 naval combat vessels, able to be used within 30 days.

Unlike the vaguer aims for defence spending and capability targets agreed at Wales, this set of targets has a timescale that is within the term of most current NATO member governments – and therefore introduces a degree of accountability – and the targets are quantifiable.

But much more needs to be done. The Defence Planning Process should be more effective in terms of providing solid guarantees that the Supreme Allied Commander Europe will have the necessary forces and resources to do what is asked of him. This, in turn, drives the NATO force generation process that needs to be able to deliver the necessary forces quickly, without the political wrangle that has become so familiar in recent years.

Moreover, the Alliance needs to expand its relationship with member states and partner countries to develop a whole-of-government strategy to establish the relationships required to project stability successfully beyond its borders.

Finally, we might return once more to NATO’s beginnings. The following words were written in 1951. It was aimed at that time at Reserve Forces but might apply equally well to high-readiness forces in NATO’s current and future inventory:

“Reserve forces must be given refresher training annually. In this respect, it is essential that a man receives his refresher training in the actual unit in which he will be mobilized. It follows from this that all reserve formations and units must actually exist in peace and that the number of reserve formations and units to be created in totality on mobilization must be reduced to the minimum; as any system for reserve, forces which depends solely on units being formed only on mobilization is totally incapable of meeting European defence requirements.”

Painstaking progress towards these goals would help ensure that NATO will be ready to respond effectively to any threat, no matter what form it might take.

1 “U.S. Military Presence in Europe (1945-2016)”, U.S. EUCOM Communication and Engagement Directorate, 26 May 2016

2 “Defining readiness: Background and issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, 14 June 2017

3 “The ‘Agonizing Reappraisal’: Eisenhower, Dulles, and the European Defense Community”, Brian R. Duchin, 1992