According to Greek mythology, Sisyphus was a cruel king who was condemned to roll a large rock up a steep hill, only to see that rock roll down, just as he was about to reach the summit. He would then start all over again with the same result. Many have compared the relationship between the European Union and NATO as a Sisyphean task: just as some progress is achieved, all efforts seem to be in vain as things roll back, and then the process is repeated with no more chance of success.

This paradigm contains some elements of truth but it oversimplifies things. The relationship between the two organisations, whose headquarters are only five kilometres apart, was never a linear process. It has seen good days and bad days – but it has always evolved. And it keeps evolving and becoming deeper and more comprehensive. Nowadays, contacts between staff of the respective organisations are a daily occurrence that hardly raise an eyebrow. This was not the case even a few years ago, when a visit by an EU official to NATO Headquarters was a rare and significant event.

To better understand the EU-NATO relationship, we need to address three key questions:

- Why is this relationship important?

- What are the fundamentals of the relationship?

- How did the institutional relationship evolve?

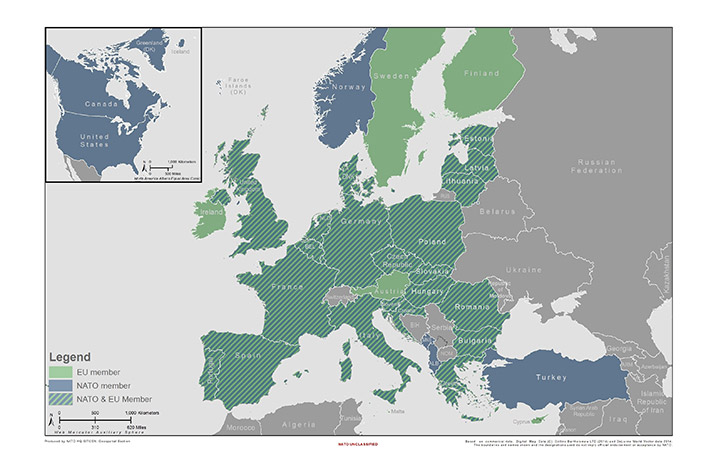

The European Union and NATO currently have 22 member countries in common (July 2019). © NATO HQ Geospatial Section

Why is this relationship important?

The short answer is: membership. From this stem values, threats and challenges, as well as competences.

NATO calls the European Union a unique and essential partner. In a sense, it is a partner, since it is a unique entity with a legal personality of its own that goes beyond the member states that compose it. But when it comes to security and defence matters, the European Union relies – at least for now – primarily on intergovernmental cooperation between its 28 member states. Therefore, the role of the members is preponderant and, right now, roughly two thirds of them belong to both organisations. Some decades ago, the overlapping membership was even stronger: until 1973, the totality of the members of the then European Economic Community were NATO Allies; from then until 1995, all but one of the EU member states were also members of the Alliance.

Decisions taken by individual nations most often have a direct impact on both organisations. If a nation that belongs to both the European Union and NATO decides to spend more on defence and develop its operational capabilities, or faces an external security threat, this has an impact on both organisations. European nations do not have two armies and two defence budgets, one for each organisation. They have a single set of forces and efforts undertaken within each organisation need to be coherent and complementary with the efforts of the other. This is easier said than done, but remains the objective.

Stemming from a large overlap of membership is the sharing of common values. Members of the European Union and NATO share a commitment to democratic principles, and the respect and protection of the rule of law and human rights. Moreover, they share a market economy, as well as a common neighbourhood, which faces common security challenges that may emanate from the East or the South. These bonds tie them even further together than does their membership of other values-based international organisations, such as the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe or the United Nations. And by extension, it means that both the European Union and NATO have a duty to cooperate to protect their citizens, as well as ensure their prosperity.

Last but not least, the two organisations have evolved in parallel and have developed special competences that allow them to protect the well-being of their citizens. NATO has a clear comparative advantage when it comes to military capabilities, especially in ensuring a credible deterrence and defence posture for the Alliance and its territory. On the other hand, while the European Union is gradually developing its military capabilities, it has a clear comparative advantage when it comes to civilian capabilities, which are wide-ranging and include economic sanctions; building resilience in spheres such as energy and cyber security; addressing disinformation; humanitarian assistance; and transport infrastructure. Given the increasingly diverse security challenges facing European nations there is a need to draw from a wide pool of different competences, whether civilian, military, or a combination of both.

What are the fundamentals of the relationship?

When speaking about the fundamental elements of EU-NATO cooperation – how the two interact – many people imagine this is mostly about the staffs of the two organisations meeting somewhere in Brussels to exchange views. While this is undoubtedly part of relations, it is actually only a small fraction of what is going on. The relationship is above all political – it is not limited to what the respective staffs do together, though this has been almost the exclusive focus of how we perceive relations. Rather, it is about what the two organisations can do independently of each other, but in a broadly coordinated and complementary way, to achieve the same objectives.

Since their inception, the key objective of both the European Union and NATO has been, and continues to be, the preservation of peace in Europe, as well as the promotion of the stability and prosperity on the continent and beyond.

For this reason, the foundation of EU-NATO relations should be considered to be 30 August 1954. That was the day that the French National Assembly failed to ratify the Treaty establishing the European Defence Community, which contained concrete provisions for the establishment of a European army.

From that moment on, NATO became the sole provider of military deterrence and defence in Europe, under whose protective umbrella, the European Economic Community was founded and prospered. The two organisations did not necessarily speak to each other but they were interdependent. One provided security and defence. The other helped build economic prosperity, which in turn helped solidify the foundations of common values, but also allowed European nations to gradually contribute a bigger part in sharing the burden of European security and defence.

Following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, the European Union and NATO worked in tandem, albeit in parallel, to promote the integration of countries of Central and Eastern Europe into the Euro-Atlantic institutions and their return to the wider European family of democratic nations. They also cooperated to contain the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. These endeavours continue to this day, as both organisations continue their efforts to foster stability, development and reform in the Western Balkans and beyond.

A ceremony at Camp Butmir, on 2 December 2004, marks the end of the NATO-led Stabilisation Force’s mission and the establishment of EU operation Althea. EUFOR is still deployed in Bosnia and Herzegovina today. © NATO

More recently, the European Union and NATO, acting in parallel, have responded to threats emerging from the East. In the wake of Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and destabilizing activities in Eastern Ukraine, EU sanctions were imposed on Russian individuals and entities deemed responsible, as well as on specific economic sectors. Meanwhile, the Alliance deployed, for the first time, rotational forces in the territories of the Eastern Allies – which also happen to be EU member states – strengthening deterrence and defence, as well as boosting the resilience of these states. The two organisations have also stepped up their assistance to Ukraine, each providing support in their respective areas of comparative advantage.

Similarly, the European Union and NATO have worked together to mitigate the challenges emanating from the South, by helping states in the region, such as Jordan or Tunisia, to ensure their stability. They have also sought to mitigate the effects of conflicts in neighbouring countries, such as Libya and Syria, including by addressing the effects of illegal migration, while protecting refugees.

In other words, cooperation between the European Union and NATO is not just what the two organisations do together but also what they do in parallel, coordinated and complementary ways. This is an important lesson for the future in view of EU ambitions to develop a common European defence in the long term. This effort – which may or may not materialise – should not be seen as a substitute to NATO but rather as a mutually reinforcing endeavour, which complements both organisations' tasks.

How did the institutional relationship evolve?

The relationship between the two organisations is all of the above – but it is also the interaction between them. This interaction is more recent, having started roughly twenty years ago at the NATO Washington Summit in 1999, and is constantly evolving. It can broadly be distinguished in three periods: first, the setting-up of the mechanisms for cooperation; second, a period of slow evolution; and lastly, one of renewed dynamism.

The institutional relationship evolved out of necessity. Since the Treaty of Maastricht in 1993, the European Union has had the ambition to develop a common defence policy that might lead to a common defence. This took a new dimension with the Treaty of Nice, signed in 2001, which allowed the creation of EU political-military structures.

The question was how to tie these developments with NATO. The answer was to set up a series of complicated arrangements between the European Union and the Alliance. The so-called “Berlin Plus” arrangements, agreed in 2003, provided the basis for the Alliance to support EU-led operations in which NATO as a whole is not engaged. This was a success in itself since it meant that, for the first time, the two organisations had developed concrete ways of working and communicating together.

However, these mechanisms became obsolete almost upon their inception. They were designed based on the experience and perceptions of previous decades, especially in the former Yugoslavia where the idea was that the European Union would follow NATO on the ground when it came to peace-support and stabilisation operations. In the words of the then NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, speaking in 2007: "NATO-EU relations have not really arrived in the 21st century yet. They are still stuck in the '90s." In the end, only two “Berlin Plus” operations were established: in 2003 in North Macedonia and in 2004 in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Another challenge was that both the European Union and the Alliance were transformed by big-bang enlargements that brought new members that were not all members of both organisations, which also led to different and occasionally diverging priorities within each organisation. The two organisations grew from 15 EU member states and 19 NATO Allies in 2003, to 28 and 29 respectively today.

The setting-up period was followed by a decade of slow evolution, during which nothing substantial happened and where cooperation between the two organisations was occasional, informal and below the radar screen. This period lasted roughly a decade from 2004 until 2014. During this time, both organisations acted and evolved, mostly in parallel and, occasionally, coordinated with each other.

At a time of unprecedented security challenges from the East and the South, President of the European Council Donald Tusk, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker sign a joint declaration on strengthening EU-NATO cooperation – Warsaw, 8 July 2016. © NATO

Things changed radically in 2014. Two developments led to the realisation that the status quo was untenable. First, as mentioned above, Europe was faced with new threats and challenges emanating from the East and the South – and neither organisation had the whole range of tools needed to address the changes security environment.

Second, the European Union laid the foundations for a common defence with the building of two defence pillars: the Permanent Structured Cooperation and the European Defence Fund. EU-NATO cooperation became the third pillar of European defence, underlining the organic link between the two organisations.

These events led to a radical shift in how the institutions work together. The Presidents of the European Council and the European Commission together with the NATO Secretary General signed two Joint Declarations in 2016 and 2018 setting out the principles of this renewed cooperation. Moreover, all NATO Allies and EU member states have endorsed a set of 74 common actions.

This in turn has led to a political, cultural and psychological turnaround. Nowadays, there is no NATO policy that does not have an EU dimension. Achieving this result was not easy, however, it has been well worth the effort. It has proved that taking EU-NATO relations forward is not a Sisyphean task – but it was, and still is, a Herculean task.