NATO has reached its 70th anniversary in much the same state that has marked virtually every year of its existence. To commentators and pundits on the outside, the Alliance seems to be in constant crisis and each new form of crisis is seen to be finally the terminal one. On the contrary, to those working on the inside, NATO has never seemed in more robust shape: engaged in more places than ever before, churning out initiatives at a faster pace than ever and in ever-longer Summit declarations. Now that the Alliance is firmly back in its most indispensable mission of collective defence, its future would seem to be more secure than in a long time.

The Alliance is refocusing on its core mission of collective defence. Pictured flag bearers representing Albania, Canada, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia and Spain mark the establishment of their new battlegroup in Latvia, on 19 June 2017. It is part of NATO’s enhanced forward presence, which aims to deter a resurgent and aggressive Russia. Photo: Corporal Colin Thompson, Imagery Technician, Joint Task Force – Europe.

This dichotomy will undoubtedly produce a debate that will be reminiscent of the ones that NATO experienced when it marked its 40th, 50th and 60th anniversaries. There will be those who play up the factors that divide, while others stress the factors that unite. Some will analyse the global strategic trends and argue that the Atlantic is becoming wider and that the days when Europe could rely on North America for its defence are over. Others will see the deteriorating international security situation and the rise of the illiberal authoritarians as reasons for the transatlantic partners to pull together, as they represent a diminishing slice of world population and economic power. Some will believe that NATO is the victim of history and of the strains pulling on multilateralism and the rules-based international order. Others will see in the Alliance a precious bulwark against these disruptive forces and a guarantee that the liberal democracies can still emerge the winners.

The daily picture of a NATO that is deploying new forces in its eastern member states, holding major exercises, combating cyber threats and terrorism, conducting training and capacity-building missions in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, and welcoming new members into its ranks will stand in baffling contrast to a political and academic rhetoric that presents NATO as obsolete and Allies as a drain on resources for little return. In short, the optimists will not see the need for the Alliance’s reform, while the pessimists will not deem it possible. As so often in the past, it will come down to a choice between actions and words, and what most determines NATO’s credibility in the long run. If the glass is equally half full and half empty, then both sides are right and we are no further forward.

Yet to repeat this somewhat sterile discussion on the occasion of NATO’s 70th anniversary would be a lost opportunity – perhaps even a historic mistake. Because to claim that all is well or not well with NATO is to distort reality and to miss the point.

Yes indeed, the Alliance is not faring so badly when we consider the criticisms and doubts affecting so many of the other institutional pillars of the post-war international order. Finding good news stories about NATO is not difficult, and the frustrations of the last two NATO summits belie an impressive record of concrete achievements. Taken together they show just how committed to NATO its 29 members still are – in cash, capabilities and troops as well as speeches.

But without lapsing into facile crisis constructs, we also need to face up to the fact that the Alliance is today operating in the most complicated security environment in its history. It is facing a more diverse spectrum of threats than ever before. Certainly, these may not be as existential as the threat of nuclear holocaust during the Cold War but they are nonetheless severe and, if not mastered, could end the liberal democratic societies and individual freedoms that the citizens of NATO countries today take for granted.

The 21st century is the century of turbulence with great power competition; rising military spending and readiness to threaten or use force; rapid and far-reaching technological innovation, which is putting greater disruptive and destructive capability into the hands of more bad actors; and hybrid campaigns to divide and destabilise western societies, and gain leverage over their political and economic systems. More than before, the Allies are being challenged from within and without their borders and from multiple directions at the same time. Death by a thousand cuts may not sound as bad as sudden death but the result is still the same.

Challenges on all fronts

For most of the past decades, NATO had the relative luxury of dealing with one challenge in one place at any given time. It marked its 40th anniversary focused entirely on the changes affecting the Soviet Union; its 50th anniversary was in the midst of the Kosovo air campaign; and its 60th anniversary was dominated by discussions over troop surges in Afghanistan. But this time it is different. NATO is reaching 70 when it has to tackle not one but three strategic fronts, not only diverse geographically but also in terms of the type of threats they pose and the responses they require.In the East, a resurgent and aggressive Russia has made NATO’s eastern Allies nervous and requires the Alliance, after a nearly 30-year gap, to be able to deter, defend against and defeat a peer adversary with modernised forces, abundant war-fighting experience and high-tech weaponry.

NATO is building the capacity of partners in its southern neighbourhood to tackle security challenges. Pictured US Admiral James Foggo, Commander of Joint Force Command Naples, talks with students at Iraq’s Explosive Ordnance Disposal School in Besmaya – 7 February 2018.

© NATO JFC Naples

Learn more about NATO in Iraq

In the South, fragile states are vulnerable to extremism, militias and criminal gangs, which pose a range of security headaches ranging from terrorist attacks to humanitarian crises and uncontrolled migration. These require local knowledge, development and long-term capacity-building partnerships with multiple actors.

On the home front, we see the polarisation of many western societies as they struggle to control the dependencies created by globalisation. Moreover, all-embracing technologies have given malicious actors a new hybrid toolkit to either wreak havoc or to assert influence.

These challenges affect Allies in different combinations and come from different sources. But all Allies expect NATO to be equally attentive to their individual concerns and to provide answers. What is unique, therefore, about the situation NATO finds itself in today is that it risks becoming unmanageable. One danger is strategic overload. Another is that poorly managed crises on the home front or a failure to establish deterrence against provocations such as cyber or chemical attacks, which fall below the threshold for Article 5 (NATO’s collective defence clause), could embolden adversaries to make territorial demands as well. Equally, allowing those adversaries to quash human rights and to sow corruption and poor governance in the South – all in the name of re-establishing “order” – could encourage them to try the same tactics in the Alliance’s eastern neighbourhood.

So, for the first time in its seven decades, NATO has to deter and defend against the enemy within as well as without. As we saw after the 9/11 terrorist attacks against the United States, from now on, Article 5 could well apply more to threats against transport, power infrastructure, space communications, pipelines, IT networks and civilians sitting on park benches than to tanks crossing borders. Solidarity will no longer be a rare requirement waiting for a military attack that is potentially catastrophic but extremely unlikely. Rather, it will be an almost daily necessity in response to provocations that are not existential but which civilised societies cannot allow to go unchallenged.

This is fundamentally new and the most pressing issue that Allied leaders need to debate, if they wish NATO to have a future at least as long as its past. Instead of preparing for one kind of attack, how does the Alliance make its member states (and some key partner countries too) fully resilient and able to respond effectively to the 21st century’s pattern of hyper-interference and ubiquitous competition?

In 2014, Allies made cyber defence a core part of collective defence, declaring that a cyber attack could lead to the invocation of the collective defence clause (Article 5) of NATO’s founding treaty. Photo courtesy wilsoncenter.org

This is not to imply that the topics which dominate NATO’s current political agenda are not important. Burden-sharing is at the centre of US President Donald Trump’s view of the utility of the Alliance to the United States and any future US Administration, whether Republican or Democrat, is likely to insist on it too. The speech given by Secretary of Defence Robert M. Gates in Brussels in 2011 came from a Democrat Administration and – in its sharpness and sense of urgency about European capability gaps –prefigured the Republican Trump half a decade before the latter entered the White House.

The United States’ share of the burden of collective defence or, more recently, non-Article 5 operations beyond NATO’s territory has always been disproportionate and unfair. Prolonged European dependence on the United States was one major reason why some US Senators wanted to limit the lifespan of the NATO Treaty to just ten years, when it came up for ratification in 1949. The Europeans have constantly promised to rectify the discrepancy through a host of burden-sharing and offset initiatives, and failed to do so. As Europe became richer and aspired to be treated as an equal actor on the global scene, its inability or unwillingness to provide for its own defence became ever more incomprehensible.

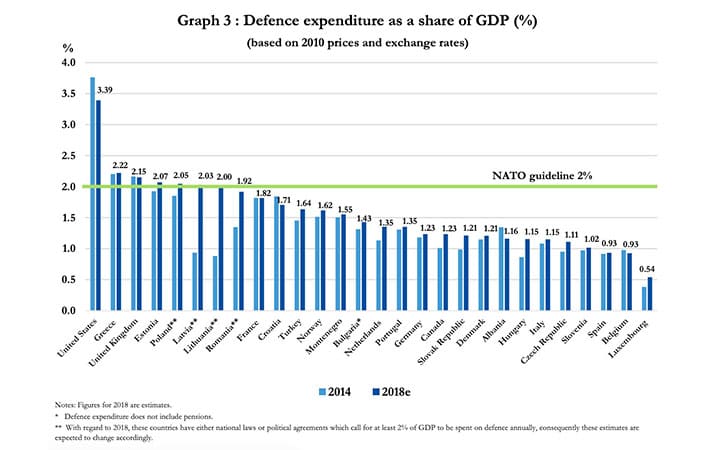

So, rather than resent the current return of the burden-sharing debate, Europeans should perhaps congratulate themselves on their good fortune that Canada and the United States have been willing to underwrite Europe’s defence in peacetime for longer than any of NATO’s founding fathers would have thought possible – or desirable. Simply put, Europeans need to increase their defence budgets to two per cent of GDP; not because the United States demands this as a precondition for sustaining NATO but because Europeans are living in an increasingly rough neighbourhood with multiple threats. In these circumstances, two per cent will give Europeans the capabilities required so that they do not need to make hard choices between deterring Russia or fighting extremists in the Sahel; or fielding high readiness divisions over developing more robust cyber defences and researching the emerging technology areas of artificial intelligence, robotics and hypersonic rockets.

Now that the Defence Investment Pledge, agreed at the 2014 NATO Summit in Wales, has halted the decline in defence spending and led to real increases, the Allies clearly have to maintain this effort. But they also need to develop a narrative that explains the link between money, capability and security. Headline figures can seem somewhat arbitrary. An extra 100 billion dollars by 2020 is a lot of money but NATO also needs to show the public what this means in terms of actual improvements in equipment, readiness and training, and focus more on the national success stories.

The Defence Investment Pledge, agreed in 2014, has halted the decline in defence spending and led to real increases. In 2018, seven Allies reached the two per cent defence spending guideline, up from three in 2014. © NATO

See defence expenditures of NATO countries 2011-2018

Capabilities that address threats such as cyber, military interference with vital space assets, terrorism, border security, data manipulation, the protection of critical infrastructure and crucial supply chains, and humanitarian crises engendered by extreme weather events may resonate more with the public than traditional hard military items such as tanks and artillery. This argues for NATO’s defence planners to take a broad view of capability requirements. The two per cent should be a target for the European Union as well as for NATO. Because if the United States were one day to turn its back on NATO or limit its engagement only to territorial collective defence vis-à-vis Russia, two per cent would be the minimum for European Strategic Autonomy to have any meaning. Consequently the Defence Investment Pledge needs to move progressively from an effort largely driven by the United States to one that Europeans demand of each other.

This said, the function of NATO is not primarily to be about fairness. Equal benefits for equal contributions. Outputs – the benefits gained from being an Ally – will always be more significant than inputs. What counts is that individual inputs maximise collective impact. The diversity of Allies (big and small, with different assets and networks of influence) means that they will always contribute in different ways.

The role of NATO must be to incentivise activity and find ways to combine different contributions for maximum strategic effect. This is more effective than formulating standardised contributions, which could make NATO too strong in certain domains and too weak in others. As NATO tackles 21st century challenges, a broad and diverse spectrum of different assets, skills, knowledge and capabilities will arguably be the Alliance’s comparative advantage over its adversaries. Russia with its largely military power and strategy based on intimidation is a case in point. But it will not be enough to acquire diverse assets –NATO’s challenge is to learn how to use them.

It is in this connection that I see four areas where the Alliance needs to raise its game.

Scanning the risk horizon

The first is the need for more discussion among Allies on the trends and events shaping the future of security.China, for instance, will have a massively greater impact on international relations in the 21st century than Russia – and in very different ways. It is already pulling ahead in the defining technologies of artificial intelligence and bioengineering as well as in 5G connectivity, which will drive the Internet of Things. It is increasing its investments in Africa, Europe and the Middle East, and sending more of its troops to United Nations peacekeeping operations. Already, as Allies discuss the wisdom of allowing Huawei into their future IT networks, they see that China could divide them while Russia generally tends to unite them.

NATO Deputy Secretary General Rose Gottemoeller participates in the Xiangshan Forum, during a session on Artificial Intelligence and the Conduct of Warfare, in Beijing, China – 25 October 2018. © NATO

As the Chinese model will be the main competitor to liberal democracy, a key question will be how the Allies handle the rise of China. It is not a question of seeing China as the next military threat but how best to understand it and engage it. Perhaps the time has come to create a NATO-China Council or at least a regular strategic dialogue. Past cooperation on countering piracy together in the Gulf of Aden or helping the United Nations and African Union with capacity building show the potential of NATO-China relations. For a starter, NATO should appoint a senior diplomat or official to focus on China and develop the network of contacts with the People’s Liberation Army and the civilian leadership.

Apart from China, other key issues need to be on the Alliance’s agenda more systematically. For instance, while NATO is developing a space policy, the Alliance still has not declared space as a domain or looked seriously at its growing dependency on space assets for navigation, timing, tracking and targeting. Yet 58 nations have now put satellites in orbit and most space-enabled services, which NATO is dependent upon, are dual use (civil/commercial and military). The growth of missile defence, hypersonic missiles, drones and data processing, not to mention early warning capabilities and cyber security, will make space ever more contested. Satellites will be more vulnerable to manipulation, disruption and destruction, and the outcome of conflict will increasingly depend on who makes best use of space. This is the reason why the United States has recently stood up a Space Force and is planning for a Space Command.

Other issues deserving more attention are Russia’s role and influence beyond Europe, especially in Africa and the Middle East, and the emerging role of actors such as India, Iran and Saudi Arabia. But it is not only traditional states with traditional capabilities that are transforming the nature of security. Equally important questions to address include: How will the decisions of big tech companies shape and control the future of the Internet and social interaction? How will ISIS/Daesh regroup and define a new business model post-Caliphate? Or how is organised crime undermining governance and fuelling corruption?

NATO cannot rely on infrequent ministerial meetings or occasional briefings from national diplomats passing through Brussels. A recent crisis like that between India and Pakistan in Kashmir shows just how quickly events can spin out of control and have global security implications. NATO needs to think how it can better align its situational awareness and consultation machinery with the fast-moving and unpredictable security environment. It cannot be perceived as an organisation dealing narrowly with a limited set of issues and only in its immediate neighbourhood.

Deterring hybrid threats

The second area where the Alliance needs to raise its game is deterrence against threats below the Article 5 threshold. Hybrid warfare is complex because the dividing line between legal and illegal activity is a fine one. Where do normal business transactions become hostile state interference? How can we prevent adversaries from using against us the technology we ourselves have invented? Some commentators have declared that deterrence cannot work against hybrid threats because they are multifaceted and simply exacerbate the polarisation and divisions that are already so prevalent in our societies.

Certainly, there is no easy and immediate fix to deterrence in the hybrid domain, such as the acquisition of a nuclear weapon to neutralise an opponent’s nuclear capability. Indeed, deterrence by denial or depriving the adversary of the fruits of aggression through resilience and speedy recovery is the starting point. Yet the response to the Russia-sponsored chemical attacks in Salisbury one year ago showed the range of other measures that can be taken. The perpetrators were named and shamed through the disclosure of intelligence material; there was a coordinated expulsion of a large number of Russian diplomats; NATO and the European Union pulled together and both organisations initiated a review of their preparedness and response assets against chemical and biological attacks.

The attack on ex-spy Skripal and his daughter in Salisbury, the United Kingdom, on 4 March 2018, was the first offensive use of a nerve agent on Alliance territory since NATO’s foundation. The Allies were united in expressing deep concern about this clear breach of international norms and agreements. © Reuters

In sum, deterrence can be gradually built up against hybrid campaigns by credible attribution of the source; naming and shaming; proportionate responses that do not escalate but show that hybrid attacks will be consistently answered and in a collective and united way. It is also essential to identify and plug vulnerabilities in NATO’s spectrum of critical infrastructure in both the physical and virtual domains. These responses will contain an element of trial and error, as the Alliance sees what works best in inducing an adversary to think again. They will also necessitate the development of a playbook of measures – both existing and new – and learning how to apply them in targeted ways, whether against states or the proxies they employ.

Crucially, NATO will need to develop a culture of permanent responsiveness, reliable intelligence and the ability to take lots of small decisions regularly and early, rather than big decisions rarely and late. But to the extent that NATO can operate more effectively at the sub-Article 5 level, it is less likely to have to face contingencies above that threshold in the future.

Rebuilding partnerships

The third area that the Alliance needs to pay more attention to is partnerships. One of NATO’s biggest success stories, since the end of the Cold War, has been to induce around 40 other countries to form structured partnerships with it. These have been based on mutual benefit. Partners have contributed troops to NATO-led operations, while having access to a multinational forum to exchange views and develop practical cooperation on shared security concerns. Partnering with Allies has made their own role in international security more substantive. Interoperability has been as much intellectual as military and practical. Partners have been attracted to the Atlantic Alliance as a community of democracies, while strengthening NATO’s legitimacy in the United Nations and the wider world. In short, a win-win outcome. But this is now in danger of being lost as the Alliance’s priorities shift and the focus swings back to collective defence.Bright hopes were once invested in the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council. Now, consultation is ad hoc and other partnership frameworks, such as the Mediterranean Dialogue or the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative, need re-energising and a greater sense of purpose. Beyond a limited number of individual partnerships, such as with Sweden and Finland, NATO has not articulated an overall vision for partnership. Yet, in a world where multilateralism is under threat, this network is a precious asset and needs to be revived before it atrophies.

At its height, the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (2003-2014) was more than 130,000 strong with troops from 50 NATO and partner nations. Partner support continues for the follow-on Resolute Support Mission. © NATO

One answer is to take up the debate on norms where partnership was acquiring a reasonable track record, for instance, in finding common ground on advancing the women, peace and security agenda, the role of private security companies, and the protection of civilians and combatting trafficking. The current security environment badly needs new norms on challenges like cyber, autonomous weapons systems, social media and GPS interference and space satellites, to name but a few. NATO is not necessarily the place where norms should be formally negotiated but it can be a useful forum for separating the good ideas from the bad, building consensus and convening the players, including non-governmental organisations and the private sector, around the same table.

At a time when so much of NATO’s image is bound up with ever higher defence budgets and more high-end military capabilities, rebuilding partnerships can help reassure our publics that the Alliance has a political and not exclusively military approach to security.

Encouraging European defence

Finally, the Alliance needs to get to grips with the issue of European defence. From the very beginning of NATO, a fault line has run through the Alliance as to whether it should encourage or discourage a specifically European (and now EU) defence identity.In the early 1950s, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles threatened the Europeans with “an agonising reappraisal” if they did not create more European (and especially German) divisions. The result was the European Defence Community (EDC), which failed in the French National Assembly in August 1954.

Over 60 years later, the debate on whether there should be a European Army or a European Strategic Autonomy continues unabated. Some want the greater European capabilities without the separate institutions; others, the institutions without worrying too much about the extra capabilities. At one moment, the case is made that a European defence construct is needed as a hedge against US disengagement. At another moment, it is seen as a way to strengthen the Alliance and the transatlantic partnership by overcoming the fragmentation of European defence budgets and procurement programmes, and producing more bang for the euro through more cooperative programmes.

For many decades, this effort has been stymied by the inconsistent attitude of the United States (do we support it and, if so, under what conditions?) and divisions among the Europeans themselves (can we develop a common culture when it comes to the use of force and how can this effort serve all of us, rather than the individual agendas of one or two key EU member states?).

But today we are at a critical juncture. The European Union has launched a series of initiatives that are the most far-reaching since the demise of the EDC and which put structures and resources behind the aspirations. We have Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) with 34 multinational projects; a European Defence Fund with an initial capitalisation of 13.5 billion euros; and a European Intervention Initiative to foster a common strategic culture on power projection and mission planning. French President Emmanuel Macron has proposed a European Security Council and the consolidation of the European Union’s defence and technology industrial base. Yet, we also have Brexit and the challenge of keeping the United Kingdom as a key Ally firmly embedded in European defence across the whole spectrum, from intelligence and police cooperation to combat brigades.

Attending the EU Defence Ministers meeting in Romania on 30 January 2019, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg declares “For NATO it’s a good thing that Europe, the European Union do more together when it comes to defence, because we believe that can develop new capabilities, increase defence spending and also address the fragmentation of the European defence industry.” © NATO

Consequently, the task for NATO is how to encourage but help steer these European initiatives. Of course, unnecessary duplication should be avoided. But the priority must be to relieve the pressure on the United States by enabling the Europeans to take on collective defence missions at the high end within the NATO framework; better support stabilisation in Africa and the Middle East; define the scope of EU solidarity in responding to events like cyber and terrorist attacks or natural disasters (articles 42.7 and 222 of the Lisbon Treaty); and spend defence euros to greater effect through the integration of effort and more investments in cutting-edge technology.

Essentially, NATO will need to hammer out a new transatlantic bargain: one in which the United States accepts the reality of EU defence integration and ceases to see it as a competitor or threat to NATO; and one in which the EU countries deliver on their capability promises and pursue their efforts in a way that strengthens NATO’s overall capacity to address the challenges to the East and South as well as hybrid threats. For this, the European Union will need to be generous towards the non-EU Allies on the basis of close association in return for significant contributions to these efforts. EU defence aspirations will not go away but neither will NATO. It is the task of this generation of political leaders to finally bring them together.

The 70th anniversary of the Alliance will produce plenty of pieces on NATO’s past achievements and many messages of esteem and commitment. That is all to the good. Yet, the anniversary is also the opportunity for some political recalibration that can make the Alliance successful for the next seven decades. It is an opportunity that should not be missed.