The current unpredictable security environment has led to a renewed focus on civil preparedness. NATO and its member states must be ready for a wide range of contingencies, which could severely impact societies and critical infrastructure.

Since the early 1950s, NATO has had an important role in supporting and promoting civil preparedness among Allies. Indeed, the principle of resilience is set out in Article 3 of the Alliance’s founding treaty, which requires all Allies to “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack”. This involves supporting continuity of government, and the provision of essential services in member states and civil support to the military.

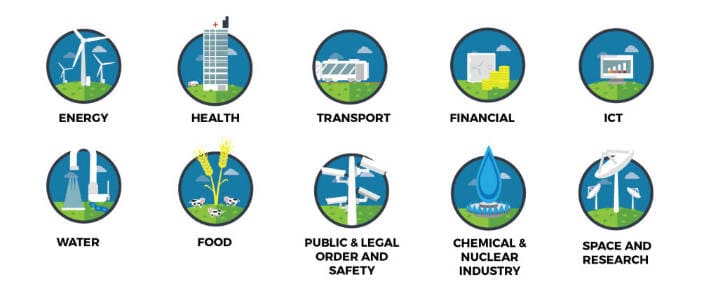

Modern societies are highly complex with integrated and interdependent sectors and vital services. This makes them vulnerable to major disruption in the case of a terrorist or hybrid attack on critical infrastructure. © EU

Through much of the Cold War era, civil preparedness (then known as civil emergency planning) was well organised and resourced by Allies, and was reflected in NATO’s organisation and command structure. During the 1990s, however, much of the detailed civil preparedness planning, structures and capabilities were substantially reduced, both at national level and at NATO.

Events since 2014 – most notably Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and the rise of ISIS/Daesh – signalled a change in the strategic environment, prompting the Alliance to strengthen its deterrence and defence posture. Meanwhile, terrorist and hybrid threats (particularly recent cyber attacks) continue to target the civil population and critical infrastructures, owned largely by the private sector. These developments had a profound effect, bringing into sharp focus the need to boost resilience through civil preparedness. Today, Allies are pursuing a step-by-step approach to this end – an effort that complements NATO’s military modernisation and its overall deterrence and defence posture.

NATO’s baseline requirements

In 2016, at the Warsaw Summit, Allied leaders committed to enhancing resilience by striving to achieve seven baseline requirements for civil preparedness:

1) assured continuity of government and critical government services;

2) resilient energy supplies;

3) ability to deal effectively with uncontrolled movement of people;

4) resilient food and water resources;

5) ability to deal with mass casualties;

6) resilient civil communications systems;

7) resilient civil transportation systems.

This commitment is based on the recognition that the strategic environment has changed, and that the resilience of civil structures, resources and services is the first line of defence for today’s modern societies.

More resilient countries – where the whole of government as well as the public and private sectors are involved in civil preparedness planning – have fewer vulnerabilities that can otherwise be used as leverage or be targeted by adversaries. Resilience is therefore an important aspect of deterrence by denial: persuading an adversary not to attack by convincing it that an attack will not achieve its intended objectives.

Resilient societies also have a greater propensity to bounce back after crises: they tend to recover more rapidly and are able to return to pre-crisis functional levels with greater ease than less resilient societies. This makes continuity of government and essential services to the population more durable. Similarly, it enhances the ability for the civil sector to support a NATO military operation, including the capacity to rapidly reinforce an Ally.

Such resilience is of benefit across the spectrum of threats, from countering or responding to a terrorist attack to potential collective defence scenarios. Consequently, enhancing resilience though civil preparedness plays an important role in strengthening the Alliance’s deterrence and defence posture.

NATO engages several partners in its efforts to enhance resilience, as one element of cooperation that contributes to stability and security for the Alliance. Finland and Sweden, for example, have helped shape this area of NATO’s work by actively sharing their national best practices with Allies.

In December 2018, NATO Allies and partners helped Albania to cope with the most severe rainfalls ever recorded in the country, following a request for assistance via NATO’s Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre. © NATO

NATO’s focus on resilience has shifted the emphasis of its work on civil preparedness with Allies and partners to so-called “left of bang” requirements (building situational awareness and readiness prior to potential incidents or attacks). But NATO maintains the capacity to respond to major civil emergencies. In the event of an earthquake, raging forest fires or massive flooding, for example, or a disaster caused by human activity, NATO’s principal civil emergency response mechanism, the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre can, upon request, coordinate assistance to a stricken Ally or partner country.

The risks and vulnerabilities of modern society

Modern societies are highly complex with integrated and interdependent sectors and vital services. They rely on supporting critical infrastructure to function, but take for granted that it can withstand disruption. Moreover, the supply of goods and services is determined almost exclusively by market forces, largely working according to the “just in time” delivery model. Internet-based communications systems and logistics are also fundamental to the production, trade and delivery of goods and services.

Such a high level of interconnectedness is more efficient and allows for economies of scale. But greater interdependencies also increase the risk of cascading effects in the event of a disruption (Marc Elsberg’s disaster thriller “Blackout” provides a good illustration of the potential impact of a disruption to electricity and power systems).

National authorities have legislative and regulatory powers but little few direct controls to influence or steer supply in the private/commercial sector, other than in an emergency situation. As the system seems to work efficiently, there has been little incentive for national authorities to engage directly. Instead, it has been left mainly to industry to resolve any supply shortfalls. For government, the focus has been on ensuring safety and quality levels of goods and services, particularly of food and other consumables.

The European Union (EU) plays a very strong role in the public administration architecture for these sectors. EU directives and regulation have substantially shaped the planning by its member states, as well as by the commercial sector. Contingency planning, which seeks to ensure the functioning and maintenance of operations, has focused predominantly on the ability to deal with the most probable disruptive incidents in the short term. The commercial sector has mainly focused on minimising their own costs given such a disruption, rather than preparing for larger-scale contingencies with cascading effects across sectors and society itself.

Until recently, security and defence concerns – seeking to ensure the physical security of supply and physical protection of infrastructure in crisis – have not been prominent issues. Emergency legislation enables national authorities to assume control over sectors and resources, including capabilities and infrastructure. However, the necessary mechanisms and procedures are designed mainly for extreme situations, such as war, and not for the grey area that would accompany an escalating geopolitical crisis short of outright armed conflict.

A major disruption to electricity and power systems could potentially have a catastrophic impact on the functioning of society.

© Federal Ministry of Education and Research / Germany

Few Allies have tested the functioning of these mechanisms and procedures recently to ensure they will stand the test of shock or surprise. The degree and impact of foreign direct investment in strategic sectors – such as airports, sea ports, energy production and distribution, or telecoms – in some Allied nations raises questions about whether access and control over such infrastructure can be maintained, particularly in crisis when it would be required to support the military. This issue requires further attention.

While civil preparedness is primarily a national responsibility, it is an important aspect of NATO’s security. Indeed, strengthening national resilience provides a better foundation for collective defence. NATO’s approach to building resilience is through an “all-hazards” approach: planning and preparedness that is relevant for all types of threats, whether it be natural disastershazards, hybrid warfare challenges, terrorism, armed conflict, or anything in between. National authorities have realised that the risks and vulnerabilities they face, amplified by the level of interdependence among the sectors, requires a whole-of-government effort as well as more direct cooperation with the private sector.

NATO’s civil preparedness has facilitated and supported national efforts, developing sector-specific guidance and tools to assist national authorities in their effort to meet the ambition established by the seven baseline requirements. These include guidance on a range of issues, including how to deal with the movement of tens to hundreds of thousands of people; addressing cyber risks to the health sector; comprehensive planning for incidents involving mass casualties; and ensuring security of medical supply arrangements. NATO’s civil experts, who are based in Allied nations, have helped assess and provided tailored advice on measures to enhance resilience and levels of civil preparedness.

Ensuring coherence of effort

With the changed security environment, NATO’s defence planning efforts have been reinforced, including in the area of civil preparedness. NATO’s seven baseline requirements include a systematic approach to improving these capabilities. Regular assessments are an essential aspect, helping to identify and measure areas of progress and challenges. The findings, based on data provided by Allies, help to inform the direction for further national or collective action. The assessments cover both an aggregate report on the State of Civil Preparedness and, as part of the individual country reports, the state of civil preparedness of a given Ally.

Once again, civil preparedness is the subject of more active engagement with capitals and civil ministries in a collaborative effort to assess and advise on improvements. An initial assessment in 2016 was followed by a report in 2018, which identified several shortfall areas, where further resources and effort to support national authorities are needed.

These assessments allow the testing of assumptions about the availability of resources, the levels of preparedness and protection of civil resources and infrastructure, including those that support the military. They help ensure coherence between NATO’s efforts on resilience through civil preparedness with those on the military side. Over the longer term, they aim to promote greater civil-military cooperation in member states. This will require a more persistent effort to rebuild the structures, relationships and plans that facilitate civil-military cooperation contributing to NATO’s adapted deterrence and defence posture.

What’s next?

Since 2014, NATO has made significant achievements in giving substance to the concept of resilience through its civil preparedness efforts. Building on the seven baseline requirements, the commitment by Allies and the detailed planning guidance, regular assessments have provided a greater understanding of areas of progress, as well as remaining challenges.

As NATO develops its third report on the State of Civil Preparedness for 2020, there is scope to further refine the baseline requirements, including in ways that make progress more measurable. This would make it easier to compare civil preparedness across the Alliance and track national progress over time. Several nations have already taken steps in this direction and existing research to measure levels of resilience, for example that of critical infrastructure, should inform NATO’s efforts on civil preparedness.

During NATO Exercise Trident Juncture 2018, Norway involved its civilian emergency response agencies to exercise and validate aspects of its approach to resilience. © NATO

Sufficient flexibility is required to allow this capability development approach to suit the needs of a diverse Alliance of 29 nations, which retain the primary responsibility over their civil preparedness. At the same time, given the unpredictable nature of the security environment, Allies will be called upon to ensure that their national resilience bolsters NATO’s collective defence and security objectives.

One of the most important means available to address these imperatives is training and exercises, whether from a national, multinational or Alliance perspective. Trident Juncture 2018 – NATO’s most important military exercise since the end of the Cold War – enabled Norway to exercise and validate aspects of its approach to resilience within its Total Defence concept. This exercise also provided other Allies with a good example of how more comprehensive and joint (civil/military) exercises can help prepare them for the full range of potential contingencies that they could face in light of the strategic environment.