Enabled by corruption, illicit trade poses manifold challenges to security across the world. Global responses are needed urgently.

Corruption and illicit trade are at the root of instability in many parts of the world, such as in Syria and Iraq, in intractable conflicts in Africa, or in the increasingly difficult to inhabit megacities of the world. But the impact of illicit trade and pernicious and pervasive corruption affects us all: undermining the fabric of our societies, depleting the planet’s limited resources and contributing to the extinction of endangered species. Corruption has helped illicit trade expand both in the real and the virtual world, making the products and services of the illicit economy more widely available. The purchasers of these illegal commodities include all of us who are buying fish that should not be caught, wood products from protected forests, and computers and cell phones whose essential components are obtained through the efforts of trafficked labourers. Addressing this harmful corruption and illicit trade needs to be a much higher priority for world order.

The corrosive impact on Syria

The conflict in Syria brings into focus both the long-term corrosive impact of corruption and illicit trade. This deadly crisis, in which an estimated 475,000 have been killed and 14 million have been wounded and displaced began not just with the Arab Spring and the rise of a population against an authoritarian leader. Rather, there was another important source of this instability.

Sheikh Ghazi Rashad Hrimis touches dried earth in the parched region of Raqqa province in eastern Syria, where lack of rain and mismanagement of the land and water resources have forced up to half of a million people to flee the region – November 2010 © Reuters

A mass exodus of five million from rural areas occurred, in part, as a result of recurring drought and the decline of the famed Fertile Crescent of the Middle East. But it was not just climate change that made Syria one of the most urbanised countries in the world between 2002 and 2010. In the 1970’s, the father of the current Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad, launched an ill-conceived drive for agricultural self-sufficiency. As water became less available, people dug deeper wells in search of even less accessible supplies. In 2005, to deal with the paucity of water, President Bashar al-Assad made it illegal to dig new wells without a license that required the payment of a fee.

In an environment with high levels of corruption, the digging did not stop, as those that had money for bribes could dig deeper. There was an illicit trade in water rights, aggravated by corruption. But even with money, the relief was not sustained. The drought in the once-fabled Fertile Crescent continued – probably impacted by climate change – and any remaining water was at such depth that it was no longer profitable to dig.

Recent migrants to urban areas fleeing drought-affected areas congregated in the illegal settlements that developed on the periphery of Syrian cities. There the consequences of poor governance contributed to the insecurity of the recent migrants. These newly populated communities, neglected by the corrupt Assad government, were characterised by a paucity of infrastructure, high crime rates, absence of services, unemployment and ultimately “became the heart of the developing unrest” during the Arab Spring.

The story of the Syrian drought refugees does not end with the beginning of the Arab Spring. Rather, it is the beginning of a “domino effect.” The Syrians departure from rural areas was the first phase of a longer trajectory that often took a more tragic course, as the internal migrants then fled civil war and destruction. Many left for Europe, via precarious smuggling routes and embarking on flimsy boats that traversed the tumultuous seas of the Mediterranean.

A whole illicit industry, facilitated by corrupt officials, now exists to facilitate the movement or “trade” in people. Individuals sell their remaining valuables to pay the smugglers who can move their families to safety. Others pay part of the fee in advance, and then become indebted to the smugglers on arrival, becoming victims of human trafficking, often forced into work in slave-like conditions in Europe. Moreover, the mass movement of desperate migrants to adjoining states and Europe has created major political and economic crises in the destination countries that were not equipped to accept millions of displaced people.

Migrants from Syria warm themselves by fire at a makeshift camp near the village of Idomeni, Greece – March 2016. © Reuters

The Arab Spring started with hope and deteriorated into a prolonged conflict, with great human suffering, and massive loss of life and infrastructure. The Syrian conflict, like many others in the world, has been financed, in part, by illicit trade. This illegal cross-border trade is dependent on corrupt officials. Smuggling of drugs, humans, oil, antiquities, cigarettes and other contraband has provided funds to buy weapons and sustain fighters both of President Bashar Al-Assad and of rebel and terrorist groups.

Contemporary illicit trade in Syria today, in which many diverse elements of illegal commerce converge, helps facilitate many destabilising phenomena – the perpetuation of deadly conflict, mass human displacement and the propagation of environmental degradation. Those profiting from the smuggling in Syria include corrupt government officials, criminals and terrorists such as Al-Nusra and so-called Islamic State. Through their corruption, state actors undermine the state from within. Illicit trade today, when executed by non-state actors who do not need the state or seek to destroy the state, ensures the destruction of the existing order and of human life. The Syrian situation exemplifies illicit trade and its enabler – corruption – at its worst in the contemporary world.

Illicit trade on steroids

In the last three decades, traditional forms of illicit trade have not been eliminated but the newest forms of illegal commerce operate as if on steroids. Tied to computers and social media, they are fueling the exponential growth of many of the most dangerous forms of illicit trade: the massive sales of narcotics and child pornography online, and the escalation of sex trafficking through web and social-media based advertisements for which revenues now total in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

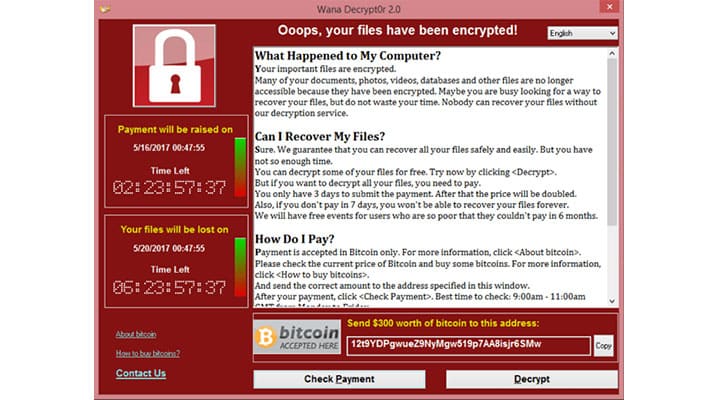

In the cyber world – particularly its most hidden part, the Dark Web – trade is based exclusively on impersonal and often anonymised relationships. Payments no longer are backed by states and their currencies, as customers pay for their purchases in a plethora of new cyber currencies of which bitcoin is the most known. Moreover, in this illicit world, the very commodities have changed and many can no longer be touched or exchanged through human hands. Rather many of the most pernicious illicit traders buy commodities only based on algorithms such as malware, Trojans, botnets, ransomware, and spam, marketed by malicious suppliers in both the developing and developed world. These virtual products are capable of doing great harm to ordinary citizens – stealing their identities, passwords and the money out of their bank accounts. The losses tied to these intangible goods now totals vast sums. Losses to ransomware alone are estimated to total five billion US dollars in 2017.

In May 2017, the WannaCry ransomware attack targeted computers worldwide that were running the Microsoft Windows operating system, encrypting data and demanding ransom payments in the bitcoin cryptocurrency. © Wikipedia

The changes brought by technology are most evident in the G7 countries – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States – the largest economies in the world, but one recent case of cybercrime had victims in 189 countries. Illicit trade in cyberspace also facilitated the hijacking of the European carbon markets, costing member states of the European Union, five billion euros. This crime attacked a mitigation strategy sought to address climate change and carbon emissions. Committed by ordinary criminals, corrupt bankers, terrorists and corporate facilitators, this large-scale crime reveals one of the greatest of coming challenges: the threat of an inadequately regulated cyber world to our planetary survival.

Illicit trade on steroids is not confined to cyberspace. Outside of the cyber arena, the greatest rates of growth in illicit trade are in different environmental crimes. In this time of diminishing resources on Earth with a continually expanding global population, there are ever-greater demands on the resources needed for survival. Illicit actors as well as corrupt state officials capitalise on the limited resources of the planet and exploit consumer demand for products that are made from endangered species such as rhino horn, ivory tusks or protected trees.

In a world in which demand increases price and shortages often contribute to the growth of illegal and black markets, illicit trade is resulting in the massive depletion of natural resources and wildlife. The world is observing an ever-expanding trade in fish that should not be caught off the coast of West Africa and species that should not be poached for personal consumption. Behind this trade are often corrupt officials, who use their positions to amass great personal wealth. In fact, the illicit trade in diverse species, is contributing significantly to the world’s sixth great extinction. We now face dysfunctional selection rather than the processes of natural selection that Darwin identified and guided life for tens if not hundreds of millions of years.

The world is at stake

Illicit trade exists for diverse reasons but widespread corruption at all levels lies at its core. Its varied causes means there is not one solution – an exclusively law enforcement, legal or military response is not sufficient. At present, illicit trade is targeting the very resources that we need to sustain life on the planet. Can we change its present trajectory? The vast majority of the world’s countries signed the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, agreeing to controls that would limit carbon emissions and thereby restrict the extent of climate change. Is the global community also ready to work together to address the threats posed by illicit trade and corruption, and the factors that are contributing to their growth?

Conservation officials burn 2.5 tonnes of seized ivory and rhino horn in Maputo, Mozambique, as part of a campaign to end an illicit trade that is fuelling a wave of big animal poaching in Africa – 6 July 2016. © Reuters

Such change requires more than modifying regulations on trade, but also controlling the world’s population and the demands that its inhabitants make on the planet. It requires a rethinking of the financial system to provide more transparency, a restructuring of the corporate world to focus on accountability, and strong anti-corruption measures to combat the facilitators of illicit trade. We need to find ways to control pernicious non-state actors, who have been major beneficiaries of globalised trade. Are there areas of illicit trade that we should decriminalise, or regulate less, to concentrate on the most severe threats to the global community?

Much of the new technology has been developed, and is owned and maintained by, the private sector. Therefore, the regulation of cyberspace is not exclusively in the hands of government, but often requires the cooperation of the private sector, which is inherently more interested in profit than in governance. This conflict of interest makes the reduction of illicit trade more difficult to achieve, unless fruitful public-private partnerships prevail.

The new security challenges are great and the windows of opportunity to reverse the planet’s present dangerous trajectory are limited. Addressing the complex sources of illicit trade requires better public policy and better understanding of the limits to growth, the impact of climate change and corruption, and the consequences of increasing economic disparity within and among countries.