Launched in February 2015, the Centre for Women, Peace and Security at the London School of Economics, developed out of the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative championed by former UK Foreign Minister William Hague and the Special Envoy for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Angelina Jolie. However, the Centre is not solely focused on the issue of sexual violence but on the wider agenda for Women, Peace and Security set out in United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, adopted in 2000. This Resolution brings issues relating to women and armed conflict directly into the political agenda of the Security Council, which has primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security. An important objective of the LSE Centre is to be a hub of cross-sectoral partnerships and engagements, to support the policy agenda through academic thinking, research and education.

Actress and Special Envoy of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Angelina Jolie, and the then British Foreign Secretary William Hague speak at a global summit to end sexual violence in conflict, in London (10 June 2014). © REUTERS

Resolution 1325 was widely celebrated by women’s non-governmental organisations, which had advocated globally for its adoption. It was the first time that the Security Council had devoted a full session to debating women’s experiences during and after conflict, and drawn attention to what have been termed the ‘inextricable links between gender equality and international peace and security’ (‘High-level Review on Women, Peace and Security: 15 years of Security Council resolution 1325’). It has been supplemented by further resolutions: 1820 (2008), 1888 and 1889 (2009), 1960 (2010), 2106 and 2122 (2013) and 2242 (2015).

The four pillars

These Resolutions build on each other and underpin what are often termed the ‘four pillars’ of the Women, Peace and Security agenda set out in Resolution 1325:

- Participation – Full and equal participation and representation at all levels of decision-making, including peace talks and negotiations, electoral processes (both candidates and voters), UN positions, and the broader social-political sphere.

- Conflict prevention – Incorporation of a gender perspective and the participation of women in preventing the emergence, spread, and re-emergence of violent conflict as well as addressing root causes including the need for disarmament. Addressing the continuum of violence and adopting a holistic perspective of peace based on equality, human rights and human security for all, including the most marginalised, applied both domestically and internationally.

- Protection – Specific protection of the rights and needs of women and girls in conflict and post-conflict settings, including reporting and prosecution of sexual and gender-based violence; domestic implementation of regional and international laws and conventions.

- Relief and recovery – Access to health services and trauma counselling, including for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

The four pillars are therefore an essential subject of contemporary foreign and military policy.

War and conflict have a disproportionate effect on women and children and yet historically women have been left out of peace processes and stabilisation efforts.

There has been some shift in emphasis in the Resolutions between the two key pillars on participation and protection. The pillar on participation and representation, especially emphasised at the outset of Resolution 1325 itself, presents women as agents, as active players in issues of peace and security. It stresses the importance of their ‘equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security’.

Protection

In contrast, the pillar on protection focuses on women as victims who need to be protected, especially from sexual violence as a tactic of war. Resolution 1820 gives greater prominence to this pillar, setting out a number of demands on all parties to conflict to take measures to enhance such protection including:

- enforcing appropriate military disciplinary measures;

- upholding the principle of command responsibility;

- training troops on the categorical prohibition of all forms of sexual violence against civilians;

- debunking myths that fuel sexual violence;

- vetting armed and security forces to take into account past actions of sexual violence; and

evacuation of women and children under imminent threat of sexual violence to safety.

Both the Women, Peace and Security agenda and the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative give some effect to the recognition of conflict as gendered – understood and experienced by women and men differently because of their gender. Both recognise how the incidence of sexual violence in armed conflict undermines international peace and security through its contribution to the displacement of peoples and refugee flows, and without steps to address it post-conflict, through its continuing divisiveness on communities and society. Accordingly both initiatives emphasise the importance of making accountable and prosecuting perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes (including such crimes involving gender-based and sexual and other violence against women and girls) to put an end to the impunity so often enjoyed by such persons.

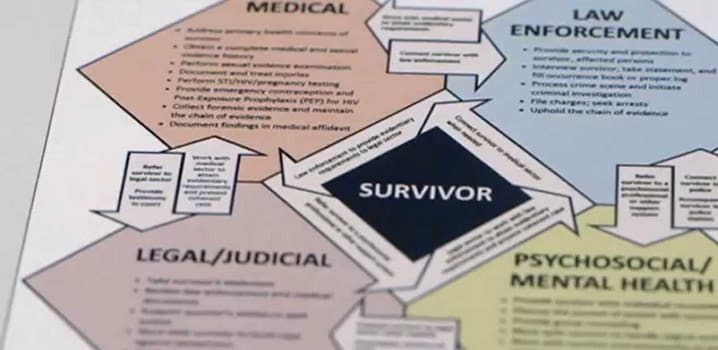

Adoption of the International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict is a core output of the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative. © YouTube

However, the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative is explicitly a gender neutral initiative. Its focus on prevention of and tackling impunity for conflict-related sexual violence is with respect to all victims, women and girls, men and boys, and those targeted for their (real or perceived) sexual or gender identity. But only one of the Women, Peace and Security Resolutions refers to the reality that such violence also affects men and boys as well as ‘those secondarily traumatized as forced witnesses of sexual violence against family members’ (Resolution 2106).

As an important output of the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative, an International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict was adopted to increase effective criminal prosecutions, both to enhance deterrence and to deliver justice in individual cases. This is a practical tool kit setting out good practice in response to the reality that criminal trials of perpetrators of sexual violence are seriously impeded by the lack of evidence appropriate for use in criminal processes and, moreover, that any trial may only be possible long after the commission of the offences by which time evidence may have been lost or become unusable. The Protocol has been tried in some pilot areas, gaps and other deficiencies identified, and a second edition has recently been completed.

Participation and representation

The Women, Peace and Security agenda has also given rise to institutional innovation, especially with respect to representation and participation. One example is the nomination of gender advisers in military forces and women protection officers in peacekeeping operations to support commanders in ensuring that a gender perspective is integrated into all aspects of an operation.

A Swedish female liaison officer serves as part of a military observer team, deployed under the NATO-led, UN-mandated International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. ISAF ended its mission in December 2014. (photo courtesy of the Swedish MoD)

The appointments of the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict (following the adoption in 2009 of Resolution 1888) as well as a Special Representative to the NATO Secretary General on Women, Peace and Security in 2012 are further external indications of the significance accorded to issues related to women and conflict.

In 2015, the Security Council welcomed efforts to increase the numbers of women in militaries and police in UN peacekeeping operations and urged further efforts in this regard (Resolution 2242). This of course assumes the importance of women within armed forces, an approach that NATO has long fostered with its formation in 1976 of the Committee on Women in NATO Forces (now the NATO Committee on Gender Perspectives).

A Global Study (‘Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace’) – commissioned to inform the discussions of the UN High-level Review of the implementation of Resolution 1325, fifteen years after its adoption – pushes for greater participation of women in peace processes to increase the chances of producing sustainable peace or stable post-conflict societies. It notes that ‘more than half of peace processes that reach an outcome lapse back into conflict within the first five years.’

Arguments for the inclusion of greater numbers of women in peace processes and post-conflict state-building (as well as in peacekeeping operations) have tended to rest on one of two grounds: that women ‘are good at peace’, are in some sense instinctively able to foster peace, or that this is required by general principles of equality and specifically by the 1979 Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination, articles 7 and 8. Neither of these arguments necessarily carries much weight. The first, an essentialist concept of biological determinism, is strongly contested as having no empirical basis while the second, the equality argument, is too often disregarded as having no practical benefit.

The Government of the Philippines and Moro Islamic Liberation Front signed a peace agreement in March 2014 after 17 years of negotiations, by which time one third of the people at the table were women. Women’s inclusion in peace-building creates a greater chance of agreement being reached and of that agreement lasting.

Recent research has made the case in strong instrumental terms that highlight the illogicality of premising the possibilities of peace on a narrow base that reinforces the pre-conflict power structures and fails to take into account the widest possible range of views, capabilities and lived knowledge of those who endured the conflict. The Global Study cites evidence-based research to the effect that in 40 peace processes adopted since the end of the Cold War there was not one single case where organised women’s groups had a negative effect on the process, which was not the case for other social actors. Specifically, women’s inclusion in peace-making creates a greater chance of agreement being reached and of that agreement lasting. Other research has shown that, when controlling for other variables, peace processes that included women as witnesses, signatories, mediators, and/or negotiators demonstrated a 20% increase in the probability of a peace agreement lasting at least two years. The percentage increases over time. A substantive gender perspective is also more likely where women have been involved.

The Global Study refers to the peace agreement reached between the Government of the Philippines and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MLF) in March 2014 after many years of conflict in Mindinao and 17 years of negotiations, by which time one third of the people at the table were women. The Agreement has strong provisions on women’s rights with eight out of its 16 articles providing for women in positions of governance and protection against violence. It also sets out special economic programmes for decommissioned female fighters from the MLF – a category of women often overlooked in programmes for disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration or for protection against violence. Nevertheless, and despite some slow progress, such instances are rare and women remain greatly under-represented in peace-making and peace-building.

Identifying gaps and addressing challenges

The Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative and the Global Study on Resolution 1325 have both identified gaps that remain to be filled. The latter also highlighted emerging trends and priorities for action. It asserted that ‘Resolution 1325 was conceived of and lobbied for as a human rights resolution that would promote the rights of women in conflict situations.’ As such, Women, Peace and Security is a human rights agenda for the enhancement of women’s human rights, elimination of discrimination on the basis of sex and gender and promotion of women’s empowerment. However, it is located within the security framework of the UN Security Council. The two dimensions – human rights and security – may be in tension giving rise to the warning in the Global Study that ‘attempts to “securitize” issues and to use women as instruments in military strategy must be consistently discouraged.’

Ambassador Marriët Schuurman of the Netherlands serves as the current Special Representative to the NATO Secretary General on all aspects of NATO’s contributions to the Women, Peace and Security agenda. © NATO

As indicated, much research on Women, Peace and Security has been carried out but more knowledge is needed. The LSE Centre seeks to become a world-leading education provider and a research forum that brings together scholars, activists, UN experts, practitioners and policy-makers. We need to shift rhetoric to practice by asking and exploring further questions, for instance, about:

- how patterns of sexual and gender-based violence relate to different forms of contemporary conflict and how different responses are needed – one size does not fit all victims and survivors;

- the connections between the political economy and violence in conflict and post-conflict;

- how to change social attitudes that allow perpetrators to continue their lives with impunity while survivors live with stigma, isolation and poverty throughout their lives;

- what capacity building is needed in different contexts to develop effective programmes for combatting violence against women in conflict; and

- how National Action Plans on Women, Peace and Security (and those of organisations, such as the plan for the implementation of Resolution 1325 developed by NATO together with partner countries in 2010) can be made more inclusive, more effective and adequately resourced.

The Centre aims to take advantage of its position as an academic research body with direct links to government, the military, international governmental and non-governmental institutions to contribute to the intellectual development of conceptual foundations and practical tools. It is envisaged that its normative input – with an emphasis on peace, justice and women’s human rights – will contribute to reshaping and enriching the discourse on issues related to women and conflict. In this way, it will help secure more effectively the transformative ambitions of the United Nations Women, Peace and Security agenda.