Deterrence is a relatively simple idea: one actor persuades another actor – a would-be aggressor – that an aggression would incur a cost, possibly in the form of unacceptable damage, which would far outweigh any potential gain, material or political. The involvement of at least two actors makes deterrence a complicated social interaction. It is very much about human nature, psychology and basic human emotions: fear, courage, trust, lust for power, and revenge.

Elevate all this to the level of state actors, with all the intricacies inherent in statehood and statesmanship, add the stakes of national survival, add nuclear weapons to the mix, and deterrence becomes a highly complex, volatile, intangible, but also combustible concept.

From deterrence by denial to denial of deterrence – and back

During the Cold War, NATO pursued deterrence by punishment and deterrence by denial. Deterrence by punishment was based on the notion of ‘unactable damages’, including through massive nuclear retaliation for any Soviet attack – conventional or nuclear. Deterrence by denial was about making it physically difficult for the aggressor to achieve his objective, which NATO pursued through forward defence at its eastern border with the Soviet Union.

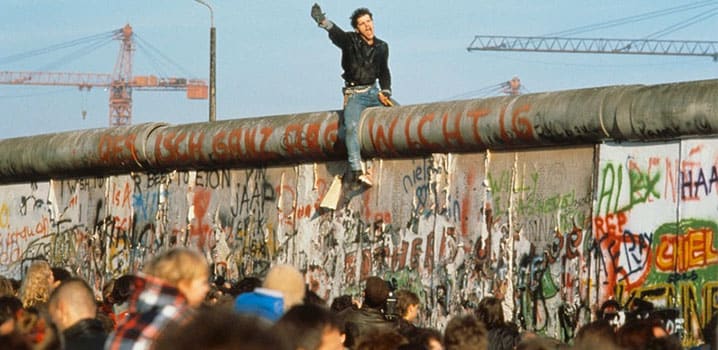

After the end of the Cold War, the Alliance dramatically downsized its conventional and nuclear forces.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, a long period of denial of deterrence followed. The Alliance dramatically downsized its forces (conventional and nuclear) and persistently reduced defence spending. It also shifted its overall paradigm from territorial defence, including forward defence conducted by large and heavy formations, to out-of-area crisis response, underpinned by expeditionary capability based around more deployable but also smaller and lighter units.

Along the way, the Alliance’s know-how of deterrence, including planning, exercises, messaging and decision-making has not been at the centre of NATO’s attention. And for good reason: the post-Cold War security environment demanded such a change in focus. The Alliance had to focus on crisis management – from conflict prevention, to peace enforcement, peacekeeping and stabilization – first in the western Balkans and later also in Afghanistan.

Today, deterrence is back. A good indicator is to compare the number of times the word ‘deterrence’ occurs in the respective communiqués of the 1999 Washington Summit (precisely once) and the 2016 Warsaw Summit (28 times). It was one of two interrelated themes in Warsaw: first, strengthened deterrence and defence for protection of the Alliance’s citizens; second, from this position of strength, projecting stability beyond Alliance borders.

The year 2014 was a turning point due to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the change of borders in Europe by force, and the rise of so-called Islamic State (or Daesh) in Syria and Iraq.

In the post-Cold War security environment NATO soon found itself having to focus on crisis management in the Balkans.

As an initial response, NATO took steps to boost its political and military responsiveness, and to increase the readiness of its forces. As part of the Readiness Action Plan (RAP) measures have been taken – on land, at sea, and in the air – to reassure Allies in the eastern part of the Alliance.

Moreover, a series of longer-term measures have been launched to adapt NATO’s forces and command structure, so that the Alliance will be better able to react swiftly and decisively to sudden crises. Such adaptation includes enhancing and tripling the size of the NATO Response Force, enhancing Standing Naval Forces, developing a more ambitious exercise programme, accelerating decision-making and improving planning processes. While the RAP has been mostly implemented, it is clear that NATO continues to face a new strategic reality: an arc of uncertainty and instability around its periphery, which requires further adaptation.

Two triggers

The decision to strengthen the Alliance’s deterrence and defence posture was triggered by two developments. The first was Russia’s military doctrine, the scale and pace of its military modernisation, and above all, its aggressive rhetoric, aggressive actions against neighbours, and increased military activity and provocations close to NATO’s borders.

Russia’s seamless employment of all tools and capabilities at its disposal – from hybrid activities, to conventional military threats and nuclear saber-rattling – has been especially disconcerting for Allies, since it appears to lower the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons in Russia’s approach to conflict. The deployment of Anti-Access/Area Denial capabilities that reach into NATO territory and international airspace and waters – from the High North, through the Baltic and Black Seas to the eastern Mediterranean – has added further complication, not least in terms of NATO’s freedom of movement.

At the 2014 NATO Summit in Wales, Allies agreed to step up readiness to ensure that NATO can respond swiftly and firmly to new security challenges. © German Army Press Office

The second development that triggered the strengthening of the Alliance posture has been the rapid degradation of the security situation in the South. Failed states and civil wars, the spread of Daesh and its attacks on the population of Allied cities, and the massive refugee flow towards Europe, taken together, have created a significant strategic challenge to the Alliance.

Deterring and defending against a non-state actor with state-like capabilities and aspirations, such as Daesh, has presented a particularly complex conceptual as well as practical challenge to the way deterrence and defence has been traditionally conceived by Allies.

Importantly, while different in nature, both challenges can significantly affect the security of all Allies, and each requires a 360-degree approach to security. Russia’s propaganda and espionage is targeted against the Alliance as a whole, and Russia pursues military activities and tests of sovereignty in the East, the South, but also in the North Atlantic. Likewise, the massive migration, as well as the propaganda, recruitment and terrorist attacks perpetrated by Daesh affect, directly or indirectly, the security of all Allies.

The three C’s of Alliance credibility

In light of this changed and evolving security environment, Allies agreed at Warsaw to ‘ensure that NATO has the full range of capabilities necessary to deter and defend against potential adversaries and the full spectrum of threats that could confront the Alliance from any direction.’

Russia’s aggressive actions towards its neighbours and the scale and pace of its military modernization – on display, here, during the Victory Day parade on 9 May 2016 – helped trigger the decision to strengthen the Alliance’s deterrence and defence posture. © REUTERS

As a means to prevent conflict and war, credible deterrence and defence is essential. To this end, Allies have developed a broad approach, which draws upon all of the tools at NATO’s disposal: from civil preparedness and national forces as first line of defence, to cyber defence, missile defence, conventional forces, and nuclear deterrence as the fundamental guarantee of Alliance security.

Credibility is essential for successful deterrence. Alliance credibility can be pictured as a three-legged stool, comprising cohesion, capability and communication. Take away one leg, and the stool topples over.

• Cohesion

With the existential threat posed by the Soviet Union gone, the Alliance’s unity and solidarity have not been truly tested over the last two decades. Russia’s resurgence, however, and the pressure of the southern challenges, have brought Allies closer together.

Beyond concern over Russia’s actions, the spread of so-called Islamic State (or Daesh) and its attacks on the population of Allied cities also served to spur efforts to strengthen NATO deterrence and defence.

As a clear signal of solidarity, all Allies have contributed to measures to reassure Allies in the eastern part of the Alliance and have also agreed a set of tailored measures to assure Turkey in the south.

The round table of the North Atlantic Council is a powerful multiplier of solidarity. Although there are perpetual intra-Allied debates and discussions on details and costs, once forged, NATO’s consensus is rock solid. Russia’s persistent effort to undermine this solidarity has actually reinforced it.

• Capability

Robust military capability is another indispensable element of credible deterrence. Despite significant military downsizing and defence spending cuts over many years, NATO remains the most powerful military alliance in the world. No country or group of countries could seriously challenge NATO in a direct major conflict.

However, this does not mean that potential adversaries could not be tempted to exploit an apparent time-space advantage, reinforced by Anti-Access/Area Denial capabilities, on the Alliance’s periphery. After all, at least one potential adversary has been actively exercising such scenarios, and tested them in real-time.

This is why NATO decided to enhance its forward presence in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, and to establish a tailored forward presence for the Black Sea region. The multinational nature of this enhanced forward presence creates a tripwire function necessary to signal to the potential adversary that any aggression against an Ally will be met by NATO military forces from across the Alliance, and from both sides of the Atlantic. This is to avoid any ambiguity or misunderstanding, and to make it clear that a potential aggressor would be engaging in a conflict not with, for example Estonia or Poland, but with NATO as a whole.

Together with the national home defence forces, the forward deployed battlegroups would also form an important element of defence in these countries. They would be quickly reinforced by the Alliance’s NATO Response Force and, if needed, the follow-on reinforcing forces.

At the 2016 NATO Summit in Warsaw, Allies agreed to ‘ensure that NATO has the full range of capabilities necessary to deter and defend against potential adversaries and the full spectrum of threats that could confront the Alliance from any direction.’ © NATO

In the case of a major conflict scenario, reinforcement enabled by high readiness, deployability and sustainability of Allies forces remains the central element of NATO’s defence strategy. From an operational perspective, this is essential to ensure timely availability of Allied forces where and when needed, rather than fixing the Alliance’s forces in one theatre.

The South represents a different kind of challenge and requires a different approach to deliver a comprehensive effect of assurance and protection of Allies, and deterrence of potential adversaries. Here, NATO is adapting through a combination of robust intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance capability for strategic anticipation; an expeditionary capability to respond rapidly to any developing contingency; and enhancing the defence capacity of partners in the region to provide for their own security.

Ultimately, NATO’s entire command structure and force structure – as well as Allies, individually and collectively – need to be prepared and ready to defend each other from any threat from any direction.

• Communication

NATO’s resolve needs to be clearly and unambiguously communicated to avoid misunderstanding and miscalculation by any potential adversary. A good example of such communication is the speech delivered by Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Munich Security Conference in February 2016.

As a clear signal of solidarity, all Allies have contributed to measures to reassure Allies in the eastern part of the Alliance and, at Warsaw, Allied leaders decided to enhance NATO’s forward presence in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, as well as in the Black Sea region. © NATO

He underscored that Russia’s rhetoric, posture and exercises of its nuclear forces, aimed at intimidating neighbours, is undermining trust and stability in Europe. While reminding the audience that NATO’s deterrence ‘also has a nuclear component’, he noted that for NATO, ‘the circumstances in which any use of nuclear weapons might have to be contemplated are extremely remote.’ But he also emphasised that ‘no one should think that nuclear weapons can be used as part of a conventional conflict’, as ‘it would change the nature of any conflict fundamentally’. In other words, Russia would not be allowed to escalate its way out of a failing regional conventional conflict through a limited use of nuclear weapons.

Allies conveyed the same message in the Warsaw Summit Communiqué by stating that “if the fundamental security of any of its members were to be threatened however, NATO has the capabilities and resolve to impose costs on an adversary that would be unacceptable and far outweigh the benefits than an adversary could hope to achieve.”

The Communiqué as a whole should be read as a clear and comprehensive public statement on NATO’s aims and intentions, including with regard to deterrence and defence. It can be safely assumed that it is not only read by Allied audiences, but also by potential adversaries.

The challenges of continuous adaptation

The Warsaw Summit is neither the beginning nor the end of the Alliance’s adaptation. It is, however, an important waypoint towards a strengthened Alliance deterrence and defence posture. As work progresses, it will need to address a number of challenges.

Joint intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance is an essential capability required to improve situational awareness and the ability to respond to challenges emanating from the South. © NATO

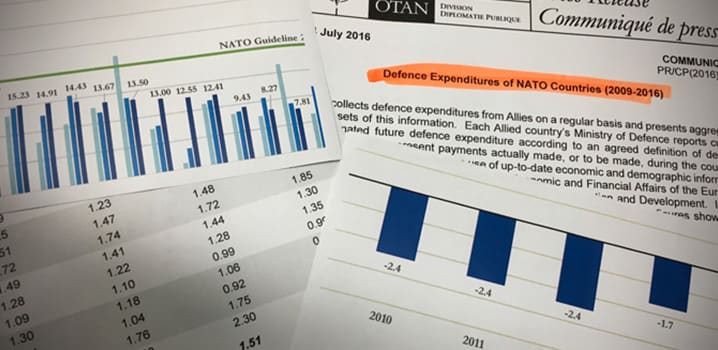

The price tag: Freedom does not come free. Two per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) should not appear an insurmountable target for the richest club of countries in the world. But NATO still has a long way to go: only five Allies currently meet the NATO guideline to spend a minimum of two per cent of their GDP on defence, and only ten Allies meet the NATO guideline to spend more than 20 per cent of their defence budgets on major equipment and research and development.

However, NATO may have turned the corner: collectively, Allies’ defence expenditures have increased in 2016 for the first time since 2009. In two years, a majority of Allies have halted or reversed declines in defence spending in real terms.

Dialogue: Allies made clear in Warsaw that deterrence has to be complemented by meaningful dialogue. NATO remains open to a periodic, focused and meaningful dialogue with a Russia willing to engage on the basis of reciprocity in the NATO-Russia Council. The aim is to avoid misunderstanding, miscalculation, and unintended escalation, and to increase transparency and predictability.

These efforts, however, will not come at the expense of ensuring NATO’s credible deterrence and defence. Although Russia has yet to stop its aggressive rhetoric, hybrid meddling in neighboring countries and provocative military activities around NATO borders, let alone reverse its illegal annexation of Crimea, NATO remains ready for dialogue. The recent meetings of the NATO-Russia Council illustrate the importance of such a dialogue.

While progress has been made over the past couple of years, some member states still have a long way to go to meet NATO guidelines on defence spending.

Non-state actors: Deterrence theory assumes the rationality of actors. Reality curtails that rationality in two major ways: first, any interaction between two rational actors often produces sub-optimal and irrational outcomes. Second, different actors adhere to different notions of rationality. A modern, democratic state actor will not be able to judge what a terrorist group, such as Daesh, deems ‘cost’, ‘benefit’ or ‘unacceptable damage’.

Deterrence, defence against and, ultimately, defeat of such actors, requires a broader approach and a concerted effort by the international community. To address the root causes of instability in the Middle East and North Africa, which has spawned groups like Daesh and its affiliates, NATO is enhancing its contribution to the broader efforts of the international community to project stability through crisis management, partnerships and capacity building programmes for the partners in the region. A series of measures have also been agreed to respond to the threat posed by Daesh and similar groups, including ensuring that this threat is appropriately monitored and assessed and that relevant plans are kept up to date.

Overall coherence: Finally, in the longer run, NATO will need to consider the overall coherence of its evolving deterrence and defence posture. This includes capabilities, exercises, and plans, across all domains – air, maritime, land and cyber, missile defence and nuclear. NATO leaders took important decisions in this regard at the summits in Wales as well as Warsaw. Implementation is now underway.

However, while NATO continues to adapt to new threats and challenges, one thing remains constant: the greatest responsibility of the Alliance is to protect and defend its territory and populations against attack, as set out in Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. A strengthened deterrence and defence posture will ensure that it can continue to fulfil that responsibility and no one should doubt NATO's resolve if the security of any of its members were to be threatened.