NATO enlargement and Russia: myths and realities

In his address to the Russian Parliament on 18 April 2014, in which President Putin justified the annexation of the Crimea, he stressed the humiliation Russia had suffered due to many broken promises by the West, including the alleged promise not to enlarge NATO beyond the borders of a reunited Germany. Putin touched a responsive chord among his audience. For more than 20 years the narrative of the alleged “broken promise” of not enlarging NATO eastward is part and parcel of Russia’s post-Soviet identity. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that this narrative has resurfaced in the context of the Ukraine crisis. Dwelling on the past remains the most convenient tool to distract from the present.

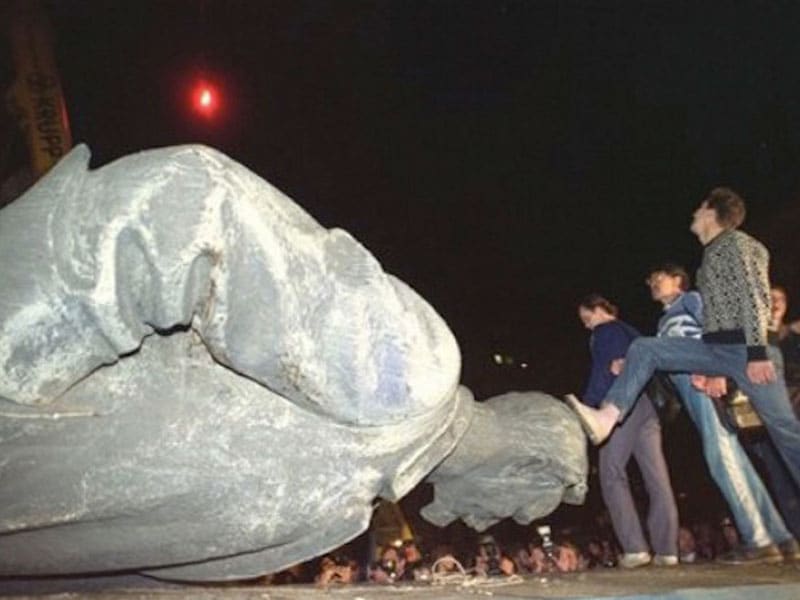

But is there any truth to these claims? Over recent years countless records and other archival material has become available, allowing historians to go beyond the interviews or autobiographies of those political leaders who were in power during the crucial developments between the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the Soviet acceptance of a reunified Germany in NATO in July 1990. Yet even these additional sources do not change the fundamental conclusion: there have never been political or legally binding commitments of the West not to extend NATO beyond the borders of a reunified Germany. That such a myth could nevertheless emerge should not come as a surprise, however. The rapid pace of political change at the Cold War’s end produced its fair share of confusion. It was a time where legends could easily emerge.

The origins of the myth of the “broken promise” lie in the unique political situation in which the key political actors found themselves in 1990, and which shaped their ideas about the future European order. Former USSR leader, Mikhail Gorbachev’s reform policies had long spun out of control, the Baltic countries were demanding independence, and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe were showing signs of upheaval. The Berlin Wall had fallen; Germany was on the road to reunification. However, the Soviet Union still existed, as did the Warsaw Pact, who’s Central and Eastern European member countries did not talk about joining NATO, but rather about the “dissolution of the two blocks”.

Thus, the debate about the enlargement of NATO evolved solely in the context of German reunification. In these negotiations Bonn and Washington managed to allay Soviet reservations about a reunited Germany remaining in NATO. This was achieved by generous financial aid, and by the “2+4 Treaty” ruling out the stationing of foreign NATO forces on the territory of the former East Germany. However, it was also achieved through countless personal conversations in which Gorbachev and other Soviet leaders were assured that the West would not take advantage of the Soviet Union’s weakness and willingness to withdraw militarily from Central and Eastern Europe.

It is these conversations that may have left some Soviet politicians with the impression that NATO enlargement, which started with the admission of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland in 1999, had been a breach of these Western commitments. Some statements of Western politicians – particularly German Foreign Minister Hans Dietrich Genscher and his American counterpart James A. Baker – can indeed be interpreted as a general rejection of any NATO enlargement beyond East Germany. However, these statements were made in the context of the negotiations on German reunification, and the Soviet interlocutors never specified their concerns. In the crucial “2+4” negotiations, which finally led Gorbachev to accept a unified Germany in NATO in July 1990, the issue was never raised. As former Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze later put it, the idea of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact dissolving and NATO taking in former Warsaw Pact members was beyond the imagination of the protagonists at the time.

Yet even if one were to assume that Genscher and others had indeed sought to forestall NATO’s future enlargement with a view to respecting Soviet security interests, they could never have done so. The dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 later created a completely new situation, as the countries of Central and Eastern Europe were finally able to assert their sovereignty and define their own foreign and security policy goals. As these goals centered on integration with the West, any categorical refusal of NATO to respond would have meant the de facto continuation of Europe’s division along former Cold War lines. The right to choose one’s alliance, enshrined in the 1975 Helsinki Charter, would have been denied – an approach that the West could never have sustained, neither politically nor morally.

The NATO enlargement conundrum

Does the absence of a promise not to enlarge NATO mean that the West never had any obligations vis-à-vis Russia? Did the enlargement policy of Western institutions therefore proceed without taking Russian interests into account? Again, the facts tell a different story. However, they also demonstrate that the twin goals of admitting Central and Eastern European countries into NATO while at the same time developing a “strategic partnership” with Russia were far less compatible in practice than in theory.

When the NATO enlargement debate started in earnest around 1993, due to mounting pressure from countries in Central and Eastern Europe, it did so with considerable controversy. Some academic observers in particular opposed admitting new members into NATO, as this would inevitably antagonise Russia and risk undermining the positive achievements since the end of the Cold War. Indeed, ever since the beginning of NATO’s post-Cold War enlargement process, the prime concern of the West was how to reconcile this process with Russian interests. Hence, NATO sought early on to create a cooperative environment that was conducive for enlargement while at the same time building special relations with Russia. In 1994 the “Partnership for Peace” programme established military cooperation with virtually all countries in the Euro-Atlantic area. In 1997 the NATO-Russia Founding Act established the Permanent Joint Council as a dedicated framework for consultation and cooperation. In 2002, as Allies were preparing the next major round of NATO enlargement, the NATO-Russia Council was established, giving the relationship more focus and structure. These steps were in line with other attempts by the international community to grant Russia its rightful place: Russia was admitted to the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the G7 and the World Trade Organisation.

The need to avoid antagonising Russia was also evident in the way NATO enlargement took place in the military realm. As early as 1996, Allies declared that in the current circumstances they had “no intention, no plan, and no reason to deploy nuclear weapons on the territory of new members”. These statements were incorporated into the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, together with similar references regarding substantial combat forces and infrastructure. This “soft” military approach to the enlargement process was supposed to signal to Russia that the goal of NATO enlargement was not Russia’s military “encirclement”, but the integration of Central and Eastern Europe into an Atlantic security space. In other words, the method was the message.

Russia never interpreted these developments as benignly as NATO hoped. For Russian Foreign Minister Primakov, the signing of the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997 was merely “damage limitation”: As Russia had no means to stop NATO enlargement, it might as well take whatever the Allies were willing to offer, even at the risk of appearing to acquiesce in the enlargement process. The fundamental contradiction of all NATO-Russia bodies ‒ that Russia was at the table and could co-decide, but could not veto, on key issues ‒ could not be overcome.

However, these institutional weaknesses paled against the background of real political conflicts. NATO's military intervention in the Kosovo crisis was interpreted in Moscow as a geopolitical coup by a West that was bent on marginalising Russia's status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council. NATO's missile defence approach, though directed at third countries, was interpreted by Moscow as an attempt to undermine Russia's nuclear second strike capability. Worse, the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine and the “Rose Revolution” in Georgia brought to power elites who envisioned the future of their respective countries in the EU and NATO.

Against this background, Western arguments about the benevolence of NATO enlargement never had – and probably never will have – much traction. Appealing to Russia to acknowledge the benign nature of NATO's enlargement misses a most essential point: NATO enlargement ‒ as well as the enlargement of the European Union ‒ is designed as a continental unification project. It therefore does not have an “end point” that could be convincingly defined either intellectually or morally. In other words, precisely because the two organisations’ respective enlargement processes are not intended as anti-Russian projects, they are open-ended and – paradoxically – are bound to be perceived by Russia as a permanent assault on its status and influence. As long as Russia shirks an honest debate about why so many of its neighbors seek to orient themselves towards the West, this will not change – and the NATO-Russia relationship will remain haunted by myths of the past instead of looking to the future.