What you see depends on where you are standing…and the view of energy security from here on the banks of the Potomac River, is surely quite different from that on the banks of the Seine, the Thames, the Vistula, or of Faxafloi Bay.

In 1973, the United States were so traumatized by an oil embargo by members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) that we still use a proper noun to describe the “1973 Oil Crisis”. Though we soon stopped burning oil to generate electricity and made gradual progress improving the fuel efficiency of our vehicle fleet—such that our nation’s oil demand peaked in 2005—the near-monopoly oil still has in fueling our transport sector is our acute energy security vulnerability. Given that monopoly, and transport’s literal circulatory role in all commerce, oil remains the lifeblood of our economy.

The United States has a relatively secure supply of oil. With rising domestic oil production, we are once again importing less than half of our oil demand and we have a diverse, reliable set of foreign oil suppliers—Canada supplies the most with 24% of our imports. Yet “energy security” implies not only secure access to supplies, but also at affordable prices. Irrespective of the provenance of the oil we combust, we are not insulated from the economically disruptive oil price spikes that can be the consequence of a supply disruption anywhere in the world.

The 1973 Oil Crisis inspired the creation of the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 1974, precisely to organize collective action by large oil importers to cope with oil supply disruptions and price manipulations by OPEC. The IEA has largely done the job it was created to do within the limited range of action its members have to address global supply disruptions. It was only a year ago that IEA members executed a coordinated release from their strategic oil reserves in order to try to mitigate the spike in global oil prices caused, in part, by the disruption to Libya’s oil exports to Europe during its civil war and NATO’s campaign.

The 2011 Libya experience came just one year after the adoption of NATO’s new Strategic Concept at the Lisbon Summit, which speaks directly to a new NATO role in addressing energy security. The Strategic Concept demands that NATO “develop the capacity to contribute to energy security, including protection of critical energy infrastructure and transit areas and lines, cooperation with partners, and consultations among Allies on the basis of strategic assessments and contingency planning…”. The violence in Libya directly threatened the energy security of NATO members by disrupting the flow of its light, sweet crude to European oil refineries and the flow of natural gas through pipelines to Italy. NATO took pains not to destroy Libya’s oil infrastructure during the course of the campaign, but this hardly constitutes a demonstration of a new capacity.

This recent experience begs the question: What else, if anything, should NATO have done to address the energy security threat posed to the NATO members by the conflict in Libya?

From here in Washington, the answer seems to be: nothing. IEA’s role to address the energy security threat the Libyan conflict posed to its members was relatively straightforward. Though the membership of the IEA and NATO are not identical, the overlap is considerable, with 19 of 28 Alliance members in the IEA, leaving out only small oil consumers.

If one agrees that NATO should not attempt to adopt a competing and redundant role for addressing oil supply disruptions—still the top energy security challenge here in the United States—what useful role should it play?

It bears reminding that the Alliance’s recent attention to energy security was, to a large extent, focused by the natural gas supply disruptions many of its European members experienced as Russia became perceived as an unreliable supplier when Gazprom turned off the flow of gas in the winters of 2006 and 2009 in the course of contract disputes with Ukraine, a key transit state. With soft echoes of Cold War rhetoric about the malevolent and capricious Russian bear, much ink and breath has since been used to expound upon the necessity for and mechanisms by which those countries most dependent on Russian gas could and should diversify their suppliers and supply routes.

Without rehashing those arguments and ideas, let us ponder: what role, if any, would NATO play in what many have this asserted is the chief energy security vulnerability on the East side of the Atlantic. Would NATO finance the construction of gas interconnectors, LNG receiving terminals, pipelines to Caspian-region suppliers, or other critical infrastructure? No. Would NATO enforce the unbundling terms of the European Union’s Third Energy Package that Gazprom so despises? No. Would NATO require its members to meet certain energy efficiency targets in its gas-heated buildings and key industries? No.

These are all activities best left to European national governments and the EU itself. And though the EU membership and NATO membership are not identical, akin to IEA membership, the membership overlap between NATO and the EU is considerable, with 21 of 25 European members of NATO also members of the EU, with only Albania, Croatia, Iceland and Norway outside of the EU fold. In the event of an Article 5 attack on a member, NATO would strive to protect endangered critical energy infrastructure, but this has always been the case.

It would seem that NATO faces a conundrum of sorts: Its new Strategic Concept puts energy security squarely in its mission, but the two energy security matters its members are most fixated upon—the reliability of oil and natural gas supplies and stable energy markets—are being addressed by other institutions that are better suited to deal with these issues. However, just because NATO has no primary role to play in the foremost energy security challenges of its members does not mean that it has no role to play at all.

NATO is first and foremost a military alliance. NATO plays a critical energy security role by protecting critical energy infrastructure and transit—a role explicitly embraced in the new NATO Strategic Concept. Presently, for example, it is playing this role by protecting the ships and sea lanes into and out of the Persian Gulf from a potential Iranian threat.

NATO can develop “the capacity to contribute to energy security” in valuable novel ways as well. At the 2012 NATO Summit, held in Chicago this past May, our leaders officially endorsed the creation of a new NATO Energy Security Center of Excellence. There are three emerging energy security challenges to which the new NATO Energy Security Center of Excellence should endeavor to bring attention across the Alliance to these challenges and their potential solutions:

1) Operational energy

It is plainly obvious that the national militaries that make up the Alliance have a strategic weakness in their energy supply chains and energy usage. It is a tragedy that NATO convoys regularly come under lethal attack in Afghanistan while delivering fuel to operate inefficient vehicles and inefficient diesel generators used to power inefficient devices. The fully-burdened cost of fuel—not the price paid to the wholesaler, but the true price of getting that fuel to the frontlines of the battlefield—is an excess that no military expecting combat can easily afford as national budgets across the Alliance tighten. NATO should catalyze cooperation throughout the Alliance to identify and implement the means by which our militaries can be made stronger by becoming more energy efficient and less reliant on lengthy fuel supply chains.

2) Cyber-security of the energy sector

One of the most serious energy security threats NATO Allies face today was not a threat at all until fairly recently: the threat of cyber attacks disabling the energy sector critical infrastructure from afar. Kinetic attacks on critical energy infrastructure—such as a power plant or electrical grid—is less likely to occur within the Alliance than a successful cyber attack. Our systems are vulnerable and the cascading effects of a sustained failure in the power sector could be terrible, affecting essential basic services such as water purification.

NATO should be applauded for having the foresight to include both energy security and cyber security in the domain of its relatively new Emerging Security Challenges Division. Similarly NATO’s newly established Energy Security Center of Excellence and the new NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence should work very closely together on the area of cyber attacks on the energy sector and disseminate the expertise and best practices from Alliance members.

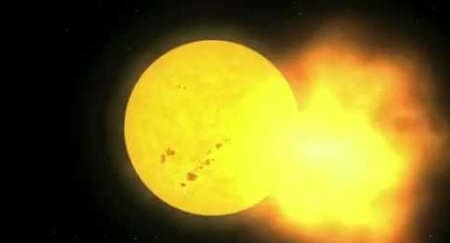

3) Extreme space weather

NATO has a long and proud history defending against and doing contingency planning for low probability, catastrophic events. Severe space weather—and its impact on energy infrastructure in particular—is one of those types of events against which NATO Allies should collectively work to defend themselves. Though space weather would at first seem to be an esoteric subject of discussion between nations’ space agencies, extreme space weather events observed in the not-too-distant past would have dire consequences if repeated in today’s electronics-dependent world. According to NASA, a repeat of the 1859 super solar flare (known as the “Carrington event”) could produce year-long blackouts over enormous territories. In 1989, a less severe geomagnetic storm disrupted power transmission in Canada knocking out power in Quebec for 6 million people and melting power transformers.

Clearly the expertise on solar weather resides with our space agencies and astronomers, but our militaries must consider the potential security consequences and take preventive measures and do contingency planning for low frequency, high impact extreme space weather events.

IN SUMMARY, the greatest energy security challenges confronting NATO members are the same potentially disruptive critical energy supply interruptions that have threatened our economies for years: namely, oil and gas imports from non-NATO members. In the United States, the threat of oil supply disruptions and oil market instability is still our paramount energy security threat. That said, the IEA was created in the wake of the 1973 Oil Crisis precisely to address this concern and there does not appear to be a useful new role for NATO in this space. From this side of the Atlantic, we recognize that new European anxieties over the reliability of some Alliance members’ natural gas imports from Russia provided the motivation for including energy security so prominently in the NATO Strategic Concept that was adopted in 2010. However, there is little NATO can do to address those anxieties, as NATO is incapable of making the necessary infrastructure investments and market reforms necessary to mitigate those continental vulnerabilities.

However, NATO already plays a critical energy security role by protecting critical energy infrastructure and transit and can play a valuable role in spreading expertise throughout the Alliance about emerging and overlooked energy security challenges. Specifically, NATO’s new Energy Security Center for Excellence should pay close attention to the issues of: operational energy, cyber-security for the energy sector, and extreme space weather. This is not to say that there are no other emerging or overlooked energy security threats that NATO ought to pay attention, but it would constitute a very fine start to the Alliance’s newly assumed responsibilities.