September 11th, 2001 has often been called the day that changed everything. This might not be true for our day to day life, but in security, it really marked a new era. Together with the Twin Towers, our traditional perceptions of threats collapsed. The Cold War scenario that had dominated for over 50 years was radically and irrevocably altered.

The threat didn’t have a clear (national) sender's address anymore. Territorial boundaries became meaningless, as did the military rules of space and time. Using civil airplanes as tools for a terrorist attack showed that almost everything could be turned into a weapon, anytime. Suddenly nothing seemed to be impossible or unthinkable anymore.

This is also almost the same description of cyber threats.

Over the past 20 years, information technology has developed greatly. From an administrative tool for helping optimise office processes, it is now a strategic instrument of industry, administration, and the military. Before 9/11, cyberspace risks and security challenges were only discussed within small groups of technical experts. But, from that day it became evident that the cyber world entails serious vulnerabilities for increasingly interdependent societies.

Evolution of the Cyber Threat

The world-wide-web, invented just a couple of decades before, has evolved. But so have its threats. Worms and viruses have transformed from mere nuisances to serious security challenges and perfect instruments of cyber espionage.

Distributed Denial of Service (DDOS) attacks, so far basically seen as nothing more than the online form of “sit-in blockages”, have become a tool in information warfare.

And finally, in June 2010 the malware “Stuxnet” became public, something like a “digital bunker buster” attacking the Iranian nuclear programme. With this the early warnings of experts since 2001 have become reality, suggesting that the cyber dimension might sooner or later be used for serious attacks with deadly consequences in the physical world.

A three week wave of massive cyber-attacks showed that NATO member’s societies, highly dependent on electronic communication, were also extremely vulnerable on the cyber-front.

During the Kosovo-Crisis, NATO faced its first serious incidents of cyber-attacks. This led, among other things, to the Alliance’s e-mail account being blocked for several days for external visitors, and repeated disruption of NATO's website.

Typical for that time, however, the cyber dimension of the conflict was merely seen as hampering NATO’s information campaign. Cyber-attacks were seen as a risk, but a limited one in scope and damage potential, calling only for limited technical responses accompanied by low scale public information efforts.

It took the events of 9/11 to change that perception. And it still needed the incidents in Estonia in summer 2007 to finally draw full political attention to this growing source of threats to public safety and state stability. A three-week wave of massive cyber-attacks showed that NATO member’s societies were also exceedingly vulnerable on the cyber-front.

The growing awareness of the seriousness of the cyber-threat was further enhanced by incidents in the following years.

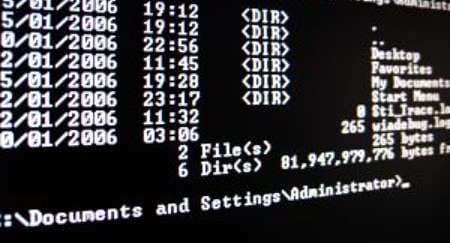

In 2008, one of the most serious attacks to date was launched against American military computer systems. Via a simple USB-stick connected to a military-owned laptop computer at a military base in the Middle East, spy software spread undetected on both classified and unclassified systems. This established what amounted to a digital beachhead, from which thousands of data files had been transferred to servers under foreign control.

Since then, cyber-espionage has become an almost constant threat. Similar incidents occurred in almost all NATO nations and – most prominent – recently again in the United States. This time more than 72 companies including 22 government offices and 13 defence contractors were affected.

These numerous incidents over the past five to six years amount to a historically unprecedented transfer of wealth and closely guarded national secrets into basically anonymous and most likely malicious hands.

Stuxnet showed the potential risk of malware affecting critical computer systems managing energy supplies

Massive attacks on government websites and servers in Georgia took place during the Georgia-Russia conflict, giving the term of cyber-war a more concrete form. These actions did no actual physical damage. They did, however, weaken the Georgian government during a critical phase of the conflict. They also impacted on its ability to communicate with a very shocked national and global public.

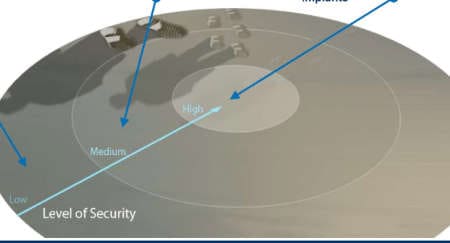

As if such reports were not threatening enough, the Stuxnet worm that appeared in 2010 pointed to a further qualitative quantum leap in destructive cyber war capabilities. In the summer of 2010, news spread that approximately 45,000 industrial Siemens control systems worldwide had been infected by a tailored trojan virus that could manipulate technical processes critical to nuclear power plants in Iran. Although the damage assessment still remains unclear, this showed the potential risk of malware affecting critical computer systems managing energy supplies or traffic networks. For the first time, here was proof of cyber attacks potentially causing real physical damage and risking human lives.

A balanced threat-assessment

These incidents make two things clear:

- So far, the most dangerous actors in the cyber-domain are still nation-states. Despite a growing availability of offensive capabilities in criminal networks that might in future be used also by non-state actors like terrorists, highly sophisticated espionage and sabotage in the cyber-domain still needs the capabilities, determination and cost-benefit-rationale of a nation state.

- Physical damage and real kinetic cyber-terrorism has not taken place yet. But the technology of cyber-attacks is clearly evolving from a mere nuisance to a serious threat against information security and even critical national infrastructure.

There can be no doubt that some nations are already investing massively in cyber capabilities that can be used for military purposes. At first glance, the digital arms race is based on clear and inescapable logic, since the cyber warfare domain offers numerous advantages: It is asymmetrical, enticingly inexpensive, and all the advantages are initially on the attacker’s side.

Furthermore, there is virtually no effective deterrence in cyber warfare since even identifying the attacker is extremely difficult and, adhering to international law, probably nearly impossible. Under these circumstances, any form of military retaliation would be highly problematic, in both legal and political terms.

The cyber-defence capabilities are equally evolving and most Western nations have considerably stepped up their defences in recent years

On the other hand, however, the cyber-defence capabilities are equally evolving and most Western nations have considerably stepped up their defences in recent years. Good cyber defence does make these threats manageable, to the extent that residual risks seem largely acceptable, similar to classic threats.

But instead of speaking of cyber war as a war in itself – portraying digital first strikes as a “Digital Pearl Harbour” or the “9/11 of the cyber world” – it would be far more appropriate to describe cyber-attacks as one of many means of warfare. The risks of cyber-attacks are very real and growing bigger. At the same time, there is no reason to panic, since for the foreseeable future these threats will neither be apocalyptic nor completely unmanageable.

Facing the Challenge

NATO is adapting to this new kind of security challenge.

Already one year after 9/11, NATO issued an important call to improve its “capabilities to defend against cyber attacks” as part of the Prague capabilities commitment agreed in November 2002. In the years following 2002 however, the Alliance concentrated primarily on implementing the passive protection measures that had been called for by the military side.

Only the events in Estonia in the spring of 2007 prompted the Alliance to radically rethink its need for a cyber defence policy and to push its counter-measures to a new level. The Alliance therefore drew up for the first time ever a formal “NATO Policy on Cyber Defence”, adopted in January 2008, that established three core pillars of Alliance cyberspace policy.

- Subsidiarity, i.e. assistance is provided only upon request; otherwise, the principle of sovereign states’ own responsibility applies;

- Non-duplication, i.e. avoiding unnecessary duplication of structures or capabilities – at international, regional, and national levels; and

- Security, i.e. cooperation based on trust, taking into account the sensitivity of the system-related information that must be made accessible, and possible vulnerabilities.

This constituted a qualitative step forward. It also paved the way for the basic decision taken in Lisbon to continuously pursue cyber defence as an independent item on NATO’s agenda.

Initiated by events like Kosovo in 1999 and Estonia in 2007 and profoundly influenced by the dramatic changes in international threat perception since September 2001, NATO had laid out the foundations for building a “Cyber Defence 1.0”. It had developed its first cyber defence mechanisms and capabilities, an drawn up an initial Cyber Defence Policy.

With the Lisbon decisions in November 2010, the Alliance then successfully laid the foundations for a self-directed, factual examination of the issue. In doing so, NATO is not only giving existing structures like the NATO Computer Incident Response Capability a much-needed update, but also beginning to jointly, as an alliance, face up to very real and growing cyber defence challenges.

In line with NATO's new Strategic Concept the revised NATO Policy on Cyber Defence defines cyber threats as a potential source for collective defence in accordance with NATO's Article 5. Furthermore, the new policy - and the Action Plan for its implementation - provides NATO nations with clear guidelines and an agreed list of priorities on how to bring the Alliance's cyber defence forward, including enhanced coordination within NATO as well as with its partners.

Once the Lisbon decisions have been fully implemented, the Alliance will have built up an upgraded “Cyber Defence 2.0”. By doing so, the Alliance is proving again that it is up to the task.