At the end of November, the United Nations’ World Health Organization assessed the risk of a pandemic to be level three out of six. This indicates that a new flu strain has appeared in humans, but not yet started spreading between people. Elin Gursky and John Sandrock look at the possible consequences of a flu pandemic and ask how prepared NATO and Alliance countries are.

A fowl holocaust? More than 150 million birds have died or been slaughtered due to bird flu (© Reporters )

In 2004, the Atlantic Council of the United States hosted a two-day “Topics in Terrorism” conference that considered future threats and targets. The topics covered the spectrum of biological, nuclear and explosive threats, radiological dispersal devices, attacks on food and water systems, and assaults using industrial-grade chemicals and toxins, such as chlorine and cyanide.

During the same period of the meeting, 23 people in four countries died following infections involving a virus which had not been featured in the conference – H5N1 (or ‘bird flu’).

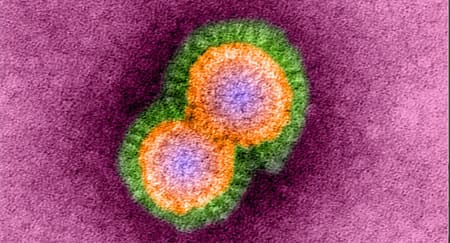

First isolated in 1996 in China’s Guangdong Province, the H5N1 virus has spread to over 50 countries on three continents since 2003. The virus has killed tens of millions of birds in over 50 countries. It has stricken more than 330 humans in 12 countries, with just over 200 dead. The virus’s rapid spread and high pathogenicity have contributed to a mortality rate averaging 61 per cent.

Some countries have been particularly hard hit. Indonesia has had 112 people infected since June 2005, with a fatality rate approximating 80 per cent. The virus’s ability to jump from one species to another has been seen in an increasing number of non-domestic bird species and some mammalian species including pigs and cats.

So far, the H5N1 virus does not have the ability to pass from person to person. It is possible, however, that the virus could evolve into a contagious form through association with human flu viruses. It could even gain this ability on its own through mutation.

Fifteen of 26 NATO countries experienced non-human outbreaks between 2005 and 2007. Were the virus to develop into an influenza pandemic contagious between humans, the consequences for the transatlantic community could be disastrous. Is the Alliance prepared?

Lessons from the past

The death rate associated with the H5N1 virus has provoked global concern reminiscent of the Great Influenza of 1918. That was a pandemic blamed for killing “more people than any other outbreak of disease in human history”, with an estimated death toll of between 21 million and 100 million people in two years.

The 1918 influenza pandemic spread across the United States (US) from its suspected Kansas origin – and then worldwide. Soldiers, often incubating the disease without showing its symptoms, huddled in training camps and deployed on troopships en route to Europe.

First isolated in 1996 in China’s Guangdong Province, the H5N1 virus has a mortality rate averaging 61 per cent

In the collision of the Great Influenza with the Great War, about 57,000 American troops died from influenza while the United States was at war, spreading disease to military and civilian populations through disembarkation points in France.

The disease moved to Spain, then Portugal and Greece. A transport brought cases to Bombay in late May, and the virus spread by railroad lines to Calcutta, Madras, and Rangoon. In the Indian Army, nearly a quarter of the troops who caught the disease died. In June and July, surges in death rates were seen across Great Britain. July 1918 saw cases in Denmark and Norway, and August in Holland and Sweden.

The influenza also reached Shanghai at the end of May, spreading like a tidal wave across the whole country. Everyday life came to a total standstill.

It was as true then as in ancient times: more soldiers die from disease than from conflict-associated wounds.

Given the potential lethality of H5N1, it is difficult to overestimate the devastating impact of a major and sudden outbreak. What would have happened had the 1,200 NATO staff deployed to Pakistan in 2005 come into contact with a mutant, virulent strain of H5N1?

After all, NATO medical personnel treated more than 3,000 Pakistani medical cases. Could they have returned to their homes in Europe? Would they have brought the infection with them? Would they have had to survive in place?

What’s at stake?

This scenario presents two issues of grave concern. The first is the expanded role of NATO forces in the event of a pandemic. The second is the need to ensure that they are protected from illness should such deployments become necessary.

During the Cold War, NATO troops were trained and equipped to operate and fight in a lethal chemical environment. Are they now trained, equipped, and able to operate in a hostile viral environment?

Various NATO documents, such as NATO Military Policy on Civil-Military Co-operation, address various aspects of NATO medical planning and preparedness – with the very notable exception of specifics on how NATO would react to a pandemic emergency.

The 2007 NATO Logistics Handbook points out in its section headed ‘Responsibility for the Health of NATO Forces’ that:

‘Nations retain the ultimate responsibility for the provision of medical support to their forces allocated to NATO. However, upon Transfer of Authority, the NATO commander shares the responsibility for the health and medical support of assigned forces.’

Under the heading of ‘Force Health Protection’, the handbook goes on to note that:

‘Disease and Non-Battle Injury (DNBI) is an ever-present health risk to personnel. The primary responsibility of medical support is the maintenance of health through the prevention of disease and injury…. Whenever there is a suspected or confirmed outbreak of a contagious disease, the commander must be given medical advice on Restriction of Movement.’

And under ‘Planning’ it says:

‘Medical support concepts, plans, structures, and operating procedures must be understood and agreed by all involved. The medical support should ensure a surge capability to deal with peak casualty rates in excess of expected daily rates.’

This last sentence is symptomatic of a general approach. Even a surge above ‘expected daily rates’ cannot begin to reflect the potential of a pandemic.

Filling the gaps

Some planning has taken place on national levels. For example, in the US, an H5N1 vaccine manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur was approved in April 2007 by the US Food and Drug Administration. It has purchased and stockpiled the vaccine for distribution by public health officials, if needed.

Funding in the United States has been set aside to allow the Department of Health and Human Services to continue to develop a vaccine for the US population within six months of the first sign of a pandemic. The goal is to give antiviral coverage to at least 25 per cent of Americans. Currently, there are sufficient antiviral medications (such as Tamiflu) to treat 40 million Americans. Some $81 million is also to be spent on an H5N1 vaccine and an antiviral drug supply specifically for the military, consistent with the US Pandemic Flu Plan.

In addition, the United Kingdom has developed a strategic plan to coordinate the efforts of public and private organizations in the event of a full-blown pandemic.

Have national authorities or operational commanders fully considered the potential severity of a sudden outbreak among deployed troops?

Despite this progress, the following awkward questions still need answers.

Have national authorities or operational commanders fully considered the potential severity of a sudden outbreak among deployed troops?

Has NATO considered how the Alliance would react to a breakdown of civil authority in the wake of a pandemic? Could deployed forces be immunized quickly enough?

In the face of a pandemic, would national authorities “chop” their soldiers for deployment, even if the North Atlantic Council agreed that a deployment is essential to restoring order?

The traditional attitude that medical concerns are a national responsibility may have restricted optimum consideration of the potential consequences for NATO.

Unfortunately, given the far more immediate urgency of Allied operations in Afghanistan, NATO leaders may have put the pandemic infection problem into the “too difficult at the moment” basket.

If true, this is unwise. The potential impact is simply too significant, and the long term consequences may be too severe.