The World Bank defines post conflict reconstruction (PCR) as 'supporting the transition from conflict to peace through rebuilding a country's socioeconomic framework'. How far can NATO go in this PCR role? Here, Manjana Milkoreit gives her personal view that NATO could be the best equipped organization for PCR.

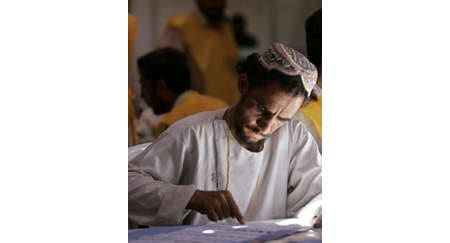

Pointing to the future: Afghanis have been able to vote following NATO's intervention in the country - a prime example of reconstruction efforts helping people to help themselves (© AP / Reporters)

It's always interesting to look at international security issues and ask 'what if?' What if the United States had a chance to restart its invasion in Iraq? What if NATO could redesign its Afghanistan mission from the beginning? What if Europe got another shot at stabilising the Balkans? What would they do differently? It's fair to assume all of them would look longer and harder at post conflict reconstruction (PCR).

Prior to the 1990s, few anticipated that PCR would become one of the most serious, lasting challenges of post-Cold War military engagements. There was little planning, training or even knowledge of who specialized in it. This lack of preparation has led to the failure of nation-building attempts by both state and international organizations - and in some cases, their efforts have even worsened the crises.

There are many questions about new post-conflict environments, such as who should be financially, legally and morally responsible. But few question one issue: the world ought to be better prepared to engage in PCR.

International conflicts since the early 1990s have shown that military operations are just one aspect of stabilization and post-conflict reconstruction. PCR incorporates military and civilian tasks across five distinct areas:

- providing security (including military and policing functions);

- delivering essential services (i.e.water, electricity, health services);

- creating political structures (i.e. writing a constitution, electoral system);

- creating an economic infrastructure;

- and facilitating reconciliation between the formerly fighting groups

The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have not only highlighted the need for a comprehensive civil-military approach to PCR: they have also drawn unprecedented political attention to the issue. This opens a window of opportunity for a major institutional change.

Step forward NATO

NATO could be the key to solving this seemingly intractable challenge.

Why? Because it already has unique expertise in military stabilization. And it is reaching into the civil-political sphere, where it is treading carefully on unfamiliar ground. NATO should become an expert in civil reconstruction as much as it already is in military stabilization.

Despite NATO's position, an international effort to create stronger PCR capabilities should focus on turning NATO into the international reconstruction organization: by making it the central actor in a PCR network of global partnerships with non-member states, regional and international organizations. This institutional change would provide a clear focal point for PCR issues - and streamline the currently scattered resources.

Why NATO?

PCR requires a combination of military and civilian expertise. No single organization has both of these capacities combined under one roof. Creating an effective cooperation interface between military and civilian personnel poses significant cultural and coordination challenges. NATO is the organization best suited to accomplish this task for four reasons:

First, NATO has mastered the military component of PCR: providing security and stability in crisis regions after violent conflict.

Second, NATO is already testing a combined military-civilian approach with Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) in Afghanistan. PRTs and a military-civilian NATO have essentially the same task: a comprehensive approach to reconstruction, drawing on both military and civilian expertise and capabilities. Developing NATO as the world's primary reconstruction organization builds on and expands this civil-military cooperation.

So far, the international community has failed to adequately apply the post-conflict reconstruction lessons from the 1990s to the first conflicts of the 21st century

Third, NATO's role as a regional defence alliance depends on permanent cooperation, communication, and joint planning between numerous military entities. This expertise would be vital in coordinating and managing diverse PCR networks. And NATO's recent focus on building partnerships with states and organizations bodies well for the creation of PCR networks not just on the military, but also civil-PCR side.

Fourth, NATO is redefining its purpose and mission. NATO needs to demonstrate its ability to adapt continuously to new challenges in 21st century military engagements. Reshaping its mission, ambitions, and geographic reach by serving on a global rather than regional basis would build on NATO's strengths. NATO is uniquely poised to add a tremendous amount of value relative to other national, regional or international organizations.

From idea to reality - what would this mean for NATO?

First, it would imply a changed mission. NATO is already a major actor in PCR, but making PCR a priority alongside issues such as security, deterrence and defence and partnerships would require a change of organizational character and a major expansion of NATO's mission.

NATO's transition from a geographic to a functional Alliance gives it a global role, emphasizing the importance of its global partnerships. The language of the North Atlantic Treaty is also flexible enough to allow for further changes without the political difficulty of adjusting the Treaty text.

Second, introducing reconstruction capacities into NATO's structure poses organizational and cultural challenges. Moving from a mainly military identity to a combined civilian-military one means creating the largest integrated civil-military interface in the world.

While NATO's existing military structure would remain in place, its civilian structure would be extended to include a reconstruction branch comprising all non-military PCR activities. The integration of these two branches would require close coordination, smooth communication, skilled leadership and careful management.

Civil and military, old and new: reconstruction efforts have to bridge many divides, especially that of conflict and peacetime (© NATO)

Effective civil-military integration will allow joint training and operational familiarity of the civil and military capacities ahead of operations in a crisis. This will facilitate better PCR planning at the outset of crises along with improved implementation.

The following departments could be established within the organization's civilian structure.

A civilian police force: Considering the integration of the existing European Gendarmerie Force (EGF), NATO should develop quickly deployable policing units, trained and coordinated in joint training centres like the EGF headquarters in Vicenza, Italy.

A legal-political department will have numerous essential tasks relating to reconstruction: With the expertise and capacity to design country-specific constitutions, electoral systems, judicial and administrative structures, it will support post-conflict state structures in their formation. Its tasks could include civil society capacity-building.

The engineering and infrastructure department is a prime example of the potential for civil-military interfacing within NATO. Providing basic services (electricity, water, etc) in the aftermath of conflict is essential to limit humanitarian crises-and military engineering corps have repeatedly demonstrated these capabilities. But PCR also requires capacity for long-term urban and rural civil infrastructure plans, requiring civilian skills. The interface between military expertise and civil field-engineering before field deployments enables reconstruction of lasting civil infrastructure immediately after the violence ends.

An economic development department will work in close cooperation with the engineering department and institutions like the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme, Non-governmental organizations and other country experts.

A department specializing in reconciliation issues will have the difficult task of creating unity between the people of a conflict-torn country. Reconciliation specialists, negotiators and psychologists will collaborate with local experts.

PCR requires a combination of military and civilian expertise. No single organization has both of these capacities combined under one roof

A "Crisis Watch" department, which monitors ongoing conflicts, will maintain a minimum level of alertness and preparation, and gather data on countries where NATO deployment might become necessary.

A "Lessons Learned" unit will gather, aggregate, and analyse information on NATO's reconstruction experiences to feed back into the organization to improve its effectiveness.

Third, NATO needs to be at the heart of an effort to build civil-military global reconstruction partnerships.

NATO's reconstruction branch has to build its own basic expertise and understanding of reconstruction. Rather than duplicating existing approaches, NATO should leverage these resources, turning itself into a coordinator and manager of outside expertise through global partnerships.

The first steps on the path to change

So far, the international community has failed to adequately apply the post-conflict reconstruction lessons from the 1990s to the first conflicts of the 21st century.

The need and opportunity for change is now. The first visible attempts to build PCR capacities should be consolidated, expanded and coordinated under a single, capable organization: NATO.

Inevitably, the proposed reform would increase NATO's funding needs. However, short-term set up costs have to be weighed against huge potential savings, particularly in quality of life and economic terms. These benefits will become clear if adequate reconstruction capacity is in place when the next conflict region calls for help from the international community.

The Alliance should initiate international research to investigate NATO's possible reform into an international reconstruction organization. Dedicated conferences and commissioned studies, integrating civil and military experts on PCR, organizational design for civil-military interfacing and programme evaluation, could lead to recommendations on how to structure and fund this reform.

Whether or not NATO adopts this new mission, it is important that individual NATO members assess the scale of the post-conflict reconstruction challenge and the current (lack of) capacity. They should develop a coherent strategy to fill the holes in the current system - at both national and international levels.