Lawrence S. Kaplan explores the document's origins, impact and long-term significance.

In the almost sixty-year history of NATO, there have been few milestones that portended major changes in the direction of the Alliance. The two most visible have been the Korean War with its impact on the structure of the organisation between 1950 and 1952 and the implosion of the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1991 that began with the tearing down of the Berlin Wall. A third major change had as much impact on intra-Alliance relations as it had on the Cold War: the Harmel Report of 1967. Now forty years old, the Harmel initiative reflected the influence of the smaller members of the Alliance upon the larger powers, particularly upon the superpower, the United States. NATO's acceptance of the message in that report blunted centrifugal pressures that might have led to the Alliance's dissolution. It also set NATO on a course that ultimately led to the end of the Cold War.

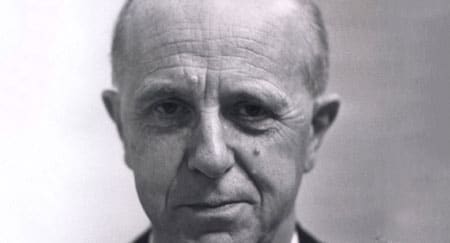

Pierre Harmel, Belgium's foreign minister, initiated the "Harmel exercise" in 1966 "to study the future tasks which face the Alliance, and its procedures for fulfilling them in order to strengthen the Alliance as a factor for a durable peace." The resulting report to the Brussels meeting of the North Atlantic Council in December 1967 has rightly gone down in NATO history as the voice of smaller nations urging that détente as well as defence be equally the Alliance's major functions in the immediate future. Recognising the continuing potential for crises, particularly over the German question, the report did not overlook the importance of "adequate military strength and political solidarity to deter aggression." But its main thrust was to recognise that the Allies must work toward a more stable relationship in which political issues, especially the status of the Germanies, could be resolved. The assumption in this report was that there were signs that Soviet and East European policymakers saw advantages in working toward a stable settlement in Europe. Détente was a means to this end.

The spade work for the report was not confined to members of the smaller powers. Among the rapporteurs of the four sub-groups of a special group that the North Atlantic Council established under then-Secretary General Manlio Brosio were Karl Schutz, J.H.A. Watson, and Foy Kohler from the respective foreign offices of the Federal Republic of Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. Watson and Schutz led the sub-group 1 on East-West relations, while Kohler was rapporteur for sub-group 2 on general defence. Belgium's Paul-Henri Spaak chaired sub-group 3 on inter-Allied relations, and Dutch Professor C.L. Patijn of the University of Utrecht served in sub-group 4 on developments outside the NATO area. The presence of American, British, and German diplomats in the framing of the Harmel report was all-important to converting Harmel's initial interest in a strictly European caucus into a broader program embracing the entire Alliance; emphasising European solidarity against US pressure was too narrow a focus.

The written reports of the sub-groups, begun in April 1967 and completed by September, were the substance of the International Staff Secretariat's summary document presented to the foreign ministers in December. Rather than entitling the report "The Future of the Alliance", they called it "Future Tasks of the Alliance" to remind the Allies that the Alliance's mission would continue beyond its twentieth birthday in 1969.

This collaboration among large and small powers in the working group reflected a major shift from the atmosphere that had produced the Report of the Committee of Three on Non-Military Collaboration in NATO in 1956. The "Wise Men's" report was essentially a cri de coeur of smaller nations that had felt excluded from the decision-making process. They were asking for genuine collaboration in NATO councils. That report was overshadowed by the Suez crisis which in itself was an illustration of the marginalisation of the smaller NATO Allies. While the Council endorsed the report in May 1957, its specific recommendation of "expanded cooperation and consultation in early stages of policy formation" was largely ignored over the following decade.

Why détente was to occupy such an important place in NATO's history and why the smaller nations' voices came to be heard more clearly by the mid-1960s were both consequences of the changing geopolitical scene. Just as the Anglo-French Suez debacle deflected attention from the advice of the Three Wise Men, so a host of events within the Alliance and between the two blocs served to promote the goals of the Harmel Report. A primary agent was the sense that the Cold War had entered a new stage with the ending of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 and the Berlin crisis in 1964. In both these circumstances the Soviet Union withdrew from the brink of war-in Cuba by withdrawing its missiles from the island and in Berlin by signing a treaty with the German Democratic Republic that omitted mention of the status of West Berlin. The result was an assumption, particularly among the European Allies, that the Soviet Union and the Warsaw bloc were increasingly moving toward normal, if often adversarial, relations with NATO. The language of the Harmel report suggests that the subsequent relaxation of tensions would not be "the final goal but is part of a long-term process to promote better relations and to foster a European settlement."

The Harmel Report has rightly gone down in NATO history as the voice of smaller nations urging that détente as well as defence be equally the Alliance's major functions

Charles de Gaulle's France provided a second though unwitting element in the background of the Harmel Report. By withdrawing from the military structure of the Alliance, President de Gaulle signalled his belief that military confrontation with the Soviet bloc was a thing of the past, and that the Soviet Union could be treated not as an abnormal entity seeking the destruction of the West but as a potential partner in a new European order. Continuing defence measures would be irrelevant in this scenario for the future of Europe.

The Harmel report in this context represented NATO's response to the Gaullist challenge. The report made clear that the success of the military pillar made détente possible. Building on this foundation, NATO could develop credible means of expanding political and economic contacts with the Warsaw bloc. While de Gaulle agreed with détente as the means of achieving a new relationship with the Soviet adversary, he was dissatisfied with the role the North Atlantic Council would have in coordinating national policies to achieve this objective. The problem was resolved when France agreed to the general concept of political consultation without having to accept the prospect of an integrated political structure. Rather than risk further isolation within the Alliance, France reluctantly agreed to a downsized version of the working groups' specific recommendations. The result was a document that consisted of only 17 paragraphs.

France's withdrawal from SHAPE also opened opportunities for the smaller nations to raise their voices in the Defence Planning Committee and the Nuclear Planning Group without the threat of France's opposition. The United States cultivated the Nuclear Planning Group in particular as a substitute for the failed Multilateral Force. While nuclear weapons would not be owned by Europeans, there would be European participation, even if limited, in nuclear planning. All the Allies with the exception of France would acquire information about nuclear matters that had been denied prior to 1966. The collegiality requested in the Three Wise Men's report gave the smaller nations a stake in the future of NATO that they had previously lacked. Harmel's name on the report was a symbol of genuine change.

There was a third transformation in the international scene that played a part in the completion of the Harmel exercise: namely, the Vietnam War's impact on the US role in NATO. This war in Southeast Asia initially had won support of NATO Allies on the grounds that the United States served a common cause in resisting Communist expansion by its aid to South Vietnam. This judgment may have been valid in the early 1960s, but it had lost credibility with Europeans after the rapid influx of American troops in 1965 had converted the Vietnam conflict into an American war. By 1967 most of the Allies had become strong opponents of the war, partly because of the damage it inflicted on civilians, but largely because they sensed that the war was diverting American resources and troops from US obligations to Europe.

For its part, the United States recognised that the Vietnam War was weakening the nation's role in NATO as well as creating internal tensions within the nation itself. Détente looked to be an opportunity for the United States to extract itself from the Vietnam morass. America's reasons for promoting détente were not identical with Europe's. Nor was there full consensus over its meaning. American policymakers did not share the conviction that the Cold War had evolved to the extent that détente could achieve equal status with defence in NATO's relations with the Soviet bloc. But strained domestic circumstances along with hopes of European and Soviet help in resolving the Vietnam conflict at the time of the Harmel report made it imperative that the United States accept its parameters. The transatlantic superpower had lost some of its authority by the end of the decade but its participation in NATO remained vital to the success of détente as well as to the continuing defence of the Alliance.

The Harmel Report's pressure for détente discomfited the United States even as it was compelled to recognise its necessity. Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, General Lyman L. Lemnitzer was concerned that the Allies had accepted the Warsaw Pact's invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 with excessive equanimity, and had qualms about the Ostpolitik of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt. Ostpolitik was a by-product of the German decision in the Harmel negotiations to play down the issue of reunification in favour of improving relations with East Germany and the Soviet Union.

Under other conditions the United States might have opposed the Federal Republic's approach to East Germany. But in the shadow of the Vietnam War, the spirit of détente was seen as a means of solidifying American links to its Allies as well as easing the way out of Vietnam. Moreover, the Nixon administration embraced its own version of détente as National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger sought to tie the Soviet Union into a balance-of power system rather than banish it beyond the diplomatic pale.

The Soviet bloc's violent overthrow of the Dubcek government in Prague in August 1968 reminded NATO of the continuing need for defence preparations. It did not, however, divert the Allies from following the recommendations of the Reykjavik declaration at the North Atlantic Council meeting in June 1968 by signalling an interest in pursuing mutual and balanced force reductions. Brandt's initiative seemed to open the way for negotiations for mutual and balanced troop reductions in Vienna in 1973. In the same year the Harmel Report inspired the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe that produced the Helsinki Final agreement of 1975. Unlike their behaviour at the Vienna talks, the Soviets were anxious to conclude an agreement to legitimise their post-war boundaries. But the Helsinki arrangements also provided an agreement to uphold human rights and extend freedom of information in all signatory countries.

The ripple effects of the Harmel Report spread through the 1970s and into the 1980s as arms control was an ongoing subject of negotiations between East and West. The initial wave of optimism over détente ended by the mid-1970s when the Soviets and NATO engaged in a new arms build-up, but the seeds sown by the Harmel report remained fertile. Concern about détente may be found in the dual track initiative of 1979 when NATO linked the deployment of intermediate range nuclear missiles in Europe to renewed efforts in arms control. The American guarantee to Europe's defence was balanced by its commitment to work toward an arms control agreement with the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union joined the United States a decade later to terminate the Cold War, they were, in effect, responding to the Harmel Report's message.