Pierre Lellouche offers his thoughts ahead of the Riga Summit.

During my tenure as President of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly - a body independent from the Alliance itself as legislative and executive bodies should be - I have worked hard in improving the Assembly's work and in developing its reach so as to gradually transform an originally limited role as a consultative forum for national parliamentarians into a tool for "democratic control" within NATO. I believe the parliamentarians in the Assembly have a crucial role to play, as they do in the Council of Europe or the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Not only are parliamentarians responsible for voting defence budgets in their national Parliaments, they also support both the enlargement process through ratification of the accession protocols to the Washington Treaty and national troops deployment in peace-making or peace-building operations under the UN or NATO flag.

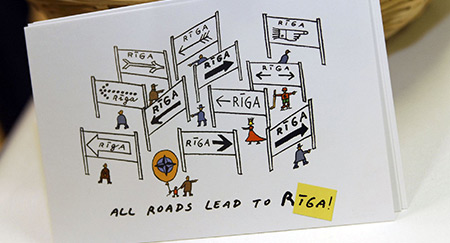

In addition, NATO parliamentarians discuss questions in a climate of friendship and fair debate that is often more free and open than at NATO itself. The Assembly can also place new issues on the agenda of our Committee meetings or Plenary sessions, often well before they are discussed by the North Atlantic Council. For example, there has been a lot of talk in recent years over how the Alliance should best keep its relevance. I have no doubt that NATO parliamentarians can and will make valuable contributions to this debate. The Riga Summit in November will constitute a unique opportunity to continue this dialogue with NATO Heads of State and Government.

The state of the Alliance

NATO's position today is a paradox. On the one hand, the Alliance has survived the geopolitical revolution caused by the end of the Soviet threat. Our Alliance has played a fundamental role in consolidating peace, for example on the European continent by a decisive contribution to settling conflicts in the Balkans and by its highly effective commitment to combating terrorism, particularly in Afghanistan.

At the same time, the Alliance has provided itself with new capabilities such as the NATO Response Force. The Alliance has also successfully developed partnerships with the European Union in its security and defence dimension, as we see in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and on another level with Russia, Ukraine and other members of the Partnership for Peace. The Alliance remains extremely attractive to many: waves of enlargement in 1999 and 2004 helped to eliminate divisions in Europe by bringing in former adversaries from the Warsaw Pact and nations freed from Soviet domination.

Still other candidate countries have clearly shown their willingness to join the Euro-Atlantic community of values and have embarked upon the necessary reforms with determination. I am convinced that we must give these countries more assistance, encouragement and support because their accession will help to reinforce the stability of the European continent. At our May 2006 session in Paris, our Assembly reaffirmed that the door of the Alliance remains open to those democracies able and willing to accept the obligations of membership, in particular with regard to the aspirations previously expressed by Ukraine and, more recently, by Georgia.

On the other hand, the future of the Alliance seems in many ways unclear. Fifteen years after the end of the Cold War, the raison d'être of our organisation is an open question. Is NATO still, as Chancellor Angela Merkel said in February 2006 in Munich, "the primary venue" for discussing Allied security issues? Should it become a "NATO with global partners", as NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer said at the most recent Munich Conference on Security Policy? Should it "go global" to the extent that it would welcome countries such as Japan, Australia or Israel as full members, as recently suggested by the former Spanish President, José Maria Aznar? Or should the Alliance be made secondary to ad hoc coalitions of the willing, to which Donald Rumsfeld, the American Defense Secretary, referred to in his famous formula "the mission determines the coalition"? In the immediate aftermath of September 11, the Alliance was used neither in Afghanistan nor in Iraq. Some commentators wonder about the solidity of the Alliance and its capacity for joint action in the event of a new major international crisis in, for example, Iran.

In addition, there are weaknesses and pending issues on the European side, increased by the negative result of the constitutional referendum in France and the Netherlands last year, which abruptly stopped the political integration process within the European Union. To date, one can hardly see any European military power emerging, given that together the 25 EU member countries spend 40 per cent of what America spends on defence and are capable of lining up 10 per cent of the projection capabilities of American forces. More than ever, Europe is torn between three groups of countries: neutrals who stick to their neutrality status even after the end of the Cold War; "euro-atlanticists" who favour the pillar approach within NATO; and "euro-gaullists" who aim to build up Europe as a counterweight to US power and global dominance.

Furthermore, a measure of "enlargement fatigue" that is now obvious in the European Union (i.e. Turkey and Ukraine) and within NATO, with, for example, the coolness shown by some European governments towards Georgia's candidature. More than ever, NATO is in clear need of a fundamental reassessment of its raison d'être, its long-term goals and the balance between its American and European poles. Such a reassessment should be a primary focus of the discussions in Riga, where, in my view, heads of state and government should agree to launch a "wise men's group report" on this question and others of central importance to the Alliance.

The challenges ahead

The first challenge is clear and simple: in order for our values to prevail, democracies have to stay united in this dangerous world. The distressing experiences in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Afghanistan and especially Iraq have given us a wealth of lessons to contemplate on both sides of the Atlantic. America alone cannot do everything, and neither can the Europeans. My deeply-held conviction is that a strong transatlantic link remains both in Europe's and America's best interests. However, in order to ensure the continuation of a robust and meaningful alliance, two conditions must be met: on the American side, there must be a clear commitment to accept not just consultations, but joint decision-making in central strategic questions. This means encouraging rather than opposing European defence integration. The second condition is that European defence integration should not be conceived in opposition to the US but as a contribution to Euro-Atlantic security. This calls for a truly ambitious partnership that requires Europeans to make sustained defence efforts more along the lines of those made by the United Kingdom or France, by far the leading European Allies in terms of current defence spending.

We have the obligation to support the values of the Alliance, particularly in nations that have chosen to embark on the democratic path

The second challenge concerns terrorism and proliferation. From New York to Washington, from Madrid to London, and from Amman to Sharm el Sheikh, terrorism has continued unabated in recent years, and the latest declarations by al-Qaida leaders prove that we should expect nothing and negotiate nothing with those who show contempt for human life. The most dreadful danger lies ahead where terrorism and proliferation meet - what my friend André Glucksmann calls the "collision between Auschwitz and Hiroshima". During what I would call the first nuclear age - the era of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) - protecting populations was believed to be destabilising insofar as it weakened deterrence. In today's world, it is impossible to expect that nuclear deterrence will deter terrorists, and it is equally unreasonable not to take all necessary steps to protect our populations.

NATO countries need, therefore, to significantly enhance their response capabilities in terms of civil emergency planning and coordination. At the same time, NATO countries should accelerate international cooperation in order to prevent trafficking in fissile materials and to dismantle terrorist networks. They should also come forward with new initiatives aimed at preventing proliferation, like the one outlined on 19 September in Vienna by former US Senator Sam Nunn that would create an international nuclear fuel bank under the auspices of IAEA, thus depriving potential proliferators of a convenient pretext to start enrichment activities. Only by taking these challenges seriously will we be able to reduce significantly the potentially lethal threat they pose to western civilisation and to our very existence.

Our third challenge is to set right our relations with the Muslim world, the next-door neighbour of the Atlantic Alliance. One of NATO's oldest Allies, Turkey, has a Muslim majority, and Turkey's role for strengthening the Alliance's southern flank can hardly be overestimated. The Alliance is also present in theatres of operations such as Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan whose populations are partly or majority Muslim. Rather than an alleged clash of civilisations between East and West, I believe we are witnessing a fight within the Muslim world itself between those radicals who are trying to misuse an anti-western interpretation of the Islamic religion in order to advance their own political agendas (what I have called "green fascism") and those moderate or secular Muslims who are trying to reconcile the Islamic world with modernity. NATO nations cannot remain indifferent to the outcome of this fight.

Afghanistan today is a test case for the Alliance that incorporates, to varying degrees, all three challenges outlined above. A failure of the NATO operation there would not only mean a dramatic setback for democracy and secularism in the Muslim world, but would also encourage fanatics and Jihadist movements worldwide. All our efforts should therefore be mobilised to defeat the Taliban and stabilise the country. Let us be clear: much more needs to be done in terms of force generation and "boots on the ground" to guarantee success.

Another challenge is to resolve the "frozen" conflicts of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh or Transdnestria. The President of Georgia, Mikhail Saakashvili, and his counterpart from Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, both addressed our Spring Session in Paris. We also had a useful exchange of views with our Russian colleagues from the Duma in a joint seminar held in Sochi last June. NATO should encourage all parties involved to intensify their efforts, in good faith, to bring about peaceful settlements to these disputes in accordance with international law and recognised OSCE principles. At the same time, any attempts to make use of these conflicts in order to bring South Caucasus nations back into rival "areas of influence" are doomed to fail. On the contrary, a clear prospect for NATO membership would in turn help solve these conflicts by reinforcing democracy, economic growth, and the rule of law. Our governments should stand ready to contribute on the ground, in close cooperation with other institutions such as the EU, the UN or the OSCE, to any peace-support operation that might be launched.

Last, but not least, the Alliance needs to invest in consolidating democracy. This is the case today with Georgia, a country that clearly deserves our support. Our Assembly passed a resolution during the Spring Session calling for the Alliance to start an "Intensified Dialogue" with Georgia on membership issues "as soon as possible", and we were heartened when our governments formally initiated this dialogue last September. I would agree that an intensified dialogue towards NATO membership is "a path, not a given", but we shall not spare our efforts to ensure that, on that path, Georgia can count on the determined support of our democracies.

In Ukraine, NATO parliamentarians who monitored the recent Ukrainian legislative elections in March 2006 were impressed by the political maturity shown by the Ukrainian people. NATO should support efforts to ensure that the democratic achievements of the "Orange Revolution" are not wasted as a result of political in-fighting and corruption scandals. Another question will be whether the Ukrainian people will be in a position to choose freely their own security arrangements - as they are entitled to do under OSCE agreements.

This leads me to my biggest cause of concern in this part of the world. If the progress of democracy can be contagious, then reaction can be too. For many years, the NPA has tried to establish normal relations with Russian counterparts by debating with our Russian colleagues from the Duma in the NATO-Russia Commission, the Parliamentary equivalent of the NATO-Russia Council. We cannot fail to notice the increasingly anti-democratic and anti-western tone of statements made by our Russian colleagues, something that mirrors what has been described as a growing "values gap". And while the rhetoric is deteriorating, there has also been a worrying divergence of interests on a wide range of issues affecting Russia's domestic and foreign policy, including the lack of an independent judiciary, attacks on freedom of the press, growing concerns over energy security, the Iranian nuclear issue and Moscow's attempts to re-establish its influence - often in a very brutal manner - over its former empire.

It is time for us to wake up and face the facts, however unpleasant they may be. We must now develop a common strategy as to how we can best promote and support democracy, in and around Russia, in order to reduce these tensions. We shall not forget that NATO was founded in 1949 as an Alliance based on democratic values, and we have the moral obligation to support those values, particularly in those nations that have chosen to embark on the democratic path. As in the past, we will have to face new challenges, fight battles, and win.