Gerald Knaus and Marcus Cox examine Bosnia’s peace five years after the guns fell silent and assess prospects for a self-sustaining process. Gerald Knaus is director of the European Stability Initiative (ESI), a Berlin-based think tank and advocacy group working to help restore stability to southeastern Europe. Marcus Cox is ESIs senior Bosnia analyst.

Signing ceremony: Presidents Slobodan Milosevic (left), Franjo Tudjman (centre) and Alija Izetbegovic (right) have all left office since signing the Dayton Agreement on 14 December 1995. (Reuters photo - 222Kb)

The fifth anniversary of the Dayton Agreement comes at a time of celebration in the Balkan region. The regimes of Slobodan Milosevic and Franjo Tudjman, the nationalist leaders who fought to carve a Greater Serbia and Croatia from the ruins of the former Yugoslavia, have been decisively rejected by their own people, replaced with governments hoping to lead the two states back into the European fold. No longer trapped between predatory neighbours intent on stirring up trouble, the prospects of long-term peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia) have never looked better.

Yet within Bosnia, the mood is pessimistic. A recent opinion poll suggested that 70 per cent of young people would leave the country, if given the chance. Although Bosnians are increasingly more concerned with jobs than ethnic grievances, the main political parties continue to neglect their many pressing needs in favour of narrow and often chauvinistic political agendas. The November 2000 elections, which some in the international community had hoped would turn into a contest between reform-oriented moderates and backward-looking nationalists, became instead a vote against incumbents, whatever their political views. The moderate Social-Democratic Party (SDP) replaced the long-time governing Party of Democratic Action as the leading political force in areas of the country dominated by Bosnian Muslims (Bosniacs). In the Serb-dominated parts of the country, however, where a Western-supported government under Prime Minister Milorad Dodik had been in power since 1998, the party founded by indicted war criminal Radovan Karadzic, the Serb nationalist Serb Democratic Party, managed to bounce back and win the elections.

The international peace mission is now facing a number of extremely serious choices. How can it adapt its policies to an environment in which leading political parties continue to question the basic legitimacy of the institutions for which elections are held? What can be learned from the repeated failure to try to bolster individual favourites? And how can the necessary long-term, incremental constitutional and administrative reforms to stabilise the political system continue, when a collapse of public revenues is looming and the international communitys willingness to focus on Bosnia is decreasing? Can Bosnias fractious political forces be welded into a tolerably effective state, in time to stave off a deepening economic crisis and challenges to the very notion of the Bosnian state?

The twin challenges of recovering from a devastating war and converting a communist system into a free market have so far proved beyond the capacity of the states fragile institutions. Despite more than $5 billion of international reconstruction aid, Bosnias GDP is still less than half its pre-war size. Unemployment remains high and, with average wages well below the subsistence needs of a family, more than 60 per cent of the population lives in poverty. Foreign investors have stayed away, put off by the slow progress of privatisation, the weak legal system, and a myriad of unhelpful regulations. Some governments, including that of Republika Srpska, are barely able to service their foreign debt from month to month.

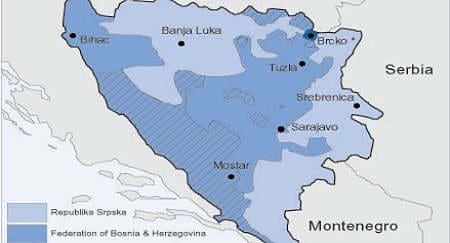

Attempts to stop the economic slide have been frustrated by the weakness of public institutions across Bosnias many tiers of government. From the outset, the Dayton Agreement was recognised as a difficult compromise, creating a state with barely enough central functions to be worthy of the title, while guaranteeing the autonomy of the three communities through a complex system of ethnic power-sharing. State functions are dispersed across two entities, ten federal cantons, 149 municipalities and the internationally administered district of Brcko. Most of these tiers of government are novel creations, and suffer an acute lack of public servants and competent executive organs. The entire structure is so complex and inefficient that, all too often, nobody takes responsibility for addressing pressing social and economic problems.

Because the constitutional organs are weak, real power is exercised behind closed doors, far from public scrutiny or democratic process. The most blatant example of parallel power is the Bosnian Croat parastate of Herzeg-Bosna, which, though formally disbanded in 1994, continues to exercise de facto control over Croat institutions and public finances. In November 2000, the Croat Peoples Assembly, a body with no constitutional status, called a referendum on the status of the Croat people, threatening to constitute itself as a parallel government if its demands were rejected by the international community. In the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, nominally multi-ethnic institutions are in fact split into separate Bosniac and Croat components, with little communication between them. At the state level, the elected representatives often work simply to keep the state from becoming an effective political actor.

So long as the basic administrative structures are weak, elections can do little to foster responsible government. The international community has organised six rounds of voting over the past five years, as though constantly rolling the dice in the hope of producing a better outcome. Its search for so-called moderates has been a frustrating one, and internationally favoured candidates such as Republika Srpskas Prime Minister Milorad Dodik have proved disappointing once in power. Among Bosniacs, the multi-ethnic SDP of Zlatko Lagumdzija is becoming increasingly popular. However, with its electoral base mainly at municipal and cantonal level and dependent on an extremely weak and fractured administrative apparatus, the SDP is in a weak position to effect substantial reforms in a short period of time. In Serb and Croat-dominated areas, despite widespread disillusionment with the political process, the electorate continues to return the wartime nationalist parties to power.

As international attention in southeastern Europe turns towards the multi-layered problems of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the international mission in Bosnia is seen by some as it was seen in 1996, as a race against time. Bosnia is not yet a self-sustaining structure, and the consequences of a premature withdrawal could be catastrophic, not just for Bosnia but across the region. However, it is also clear that international aid cannot continue to cover for the weakness of the Bosnian state with-out a clearer perspective on how this state and its institutions could become viable.

In frustration at the weak performance of national institutions, the international mission has become more assertive, to the point where the Office of the High Representative (OHR) and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) have become central pillars of the constitutional order. Unable to extricate itself without risking the collapse of the state, and yet unable to hand over responsibility to national authorities, the international mission now finds itself in a role it never wanted to play.

In the first phase of the peace process, the tasks of the international mission were set according to traditional ideas of UN peacekeeping, backed with an unusually strong military force. The Dayton Agreement contained an elaborate calendar of military obligations, and with 60,000 troops at its disposal, the NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR) ensured that they were followed to the letter. The international forces deployed rapidly along the cease-fire lines, physically separating the armies, placing weaponry into cantonment sites, and demobilising the forces to peace-time levels. Detailed balance of force agreements and close IFOR supervision of military movements reduced the security dilemmas between the parties. The Train and Equip programme, carried out by US contractors outside NATO authority, built up the Federation militaries to create a balance of power between the former warring parties. The International Police Task Force accomplished a similar downsizing and balancing of the police forces.

The international community threw itself into the reconstruction of the war-ravaged country with impressive energy. By the end of the Bosnian War, more than 2,000 kilometres of roads, 70 bridges, half the electricity network and more than a third of the housing had been destroyed. In the face of enormous logistical difficulties, the World Bank and the European Commission coordinated a $5.1 billion reconstruction programme. By 1999, over a third of the housing had been repaired and most urban infrastructure had been restored to pre-war levels, from telephone lines, electric power generation and water services to the number of primary schools per pupil.

It was in these practical tasks that the international mission enjoyed its greatest success. Its political agenda was more modest, limited to organising elections in the shortest possible time-frame. Elections were thought to be the key to removing extremists from the political landscape and ushering in a new era of liberal democracy. They were also a necessary first step in convening the new state institutions. As it transpired, wartime nationalist leaders were returned to power in successive rounds of elections, strengthened and legitimated with their new constitutional mandates, leaving the international community with no alternative but to carry out its mission in partnership with the same individuals who had prosecuted the war.

So long as the international community was spending its money liberally on reconstructing the country, the peace mission met with little resistance. However, once the immediate military and humanitarian imperatives were met and attention turned to the creation of a viable state, the international community came face to face with intense political resistance.

Post-war Bosnia was effectively divided into three territorial zones, bordered by the cease-fire lines. Each enjoyed functional independence in political and economic terms, and was ruled by a separate administration under the control of one of the three armies. As in any protracted conflict, these quasi-states developed power structures with vested interests in the abnormalities of the wartime environment, which became strongly resistant to change. Elements in these regimes had close links with smuggling and organised crime, bringing wealth and power to individual political leaders. The combination of the threat of violence and the promise of rewards typically the redistribution of the spoils of war and the allocation of public sector employment allowed them to monopolise political power within their own ethnic group. In the tradition of the old Yugoslav Communist Party, the nationalist parties used patronage networks to keep public institutions subordinate to their will.

These wartime power structures dominated political life in post-war Bosnia. What seemed to outsiders to be intractable ethnic hatred often turned out to be crude, self-interested political manipulation. The political elite used nationalist rhetoric as a tool to control their own population, playing on collective fears in order to harden the boundaries between ethnic groups. Almost any international objective that went beyond the distribution of aid, such as promoting refugee returns or the creation of a common economic space, posed a threat to the nationalist power structures and met with staunch opposition. Deadlocked on most fronts, the international mission simply forged on with what could be achieved in such an environment, namely physical reconstruction. Inevitably, the disbursement of vast sums of reconstruction aid with a minimum of political or institutional reforms simply helped strengthen the nationalist power structures even further.

It was the continued existence of these parallel systems that frustrated the establishment of the Bosnian state. Real power was exercised behind closed doors. The nationalist parties had no incentive to allow control over their affairs to shift to new institutions, which they could not be sure of controlling. By the simple tactic of refusing to participate, they ensured that the state institutions remained little more than theatres of nationalist politics.

Five years on, the nationalist power structures are fragmenting, undermined by the war-weariness of the population, and the inexorable return of normality to the region. In Republika Srpska, the Karadzic regime began to crumble from the time of the Dayton Agreement, following the split between Pale and Belgrade. The private security forces on which Karadzics highly predatory regime depended were extremely expensive to maintain. A few well-targeted international operations to disrupt his smuggling networks, together with a concerted political campaign to force him out of public office, broke his hold on power.

The Croat para-state of Herzeg-Bosna lasted longer, but is now suffering heavily from the loss of revenues from Croatia following the defeat of the late President Tudjmans Croatian Democratic Union (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica or HDZ) in elections in early 2000. With external subsidies drying up, the parallel structures are increasingly unable to deliver basic public services, let alone the bribes on which their power depends. Divisions in the political machinery are appearing as a result.A handful of senior figures in the Bosnian HDZ are now realigning themselves towards the state and the international community, in search of a more reliable source of revenues. On the other hand, the party leadership under Ante Jelavic has chosen the path of total confrontation with the international community and threatens to withdraw from all institutions.

While this process of decay creates real opportunities for progress, it is also a risky time for the peace process. The nationalist parties remain strong enough to ensure that there is a continuing crisis of governance at all levels of the Bosnian state. As the old systems collapse, the legitimate constitutional structures are simply not ready to take over. The two entities both have chaotic public finances, bankrupt pension funds, bloated and inefficient public sectors, rampant public corruption and neither the skills nor, it seems, the political will to undertake the economic reforms that the country so badly needs.

As a result, while the days of the monolithic nationalist parties may be numbered, they are being replaced not by liberal democracy, but by growing factionalism and institutional decay. A new government, however sincere its reform intentions, will face an uphill battle against this background of weak institutions, diminishing resources and opposition from many quarters. Just when changes in Croatia and Serbia make the dangers of renewed warfare seem remote, the risk for Bosnia is that the chronically weak state will collapse under the weight of a growing economic and political crisis.

In frustration at the constant dissembling of Bosnian politicians, the international community has arrogated a series of bold new powers to itself. From the weak coordinating role envisaged in the Dayton Agreement, the High Representative has been elevated to the central legislative power. In December 1997, the Peace Implementation Council, the intergovernmental authority that oversees the mission, authorised the High Representative to impose laws and to dismiss public officials who obstruct the peace process.

The High Representatives powers have proved extremely useful for bypassing deadlocked state institutions. It was only with these powers that progress has been possible in areas such as wresting control of public broadcasting from the nationalist parties, introducing a common currency, or returning housing and property rights to people ethnically cleansed during the war. Initially controversial, the imposition of laws by the High Representative has now become routine, attracting little response from the Bosnian public or political elites. It does, however, raise a series of questions related to both the implementation of specific laws and the evolution of the constitutional system.

Administrative and resource constraints are as much of a problem for laws imposed as they are for laws regularly adopted. It is, for example, impossible to decree a functioning Bosnian customs service or judiciary into being, and international programmes in these areas have pointed to the need for intensive post-imposition implementation strategies. The successes in the field of the OHR-imposed property legislation are the result of a major managerial effort to ensure that municipal housing offices are actually putting the new laws into effect. In the internationally administered district of Brcko, the major constraint on a large international mission is no longer nationalist opposition but a dangerous shortfall of resources to keep a complex institutional structure alive.

Overall, imposition opens up an ever wider implementation gap, which in the medium term undermines rather than strengthens confidence in the legal system. There is also a constant temptation for outsiders as much as for Bosnian political forces to lobby the High Representative to impose a law to resolve a specific short-term problem or to help a given political favourite. This, however, instead of strengthening trust in young institutions, risks undermining them completely, replacing the arbitrariness of previous regimes with that of the international community.

Trusteeship is a new weapon in the armoury of international interventions, and Bosnia is its first arena. At the end of the day, it can be considered legitimate only if it results in the creation of an effective state, rendering the trusteeship itself redundant. The task of the international mission is now architectural, creating structures that will continue to stand after the external supports are withdrawn.

But there is no magic to the High Representatives powers. He cannot simply decree an effective state into existence. Few of the international agencies in Bosnia have any great experience in the nuts and bolts of institution-building, which requires detailed sectoral expertise. Individual agencies have a tendency simply to plough on with the peacekeeping tasks they are familiar with: reconstruction, monitoring, and still more elections. The question is whether the international mission can successfully change tack at this stage.

A number of institution-building initiatives have had impressive results. A Central Bank has been created under an international governor, which successfully introduced a new currency in 1998. An intensive and long-running programme by the European Unions Customs and Fiscal Assistance Office to reform customs administration has given impressive results. The Independent Media Commission, a new licensing authority for broadcast media, has helped to promote the independence of the media. At the municipal level, efforts to create local administrative structures capable of enforcing property laws are gradually achieving results. Each of these has required a clear strategic vision as to how to bring different forms of international leverage to bear on a complex problem.

The international community now needs to think through the structures required to complete the state-building project. In May 2000, the Peace Implementation Council set out a list of core institutions whose creation should be treated as a priority. These include central regulators in network industries such as telecommunications, energy and transport, an independent and professional civil service, and guaranteed revenue sources for the state. To rise to this challenge, the international mission will need to move beyond battling with the remains of the wartime regimes and begin building institutions to oversee a process of constitutional evolution, aimed at creating a functioning state that is viewed as legitimate by the Bosnian public.

ESI analysis papers on southeastern Europe can be found on the Internet at: www.esiweb.org.

No peace without justice

After an inauspicious beginning, the International War Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (the Tribunal) has come a long way. Increasingly, the institution is viewed both inside and outside the former Yugoslavia as critical to restoring stability to the region and rebuilding trust between communities. Moreover, as more and higher-profile individuals are tried, it is building up a body of case law, which will be key to the future laws of war.

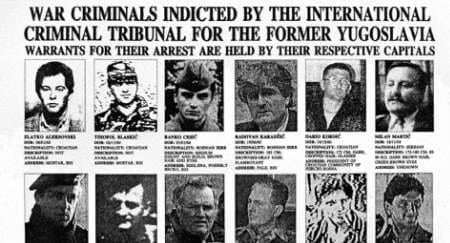

Founded by UN Security Council resolution 827 of May 1993, the Tribunal is mandated to prosecute and try persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, violations of the laws or customs of war, genocide and crimes against humanity committed on the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991. As of November 2000, 39 indictees were either on trial or awaiting trial, or had already been tried and found guilty. A further 25 war crimes suspects, including Radovan Karadzic, Ratko Mladic and Slobodan Milosevic, remained at liberty.

In its early years, the Tribunal faced a series of seemingly insurmountable problems. These included limited funding, hostility of local authorities, a shortage of suspects in custody, and luke-warm support among key members of the international community. Indeed, a year after the end of the Bosnian War, Tribunal representatives were not invited to the December 1996 London meeting of the Peace Implementation Council, the inter-governmental authority that oversees the peace process. Despite lacking a formal invitation, then prosecutor, South African Richard Goldstone, decided to attend this meeting, at which the first 12 months of peace implementation were reviewed. Soon after, his perseverance and that of other Tribunal officials began to yield results.

The Tribunals fortunes changed on 10 July 1997, when during a daring operation, UK peacekeepers arrested one war crimes suspect, Milan Kovacevic, and killed another, Simo Drljaca. Kovacevic and, in particular, Drljaca, were both big fish and their removal broke the cycle of impunity which had characterised the wars of Yugoslav dissolution. The feared backlash failed to materialise and more arrests followed in due course. To date, peacekeepers in the Stabilisation Force have arrested 19 indictees; three more war crimes suspects were either killed resisting arrest or committed suicide rather than surrender.

Even before 10 July 1997, several indictees were already in custody in the Tribunal. These individuals had either been arrested abroad, had surrendered voluntarily or, in one instance in June 1997, had been arrested in the jurisdiction of the UN Transitional Administration of Eastern Slavonia in Croatia. The first war crimes trial was that of Dusko Tadic, a Bosnian Serb, who had been arrested in February 1994 in Munich, Germany. After a 79-day trial and appeal, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison. Eight indictees have died; two while in custody. Charges against 18 indictees, three of whom were in custody, have been dropped. Two indictees were acquitted after trial.

Many in the international community feared that the issue of war crimes and justice would complicate peace negotiations and come in the way of a lasting settlement. The Tribunal was established following publication of a 3,300 page report by a commission of five legal experts under Cherif Bassiouni, a law professor from Chicagos De Paul University, examining reports of ethnic cleansing. The commission was set up in the wake of the London Conference of August 1992, organised in response to media revelations of the existence of Serb-run detention camps. The work of the Bassiouni Commission was largely financed by donations from the Soros Foundation, the charitable trust set up by international financier and philanthropist, George Soros.

The Dutch government gave the Tribunal a headquarters in The Hague, which is no longer large enough to house todays staff of 1,200. The Tribunals budget, which has grown from $276,000 in 1993 to close to $100 million in 2000, is paid for by the United Nations. Some activities such as the exhumations programme for Srebrenica, scene of the largest, single massacre of the Bosnian War, and an outreach campaign, explaining the work of the Tribunal within the region are externally funded. In addition, in the wake of the Kosovo campaign, 11 countries sent forensic teams to assist the Tribunal in its investigations.