Chris Donnelly examines the difficulties all European militaries face to meet the challenge of the 21st century, focusing on the armies of central and eastern Europe, where the need for reform is most urgent.

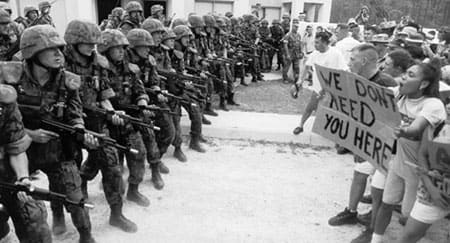

Troubled times: Todays soldiers must train for a wide range of stressful situations. (NATO photo - 29Kb)

Most European countries face a similar security dilemma. The forces they have and which they maintain at considerable cost are not suitable to meet many of the threats that Europe faces today and is likely to face for the foreseeable future. This is a dilemma for both NATO members and Partner countries, which therefore have an interest in resolving it together.

Kosovo has brought the issue to a head. Although Europe has more than two million soldiers and fewer than two per cent of them are deployed in the Balkans, the peacekeeping operations have placed an enormous strain on national military systems. Despite high defence spending, Europe lacks certain basic military capabilities and cannot effectively deploy forces out of area without US support. Something is clearly wrong.

Media analysis of Europes security deficiencies has focused almost exclusively on the need to buy high-tech equipment to match US capabilities, or on the need for European intelligence gathering, a corps headquarters, improved command, control and communications, and large transport aircraft. But the situation is more complex. To understand the military requirements of the 21st century, it is important to examine the nature of the threat in Europe, and ways in which that threat can be met.

Though the possibility of a regional war remains, as in the Balkans, mass invasion and total war have ceased to be a threat to East or West. Instead, most threats to national security in Europe today are non-military. They may evolve out of economic problems, ethnic hostility, or insecure and inefficient borders, which allow illegal migration and smuggling. Or they may be related to organised crime and corruption, both of which have an international dimension and undermine the healthy development of democracy and the market economy. Moreover, the proliferation of military or dual technology, including weapons of mass destruction chemical and biological as well as nuclear and their means of delivery, and the revolution in information technology present special challenges.

Whereas ten years ago, national security was chiefly measured in military might, today that is only one of several units of measurement and, for most countries, one of the least immediate. Most of the above threats call not for a traditional military response but require investment in interior ministries, border and customs forces, and crisis management facilities. But as investment in internal security increases, the pressure on defence budgets becomes even greater. It can in some cases, therefore, be counter-productive to urge countries to spend more on soldiers, if what they really need is police, both for their own security and to contribute to international security operations.

Experience demonstrates that when soldiers are called on to meet a security challenge nowadays they have to be able to do more than merely fight. The peacekeeping operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo have shown that, in addition to the ability to fight, soldiers require a range of skills to fulfil a wide spectrum of stressful and demanding roles, from diplomat through policeman and arbitrator to first-aid worker, hospital manager and city administrator.

Two more points can be added. The first is that todays soldiers are likely to have to operate outside their home countries. The second is that new chal-lenges are likely to arise which are today unforeseen. Tomorrows armies will therefore require a much broader range of competence than their predecessors. Soldiers will have to be more flexible, better trained and better educated, and forces will have to be capable of rapid, decisive, and sustained deployment abroad. This requires changes in security thinking and it implies changes in overall security investment.

Changes in thinking are already underway. The realisation of the need to deploy European forces beyond the borders that they are committed to defend, without excessive dependence on US support, has spurred the development of the European Security and Defence Identity. This programme, which seeks to improve European military capabilities, is not just an issue of new equipment, new command, control and communication structures or logistics mechanisms. It is also a question of the skills and abilities of the soldiers, sailors and airmen themselves.

Examination of the state of Europes armed and security forces reveals a mismatch. At the end of the Cold War, most European countries had relatively large conscription-based armed forces designed to defend national territory. Neutral countries, such as Finland and Switzerland, had to maintain large force structures capable of independent operation to make their defence credible. NATO members, secure under the US nuclear umbrella, could afford to spend less and maintain smaller armies, and still have credible defence. Nevertheless, despite a growing tendency towards military and industrial integration and multinational military structures, each NATO member has largely maintained its own national chains of command, national procurement systems and balanced forces organised on national lines. This has meant that there has never been the economy of scale possible in a large national system, such as the United States, or in a system with a fully integrated and standardised structure, such as that which the Soviet Union enforced upon the Warsaw Pact.

In the past decade, most European countries have reduced their budgets and force structures considerably. But many have yet to change fundamentally their structure. Instead of large conscript armies for national defence, they now have smaller conscript armies. Moreover, for a combination of political and financial reasons, these armies have reduced capabilities. Conscription periods have been shortened. Equipment has not been upgraded. Munitions stocks have been allowed to fall. Training has been cut back. The armed forces of NATOs European members have become dependent on US force-multiplier technology.

Since the probability of conflict was deemed low, and deterrence depended on a visible political and military stance, it was more important for NATOs European members to maintain a show of military power, than to develop real combat performance. This resulted in procurement policies that emphasised force structure rather than capability. For example, it was more important to buy an aircraft than the systems that would make it effective. Rapid technological developments plus institutional pressures reinforced the logic of this process.

Three issues have, in particular, affected the countries of central and eastern Europe since 1990. Firstly, they have retained an excessively large administrative, command and military education structure, eating up a disproportionately large share of the defence budget. Secondly, these countries have lacked an effective, modern and transparent personnel system, retaining instead a version of what they had in Warsaw Pact times. This constitutes probably the single greatest institutional obstacle to reform as, without such a system, there is no mechanism for evaluating, rewarding, promoting or posting to key jobs those qualified to drive change and implement new plans.

Thirdly, these countries suffer from a lack of national governmental capacity for defence policy formulation, defence planning, and crisis management. This is because, as members of the Warsaw Pact or constituent elements of the Soviet Union, they were unable to develop national control over their armed forces. Such expertise takes many years to develop. Most countries in central and eastern Europe therefore need a fundamental change in their military cultures, if they are to build forces suitable for fulfilling the kind of tasks which, as Kosovo demonstrates, European security is likely to require in the next decade.

Many of the new military functions do not require classical soldiering skills, but could be better done by police. In some circumstances, therefore, a gendarmerie might be more appropriate than an army. Certainly, in Kosovo today the shortage is of this kind of police. When more soldiers are needed, it is communications and engineering troops or psychological operations officers, rather than infantry or artillery. Soldiers will always be needed, but not all those needed in such operations will be soldiers. It is clearly best to avoid overloading soldiers with civilian functions. Yet it is also clear that these functions and structures have to be ready for almost simultaneous deployment with the military in peacekeeping operations.

Many analysts, especially in the United Kingdom and the United States, believe that a professional army is the solution to the security demands of the 21st century. This may be true for large, rich countries, particularly if they are separated from any possible enemy by water. But for small countries, and particularly for poorer countries, this poses serious problems of cost. This in turn means that countries capable of fielding large conscript armies might only be able to afford very small, well-equipped regular forces. Three factors contribute to the very high cost of regular forces, namely personnel, equipment and sustainability.

Personnel: Conscript soldiers are relatively cheap. They endure a low standard of living and need little by way of support, being unaccompanied by a wife or children. Moreover, they are always available for service, since they get little leave. Regular soldiers, by contrast, must be paid at competitive rates, provided with adequate housing and associated infrastructure for their families, lest they leave the army for better conditions elsewhere. Regular soldiers require reasonable leave periods and will be detached for training courses and the like during ser-vice, which will reduce availability.

The experience of the United States and the United Kingdom, which both have professional armies, shows a high turnover of regular soldiers. Moreover, most regular professional militaries employ individual rotation and replacement, that is, deploying soldiers on an individual basis. This is disruptive since personnel turnover is continuous and often exceeds 50 per cent per year. It also reduces small-unit cohesion and therefore compromises readiness. It is difficult to form units for an extended operation from personnel all of whom must have over nine months left before reassignment. By comparison many conscription-based militaries use unit rotation and replacement. This generates inter-changeable cohesive teams, platoons and companies. And it increases small-unit cohesion, resulting in relatively high readiness, once units are formed and trained.

Conscripts can therefore be good soldiers, if well trained and instructed. But while it is relatively easy to drill specific skills into conscripts, it is more difficult to train them to deal with a variety of situations, requiring a wide range of skills with the result that they are rarely versatile. Reservists, on the other hand, can bring support skills from civilian life. Their biggest shortcoming is maintaining combat skills. Afurther problem arises if force structures are reduced but remain conscript-based. Either the conscription term must be reduced or conscription must become selective. The former reduces effectiveness; the latter is socially divisive. The time is ripe to seek an alternative form of service, blending the advantages of both.

Equipment: For the past 30 years, as weapons and equipment have improved, their cost has risen much faster than inflation. Consequently, as forces modernise, if they retain the same size of force structure, the cost of equipment procurement as a percentage of the overall budget will double in real terms approximately every 18 years. If the percentage of GDP allocated to defence is constant, and if GDP does not grow annually in real terms by a considerable amount, then the costs of procurement will lead inevitably to a reduction in the size of the force structure. It is this, more than anything, which drives countries to conduct defence reviews. The politician who promises that leaner will be meaner and smaller equals better is in fact making virtue out of necessity.

Sustainability: To sustain modern armies on operations, experience shows that land forces require at least three times the manpower of the actual battalions making up the force structure deployed. Deploying 60,000 troops will, therefore, require a total operational force of some 200,000. In addition, an equal number is needed to staff the infrastructure to support the whole. Creating a modern regular army, therefore, requires at least five or six people for every one deployed in the field.

As forces need to become more flexible, versatile, and capable of being sustained abroad, their cost will increase and the size of force that can be afforded will decline. Indeed, the cost of maintaining such forces, which are likely to have to be used either for peacekeeping or regional wars, may prove greater than the cost of maintaining conscript forces during the Cold War.

It is possible to save money by careful defence spending. Countries often incur extra cost for political reasons, building their own aircraft instead of buying a cheaper foreign one, for example. However, the scope for such saving is limited. In the end, modern armies are expensive, and regular armies are much more expensive than conscript ones. All this presents the smaller countries of Europe with a particularly acute problem. If cost forces their armies to be reduced, they will rapidly reach a point when they cannot maintain high-tech forces because of the disproportionate cost on a small scale. They will likewise not be able to maintain balanced armies capable of all the functions required of a national defence force. The smaller the national force, the greater the proportion of the budget taken by the defence ministry and headquarter infrastructure.

Unwittingly, the desire of some countries to join NATO is adding to this problem. The demands of providing competent forces to NATO-led operations such as Kosovo push a nation towards developing small competent forces. However, these forces are so expensive that, to afford them, the country may have to switch scarce resources away from a force structure geared for national defence. The preparations for joining NATO may therefore reduce a countrys independent defence capability. In the absence of any guarantee of eventual membership, such a policy inevitably represents a gamble.

Some analysts argue that the armies of central and eastern Europe need a strong, reliable and competent cadre of non-commissioned officers (NCOs). In prac-tice, however, this is not easy to create. Armies reflect the social structure of their societies. France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, for example, have a strong tradition of middle management the factory foreman, the independent farmer, the shop manager, the small businessman. In civilian life these people have the independence, initiative and education to accept responsibility, which is carried into military service. Since this section of society is weak in central and eastern Europe because of the communist heritage, the material for the Western-style NCO is not necessarily available.

Over time, it should, nevertheless, be possible to develop this section of command. After all, both the British and German armies today base their NCO structure on training and education within the armed forces themselves. But this will have to be accompanied by a cultural evolution, so that the command structure is prepared to delegate authority down to the NCO level. Agood example to study here would be the Bundeswehr redefinition of East German Army officers posts as senior NCO posts.

The way in which governments assess the forces they need to meet the risks they face is problematic in central and eastern Europe since, in the communist system, such assessments were beyond their remit. Key decisions were usually taken in Moscow and relayed by the Party with the result that governmental expertise in this area was minimal. Moreover, even in the Soviet Union, civilians had so little knowledge of military matters that in effect the military decided everything. There was no real civilian governmental control of defence policy, and no civilian governmental capability in defence planning.

The consequences can be seen today in Russias new National Security Concept. This is a list of all possible threats prepared by each ministry or agency linked with security issues. It is a collegiate review of facts, but there is no prioritisation and no analysis of risk versus probability, with the result that it is of little use as a policy-planning document. Producing the kind of analysis necessary to make informed decisions requires an information system, which can draw on the widest possible range of sources, both open and secret. Western intelligence services do this well. But in many central and eastern European countries, the intelligence services still reflect the heritage of closed societies. Open information, a system to evaluate it, and politicians and civil servants educated to understand it, are essential today to enable intelligence to be used properly. It is not clear how long it will take many of the new democracies to develop this particular attribute of modern society.

The problems of defence reform for all European countries today are both great and urgent. For the countries of central and eastern Europe, with a Warsaw Pact or Soviet heritage, they are extreme, and the smaller the country, the more difficult they are to resolve. Indeed, so acute is the problem that the need to address more attention to it must be recognised at once.

Although there are no ready answers, the way forward will likely require increased transparency in defence planning and a joint approach. For most countries, difficult decisions will have to be made and issues which have to date been taboo, such as role specialisation for smaller countries that is dividing military tasks between countries will have to be considered. A partial solution might be regionalisation, with several countries pooling their militaries and each specialising in particular areas. The Benelux example could serve as a precedent. Whatever the strategies, the idea of security through alliance is the only sensible approach and all international institutions with a stake in these issues, NATO, the European Union and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, have an interest in collaboration.