The Alliance faces significant challenges from disruptive technologies and innovations in both conventional and hybrid methods of war. Distinguishing between uncertainty and risk can help to better prepare for emerging threats and to direct innovative initiatives to counter them.

The past several decades have seen the introduction of a number of disruptive technologies into warfare, including some whose effects are so extensive that they can be considered their own domains, such as cyber- and cognitive warfare. Meanwhile, new technologies continue to emerge, ones which, as a recent article in NATO Review notes, “are already beginning to turn speculative fiction into reality.”

For over 70 years, NATO has stayed at the forefront of technology to ensure the defence of its Allies and the success of its operations

NATO has long recognised innovation as an essential component of success in defence and deterrence. The accelerating pace of technological innovation, the manifold sources from which these innovations arise, and their effects upon our geopolitical reality represent challenges and uncertainty for the Alliance.

The past several decades have seen the introduction of a number of disruptive technologies into warfare, including some whose effects are so extensive that they can be considered their own domains, such as cyber and cognitive warfare. In cyber warfare, simulation software can mean the difference between victory and defeat. © Information Age

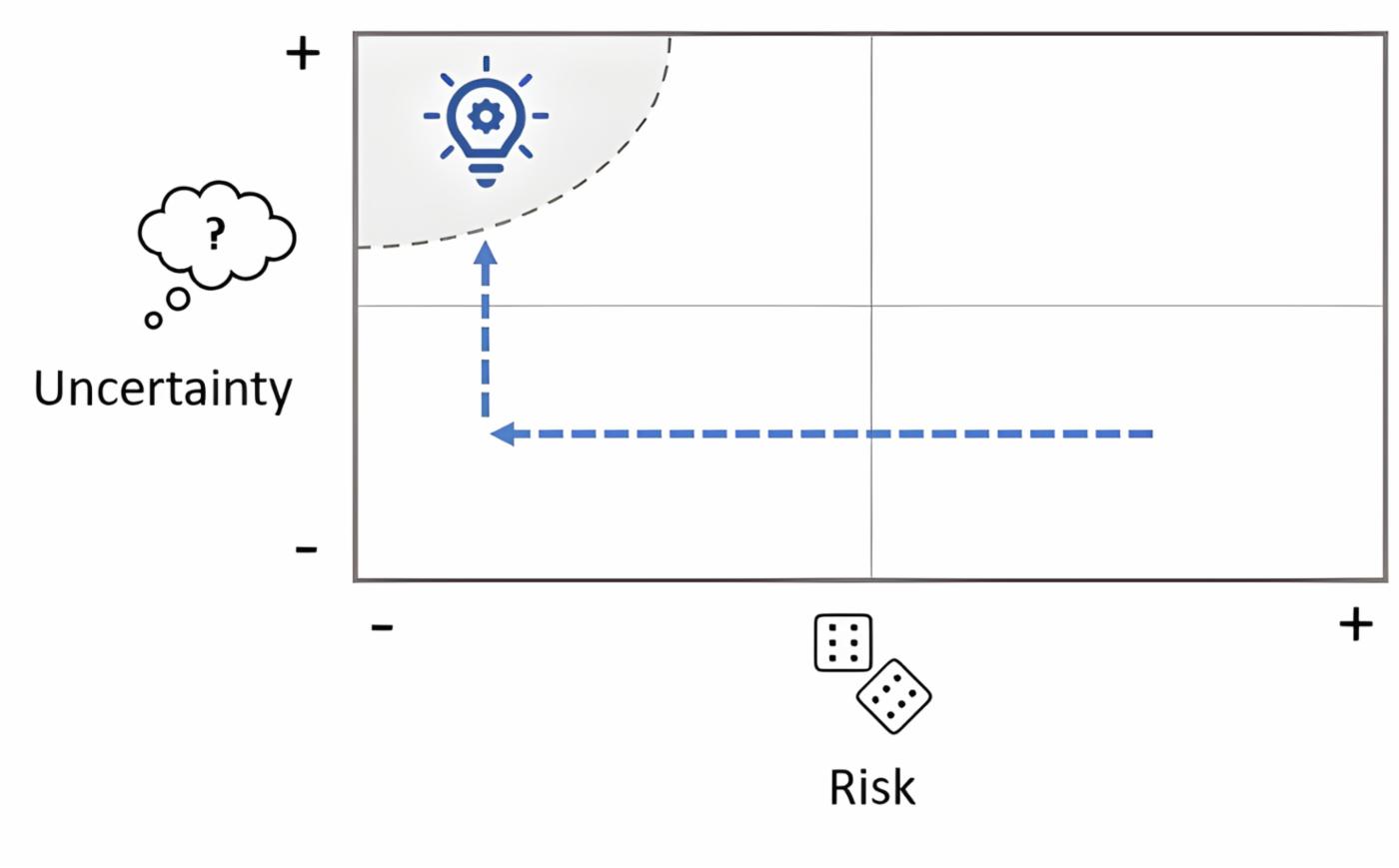

But this uncertainty, while a cause for concern, can also be harnessed to great advantage. The key is to make a clear distinction between uncertainty and risk, and to explore how both of these—risk and uncertainty—can be used in order to better prepare for emerging challenges, identify opportunities, and direct innovation initiatives.

Uncertainty is not risk

While some view the two as essentially the same and use the words interchangeably, uncertainty is quite distinct from risk, both in its character and in its use. In fact, what sets highly successful entrepreneurs and innovators apart from the rest of the population is the ability to see and use this difference as the basis for their success. The good news is that we can learn from them.

Risk is the probability of loss, injury, or other adverse outcome. It can be estimated and calculated based on our knowledge of prior outcomes and conditions. It has been mathematically formulated since the late 17th century, notably in the work of Blaise Pascal. Most importantly, it can be managed. Risk can be distributed (syndicated), insured against, hedged, and reduced. In short, it can be quantified and controlled.

Uncertainty is different. It is not subject to exact quantification. It was only recently formalised in the early 20th century work of the economist Frank Knight. It represents all of the possible future states of the world at any given time. The higher the uncertainty, the greater the number of possible outcomes, both positive and negative. It is a source of discomfort because we cannot predict it, but it is also a source of potential value. Higher uncertainty means greater potential, and most of us underestimate the extent of that potential since there are more possible future states of the world than we can possibly comprehend.

Entrepreneurs and innovators see value in uncertainty since they earn profits when gains are appreciably greater than is generally expected.

The innovation ‘sweet spot’: high uncertainty and low risk

If higher uncertainty is potentially good, how then do we benefit from it? The answer is to reduce risk as much as possible while exploring uncertainty as much as possible (see the diagram, below), to venture into spaces that might hold great potential while limiting one’s possible losses while doing so. Experienced entrepreneurs do this instinctively; they create low cost “minimum viable products” to test the viability of markets and technologies, thereby lowering their risk as they explore the uncertainty inherent in the market. They “sell” proposed offerings to customers before going to the trouble of making them. If only one of the entrepreneur’s many explorations pays off, then the gains can vastly exceed the small investments made to discover them.

High Uncertainty and Low Risk: The ‘Sweet Spot’ for Innovation

The essential point is that risk must be managed while uncertainty is explored, tested, and validated. This requires the entrepreneur to be both a risk minimiser (not a “risk-taker” as is commonly assumed) and an “uncertainty-taker” at the same time.

An example in action: hybrid warfare

Although recent events show the modern dangers of conventional warfare, innovations in hybrid war are unlikely to abate and may be further integrated into the full threat spectrum. Like the entrepreneur, the practitioner of hybrid warfare focuses on high uncertainty and low risk actions. In hybrid war, outcomes can be good or bad, but since they are novel or previously untried, no one can predict either way (i.e., probabilities cannot easily be assigned based on historical experience). If things go well, the result can be highly favourable for the aggressor. If they do not, they are survivable for the aggressor so long as they were taken at low risk.

Those who engage in hybrid warfare therefore work scrupulously to reduce their risk by ensuring deniability (e.g., via non-state or quasi non-state actors); by the commitment of small units or expendable resources (e.g., specialised units); by the use of low-cost technical means (e.g., drones, cyber); by the deployment of covert or hard-to-discover actions (e.g., infiltration, cognitive warfare campaigns); and similar means. These are employed with an attitude akin to a favourable coin toss: “Heads I win, tails I don’t lose much.” Such innovative methods also have an advantage over established competitors who may not anticipate them.

One counter-approach to unconventional methods is to create conditions that are the opposite of the high uncertainty, low risk position that is beneficial to adversaries. Responses to hybrid campaigns should focus on increasing risk for adversaries by making their moves predictably more costly, while reducing their ability to exploit uncertainty by proactively reducing their options. In other words, by frustrating their use of the innovation “sweet spot.”

Implications for NATO’s innovation

NATO and members of the Alliance know how to manage the risks inherent in developing large defense platforms and programs; ministers of defense and defense contractors are quite good at it. What the Alliance needs now is to learn how to better explore uncertainty, which is a different discipline.

NATO needs to work within the innovation ecosystem to encourage experimentation and investment in uncertain spaces. It needs to encourage a willingness to fail, to deal in ambiguity (as opposed to probabilities), and to make investments where the payoff is completely unknown (and may never come) in the hope of getting outsized results from some of its initiatives. Such encouragement does not attempt to modify institutional risk aversion. It is not risk-taking but “uncertainty-taking” that is needed.

Go ahead and make mistakes. Make all you can. Because that's where you will find success – on the far side of failure.”

Certain examples from industry may prove instructive. 3M, a manufacturer of over 60,000 products in several industry sectors, actively encourages employees to make mistakes. It invites employees to devote about 15% of their time to what it calls “experimental doodling.” 3M's business model succeeds by inventing entirely new, market-changing offerings. Unpredictability and failure sometimes lead to pioneering innovations. Reportedly, Google applies a similar strategy by encouraging employees to spend 20% of their time on projects that show no immediate promise but could benefit the company in the future. The policy produced Gmail, AdSense, and Google News. The multinational IBM is also known for fostering such a culture.

Going beyond the predictable

At present, NATO innovation efforts have concentrated on seven areas of emerging and potentially disruptive technologies, including data, artificial intelligence, autonomy, space, hypersonics, quantum, and biotechnology. While these are likely to be important in the future (since most are already important at present), it would be wise to extend the exploration into additional areas of uncertainty.

The objective of NATO innovation should be to encourage the triple helix of government, industry, and academia to engage in explorations of uncertain technologies that go far beyond those currently envisioned. The Alliance should strive to create a broad portfolio of innovation areas, some of which may currently be considered more akin to science fiction than science fact, and explore technologies where the uncertainty is so great that opportunities can scarcely be imagined, and research is therefore more difficult to encourage and to sponsor.

At present, NATO innovation efforts have concentrated on seven areas of emerging and potentially disruptive technologies, including data, artificial intelligence, autonomy, space, hypersonics, quantum, and biotechnology. Pictured: The Air Force’s AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon. © National Defense Magazine

NATO is doing some of this already. Its Allied Command Transformation, Innovation Hub, and Innovation Office engage academic institutions and private ventures in pushing the bounds of what is possible. The Innovation Fund and the Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) are other notable examples. But these efforts will only be successful if they are given the freedom to explore, and at times, to fail. According to Rob Murray, Head of NATO’s Innovation Unit, the Alliance should encourage “all elements of the innovation ecosystem to explore uncertainty and to genuinely drive forward innovation, even if that means making some mistakes. This will require a freedom to operate that is rarely exercised in the public sector.”

Risk and uncertainty are different. By more fervently exploring uncertainty while simultaneously reducing risk, the Alliance can place more bets on a wider range of opportunities than at present. Its aim should be to discover the unexpected, and to do so while maintaining the ability to “surge” resources into those areas that prove to be most relevant and impactful in the uncertain future.